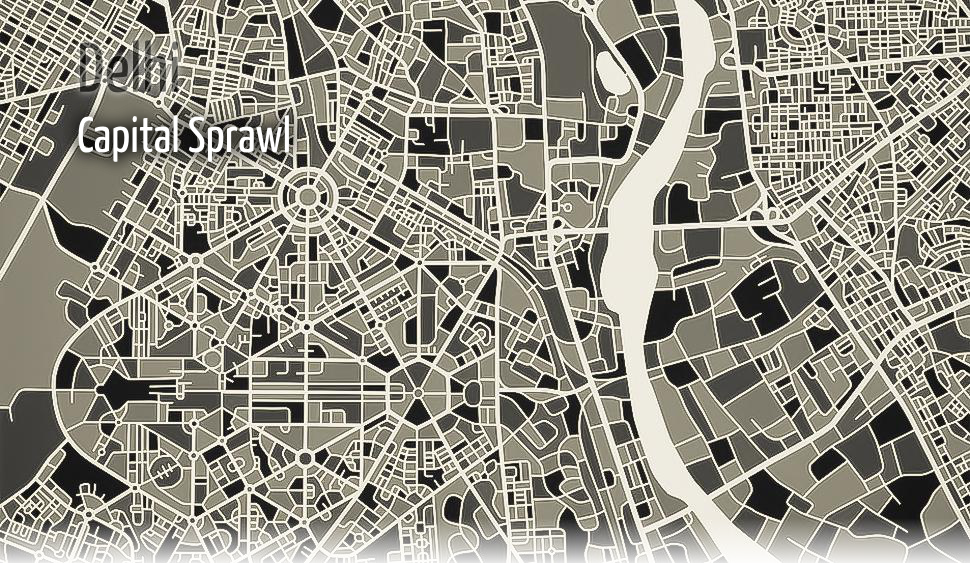

Capital cities are inherently distinctive because of the infrastructure required (buildings and public spaces) for the needs of governments and national events. Some of the most celebrated examples of capital cities are classical Rome with its forum, baths, and amphitheatre and, from the medieval and early modern period, London and Paris, where the court functioned from royal palaces and the public enjoyed the pageant of processions through the main streets. In these and other similar cities, improvements to the public realm took place regularly – for instance new temples and triumphal arches in Rome, and road widening in Paris and London. Purpose-built Secretariat buildings came comparatively late, only in the nineteenth century in London but, when they did, no expense was spared to reflect the grand purpose of these edifices.

Of those three European cities, Delhi is perhaps most akin to Rome, in that the city has waxed and waned in importance and, also like Rome, the modern city was built among the visible ruins of earlier states. However, unlike Rome and most other cities, the earlier urban developments were not built on top of each other, but some distance apart, leaving a convenient and large space, south of Shahjahanabad, the Mughal city, and north of the earlier sultanate cities, in which the new colonial capital was built. Awareness of this heritage informed the layout of New Delhi, in that some of the ancient remains were integrated into the plan, for instance the Lodi Gardens tombs and the Purana Qila, which was originally to have formed the backdrop to the view down Rajpath. However the example of London and diverse over-grown cities in nineteenth-century Europe and North America, with their appalling slums and social problems, was also influential and led to the deliberate attempt to create a capital at Delhi that would avoid such problems by reducing its role to a purely administrative function, leaving the mercantile business in the port cities of Calcutta, Madras, Bombay and Karachi, as they were then called. Of course, living conditions for the colonial population were similar everywhere, with airy bungalows set in large gardens as the norm, so the Delhi plan was merely following tradition, as if the new city was a vast Civil Lines with the addition of an awe-inspiring complex of governmental buildings.

This resulted in a New Delhi of magnificent government buildings and a fantastic processional way, combined with a suburban population density. In some respects, it is similar to its predecessor Washington DC, and recently created capital cities, such as Canberra, Australia (started in 1913), Brazilia (1960) and Abuja, Nigeria (1980s), which are all Federal Capitals of large diverse countries, but which all share a reputation for lacking the sparkle of their business-focused rivals New York, Sydney, Rio and Lagos.

