10 March 2014In his 1949 book, Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. coined the phrase ‘the Vital Centre’ to refer to the contest between democracy and authoritarianism. Sixty-five years later, we are faced with an acute political dilemma in India. Are our dreams of liberalism challenged by a growing conservatism within democracy? Or is our democracy itself threatened by a totalitarian movement from without? This is the starkest question that our national political parties are confronting now, as India runs up to General Elections 2014. The problematic seems to be presenting itself more intensely to the Bharatiya Janata Party, with the emergence of an arguably new brand of personality-oriented politics within its own administration. For our second issue of The Citizen Politician debate series, senior leader Jaswant Singh discusses the criticality of following the middle path, and creating a vital centre within the party. In her response, journalist Vidya Subrahmaniam critically assesses the BJP’s claims as a centrist party, and the hurdles that it has to cross before reaching this goal. |

Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations and descriptions.

The Middle PathJaswant Singh |

A Double-Edged GameVidya Subrahmaniam |

|

Contemporary Indian politics seems to be marked by an intriguing competition between the extreme — which involves different polarities — and the moderate. And, the extreme tends to win more often than the moderate, for, it is rather easy to carry the flame for a brief while. But the profound irony of our circumstance lies in the fact that what we see and hear today do not belong to the true extreme at all—these elements do not have the extreme passion that invariably collapses from its own intensity, dies by the same fire that it tries to inflame, thus ultimately making the participants realize that the extreme is not the answer. The truth is, we are now going through a decadence, a mere pretense of passion. And, where it would lead us politically is open to debate. India, by its very nature, has always sought a resolution for a moderate, accommodative politics for its continuance. In this country, we have an almost indefinable, indiscernible thread that strings us together, across the hills, the desert, the coast. Political actors must try and discover that invisible connecting string, for, our answer cannot be found in pursuing any extreme of thought, conduct or behaviour.

In ’47, we went through a partition, because it seemed separation would be the end of the turmoil; there was hope that it would bring peace. But peace has since abandoned South Asia. The bus trip to Lahore was an attempt to restore peace and some accommodation. A national political party like the BJP cannot consider such an endeavour to be a single person’s ideology or inheritance. The party as a whole must aspire to seek precisely that mandate in order to go beyond the present moment, and continue. It must come from the realization that we have to think and act beyond manifestoes, which are mere externalities. The BJP necessarily has to emerge as the integrator, not the disintegrator, in these times. Let us look at the political map of India today—it seems so disjointed. The Congress is terminal; it is flogging itself to keep it going, its articulation is not at all coming across as credible. The BJP is struggling even as it is endeavouring to search for a voice. The history of the world and our own historical experience in India inform us that it is a certain weakness in structure that impels an administration to forgo the middle path of moderation and push the finite individual to the foreground. We saw it in the case of Indira Gandhi, and time shall offer the same lesson to anyone who tries too hard to make a similar move. Evidently, no party can win this asymmetrical country with mere numbers or by managing an electoral success. The numbers do not really total unless we encourage greater debate, and actively invite dissent. In the context of the emergence of the Aam Aadmi Party, the principal national parties of India must introspect: What is it that they do not provide the citizens? Is there some lack, a vacuum or lacuna which has caused this new political development in the country? Now that the AAP has brought home these questions to us and created a chink for reflection, even if they fail in delivering their own promises, in some form or the other, an alternative idea, an alternative thought, an alternative methodology, would keep pushing itself, and claim the attention of every citizen. Has the emergence of AAP shown that there is a lack in what the major Indian parties are providing the citizens? It would require deep reflection and brave historical studies to understand the roots of our political dilemma today. Even though our fast-paced world does not readily offer many media spaces that allow subtle levels of contemplation, in order to take redemptive steps and arrive at the heart of our democratic dream, it is imperative that we initiate this discussion. I would say our original political sin was the adoption of the concept of the nation-state — a concept which was born in Europe. Are we a nation at all? We call ourselves a ‘rashtr’— is rashtr equal to ‘the nation’? People had lived in these parts for centuries with no concept of a unified state, and yet India had been thought of as a civilizational ‘rashtr’ — an utterly non-territorial one. Here, I am questioning our constitution’s foundations in the Government of India Act of 1935, which merely reflected what the western mind had thought of governance in that context. While almost adopting it as our country’s governing document, we forgot that the functioning of the British parliament had improved through a series of reform bills during the Victorian times. We had to study those bills to see how they slowly gave rise to a better constitutional practice in Britain, and then find our own way of making a constitution that suited our variegated civilization. We did not do it, and that historical error will continue to haunt us. A country like India cannot afford a governance rooted in the construction of the nation-state. A very wise PN Haksar once told me that the cellular core of our country is our society. It is the society that has kept us afloat through centuries of want, and deprivation, and conquest. And now, for the first time perhaps, the state of India is attacking the seminal core that is our society. Our society has always had a self-cleansing mechanism, and we are destroying that by implanting it with ideas that originate in Delhi and cannot be uniformly tried across the country. Somehow, Gandhi had caught the flavour of our societies, but he could not go further. Towards the end, apparently, he too had the fear of failure. Unfortunately, the present political discourse lacks the profundity to recognize such deep sentiments and address them.

