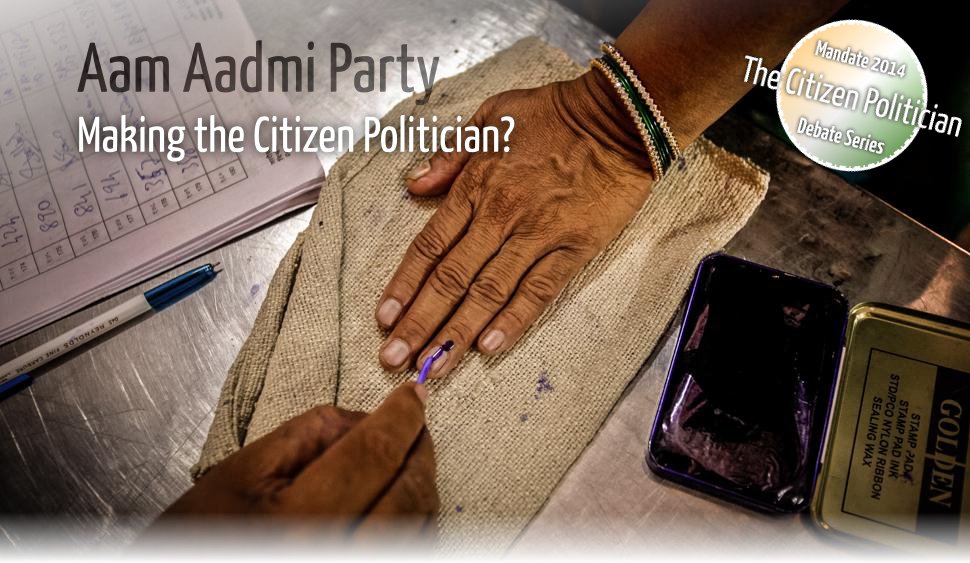

24 February 201449 days. The AAP ministry in Delhi lasted less than two months, and curiously, its closure, owing to the resistance to the implementation of the Jan Lokpal Bill, echoed the wave of commitments at its inception. Today, supporters as well as critics agree on this: AAP has been an unprecedented political exploration. The AAP government deployed unusual methods and strategies for a major party. What are the lessons of the AAP rule in Delhi? Where did AAP pioneer? And where did it fail? What was its political or ideological faux pas? Sarah Joseph returns to the events of the last two months, observes the appropriation of the AAP rhetoric by the two main national parties, and looks forward to the continued efforts of the movement, particularly in the parliament to come. In his response, Rajgopal Saikumar assesses the actual effects of the party, beyond its rhetoric, and returns to Martin Luther King to re-posit political tension as the main gain of the AAP rule. |

Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations and descriptions.

A Different DreamSarah Joseph |

The Need for Political TensionRajgopal Saikumar |

|

Those who rejected the Jan Lokpal Bill ended up rejecting, virtually, the aspiration of the common people from all walks of life. This aspiration will definitely be reflected in the coming Lok Sabha elections. AAP will be a significant force in the parliamentary elections. Even if AAP does not get the necessary majority, they will be standing for the people who question the corrupt, the dynastic rule and the communal forces. Even with five MPs, AAP will give a sleepless time to the current crop of politicians, in the parliament. The original aim of AAP is to return the power to the people. This process is only possible if the Jan Lokpal Bill is passed and if people get a say in a truly democratic process.

Whoever aims at making the necessary changes in a system that is already rotten – be it AAP or any other neo-political undertaking – needs to make path-breaking systemic changes. And such pioneering, reformative ways of functioning may be branded as excessive by the conventional political forces. One cannot make changes in a non-functioning system simply by singing lullabies to it… The need of the hour is to wake up, to imagine in a new way, to dream differently. That is where the experience of AAP becomes relevant and important. Existing political parties have lost the ability to make the people dream and function differently. So, when Kejriwal asserts that he and AAP will only stand with the aspirations of the people, rather than being rhetorical, it is the signal for authentic, new change.

