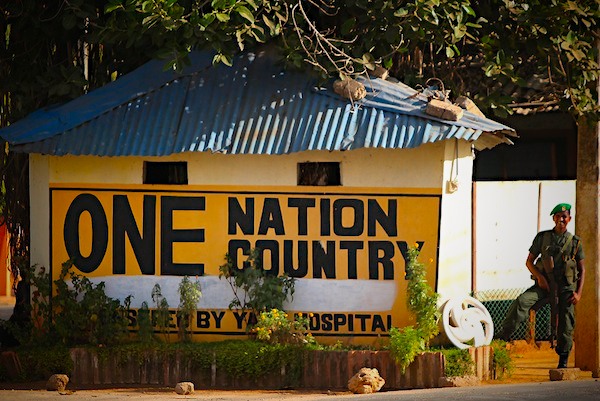

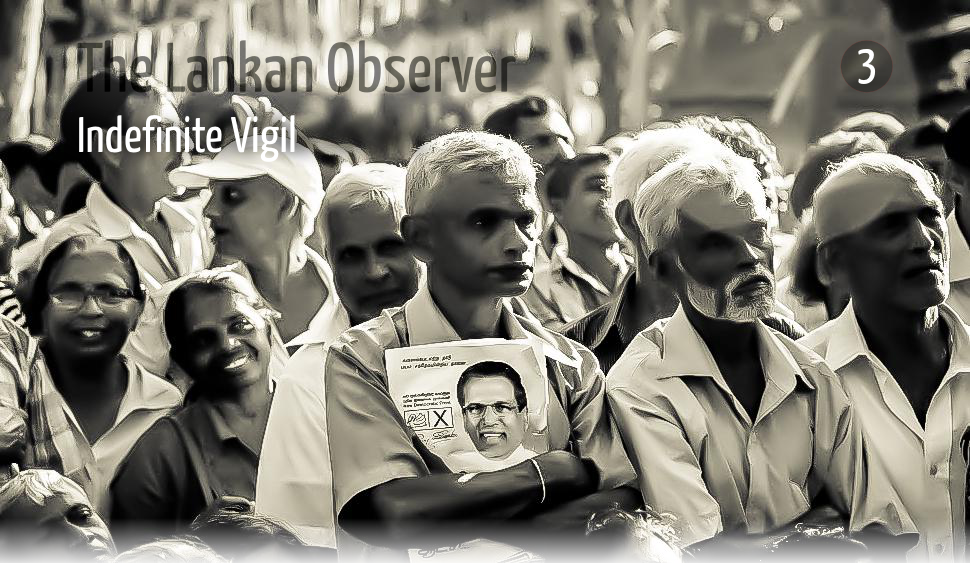

6 February 2015What a funny creature, democracy: dreamt of millennia back, fought for over centuries by the millions, never achieved, never complete, never granted. In place one day, gone the next. Conspicuously absent for a whole era, and suddenly back from the dead. Democracy plays with us, it provokes the degree of our determination. Democracy throws us in a transe, in a danse, a waltz – the waltz of democracy, at times soothing, often tragic. While democracy displays almost the exhaustive picture of its abuses in a State elections these days, a few miles down the map it brought relief to a nation. Sri Lanka just celebrated its 67th Independence Anniversary, and it did so, led by a new President, Maithripala Sirisena. A surprise, as Mahinda Rajapaksa himself, controversial President for a decade, called for these elections two years before the end of his term – the surviving trust of all the people was expected. The waltz of democracy is leading everyone, politicians, citizens, citizen-politicians. It acquires more momentum, sprouting Springs and alter-globalisations here, but also media propaganda and mono-identity fantasies there. How many successes of the democratic have been forgotten, losing their flavour of celebration behind all the ideological approximations and practical impatiences that democracy still seems to encourage? To continue a series of dialogues initiated last year, and to extend the always vital reflection, this week’s LILA Inter-actions welcomes Sasanka Perera and Thiranjala Weerasinghe. Sasanka Perera sides with the igniting energy of the felt political enthusiasm, but he also measures the real challenges facing Sirisena and each citizen to bring back balance and harmony. Thiranjala Weerasinghe analyses the party dynamics that led to the fall of Rajapaksa, and he looks forward to the shared efforts of a polity aware and energised to prolong the effort and the attention… since the dance is clearly not over. Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations. |

|||||||||

The Dawn of a New SensibilitySasanka Perera |

A New Era?Thiranjala Weerasinghe |

||||||||

Requested file could not be found (error code 404). Verify the file URL specified in the shortcode. |