The surroundings of Rajpath:

all in the design

Since Independence, new government buildings in Delhi have filled, along Rajpath, the spaces originally designated for them, often built in a fairly utilitarian style, appropriate to the new, supposedly egalitarian society of the new country. There has also been a certain amount of redevelopment of bungalow plots around Connaught Place. However, in much of the area, the use of the original buildings has hardly changed and the hierarchies of office and residential accommodation has stayed the same. The remaining bungalow areas are jealously guarded – not just by those few who directly benefit, but by a large population of conservationists who have a great affection for this leafy utopia, an affection surprisingly greater than for the buildings constructed at the same time by and for the local population.

The result of this is a hollow-centred city with areas of medium and occasionally high density surrounding the 26 km2 colonial city, now known as Lutyens Bungalow Zone (LBZ). Although pre-nineteenth century London or Paris would comfortably fit inside this area, by comparison with those particular cities very little takes place in the LBZ: government offices, a few cultural centres, some down-market office accommodation, and housing for government servants, with a few markets around the fringes. Nonetheless, there is no single rival nucleus, and the architecture of the administrative centre proclaims it as the seat of the Government.

When one considers the common features of successful modern cities, an important one is that the centres are the densest part, with a heterogeneous, close-packed mixture of buildings serving the needs of business, education, culture, religion, ordinary life and, in the streets, the layering of myriad overlapping activities, resulting in an animated street scene: people walking to work or school, shopping, chatting in the street, taking exercise. One of the crucial elements of this is the walking, which becomes a sensible option when combined with good public transport and obstacles put in the way of car use in the city centres.

Why is Delhi so far from matching this description? It does, of course, inside the old city of Shahjahanabad, where small scale businesses coexist with residences, but also with uncomfortable levels of overcrowding and poverty. Elsewhere, housing colonies function adequately as dormitory areas, with local markets and small open spaces, while businesses have been driven out of the city centre to Gurgaon or Noida. However, the scattering of business and residential areas to segregated zones on the periphery of the city creates a need for people to travel great distances. The rapidly expanding Metro system is responding to the high level of need but the demand is huge and only partially met, so far.

How to actualise the potentials of Lutyens’ Delhi?

The history of Delhi and the affection for the Lutyens Bungalow Zone means that the current morphology of the city is unlikely to change. However the question is whether individual bungalows, most of which are in public ownership, are currently being put to the best use. The problem for city planners, therefore, is to reconcile the urge to conserve the much-admired LBZ with the need to make better use of this hollow city centre, to make it a more vibrant and pedestrian friendly place. It is certainly difficult to imagine that much further encroachment, of the type that surrounds Connaught Place will be allowed. Perhaps the answer lies in altering the use of the bungalows so that there is pedestrian permeability through the blocks, with higher density development allowed at the rear of the sites, along the service lanes. The answer may also lie in new ways of working in the digital age, reducing the need for concentrations of offices, although this is not indicated in current city development. Whatever happens to the working environment, it is to be hoped that city centres will remain a focus for the concentration of cultural, recreational and educational facilities. An LBZ that combined all these activities by integrating the bungalows, via tree-canopied footpaths, with the modern infrastructure needed in a twenty-first century cultural capital would be a utopia indeed.

