In my earlier avatar as a sculptor, I was well known for doing figurative work, which was quite performative and theatrical, really, and handcrafted, tactile. At the time, I was interested in creating an indigenous language to deal with the contemporary, inspired by Indian classical and folk sculpture and working with terracotta. I started moving away into making objects and minimalist installations in the early 1990s, responding to the events of the time. By the mid-nineties, I was feeling cornered, sensing that I was somehow whittling away my real (somewhat excessive and baroque!) self, when by chance I decided to do a photo-performance work for a group show on cinema, a jokey take on Fearless Nadia inspired by Bhupen Khakkar’s early catalogue photographs of himself as Superman. The initial shoot looked so interesting that I began developing it into a narrative, a photo-romance. This was a very different way of working, involving research, scripting, planning, collaborative production work and editing. A friend said what is interesting about my photo-performances is that I put myself in a set or location like a living sculpture, which is then photographed. While my earlier sculpture was very artisanal, my present work is conceptual, and what unites them is my interest in detail and craftsmanship. The ‘beauty’ lies in how they are put together and the ‘beauty’ or ‘gravitas’ of my physical self is in how it works within the frame, within what I am trying to say. While I am interested in the idea of visual pleasure, of ‘rasa’ or ‘juiciness’ – in making the images rich and sensual rather than bare and minimal – the layers of references from art and life, the theoretical underpinning of the work and the rigourous research behind it give it conceptual weight. In my earlier avatar as a sculptor, I was well known for doing figurative work, which was quite performative and theatrical, really, and handcrafted, tactile. At the time, I was interested in creating an indigenous language to deal with the contemporary, inspired by Indian classical and folk sculpture and working with terracotta. I started moving away into making objects and minimalist installations in the early 1990s, responding to the events of the time. By the mid-nineties, I was feeling cornered, sensing that I was somehow whittling away my real (somewhat excessive and baroque!) self, when by chance I decided to do a photo-performance work for a group show on cinema, a jokey take on Fearless Nadia inspired by Bhupen Khakkar’s early catalogue photographs of himself as Superman. The initial shoot looked so interesting that I began developing it into a narrative, a photo-romance. This was a very different way of working, involving research, scripting, planning, collaborative production work and editing. A friend said what is interesting about my photo-performances is that I put myself in a set or location like a living sculpture, which is then photographed. While my earlier sculpture was very artisanal, my present work is conceptual, and what unites them is my interest in detail and craftsmanship. The ‘beauty’ lies in how they are put together and the ‘beauty’ or ‘gravitas’ of my physical self is in how it works within the frame, within what I am trying to say. While I am interested in the idea of visual pleasure, of ‘rasa’ or ‘juiciness’ – in making the images rich and sensual rather than bare and minimal – the layers of references from art and life, the theoretical underpinning of the work and the rigourous research behind it give it conceptual weight.

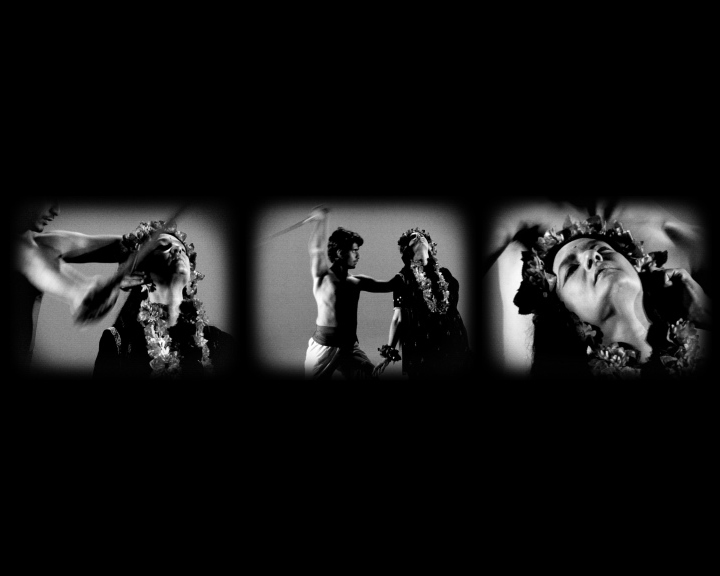

Pushpamala N in collaboration with Mamta Sagar Motherland live performance Bangalore 2011

