1 August 2014Where is the queer? Once a derogatory term for homosexuals, it became a subversion, accompanying the LGBT emancipation movements of the last half-century. But the queer remains on the run: contesting primarily heteronormativity in its early form, it widened its scope to address the very conception of fixed gender and sexual identities. The queer permits to transform artistic, cultural, intellectual, social and political experiences into ever changing, moving and ambiguous events. Thus, indeed: where is the queer? How to locate it without fixing it? How can an indefinite object be expressed and shared? If its raison d’être is the contestation of binaries, can we expect of queer movements to be the models of a transcended content/form opposition? What can the queer bring to the fields of communication and the arts? And, when the queer is discussed or represented, is this process of translation itself, inversely, redefining the queer? To start a new season at Inter-actions, we invited two major voices from the vast and multifaceted reality of today’s queer. Pramada Menon reflects on the object and technical choices of her 2013 documentary And You Thought You Knew Me, stepping away from the popular images of the queer movement. For Malaysian Bharat Natyam artiste Mavin Khoo, dance reveals a performative rediscovery of the queer, pushing it even beyond concerns of sexuality and gender. |

Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations and descriptions.

Besides the SpotlightsPramada Menon |

Considering the Queer LineMavin Khoo |

||||||||

Requested file could not be found (error code 404). Verify the file URL specified in the shortcode. |

Listen |

Listen |

Requested file could not be found (error code 404). Verify the file URL specified in the shortcode. |

||||||

|

Amongst the many social movements in India, the sexual rights movement has increasingly come to be defined by the work done in the last ten years around the legal reading down of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code. There has also been a narrowing down of the sexual rights movement to be seen as one that addresses the need of those outside of the heterosexual framework and/or those who choose to identify themselves with the terms of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transwomen, Transmasculine, Intersex and the countless other indigenous terms such as Hijra, Kothi, Jogappa, etc. The understanding of sexual rights has increasingly become limited and tends to veer towards disease prevention or the concretisation of identities. Not all people who have same-sex desires or are questioning and living their lives in a gender other than that they were born into, choose to enter the political or public space. A large number of them are living their lives in the way they know best and engage with the everydayness of the world around them. Some others occupy the public arena as a way of challenging patriarchy; some do not ‘pass’ as being male or female – the only accepted definitions of gender identity – and some choose activism. Thus, public focus becomes part of their world. Activism is the most familiar face of the queer movement Increasingly, in urban areas of India, there is a newer definition emerging, that of a queer movement. Queer is defined as “encompassing a multiplicity of desires and identities, each and all of which question the naturalness, the rightness and the inevitability of heterosexuality” (Arvind Narrain, Challenging the Rule(s) of Law). The queer movement in India represents for many, an understanding of sexuality that goes beyond the categories of ‘homosexual’ and ‘heterosexual’. Queer politics speaks of a larger understanding of gender and sexuality in Indian society and integrates within it a politics of class, caste, gender, religion, ethnicity… Therefore, it acknowledges the myriad ways in which identity is all but monolithic. The queer lives in focus in public spaces are few and mostly represent those who are public in the acknowledgement of their identities. Often, the narratives of movements are those linked to those of activism and are a listing of what has been achieved for a larger public good. As John Berger says in his April 2006 article, “Wanting Now”: “A movement describes a mass of people collectively moving towards a definite goal, which they either achieve or fail to achieve. Yet such a description ignores or does not take into account, the countless personal choices, encounters, illuminations, sacrifices, new desires, grief, and finally, memories, which the movement brought about, but which are, in the strict sense, incidental to that movement.”

