|

16 January 2015

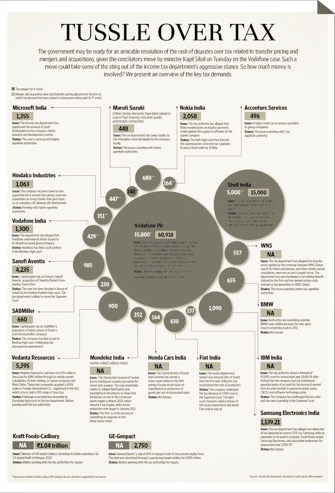

Behind the walls of our Sabhas, hidden somewhere between the shushes of our technocrats, a major turn of world history may be engaged. 2015 may be the first marks, almost imperceptible, of a new era, less than seven decades before the proclamation of the Indian Union. Long after its first mentions in 2000, the GST or Goods & Services Tax was finally introduced last month, and its specific elaboration is under discussion. GST, or the regime reform towards a sort of Value Added Tax applicable to all across the Union, aims at systematising fiscal matters by centralising deductions so far legislated by each State. But, if taxes, too, are of, by, and especially, for the people, what meaning shift would this reform imply? That the direct financial collective to which an individual owes her dues is her country, and not her state, region or tehsil? Today’s ideological battle seems to be between the expansion of homogenising and structurally stable centres on the one hand, and the weakening dreams of multiform yet thus adaptable peoples’ governance across pluralistic spaces. Right at the dawn of India’s entry on the podium of world geopolitics, we face the temptations of championing either of these two taxonomies, two routes more determinant than ever before. This week on LILA Inter-actions, Vinod Vyasulu finds in progressive taxation the actual regime reform urgently needed in India, along with a larger, in-depth rethinking of the meanings of the Federal. K Swaminathan examines the ethos and tenets of the GST bill, and rediscovers how the Government has been a reliable force to subtly bridge economy and culture.

Debate

Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations.

|

|

India has been considering tax reforms for a very long time. The first major report, in the 1950s, was prepared by Nicholas Kaldor, who recommended an expenditure tax. After much debate, India decided to adopt an income, not expenditure tax, in the law passed in 1960. Indirect taxes like sales tax were the domain of the States, and over time, each State has developed its own system. The total revenue is the combination of the two taxes.

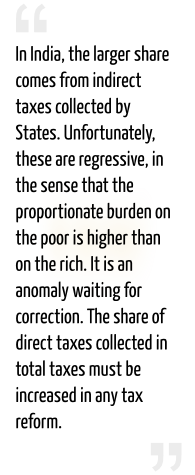

However, in India, the proportion of taxes to national income is small. This shows that revenues could be increased fairly easily, if international experience is anything to go by. Further, the share of direct to indirect taxes reflects the extent to which the tax system is progressive – that is, based on the ability to pay principle. In India, the larger share comes from indirect taxes collected by States. Unfortunately, these are regressive, in the sense that the proportionate burden on the poor is higher than on the rich. It is an anomaly waiting for correction. The share of direct taxes collected in total taxes must be increased in any tax reform.

The structure of the income tax is standard. Those who earn less than a specified amount are exempt from being taxed. This amount has been changing – generally moving upwards to keep pace with changes in society – and with inflation. There are certain items of saving or protection, like insurance and so on, which qualify for a tax exemption or rebate. This basket of exemptions has been changing from time to time. This is because these forms of saving are considered good to both the individual – she is forced to save for the future – and the country, as it contributes to national savings and enable public investments.

Once one reaches a taxable level, the system is progressive. Today, we have a tax rate of 10% for those with an income above the specified limit and up to 5 lakhs a year. The second slab, of 20%, is for incomes between 5 and 10 lakhs. All incomes above that are taxed at 30%, with those having a declared income of above 100 lakhs having to pay a surcharge. This has evolved over the years, and has settled at this low rate (low, by international comparison). This is because the government believes it is necessary to keep taxes low enough to encourage investments. But, given the requirements of the country, I believe there is a case for higher rates on those with large incomes. For example, those with incomes between 15 and 25 lakhs a year could pay 40%, and those with incomes above 25 lakhs, 50%. This should also apply to corporations. And myriad exemptions allowed to corporations should be eliminated.

A progressive taxation regime

would give less leeway to corporations

There used to be both wealth and estate taxes. While the wealth tax needs to be changed drastically, the estate tax was abolished many years ago. I argue that the time has come to introduce it again. Incomes have shot up, wealth has increased, and inequality in India has reached historic levels. It is hard to say by how much, because the All India Income Tax Statistics no longer publishes the details, as they did between 1922 and 2000. However, it can still be established that inequality has increased between 1980 and 2000. I suspect it has increased since 2000.