When feminist artists revolted against the machismo of modern art practice in the 1960s and started reclaiming emotion, narration and craft, performance art was also crucial to critique the male gaze and to take control. I use ‘low’ forms seen as feminine, like the photo-romance and love story, recipe books or hysterical women characters, while appropriating ‘masculine’ forms like the detective thriller and the epic. The absurdity, humour, irony, parody and satire central to my work are normally considered aggressive and unfeminine qualities. I like to use a heightened melodrama and emotionality, which, strangely, many men too find moving.

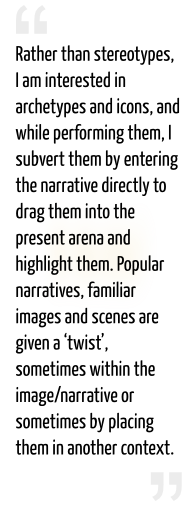

My body and very self-conscious contemporary persona is the main tool I use to deconstruct popular narratives of women. Rather than stereotypes, I am interested in archetypes and icons, and while performing them, I subvert them by entering the narrative directly to drag them into the present arena and highlight them. Popular narratives, familiar images and scenes are given a ‘twist’, sometimes within the image/narrative or sometimes by placing them in another context. Sometimes, the twist is in my own body inhabiting that unexpected image. In Phantom Lady or Kismet, I take an action adventure and use the film noir style to inject melancholy and vulnerability, where the heroine is not a superwoman and the ending is not a ‘win’. Susie Tharu described my work as a sort of inventory, or even a grammar, and what I do is to take material from personal memory, from my entire range of interests, what I have studied and read (whether ‘high’ or ‘low’), or what I experience everyday, and create a sort of archive, not a classic archive but one that displaces categories and connects disparate things, so that you can ‘see’ them afresh. So, recreations of a Ravi Varma Lakshmi, a Yogini from a sixteenth century miniature, a Toda tribal and a contemporary criminal might exist together in a series under the title of ‘The Native Types’.

Pushpamala N Phantom Lady or Kismet a photo-romance set in Mumbai photography: Meenal Agarwal black and white photograph 1996-1998

My work is full of irony, but I love all those images and references that I like to deconstruct. All those strange, problematic, wonderful images, characters and stories (and not only cinematic) are part of my personal memory and the cultural memory of this society. I like my work to teeter on the edge of emotional involvement and distanced critique, where the spectator at once identifies with the situation, but then realises that all is not what it seems. I work like a filmmaker or theatre director, producing, directing, scripting and acting in my own dramas. I do not photograph myself but work with different kinds of photographers: some professional, some commercial or just friends, with whatever equipment they have. This connects me to various histories of photography, where I can meet and collaborate with interesting people on the way, like the late JH Thakker, a wonderful man who ran the India Photo Studio in Mumbai, and took the legendary portraits of the 1950’s Hindi film stars, which are so mesmerising. Their personas and stories also become a part of my work. I am interested in set, location, mise-en-scène and lighting, which create the emotion and atmosphere. The performative aspect is minimal, actually, the more I try to emote the more silly or weird or hideous it looks. My work also connects to a grand old tradition of dressing up and masquerade in photography (and life), which you can see in all the photo studios. And my friends, all amateurs, perform as various characters that act like a hidden joke.