I was tired of the representation of queer People Assigned Gender Female at Birth in the media, in people’s imaginations, in their everyday life. I truly wanted to question it. I wanted the ‘imagined’ queer woman to talk directly to whoever was willing to listen. I did not want to place the person in any fixed identifiable space, but wanted the listeners to just listen to what was being said and focus on the intricacies of the story being told. I wanted my film to turn into “a radical archive of emotion in order to document intimacy, sexuality, love and activism – all areas of experience that are difficult to chronicle through the materials of a traditional archive.” (Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings, 2003). Because history is not just the story of those who occupy center stage in any process, it is also the story of the many, many people whose lived realities offer a new way of loving and living and challenge paradigms of existence. I never intended for this to be a film. I am not a filmmaker. I love watching films, and wanting to see my name up on a screen as director has been a dream… But the reason why I made the film is because there were stories to be told. Once I knew who the characters were going to be, I had to figure out where to shoot, since two of them did not want their faces to be shown. I love Delhi. I have lived in Delhi for most of my life and have watched this city go from being queer unfriendly to being somewhat friendly and more open. Of course one would wish for much more. I was also conscious that the friendliness is extended to men and not necessarily to women, because, here, there is no notion of women loitering anywhere. Therefore, I also used the film to lay claim to public spaces, where lovers are to be found – but heterosexual ones, obviously! I love the beauty of the monuments, the stories that lie behind those stones, the histories associated with the spaces. Clearly, the images of Delhi are also my love letter to a city that everyone loves to hate. A city where people have the luxury of encountering a 14th century monument as they try and avoid the clutter of an urban village! I wanted to show the modernisation that has happened – the metro, an unrecognisable Connaught Place, and indeed, this urban village; and yet within all of this the deep conservatism that exists on matters related to the ‘other’. Whose romance is visible in India’s public spaces?

Often, when we view a film, our minds create a counter narrative through the images that are presented. A photograph makes us wonder about the person’s life; we interpret the image with the vocabulary available to us. I did not want to provide the viewer with any such luxury. I wanted the viewer to engage with what was being shared – a personal journey of the individual. What you hear is what you get, you may want more but they do not want to share more. Can we be happy with that? In these days of tell all show all, I wanted to make sure that people listened, with minimal clutter. This film is a journey that viewers embark on. There are no conclusive statements made, it is the story of five queer Persons Assigned Gender Female at Birth. There are many other narratives that exist and can emerge if people searched for them. When people listen, take stock and understand, maybe, the ‘othering’ will stop. And perhaps through this engagement with And You Thought You Knew Me, one day they will begin to know. And You Thought You Knew Me: trailer |

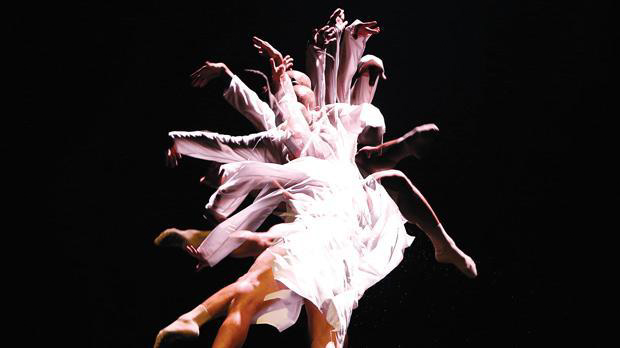

I am Malaysian – I have a Sri Lankan mother and a Chinese father. I am of a London sensibility – I am deeply rooted in South Indian values. I believe in frameworks – I don’t believe in frameworks. I am Queer – I am not queer. I am present – I am the past. I am Bharata Natyam – I am Ballet. I am religious – I am a hedonist. I am sacred – I am impure. I am Man/Woman – I am neither. Modern make up I was preparing to delve into the sacred composition of Adi Sankaracharya, which famously describes the ambiguous construct of Ardhanarishwara (Siva as half man – half woman). I had seen several choreographic versions of the work and I adored the compositional beauty eluding the binaries that determine the masculine and the feminine. Siva and Shakti stood as the primal energy of movement in their co-existence. Predictably, I found myself creating movement that on the right side of my body suggested masculinity. I was more grounded; there was more attack and aggression. The left fell into lyricism, almost clichéd in its superficial coyness and fragility. Something seemed to bother me. The stereotypes that were uncreatively being developed were easy options to what should have been complex and ambiguous in nature. As I went back to the written text, I became more intrigued by the simple repetition of the line that would consistently anchor each stanza. The chorus of ‘Namah Sivayaiche Namah Sivaya’ stood as the line that ‘allowed’ for the gendered expressions that elaborately adorned the verses.