Listen |

Listen |

Requested file could not be found (error code 404). Verify the file URL specified in the shortcode. |

||||||

|

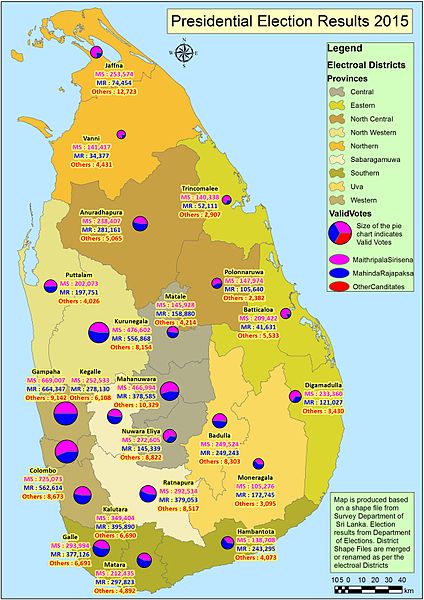

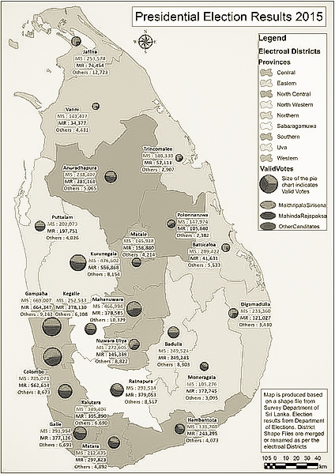

With apologies to Gabriel García Márquez, it appears that ‘The Autumn of the Patriarch’ has finally arrived in Sri Lankan politics since the presidential election, on 8th January 2015. But can it be truly a new beginning, in the context of which the country’s once-cherished but long-dismantled democratic traditions and institutions might be re-discovered? Or, would it be the beginning of a different kind of instability? Such questions seem relevant when one considers certain obvious realities. For instance, the former President, Mahinda Rajapaksa, presided over a despotic regime in every sense of the word, which brought into Sri Lankan politics practices of nepotism, widespread corruption, judicial tampering, political violence, misguided development, mismanaged interethnic relations and the dismantlement and undermining of democratic institutions as routine practices of governance. Despite this track record, Rajapaksa polled 47.58% of the total votes cast, as opposed to the 51.28% secured by the new President. In other words, an alarmingly high percentage of people were very supportive of the Rajapaksa regime, despite transforming the country into a veritable banana republic in exchange for a superficial sense of infrastructural ‘development’, of urban beautification and of postwar ‘security’. Clearly, despite the 91% literacy that the country had achieved by 2010, its political illiteracy was perhaps even higher. A tight battle

These negative indicators constituted the points of departure and the main rallying points for the campaign of the present President. However, given the reality of these numbers in political terms, the fulfillment of the far reaching political promises contained in the President’s ‘hundred day plan’ (including constitutional amendments for curbing presidential powers) as well as their entire political programme for the future, need to be addressed as a matter of considerable effort amid many challenges. Very clearly, it is not a leisurely walk in the park. In the midst of all this, there is a rather vocal demand for justice, spearheaded by both individuals and groups who made the victory of President Maithripala Sirsena possible. This hopeful but insistent political enthusiasm, and the sense of relief generally felt in the country is the most tangible general result of the presidential election. Many exiled journalists have already indicated their willingness to return to the country. The idea of ‘justice’ is articulated in different ways by different people. For many, it is a matter of reinstating the rule of law in the country and taking action against the individuals accused of corruption. The Janata Vimukti Peramuna (People’s Liberation Front) and many newly formed anti-corruption groups have already made a number of formal complaints to the country’s Bribery Commission, which had been visibly disempowered under Rajapaksa’s rule. The new government has requested the aid of the Financial Intelligence Unit of India in tracing millions of dollars of black-money believed to be stashed around the world by individuals linked to the former regime. The new Minister of External Affairs has formally requested the Criminal Investigations Department to investigate into the charge that the former President attempted to retain power by illegal means, when he realised that the results were not going his way. And these developments are under close and active public scrutiny. How to address the reconciliation?