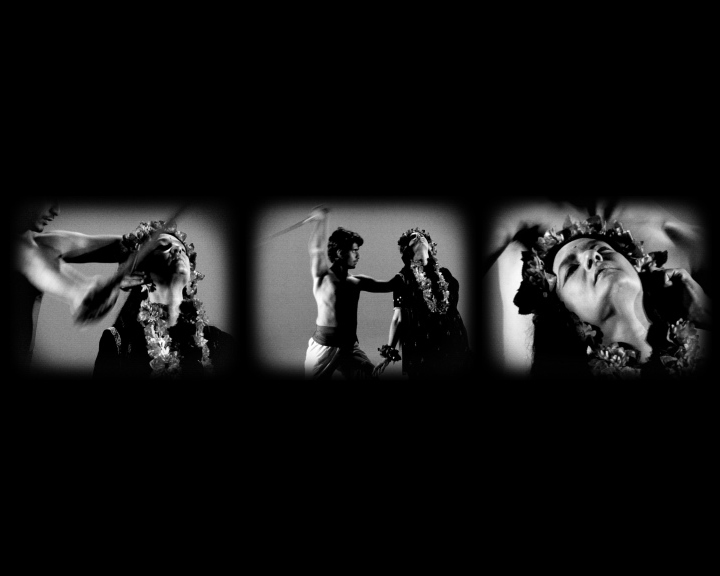

Sometimes, I may change things completely in the middle of a shoot. When working on the Indrajaala / Seduction video, which shows the cutting of the nose of Surpanakha from the Ramayana, I decided to change a costume. We rushed to the National Market in Bangalore at night, where I bought myself some clothes. While in the earlier version I was wearing a short sari and a mask, the new costume was a long skirt with garlands, showing my exposed face. As we were shooting, I had decided to do close ups for the sequence and realised that an exposed face would be more vulnerable and expressive than a mask, and what was needed was a more flowing costume to emphasise the dance. If masked, the character would have been puppet like, while the unmasked one would be more empathetic. Like any other artist, I have to grapple with the material conditions in which I work, which includes my own resistant body, the people I work with, the place or location, and my access to technology and expertise. The challenge is to make a profound work of art with all the limitations. The improvisations and transformations, editing and reworking are to try to create a coherence and integrity in the work, an internal logic and clarity of conception to make it more powerful.

Pushpamala N still from Indrajaala / Seduction video installation 2012

My work is about creating tableaux, scenarios. I create the mood or the ‘rasa’ through location/set, costumes, props and lighting and the physical gestures and poses. All the elements are put together to seduce the spectators, to make them enter the work. Performance art is quite different from acting; it is abstract in form, and indicates something without overtly describing it. I am too busy while shooting, directing the photographer and other performers, and dealing with all kinds of details as producer to internalise an emotion. But the internalisation could have already happened during the period of research for the project when I read, think and make notes, decide on the poses, style and lighting, and conceptualise the whole thing as it should be. After seeing my first live performance, where I sit quietly knitting on an elaborate stage dressed as Bharatmata, Maya Krishna Rao said that I should have made some satirical expressions and movements as I knitted – but then that would become theatre performance, which I am not interested to do.

|

The multitude of gods and goddesses in India exists alongside significant traditions that emphasise abstract imagery and bring attention to light, fire, fragrance, sound and nothingness. Meditation or interiorisation is as valid a focus of reverence as the external image. Along the worship of images, there is an equally imperative (and enduring) history of Indian philosophy that abstains from representing and worshipping bodies. Nirguna, arupa and nirakara are only three of the commonly heard words that are used to describe an absolute: the formless nature of the divine, one that is, in the strictest sense, beyond the confines of matter, that which is beyond phenomenal properties or even psychological vagaries. What substitutes for the body in traditions that resist the depiction of bodily forms? Objects used in ritual, traces of the body or people’s possessions become relics that signify physical presence. Many believe that bodily forms must only be made by gods. Svayambhu forms (‘self-born’, naturally occurring) can thus become the focus of veneration. Palm prints and footprints recall the presence of a deity or person in many religions; and even the written word can become a talismanic protector or transformative force. Several substitutes for depicting actual images, thus survive. Importantly, then it prompts one to think: what is the status of the image that it is trying to substitute? And what, then, is the thinking behind nature or power of the body, if it can be so consistently substituted? The multitude of gods and goddesses in India exists alongside significant traditions that emphasise abstract imagery and bring attention to light, fire, fragrance, sound and nothingness. Meditation or interiorisation is as valid a focus of reverence as the external image. Along the worship of images, there is an equally imperative (and enduring) history of Indian philosophy that abstains from representing and worshipping bodies. Nirguna, arupa and nirakara are only three of the commonly heard words that are used to describe an absolute: the formless nature of the divine, one that is, in the strictest sense, beyond the confines of matter, that which is beyond phenomenal properties or even psychological vagaries. What substitutes for the body in traditions that resist the depiction of bodily forms? Objects used in ritual, traces of the body or people’s possessions become relics that signify physical presence. Many believe that bodily forms must only be made by gods. Svayambhu forms (‘self-born’, naturally occurring) can thus become the focus of veneration. Palm prints and footprints recall the presence of a deity or person in many religions; and even the written word can become a talismanic protector or transformative force. Several substitutes for depicting actual images, thus survive. Importantly, then it prompts one to think: what is the status of the image that it is trying to substitute? And what, then, is the thinking behind nature or power of the body, if it can be so consistently substituted?