What did we learn from the 49 days of AAP ruling in Delhi? In a true democracy, the power should be in the hands of people. Thanks to AAP, this notion has become stronger in the aspiration of people in India. Once elected, our ministers, MPs and MLAs have more affinity with the corporate than the common people of this country. And this is borne out by the way these parties have united to attack the vision of AAP. By doing this, they have exposed their true affiliations. But ironically, due to the bankruptcy of their own visions, they are trying to make the ideas of AAP as their own. Here, Rahul Gandhi forces his own minister to give twelve cylinders to the common people, supports 50 per cent reservation for women in seat allocations, declares that he is not part of a corrupt party and reminds us of the need to fight against communal forces. And there, Narendra Modi shouts for a corrupt-free India. But all the while, behind them stands the gigantic power of Mukesh Ambani… These two wannabe idealists and their parties shake each other’s hands and defeat a bill that was meant to be the preventive tool of corruption, the enabler of true democracy. People are now aware of an alternative way of functioning. And they have hope that the AAP will give directions for this alternative.

Indian politics will not be the same anymore. AAP itself is and will be the new era in Indian politics. The main political parties have forfeited the trust of the people in this country. Now, the seeds of righteousness have been sown into the heart of the people and the effect of this will be reflected in the coming Lok Sabha elections. Already, the policies of AAP have compelled the mainstream political parties to course-correct their functionings. This is a welcome change! To achieve a complete Swaraj, if these parties change, then AAP’s coming to power is not necessary. AAP’s function is to catalyze change. Whether it does this from within government or from outside it, does not matter. ‘Pick up the broom and work hard for the people!’ is AAP’s clarion call for change. Major political fights are ahead of us. The primary concern of this party is to make the Jan Lokpal Bill a reality. This bill becomes the most important tool in the fight against corruption. It needs to become a law. So when the AAP government gets shunted out of power rather than dying on its own, the need does not get shunted out with it. The movement for a Lokpal Bill started years ago and this relentless work forced the Congress government to introduce diluted versions of the bill many times. But the inadequacy of this bill is what created a movement for a stronger law and this movement became the AAP at some point. The resignation of Arvind Kejriwal has brought a sharper focus to the passing of this bill.

Finally, AAP’s fundamental aim is to give power to the people through decentralization. From the start, AAP has been doing just this. People hope that in the near future, Indian history will witness the passing of the Jan Lokpal Bill. And this will provide a model for democratic practice not only in the country, but all over the world. |

The AAP dream about the emergence of true democracy is not strengthened by any methodological intervention. For instance, how does one link passing of an anti-corruption bill with returning power to the people? These claims are so deeply riddled with argumentative leaps that it becomes hard to find their cohesion in the implicational scheme of governance. They seem to be a furious spurting of punch lines and USPs. Nothing is said about how exactly this power will be given to the people, or how the ‘ideal AAP’ decentralization will occur within the current constitutional framework. Are we here talking about a shift from representative democracy to participatory democracy? If the movement of the discourse is towards the institution of ‘mohalla sabhas’ and referendum systems as suggested by AAP, then one must respond that its technical viability and constitutional validity are highly questionable. How does one ensure the protection of minority rights and accountability within the ‘mobs of the mohallas,’ for example?

It is redundant and inadequate to say that what the AAP rule has given us is the definition of democracy as people’s power. On the other hand, AAP has reminded us of the significance of a fundamental phenomenon that sustains any political community: tension. It highlighted the role such tension plays in enabling a deliberative and participatory democracy. At the very least, AAP snapped a few urbanites out of their political nihilism and at the most, AAP augmented discussions, deliberations and wider civil society participation in Indian politics. One must trace the history of the use of ‘tension’ in politics back to Martin Luther King Jr. who stressed “dramatizing the issue” so as to force a confrontation: “Non-violent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and establish such creative tension, that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue” (“Letter from a Birmingham Jail”, 1963). After Gandhi, it was King Jr. who understood political tension as a ‘constructive non-violent tension’ that is necessary for growth. In the context of AAP politics, this tension has often been portrayed as anarchy and disorder. A commonly heard critique of AAP is that their means and methods are a threat to law, order and security, with a possibility of violence erupting out of such politics. Such comments suggest that governance is not about protests and disorder, but is a gradual technical process meant for the experts.

To an extent, it is a legitimate fear. A dharna before the Rail Bhavan can get out of hand, turn violent and destructive. But there is something more to this middle-class insecurity vis-à-vis any experimentation with radical politics and democratization. King jr. warns us against “the white moderate who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice”.