In this tentative world, India will have to readdress itself to the questions related to all types of connections as well as disconnections — knowledge, warfare, peace. We have to review the whole question about the weapons of mass destruction at this time. For instance, what is a nuclear weapon today? It is not an actual war-fighting equipment; it is a virility symbol, and a figurative means of safety. You have it, so I also have it — no more than that. So humankind has to wake up and understand that our weapons no longer suit the description of weapons, and for the same reason, ironically, the extreme sense of safety that we are deriving from them cannot be real, too. Ask without Thinking? When a right becomes an obsession, The seminal question here is how we are trying to understand, to know. We must realise that knowledge accessibility and the right to know are two separate things. When one refers to knowledge accessibility, it envisions a world where humankind is free to search for knowledge and acquire it. It is about questing for knowledge, which should help us find answers to our deeper questions. We often confuse accessibility to knowledge with the right to information. Information is related to governance, and in today’s governance one cannot allow unlimited flow of information to everyone at all times, lest premature or unwanted revelation of information caused us collective damage. As I mentioned, the BJP, as a national political party, has to address these questions in order to arrive at a path of governance that is appropriate for our society and our times. For a party that aspires to win this country’s heart, this is as much a challenge as winning the polls. We are truly at a tipping point, in every sense. Where we go from here is again dependent on the larger question of our understanding, our knowing, and our openness to follow the moderate way. At this point, not just the political players of our country, but humankind as a whole has to wake up to the middle path, indeed. |

With the Parliamentary polls just round the corner, a curious simultaneity is playing itself out in Indian politics. Thanks to the perceived corruption and misrule of the UPA, the Gujarat model of development has become a legend, a myth that people would buy into, simply because they are desperate and see no alternative. Indeed, there is a despair in the polity today, which the BJP and its PM candidate are exploiting to the full by their stress on development. The irony of this situation is, most voters from the Hindi belt do not understand this model, nor do they know Narendra Modi as they would a politician from the North. Yet Modi’s specific advantage is that his emergence has coincided with the UPA’s ten-year anti-incumbency.

The BJP’s history shows an attempt to balance the art of the possible with the goal of polarisation. The party has an enviable record in terms of alliance building. Under Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the NDA reached a peak of 22 allies. With Modi in command, this project has taken a knock; one of the BJP’s oldest allies, the JD(U), departed the NDA citing its inability to co-exist with Modi. However, the BJP’s PM candidate is slowly overcoming the resistance to his persona and has succeeded in achieving a few small but significant breakthroughs. The symbolism of Ram Vilas Paswan’s LJP returning to the NDA fold under Modi cannot be dismissed lightly. Paswan was the first to quit the NDA in protest against the 2002 anti-Muslim violence.

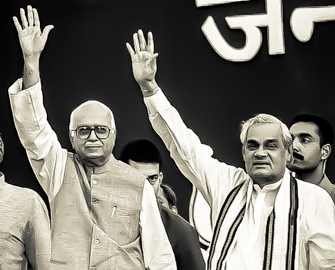

On the other hand, the BJP’s philosophy is Hindutva, which thrives on polarisation. Reaching out and polarisation are contradictory impulses, and yet in a place like Uttar Pradesh, one can see both impulses at play, as the BJP attempts to expand its voter base while retaining its core vote. U.P. is central to the BJP’s calculation of achieving an overall Lok Sabha tally of 200 seats. It needs to win a minimum of 40 seats from the State if it is to reach the larger target. Towards this end, Modi has assumed multiple avatars: he is at once macho man and poor tea-boy with OBC origins. But Modi is also aware that this expansion could alienate the core vote, and thus also his reliance on confidant Amit Shah to keep the Hindutva cinders burning. Shah has been promising the Ram mandir; he has also lent covert support to the polarising project in communally sensitive places like Muzzafarnagar. So, the perception that the BJP under Modi is shifting to the middle ground is, in my view, incorrect. Today, as before, the BJP wants to attain power. The mission may look easy, especially with the growing popular support for Modi. However, the Gujarat Chief Minister is not merely a polarising figure, he is authoritarian with almost no tolerance for dissent. The BJP’s earlier stint in power was made possible by Atal Bihari Vajpayee being at the head of the NDA. Vajpayee is, even today, very popular, and his USP is his ability to adapt himself to the demands of a situation. Thus he could at once be a moderate with his allies and play the Hindutva card while appealing to the core voters. Besides, at that time, there was the Vajpayee-Lal Krishna Advani compact, by which the former appealed to the moderate sections and the latter to the core constituency.