In the rituals performed around the worship of mirrors in the Bhagavati temples of northern Kerala, we can see that they are very much treated like living icons. They are consecrated, periodically lustrated and worshipped in the sanctum of the temples. What makes these ‘mirrors’ all the more interesting is that sometimes these mirrors are not actually mirrors at all, they simply convey the idea of a mirror — they may be made of metal, but are non reflective. Sometimes, they are not even made of metal, but of stone. Yet, they are made to look like a val-kannati or a type of mirror that would commonly be used by people cosmetically: a round mirror with a narrow handle. Interestingly, the shape of the mirror is like the shape of a person — the rounded head sits atop the vertical leg-like handle. In some examples, the handle area is dressed in a dhoti, and small feet are carved at the base. The so-called mirror, is thus, actually, only mimetically communicating the idea of a mirror, the form of that mirror is mimetically echoing the form of a human figure and finally, the idea of a mirror itself is mimetically suggesting the concept that god is a mirror to the self without actually reflecting anything.

Sacred mirror, Northern Kerala, Aranamul region type, 18th-20th centuries; Bronze Collection of Ranvir Shah, Chennai

Aesthetic discourse on the idea of images employs Sanskrit terms such as pratima or arca, but the words we come across more frequently are pratika, pratibimba or bimba, which directly refer to the image as being a reflection. One of the earliest accounts of the importance of the mirror as a tool to a self-portrait, which is but a tool to self-awareness, is found in the Chandogya Upanisad. In it, Prajapati instructs Indra on how to distinguish his witness self (the real detached self which, according to the Natyasastra, is capable of aesthetic experience) from his bodily self, which is reflected in the eyes of others, in a mirror or in a bowl of water. On the one hand, a distinction is made: what is reflected is not the same as the reflection, and the perception of a reflection as the reflecting object is an error. Yet, on another level, in discussions of the nature of image-making and the nature of God’s body, the reflected body is considered to be the purest body conceivable. Indeed, some poetic passages on the reflected self suggest that it is only in reflection that the true, non-corporeal self may be captured.

Various artistic and ritualistic traditions illustrate this dual understanding. For instance, in those powerful forms of performance in which the performer and the audience are transported, or where the performer is possessed, the difference between reality and illusion becomes blurred. It is interesting to note that the process of becoming possessed and the process by which idols are said to become alive with the energy of the divine are similar. The process by which the performer is transformed into the deity in Theyyam, for instance, is complex. Certain rituals are performed after the performer applies sandalwood paste given by priests, as part of the deity, and through them, the performer is believed to sacrifice his ‘self’, and absorb the divine energy of the god who will perform. This is done by drawing in the energy of fire from a lamp (symbolising the prana, life-breath), consuming the food that is consecrated for the divinity, by receiving blood sacrifice, and by consuming liquor. The dancer then approaches the shrine and sings the tottam ( “to seem” or “to appear”) songs of the deity, which describe the god’s deeds, locate the myth of the deity in a geographic space, and describe in great detail the appearance and essence of the god, thus ritually indexing these as he becomes possessed. The song culminates with the dancer, who is now the divine body of the deity, accepting and looking into a mirror which is the final act in the realisation of possession. As the first performance ends, the theyyam blesses worshippers, accepts offerings and also settles disputes between them.