Equity demands that steps be taken to reduce such inequality. Exactly how this should be done, and what tax rates should be charged, should emerge from a public debate. But indeed, taxes are essential for reducing inequality. This extra revenue can be used for education and health, which should be provided by the Indian State to all citizens.

Capital gains, which are unearned income (rents), are treated favourably in India. The short-term rate is 10% and the long-term rate, 20%. I see no justification for this favourable treatment. All income classified today as capital gains, including agricultural income, should be treated as income, and taxed according to the slab the taxpayer is in. In addition, there is a case for a transactions tax, say of 0.01%, on all bank transactions, and this should be shared completely with the States.

India at Independence chose a federal structure in which the Union Government had certain responsibilities and States, others – particularly those related to health, agriculture, industry and so on. Direct taxes are collected by the Union and shared. Given our colonial past, the largest share of such income has remained with the Union Government, which does pass on some to the States as ‘plan transfers’.

It would be better if this was changed. The share of the Union should be reduced to meet its constitutional obligations – defence, foreign affairs, railways etc – and the larger share passed on to the States to use, according to their own priorities. Since the Planning Commission has been done away with, this should be easy to implement. What is called the ‘vertical transfer’ should be changed to favour States; for example, the Union could get 25%, and the balance would go to the States, taken together. This reduction in resources with the Union will compel it to become more efficient. One way of doing this would be to do away with the ministries whose subject belongs to the States in the Constitution, for example agriculture. This government has already shown its political will to do this by abolishing the erstwhile Planning Commission. So, this is eminently feasible.

With the Planning Commission stopped,

reactive fiscal attempts are possible

There are proposals about indirect taxes being replaced by a Goods and Services Tax (GST), as in Singapore. If this were introduced by forging an agreement with the States so that all could agree to a uniform rate, it would be a major step forward, as tax administration would become simpler, and businesses would find the going simpler. Estimates say this could add more than 1% to national income.

However, the process has got bogged down because the Union Government has chosen to amend the Constitution and take away the power of indirect taxes from the States, to replace it with a Union-managed GST. This would take away the one thing that characterises a Government: the power to tax. It would reduce the State Governments to mere agents of the Union, and go against what has been called the ‘basic structure of the Constitution’, which includes its federal character.

It is no wonder that the States have been reluctant to get on to the GST bandwagon. The talk about revenue loss and compensation is shadow boxing. The real issue is the federal nature of State Governments in India. Thus, a constitutional amendment is not necessary if the States, through negotiation, agree to a common rate which each State will then voluntarily adopt. This would leave open the possibility of cancelling the arrangement in the future. If it does result in greater revenue generation, there will be no incentive to do so. This way, a uniform GST structure could be implemented immediately. And that would be good for the country and the economy.

This is a time of flux. There are great opportunities for our political leaders. We have to see if they are up to it.

|

I wonder why there is so much hype and debate on the taxes and their economic impact on the people, while there is none on how they impact the nation. While this question may not be very relevant in other countries, this question is very pertinent in the Indian context. A unique feature of India as a nation is its inherent diversity – lingual, ethnic and cultural. This is probably attributable to its underlying philosophy: that the manifold expressions emerge from a single Source or Reality. A nation goes beyond a country – it refers to tightly-knit groups of people that share a common culture. Peoples, in any nation, undertake economic activities, earn money, and taxes admittedly impact their buying power. Thus, how taxes impact the common man is debated. But my question is: why is no one discussing how the common man’s economic activities, which admittedly is affected by taxes, affects him back, his cultural identity, and hence the nation. It may be worthwhile reflecting about where we began as an independent country, how we think as a nation, and how our thinking reflects contemporary debates.

Free India constituted itself as a Union of States, incorporating many features of a Federal State – which means a union of various self-governing States, whose self-governing status as well as the division of power between the State and the Union was constitutionally entrenched, incapable of being altered by unilateral action of either party. The founders of the Indian constitution realised that introducing the federal elements was inevitable to negotiate with India’s inherently diverse, multi-ethnic and multi-lingual population.