Now, in the absence of Vajpayee and Advani, Modi has the tough job of combining both in his own identity. Modi’s inflexibility makes the task that much harder. Recently, BJP chief Rajnath Singh offered Muslims what seemed like an apology for past mistakes. However, soon thereafter, he retracted and tweeted that the Congress needed to apologise, not the BJP. Modi has not even gone this far. When, last year, Reuters asked him if he regretted the 2002 violence, he took refuge in generalities, and gave the analogy of a puppy coming under a car. Modi is aware that a fair bit of his appeal derives from his muscular, macho, anti-Muslim image. He will not want this diluted. In other words, the occasional conciliatory gesture he and the BJP under him make towards Muslims cannot be taken as a genuine change of heart.

And yet India is a country of such spectacular diversity that no party or alliance can sustain itself in power without treading the middle ground. Vajpayee achieved this by a combination of his own middle-of-the road image and taking into the NDA, parties which are fiercely secular in character. The participation in the NDA of Mamata Banerjee, Nitish Kumar and Naveen Patnaik, all with large minority populations in their States, lent a measure of credibility to the NDA. The BJP’s Hindutva was balanced by the centrist orientation of the allies. The allies, who joined the NDA because of the ‘genial, accommodating’ persona of Vajpayee, started to exit from the same alliance post the 2002 Gujarat anti-Muslim violence. This establishes two things. One, the allies may be wary of the BJP’s Hindutva but they will align with it provided it has a leader capable of taking along everyone. Two, if the BJP flouts the compact by openly targeting the minorities, as happened in Gujarat and later in Kandhamal, the alliance will break. This is for the simple reason that beyond a point the allies cannot hurt their own vote base.

On the election trail, it is easy to win appreciation by loud attacks on the Congress and jokes on the dynasty, but the BJP cannot replace the Congress, which for all its faults, has a liberal core. The one area where the BJP has traditionally scored over the Congress is in the area of internal democracy – the BJP’s claim is that it believes in collective leadership as opposed to the Congress’s reliance on the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty. And yet, if one looks at the BJP closely, one would find that it has always projected a single larger-than-life figure. In the Ram temple phase, it was Advani who dominated the party. Vajpayee became the BJP’s winning mascot post 1996. It might be worth recalling that the BJP included 70 photographs of Vajpayee in its 2004 manifesto. There were also recorded personal messages from Vajpayee to individual voters. So the BJP’s projection of a single individual today is not a break from the past. However, Modi is seen as someone who brooks no dissent, and party insiders worry that he would be intolerant of rivals. Two examples are often quoted to illustrate Modi’s power within the party: RSS pracharak Sanjay Joshi was ousted from an insignificant position in the BJP because he once dared to take on Modi; Advani, who had resisted Modi’s elevation to Prime Ministerial nominee, was completely isolated and was left with no option but to accept Modi’s leadership. Modi’s tremendous charisma and his offer of utopia via the Gujarat model are the reasons why he has become so popular today. His way of circumventing the image problem is by hardselling development, which, judging from ground reports, is paying him high dividends. However, if and when Modi gets into government, he will no longer be able to put off the question: how does he balance the Gujarat model – which in its essentials is corporate-driven development – with the requirements of social and distributive justice? The growth and development narrative worked wonders for Modi in Gujarat but India is a diverse country of many castes and communities, the majority of whom are poor. In fact, Modi in power has to reckon with the fact that subsidy and welfare have become state policy under the UPA Government. MNREGA and Food Security are measures that cannot be reversed. However, the corporate sector is backing Modi to the hilt precisely in the hope that he will opt for a high-growth, no-subsidy trajectory. The BJP tried to be centrist under Vajpayee and succeeded as long as the allies were able to pursue a common, non-sectarian agenda. The allies forced the BJP to exclude the Ram Mandir and other contentious issues. But in the aftermath of Gujarat 2002, and closer to the 2004 elections, they began to depart from the coalition out of deference to their own moderate constituencies. If the BJP under Modi touches 200 Lok Sabha seats, it is a fair bet that the party will able to get the bigger parties to join in. However, history shows that for a ruling alliance to sustain itself, its centre of gravity has to be in the middle. |

|

Jaswant Singh is a senior politician, previously affiliated with the Bharatiya Janata Party. He resigned his commission in the Indian Army to pursue a career in politics. In the BJP-led governments of 1996, and 1998-2004, he held charge of six ministries including Finance, External Affairs and Defence. He was the leader of the opposition in Rajya Sabha during 2004-2009 and is currently representing Darjeeling in the Lok Sabha. He has authored many books on current affairs and history.

|

Vidya Subrahmaniam is Associate Editor with The Hindu. She has been a commentator on national political affairs since 1994. Vidya Subrahmaniam specializes in the electoral politics of the Hindi belt. She has written extensively on the politics of communalism, social justice, party politics dynamics, democracy and civil liberties. She has won the 2010 Ramnath Goenka Excellence in Journalism Award for the Best Commentary and Interpretative Writing of the year.

|

Disclaimers: The opinions expressed by the writers are their own. They do not represent their institutions’ view.

LILA Inter-actions will not be responsible for the views presented.

The images and the videos used are only intended to provide multiple perspectives on the fields under discussion.

Images courtesy: Jason Berensci | Prakash Singh | AP for BBC | Aid India | Sharasamay | Rediff

Share this debate… |

… follow LILA… |

||||