|

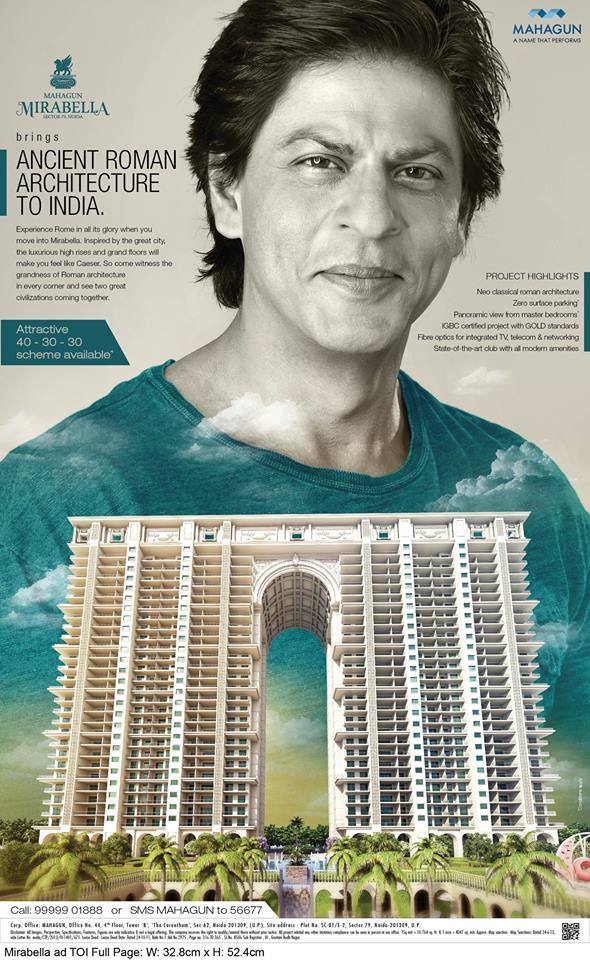

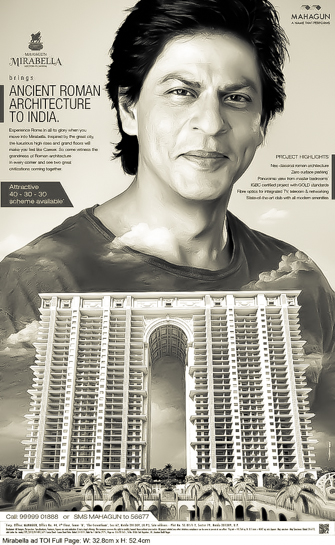

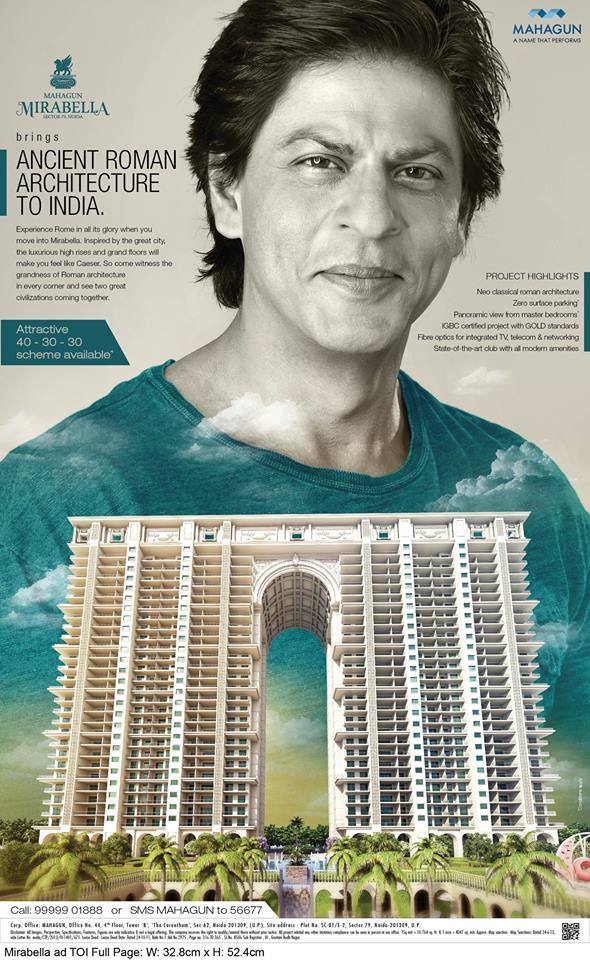

On 11 February 2015, the day after the results of the Delhi Assembly Elections were announced, a leading national daily had on its cover page the following two images. On the one hand, there was a mosaic of several ‘aam aadmi’ from many of Delhi’s not-so-upscale localities, celebrating the overwhelming victory of their party in the streets of the city. On the other, there was an image featuring a new high rise multi-storey upscale housing in Delhi designed to look like what can only be described as a combination of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris and the Arch of Titus in Rome. And if that was not bizarre enough, what the image also showed is that the sky, framing the building slowly morphed into a t-shirt out of which loomed, almost as large as the building itself, the smiling face of Shah Rukh Khan, the current king of the Hindi movie industry and the brand ambassador for the company promoting the building. Accompanying this image, which seemed to suggest that those living in this building would always be nestled with(in) the bosom of Khan, was a bold caption that read “…brings Ancient Roman Architecture to India.”

A confusion of references?