Similarly, a deity is invited into a new image in an elaborate ceremony of consecration or praṇa-pratistha, literally the emplacement, or stationing of living breath. Deities, as we know, embody objects other than images, such as pots, trees, footprints or, as we saw above, mirrors, for instance. Rituals of consecration include the appropriate making of the object or image that is to be possessed with divine energy, its purification, making sacred yantras demarcating sacred space into which the divine energy is invited (avahana), the filling of a pot with the energy, apart, of course, from the principles of nyasa, wherein every part of the body is prepared as a worthy receiver of the energy, and finally leading to caksu-dana, the gift of the eyes. While the prana-pratistha gives it life, the caksu-dana gives it visual perception. Once consecrated, the image (rather like the possessed body) is worthy of worship; and, equally important, after the period of worship, the spirit is asked to depart from the image, and it is surrendered back to nature through visarjan.

The final stage in embodying the deity in a Theyyam performance, Kerala, 2011 Photograph by Antony Kurtz

The act of witnessing one’s reflection at the moment of transformation breaks down the binaries between illusion/dream/image, and that which is real. From that moment the two states of being are united and the possessed body becomes capable of predicting and affecting cosmological change. Perhaps the most influential paradigm on idealised Indian images was first set up by Ananda Coomaraswamy. He explains that the concept of abhasa (‘shining back’, ‘reflection’, ‘semblance’ or ‘resplendence’) is built on the relationship of the individual self (jiva) with the universal Brahman. He further draws attention to the Vedanta Sutra, where Sankaracarya explains abhasa as a counter image or reflection. The true self ‘counter-sees’ itself, reflected in the possibilities of being the world picture (jagac-citra) painted by the self on the canvas of the self. The self, it is acknowledged, is a constantly changing entity, mirror-like, reflecting different realities. In very broad terms, two complementary histories inform modern Indian artistic imaginations of the divine body: one that celebrates the making of ritually charged, consecrated images; another that strives to show that the divine force cannot be shown embodied in the image of man. The two views although seemingly contrary, are in fact, complementary. Importantly, in acknowledging this illusory nature of life and of the world, the distinction between life and art is diminished, leaving us struggling to differentiate the real from the seemingly real. The words bhoga, lila and maya are three of several widely used terms, metonyms for the affectual and stereotypical view of how life can be experienced or lived within this world that is illusion.

The metal mirror for Bhagavatī before the ritual immersion Annur Pumalakkavu, Payyanur, Kerala Photograph by Balan Nambiar

The Advaita concept of mayavada rejects the duality between the real and unreal. The world of forms is seen as a manifestation and not an obscuration of eternal brahman. Mayavada rejects the distinction between a dreamlike state of imagining something to be true, and the wakeful state that purports to recognise the falsity of a dream. The multiplicity of forms of the world is a manifestation of brahman and is not separate from it. Several philosophical schools pick up on the idea of non-duality: Kashmir Saivism, for instance, propounds that Siva dwells in every being and form in the world, in all individuals as well as in the universe as a whole. Lila may be described as endless play, the eternal sport of the gods who manifest themselves in the world. The cosmic relationship between the brahman and manifest actions in the world is understood as lila. In non-dualistic philosophy, lila refers to the entire cosmos which comes into being as a result of the playful activities of eternal brahman. Art and experience form a bhoga, or the partaking of the lila. Do Pushpamala’s various embodiments, or if not that, then at least, counter reflections form a post-modern bhoga or a lila of sorts?

|

In my earlier avatar as a sculptor, I was well known for doing figurative work, which was quite performative and theatrical, really, and handcrafted, tactile. At the time, I was interested in creating an indigenous language to deal with the contemporary, inspired by Indian classical and folk sculpture and working with terracotta. I started moving away into making objects and minimalist installations in the early 1990s, responding to the events of the time. By the mid-nineties, I was feeling cornered, sensing that I was somehow whittling away my real (somewhat excessive and baroque!) self, when by chance I decided to do a photo-performance work for a group show on cinema, a jokey take on Fearless Nadia inspired by Bhupen Khakkar’s early catalogue photographs of himself as Superman. The initial shoot looked so interesting that I began developing it into a narrative, a photo-romance. This was a very different way of working, involving research, scripting, planning, collaborative production work and editing. A friend said what is interesting about my photo-performances is that I put myself in a set or location like a living sculpture, which is then photographed. While my earlier sculpture was very artisanal, my present work is conceptual, and what unites them is my interest in detail and craftsmanship. The ‘beauty’ lies in how they are put together and the ‘beauty’ or ‘gravitas’ of my physical self is in how it works within the frame, within what I am trying to say. While I am interested in the idea of visual pleasure, of ‘rasa’ or ‘juiciness’ – in making the images rich and sensual rather than bare and minimal – the layers of references from art and life, the theoretical underpinning of the work and the rigourous research behind it give it conceptual weight.