On the other hand, despite signs of obvious infrastructural development in some parts of the former warzone undertaken by the previous regime, there is no denying that it has come without any sense of justice or reconciliation, after the depravities of the thirty-year civil war. These loftier ideals have been drowned by the post-war triumphalism promoted by the former government and readily consumed by many ordinary people in the Sinhala-south. Interestingly, people in predominantly Tamil areas of the northeast voted overwhelmingly in favour of the new President with no preconditions. While the new dispensation will not address the concerns of war crimes leveled against the military and members of the former regime via any international tribunal, the Minister of External Affairs has already articulated the need to address this issue through a credible internal mechanism. Besides, there are other ways in which issues of justice can and should be addressed. These include a speedier resettlement of the displaced people, the reallocation of the land acquired by the military during the civil war to their original owners and the provision of a political space for the Northern Provincial Council to function normally without undue military intervention. Soon after taking office, the new dispensation removed the governor of the Northern Province, a former military officer known for his obstructionist approach to the governance of postwar Northern Province, and has replaced him with a civilian, which has been welcomed by the Tamil National Alliance. Politically, this is a good sign, particularly when coming at a time when the new government itself, constituted of political formations with no collaborative history, still remains to be stabilised. It is also significant that the newly appointed Chief Justice and the Governor of the Central Bank are members of the minority Tamil community. In this overall context, patience, vigilance and public discourse are the key preoccupations to ensure that the government delivers on crucial national issues. Arjuna Mahendran, new Governor of the Central Bank, is Tamil

During his tenure, Rajapaksa increased the economic dependency of Sri Lanka on China, in addition to banking on the Chinese to deal with the thorny issues of international relations and diplomacy that Sri Lanka faced, as fallout of the destructive end of its civil war. This state of affairs played havoc with Sri Lanka’s preexisting and more cautious foreign policy, in the context of which the emotional makeup of the country’s diplomatic relations with India was one of the most visible casualties. It is very likely that the new government would review and redirect its foreign policy. It is not an accident that the first foreign visit Sri Lanka’s External Affairs Minister made was to New Delhi, soon to be followed by the new President’s first overseas visit, also to New Delhi in mid February. The strength of the President and the ‘national government’ he has helped form must necessarily come from the vigilance of the people. It was put in power by a coalition heavily supported by progressive artists, academics, civil society activists as well as people from different walks of life from across the country. These people and groups must remain the conscience of the presidency and the government if they are to realise the democratic principles which they expected the government to implement when they offered their unconditional support. What Sri Lanka has achieved is a fragile but much-needed democratic space. It is up to all sensible people in the country to ensure that this space is sustained in the long run. |

We Sri Lankans are living a moment in our history where we can be proud of the decision that a majority has made on 8 January, by sending a strong signal to all political leaders on the impossibility of taking their voters for a ride. Having been one of the oldest democracies in the region, Sri Lanka epitomised the maturity and strength of democratic institutions in sustaining core values even through an onslaught of authoritarianism, cronyism and abuse of power for nearly a decade (especially intensified since 2009). The brave initiatives of the civil society organisations and media institutions, refusing to be subdued by coercion, power and wealth, contributed to reinventing a democratic space and a hope for a plural society. For more than a decade, we witnessed the weakening of the opposition political front, as Mahinda Rajapaksa succeeded in dismantling the opposition camp through a number of coercive means. The in-party rivalries within the United National Party (UNP) and the crossovers of key political figures from the opposition – UNP, the communist party, Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, etc – to the ruling coalition had provided the Rajapaksa regime a 2/3 majority in the parliament. The military victory over the LTTE in 2009, the concomitant rise of Sinhala Buddhist nationalism, and the resurgence of ultra Buddhist groups like Bodu Bala Sena, with the tacit state sponsorship, not only alienated the minority groups from the mainstream political discourse, but reinvented the voter base of Rajapaksa among the majority Sinhala population. Although Rajapaksa was aware of the diminishing numbers of his voter base, vivid during the Uva provincial council election in 2014, the main opposition party, UNP, was also unable to muster greater support. It was this unique scenario, played out in 2014, that provided some confidence in calling for an early election, two years prior to the end of Rajapaksa’s term. However, the Ranil-Maithri-Chandrika pact, with support and influence from external elements, proved fatal to a regime that was over-confident in winning a third term. The Ranil-Maithri-Chandrika pact brought together

various strengths to defeat Rajapaksa The election of Sirisena as the President could mark both a continuation and a discontinuation of the Rajapaksa reign. As several analysts have pointed out, Sirisena shares much more commonalities with Rajapaksa than with either Ranil Wickremesinghe (Prime Minister in 1993-1994 and 2001-2004) or Chandrika Kumaratunga (President in 1994-2005). Both Sirisena and Rajapaksa share a common voter base, grounded (to a greater extent) on the Sinhala Buddhist nationalistic ideology, which is pronounced in different forms and shapes in several electorates across the island.