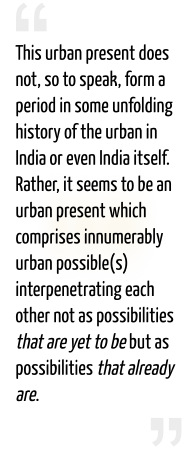

Exigencies of newspaper design and revenue collection aside, which, I am sure, must have had much to do with how these images lined up, their simultaneity is also not completely uninteresting. For me, it represents, what I shall call ‘urban present’ in India. What is unique about this urban present is that, much like the images themselves, it does not seem to be beholden to some overarching singular logic. It does not, so to speak, form a period in some unfolding history of the urban in India or even India itself. Rather, it seems to be an urban present which comprises innumerably urban possible(s) interpenetrating each other not as possibilities that are yet to be but as possibilities that already are. I can only present some outlines of these here.

There is, of course, the urban possible of Capital, of neo-liberality that already is. This is a possibility which leaps ahead, as it were, to continually gather every entity within it, transforming them, enveloping them. Within it, spatiality and temporality have, along with exchangeability, as their essential being, homogeneity, measurability and calculability. Thus, everything encountered within this urban possible is also seemingly rational, natural, and analogous, and devoid of particularity. This possibility animates expertise and technology to actualise these ends, transforming them too in the process. They begin to act as mediators and markers used by or on behalf of those who would govern. This techno-political urban possible is not simply about the merely material. It comprises the producing, managing and governing of health, of illness, of morality, of play, of attitude, of danger, of risk, and indeed of self and others. Its representational possibilities, quixotic, self-evident and specialised, are constantly hemmed in and constrained by the demands of a corporately framed agenda that is seeking to generate, maximise and increase the ambit of shareholder value.

The unauthorised colonies:

organic infants of the city

And yet, even as this is a possibility, other urban possibles also are. There is, as Ravi Sundaram recently pointed out, the pirate urban, a possibility of spawning non/paralegal inhabitations. Such ‘illicit’ inhabitations, he notes, are possibilities enabling significant resource for subaltern populations. Here, technology, while bringing these inhabitations within the purview of the neoliberal techno-political urban, is also mutating. It undergoes a process of cutting, editing, grafting… Each movement, he says, “is not more of the same, but a giant difference machine, each experimenting with possible openings in the city and becoming another.”

Urban communitarian formations too are transfiguring in their replicability. Thus, while techniques continue to create solidarities of fear, risk and danger, they are also possibilities of momentary and differential formations impinging upon one another, transforming one another. Indeed, subjectivity itself is (dis)continuing. As the anthropologist Nikolas Rose puts it, the biomedical technologies which are envisaging vitality today, “do not attempt to hybridise the body with mechanical equipment but to transform it at the organic level, to reshape vitality from the inside: in the process the human becomes, not less biological, but all the more biological.”

What, then, are we to make of this urban present of possibilities that already are, which I have inadequately sketched? To be honest, I do not know. And moreover, any answer to this question will necessarily have to ascribe to some kind of a singular, a ‘higher’ logic that will reconcile this urban present.

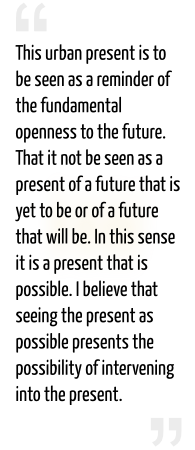

But what should be palpable from my account, however, are two things. The first being that the urban present I attempted at articulating is to be seen as a reminder of the fundamental openness to the future. That it not be seen as a present of a future that is yet to be or of a future that will be. In this sense it is a present that is possible. I believe that seeing the present as possible presents the possibility of intervening into the present.

Open to the tomorrows of Delhi?

The second follows from this. If there is to be an intervention into the present that is possible, then there has to be fundamental questioning of the technicality of the Master Plan, of design, of designers and such like. These, as I have argued elsewhere (“Architectonic Improvisations: Modernity and Design(s) in Postcolonial India,” in Modern Makeovers: The Oxford Handbook of Modernity in South Asia), orient their being by marginalising and expelling the present that is possible, thereby foreclosing right at the outset the fundamental mutability to the future. They speak, that is, of only present urban(s), not of urban present(s).

|