In my earlier avatar as a sculptor, I was well known for doing figurative work, which was quite performative and theatrical, really, and handcrafted, tactile. At the time, I was interested in creating an indigenous language to deal with the contemporary, inspired by Indian classical and folk sculpture and working with terracotta. I started moving away into making objects and minimalist installations in the early 1990s, responding to the events of the time. By the mid-nineties, I was feeling cornered, sensing that I was somehow whittling away my real (somewhat excessive and baroque!) self, when by chance I decided to do a photo-performance work for a group show on cinema, a jokey take on Fearless Nadia inspired by Bhupen Khakkar’s early catalogue photographs of himself as Superman. The initial shoot looked so interesting that I began developing it into a narrative, a photo-romance. This was a very different way of working, involving research, scripting, planning, collaborative production work and editing. A friend said what is interesting about my photo-performances is that I put myself in a set or location like a living sculpture, which is then photographed. While my earlier sculpture was very artisanal, my present work is conceptual, and what unites them is my interest in detail and craftsmanship. The ‘beauty’ lies in how they are put together and the ‘beauty’ or ‘gravitas’ of my physical self is in how it works within the frame, within what I am trying to say. While I am interested in the idea of visual pleasure, of ‘rasa’ or ‘juiciness’ – in making the images rich and sensual rather than bare and minimal – the layers of references from art and life, the theoretical underpinning of the work and the rigourous research behind it give it conceptual weight.

The multitude of gods and goddesses in India exists alongside significant traditions that emphasise abstract imagery and bring attention to light, fire, fragrance, sound and nothingness. Meditation or interiorisation is as valid a focus of reverence as the external image. Along the worship of images, there is an equally imperative (and enduring) history of Indian philosophy that abstains from representing and worshipping bodies. Nirguna, arupa and nirakara are only three of the commonly heard words that are used to describe an absolute: the formless nature of the divine, one that is, in the strictest sense, beyond the confines of matter, that which is beyond phenomenal properties or even psychological vagaries. What substitutes for the body in traditions that resist the depiction of bodily forms? Objects used in ritual, traces of the body or people’s possessions become relics that signify physical presence. Many believe that bodily forms must only be made by gods. Svayambhu forms (‘self-born’, naturally occurring) can thus become the focus of veneration. Palm prints and footprints recall the presence of a deity or person in many religions; and even the written word can become a talismanic protector or transformative force. Several substitutes for depicting actual images, thus survive. Importantly, then it prompts one to think: what is the status of the image that it is trying to substitute? And what, then, is the thinking behind nature or power of the body, if it can be so consistently substituted?

The multitude of gods and goddesses in India exists alongside significant traditions that emphasise abstract imagery and bring attention to light, fire, fragrance, sound and nothingness. Meditation or interiorisation is as valid a focus of reverence as the external image. Along the worship of images, there is an equally imperative (and enduring) history of Indian philosophy that abstains from representing and worshipping bodies. Nirguna, arupa and nirakara are only three of the commonly heard words that are used to describe an absolute: the formless nature of the divine, one that is, in the strictest sense, beyond the confines of matter, that which is beyond phenomenal properties or even psychological vagaries. What substitutes for the body in traditions that resist the depiction of bodily forms? Objects used in ritual, traces of the body or people’s possessions become relics that signify physical presence. Many believe that bodily forms must only be made by gods. Svayambhu forms (‘self-born’, naturally occurring) can thus become the focus of veneration. Palm prints and footprints recall the presence of a deity or person in many religions; and even the written word can become a talismanic protector or transformative force. Several substitutes for depicting actual images, thus survive. Importantly, then it prompts one to think: what is the status of the image that it is trying to substitute? And what, then, is the thinking behind nature or power of the body, if it can be so consistently substituted?