Negative peace is possible even in a military regime; there is ‘peace’, but this is far from non-violent peace. The middle class, the moderates, the upper castes – including those who are ‘for’ social transformations – the judges and legislators: everybody aims at this ‘negative peace’. They want transformation, but they hasten to add, ‘when the time comes, it will happen.’ As King Jr. observes, the moderate person “paternalistically feels that he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; …lives by the myth of time and … constantly advises… to wait until a ‘more convenient season’.” For King Jr., “lukewarm acceptance is more bewildering than outright rejection.” What AAP revealed to us is this dangerous façade of negative peace, a forced silencing of tension disguised in the language of order and security. There is a need to claim tension as a striving for a ‘positive peace’, for the construction of social justice. Most of what Sarah Joseph claims about AAP, falls beyond originality, and does not seem to be technically workable. As a manifesto, however, they are appealing mantras and slogans. In the current scenario, these claims are a part of larger branding campaigns in the competitive marketplace of politics. Indeed, what AAP has done in its 49 days is highlighting the importance of political tension in a democracy. Political tension creates participation, discussions, deliberations and a temporary consensus necessary for effective governance. It has brought home to the Indian citizen the need to actively engage and critically experiment with the political. |

|

Sarah Joseph is a novelist and short story writer from Kerala. Her 1999 novel Aalahayude Penmakkal (Daughters of God the Father) received the Kendra Sahitya Akademi Award as well as the Vayalar Award. The founder of the organisation Manushi, Sarah Joseph is one of India’s foremost feminist voices. She is a member of the Aam Aadmi Party.

|

Rajgopal Saikumar is a Research Associate at Centre for Law and Policy Research (CLPR), Bangalore. He has a degree in law and holds a M.A in Philosophy. Prior to his affiliation with CLPR, he was a Public Policy Fellow at The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, Chennai.

|

Disclaimers: The opinions expressed by the writers are their own. They do not represent their institutions’ view.

LILA Inter-actions will not be responsible for the views presented.

The images and the videos used are only intended to provide multiple perspectives on the fields under discussion.

Images courtesy: Aijaz Rahi | PTI for Hindustan Times | Tsering Topgyal | Mediabull | Anindito Mukherjee | The Orlando Scene

Share this debate… |

… follow LILA… |

||||

The Jan Lokpal Bill has been rejected, and Kejriwal fulfilled his promise: the AAP government resigned. The united shouting games played by both the Congress and the BJP, raising minor technical matters, against the passing of the bill in the Delhi assembly have exposed these parties to the people of India at large. Instead of initiating a genuine debate on the bill, the mockery created by these two giant national parties may have led to the resignation of Kejriwal’s government in Delhi, but it also created a huge awareness for the need of this law.

The Jan Lokpal Bill has been rejected, and Kejriwal fulfilled his promise: the AAP government resigned. The united shouting games played by both the Congress and the BJP, raising minor technical matters, against the passing of the bill in the Delhi assembly have exposed these parties to the people of India at large. Instead of initiating a genuine debate on the bill, the mockery created by these two giant national parties may have led to the resignation of Kejriwal’s government in Delhi, but it also created a huge awareness for the need of this law.

Sarah Joseph’s defence of the Aam Admi Party has a very perceptible propa-gandist tone. Her argu-ment reiterates some of the claims now widely circulated in the media. One notices that the performance of repeating them, almost liturgically, has given them a political force that is now becoming unquestioned. Her statement “the original aim of AAP is to return the power to the people. This process is only possible if the Jan Lokpal Bill is passed and if people get a say in a truly democratic process” leaves the reader rather puzzled. It is unclear what “returning power to the people” actually means in the modern Indian State, where democracy works within a certain design of representation through legislative, executive and judicial powers creating an inter-institutional equilibrium. What AAP has to tell us today, is how it proposes to bring about “true democracy,” and not merely claim it.

Sarah Joseph’s defence of the Aam Admi Party has a very perceptible propa-gandist tone. Her argu-ment reiterates some of the claims now widely circulated in the media. One notices that the performance of repeating them, almost liturgically, has given them a political force that is now becoming unquestioned. Her statement “the original aim of AAP is to return the power to the people. This process is only possible if the Jan Lokpal Bill is passed and if people get a say in a truly democratic process” leaves the reader rather puzzled. It is unclear what “returning power to the people” actually means in the modern Indian State, where democracy works within a certain design of representation through legislative, executive and judicial powers creating an inter-institutional equilibrium. What AAP has to tell us today, is how it proposes to bring about “true democracy,” and not merely claim it.