Sirisena was not only a confidant of Rajapaksa, entrusted with the responsibilities of Ministry of Defence in the latter’s absence during the last phase of the war in 2009, but also a veteran from the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), a common man who had risen from the lower ranks to what he is today. This unique position of Sirisena provides him with access into the voter base of Rajapaksa – an opportunity both Wickremesinghe and Kumaratunga do not enjoy. Given this background, the Maithri-Ranil combination, if it can be sustained, has the potency in playing a catalytic role in the country’s protracted ethnic conflict and mistrust. The removal of restrictions introduced for foreign nationals visiting north and the appointment of a civilian as the Governor of Northern province have also sparked lots of hope in this direction. The Anglo-American factors, having been part of the formation of the common candidate, already feel as an active component in the process and have shown their confidence in the current regime. The engagement of Jayantha Dhanapala, the President’s Senior Adviser on Foreign Relations, with the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Prince Zeid Ra’ad Zeid Al-Hussein, should lead towards Sri Lanka playing a more proactive role in the face of alleged war crimes during the last phase of the war and human rights violations since 2009. As it has been shown, Sirisena’s approach towards the neighbours, importantly India, will take a stark contrast to the one treaded by Rajapaksa during the last regime. Although it is almost only a month into the formation of the new government, people have witnessed tremendous changes in governance. The ceremonial retirement of Shirani Bandaranayake and the appointment of K Sripavan as the Chief Justice, relief brought in by the interim budget, investigation into several bribery and corruption cases where high-level politicians and government officials were involved, cutting costs and unnecessary government expenditure, have infused people with hope for a better future. However, it would be too much to expect concrete solutions to every single problem at this stage. Instead, we should work towards strengthening the basic fundamentals that have sustained the country through the authoritarian Rajapaksa regime. A new ‘Spring’?

I have heard several passing references made by the supporters of Rajapaksa to the Arab Spring and countries like Egypt, Yemen, Bahrain and Syria, to depict the kind of instability that can be destructive and detrimental to the well being of people. Such comparisons allude to the fact that a leadership under Sirisena could lead into instability and war. However, there was hardly any reference to Tunisia, a country successfully transited into a stable democracy. In my opinion, Tunisia had set in place, although feeble, a set of democratic institutions that refused to become the oppressors of its own people. Such a practice was absent in other Arab countries referred earlier and it has made all the difference. Undoubtedly what saved the country from the clutches of a dictator was this set of institutions and mechanisms that were in place. To a certain extent, they had provided independence from excessive political interferences, protecting the democratic rights of people and providing some faith in a system that has been rendered feeble through the years of oligarchic rule. It would be important to recall three instances to understand this issue:

The priority of all should be to exert tremendous pressure on the Government to fulfil its 100-day election promises leading up to the general elections in April 2015. This will create a system of governance based on democratic values and fair play. The political parties like the JVP and the Tamil National Alliance, along with academia, civil society organisations and the media, should sustain the level of critical engagement with the government we have witnessed during the last month. Moreover, most importantly, the public should be made aware of the fact that responsibilities in a democracy do not end with casting one’s vote but extend towards shaping and nurturing a public debate and discourse that ultimately provides directions for the government. |

||||||||

|

Sasanka Perera is Professor and Chair, Department of Sociology, and Dean, Faculty of Social Sciences, South Asian University, Delhi. At the University of Colombo for two decades, he has explored the connections of culture and politics in social theory, crossing the boundaries of sociology and anthropology. His articles and books have been extensively published, and he is also a writer, journalist and photography artist. He wrote this recent piece after the election of Sirisena, to whom he also sent a letter, published here.

|

Thiranjala Weerasinghe is a programme officer at the Regional Centre for Strategic Studies, Colombo, since September 2012. Prior to joining RCSS, he was a lecturer in Philosophy at the Ampitiya National Seminary (affiliated to Pontifical Urubaniana University), Kandy. Thiranjala has completed a Master of Arts in Philosophy from the Madras University, India. He is currently pursuing his LLB under the international programme of the University of London. His current research interests are rule of law, separation of powers and the surveillance laws of UK and its subsequent impact on human rights discourse.

|

||||||||

Disclaimers: The opinions expressed by the writers are their own. They do not represent their institutions’ view.

LILA Inter-actions will not be responsible for the views presented.

The images and the videos used are only intended to provide multiple perspectives on the fields under discussion.

Images and videos courtesy: Groundviews | உமாபதி | Groundviews | Adaderana | Colombo Telegraph | The Hindu

Voice courtesy: Shriyam Gupta

Share this debate… |

… follow LILA… |

||||