The federal structure reinforced

India’s multi-cultural ethos

The division of power in India, between the Union and the States, including the power to levy and collect taxes, is provided in the Constitution of India. Its Seventh Schedule provides three lists, viz.: a list of subjects on which only the Union can legislate any law (‘the Union list’), a list of subjects on which only States can legislate any law (‘the State list’) and the list of subjects on which both Union and State may legislate law (‘the Concurrent list’). One of the significant subject matters covered in these lists is the power of the Union and the States to levy tax. I think that this power is a necessary corollary to their governing status. However, like most other administrative and financial powers, the power to levy and collect taxes also tilts in favour of the Union.

It is unlikely that the division of power to levy and collect taxes on various subjects between the Union and the States has had anything to do with the ethnic or lingual character of the States. Presumably, it is a continuation of the British legacy of assigning to the Union list most of the broad-based taxes having higher revenue potential, lower collection cost, and positive correlation to economic growth. These include taxes on income and wealth (other than agricultural sources), corporation tax, taxes on production (excluding those on alcoholic liquors) and customs duty. States were assigned a long list of taxes, and the most significant one includes the exclusive rights of States to tax agricultural income and wealth. However, taxes on agriculture did not emerge as a significant revenue source for the various States. It is possible that rich landlords gained political eminence and became people’s representatives in State Assemblies, and did not allow for any significant taxation on agricultural income and wealth. The State Administration’s failure to collect charges on electricity and other State-run infrastructures may also possibly be attributable to same or similar reasons.

Historically, only taxes on the sale of goods (which falls in the concurrent list) turned out to be a significant source of States’ revenues. But even here, the ability of the States to levy tax on the sale of goods becomes limited because the production of those very goods is already subjected to excise duty (a Union subject). Again, if the goods are sold outside the State where it is sourced (inter-state sale of goods), the Union also claims a right to tax such sale. As the Indian service industry grew in leaps and bound, taxes on service became the Union subject. In its turn, the Union is under constitutional obligation to pool and share its revenues with the States.

The latest debate around taxation concerns the Goods and Service Tax (‘GST’). When it gets legislated, it will probably be regarded as the most fundamental tax reform in India, and I would think, for the right reasons. The proposed GST regime seeks to provide a unified system of taxation on goods and services across the country. This will make the entire country one local market, as opposed to differentials in prices in respective States, due to local tax differentials. With the introduction of the GST, State level taxes like Octroi/Entry tax, VAT, etc. and Central taxes like Excise duty, Sales Tax, Service Tax, etc. will get integrated into one tax, with unified chargeable event, input tax credit, documentation, classification and rate of taxation. The Government gets a uniform fiscal tool to influence demand and supply. Business will then have to deal with compliance and litigation (if any) of only one tax. This is expected to improve compliance, thereby increasing revenues, and reducing corruption.

One of the hopes of GST: curbing corruption

The balance of financial power in favour of the Union (just like the legislative and administrative powers) keeps the Union strong, enabling it to hold the States integrated as a nation. This, however, increases the responsibility of the Union to administer taxes in a manner that furthers the welfare of its people in the States. As we noticed, the federal elements of the Indian constitution evolved, not by choice, but by necessity – given the multi-ethnic and multi-lingual diversity of Indian population. There seems to be a presumption that government welfare is limited to taking care of the basic needs of food, sanitation, health and education. This is far from truth. What one has been overlooking is that people of any culture are held together, not in their struggle for meeting their economic needs but by their identities born of their cultural uniqueness – this is particularly true of India. If this cultural identity is consistently divorced from their economic life, the economic needs will eventually take the better of the cultural self. Much of this happened during the colonial rule. Post India’s independence, the cultural ethos has been lost sight of in the nation’s struggle to improve the economic lot of people. This is not because we do not care but because our economic lives are divorced from our own respective ethnic and lingual culture.

This important, and in my view historic fiscal transformation of introducing the GST, adds one more unifying character to our nations’ economic life. This is a welcome step, and it does not by itself threaten the pluralistic ethos of India and its traditions of exchanges. But what it does recall, is how removed the Union-State debate is from this basic nation building concern. The Union-State debate on the GST, which seems limited to issues of sharing revenues, does not apparently include any discussion on what is the consequence of taking away an important fiscal tool from the States on their respective people. No one is asking what those economic activities that upkeep cultural, ethnic and lingual traditions may be, and if they need any dispensation and support. As a result, it appears that any debate on the impacts of GST as a fiscal tool and its ramifications on this aspect of nation building is indeed inconsequential.

The dialogue on GST is expected to be ongoing in the course of its implementation – it can serve us well to recall and use this as an opportunity to actively initiate and hold dialogues on how the economic lives of people can be wedded to their ethnic identity and culture, and how they contribute to national identity.

|