It seemed clear to me, that as much as the physicality of movement allowed for the gendered binaries to become visual, the movement of stillness was the anchor that permitted the binaries to speak. I looked on to an image of Ardhanarishwara and the obvious oppositional sides; right and left, virile and effeminate, male and female. The passage ‘Namah Sivayaiche Namah Sivaya’ suddenly found itself within the central line of the figure. Here was where the unobvious lay. Fluid, consistently moving in its intangible stillness and merging whilst splitting; a queer line of ambiguous androgyny. Mavin Khoo exploring stillness My fascination and identification with what I refer to as the ‘queer line’ urges a continuing attempt at identifying the nature by which the potential layering of experiences occurs to build the foundation of my identity. Placed under my own personal bodily text, my performance practice aims at suggesting that the premise of androgyny within the ‘queer line’ should be considered through the constructive layering of histories, which contain binaries in them, not necessarily of genders, but, of cultures, lives and experiences, all existing as the interstice of my performative presence. This is potentially what makes it androgynous. The image of Ardhanarishwara that became pivotal in my query created a performative dialogue between God and Bhakta, the icon and the spectator. Siva and Shakti carried with them their own histories of culture, location, politics and values that seemed to create an interpretive dance when partnered through the construction of image and the de-construction of the gaze. As I continue to develop my practice as a performer, choreographer and teacher, it seems that there is a further need to examine the ‘construction’ that lends itself to what arguably can be considered as an intangible performance of presence. This presence is potentially the product of an artistic intuition from ‘an inner self’ that has been developed through 25 years of performance practice. This intuition might be one that has been developed, firstly, through the inscriptions of my rather unique dance training, secondly, by the hybrid nature of my locative surroundings, and thirdly, by a developed self-awareness of the constructed ‘Mavin Khoo’ that may be read by the viewer, both in and out of the theatre context. I too carry with me my own histories, cultures, locative homes, politics and values and attempt to ‘perform’ the revealing of these bodily inscriptions to the spectator of the constructed presence. Like the Ardhanarishwara that stands before me, I search for my ‘queer line’ in order to fluidly act as an anchor to my layered histories and to help consider why I could be identified as an androgynous construct.

Arguably, there is for me a personal aim at channeling the perspective of androgyny seen merely through the gendered frameworks of masculinity or queer studies, within the context of Western queer politics. I urge the reader of my body, the viewer of my texts to consider the relationship between my personal histories and Dance in me, and to consider these complexities as androgynous ‘subtexts’ of bodily dance, of ‘lived’ dance. Arguably, this androgynous lived dance is embedded in a canvas of pluralism beyond the specificity of gender binaries, be it male/female/straight or even singular in being queer. Indeed, ‘queerness’ needs to be considered beyond the accepted or known framework that underpins its potential and limited considerations of gender and sexuality. Twirling the definitions of the queer As a result, my practice suggests an alternative definition to the androgynous state. It is intended to present a discourse that will allow for a broader interpretation of androgyny as a potential interstice between binaries. That these binaries can be seen beyond the constructs of gender. That they can be inscriptive histories, and that those histories can achieve the ‘state’ of androgyny not just from a psychological or physiological perspective, but through a transcendental state of purity determined by a middle point of queerness – a queer line marked by the Ardhanarishwara that resides within. Om Namah Sivayaiche Namah Siva |

||||||||

|

Pramada Menon is a queer feminist activist who has been working on issues of social justice for more than two decades. She is the co-founder of CREA, a feminist human rights organisation based in New Delhi. Pramada is also a stand up performance artist and her show Fat, Feminist and Free has been performed in many spaces in Delhi and Mumbai. Last year, she made her first documentary And You Thought You Knew Me, a look at the lives of five queer People Assigned Gender Female at Birth living in Delhi.

|

Mavin Khoo is internationally recognised as a leading Bharata Natyam soloist, a contemporary dancer, choreographer and artist scholar. He studied Bharata Natyam with Padma Shri Adyar K.Lakshman, Cunningham technique in New York and classical ballet with Marian St. Claire and Michael Beare. He has worked in collaboration with Wayne McGregor, Akram Khan and others. Khoo’s company mavinkhooDance was founded in 2003. As a practice based researcher, his main area of exploration examines notions of androgyny in performance within the frameworks of classicism and philosophy. He is Rehearsal Director for Akram Khan Company and has currently been appointed the first Artistic Director of the national contemporary dance company in Malta.

|

||||||||

Disclaimers: The opinions expressed by the writers are their own. They do not represent their institutions’ view.

LILA Inter-actions will not be responsible for the views presented.

The images and the videos used are only intended to provide multiple perspectives on the fields under discussion.

Images and videos courtesy: Simon Tolhurst | Yemisi Ilesanmi | AFP | PSBT India | Random Clicks | Mavin Khoo | Di-ve

Voices courtesy: Samuel Buchoul

Share this debate… |

… follow LILA… |

||||