|

6 March 2015

Everyone for themself. Nearly one and a half century have clearly not been enough to prove Herbert Spencer wrong on his dark twisted fantasy. The latest Union Budget, for 2015-2016, shows how even the financial possibilities of a Union can facilitate the openly pro-business tastes of a government: sharply cut the funds planned for the social sector, claim a ‘democratic’ sharing of responsibilities, and demand of the States to now use their own Governments’ resources to try satisfying those programmes. New methods for old ideas: Holi inaugurates another refreshing spring of acche din… Survival of the fittest is thus still the melody for the underprivileged majority, but now the contagion has also reached State administrations, intra in their increased tensions with the communities, and inter, as a new level of competition will now rule over the mutual relations of the States. Visibly, more inequity is the only commonality evenly shared across the society and its structures, starting with our most fundamental social and cultural architecture. While most countries of the world will celebrate the International Women’s Day shortly, we are attempting a connection between the coincidences of this context, and look specifically at the effect of the new Union Budget on women. This week on LILA Inter-actions, K. Shanthi deciphers the technical details of the new Budget and shows how just letting the numbers speak already gives many hints. Ritu Dewan draws the multiple conclusions of the economic dependency expected of women, and she demonstrates how the Budget betrays the very ineffectiveness of the prevalent mantras of development.

Debate

Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations.

|

|

Over the years, efforts have been made to identify the thrust areas of our changing times and development scenarios, to shift budget allocations to be in tune with the overall situation of the economic policies. Deviations were noticeable when India switched over from mixed economy to market economy in the 1990s. But the present Budget is viewed as neoliberal, as most of the concessions relate to the corporate sector, and not to social sectors. This will have positive and negative implications from this. Foreign capital and corporate investment are sure to increase the level of production, the number and varieties of goods produced, and thus raise income levels and employment. But they will also perpetuate inequality, deprivation, which is sure to lead to social unrest. The country’s resources are likely to be exploited indiscriminately, endangering future growth. A well-regulated private sector is the need of the hour. This requires the working out of checks and balances, rules and regulations on the functioning of corporate enterprises, and this demands the necessary political will. At the same time, the middle-income category, the regular income earners, do not get any tax benefits. The programmes that cater to the need of the poor, especially the social security schemes, have witnessed a fall.

Before discussing any significant progressions in the conception of the Budgets across the years and decades, we should first acknowledge the fact that Budgets view women and children as recipients of benefit only. Women are not treated as participants and players in the development process. Women’s participation in the labour force, especially in the unorganised sector, had always been high. Of late, the entry of educated women into the labour force is also steeply on the increase. But budget allocations hardly address the needs and requirements of working women, including their safety. The need for creation of part-time jobs, flexible working hours, mainstreaming women who have given a break in their career, etc., have never found acceptance, neither in fund allocation nor in the design of welfare programmes. Though the concept of ‘gender budgeting’ has come to be accepted, its understanding and usage are still in the initial stages. There is drastic reduction in the present budget in the allocation of funds for women and children.

The Bharatiya Mahila Bank Fund

is one of casualties of this Budget

The allocation of funds for the category of the ‘hundred percent women specific programmes’ has fallen from Rs. 17,426.95 cr. in the 2014-15 Budget to Rs. 16,657.11 cr in the 2015-16 Budget – a reduction of Rs. 769.84 cr. The allocation towards women’s self-help groups development fund and equity capital to Bharatiya Mahila Bank Fund has been completely cut. The Rajiv Gandhi Scheme for Empowerment of Adolescent Girls (SABLA) has been drastically cut from Rs. 630 cr in the 2014-15 Budget to Rs. 10 cr in the 2015-16 Budget. While attention has been paid on the ‘safety of women’ (Nirbhaya fund), the empowerment of women is still not sufficiently addressed.

The budget provisions, both plan and non-plan, for schemes for the welfare of children, have been brought down from Rs. 69,888 cr. in 2014-15 to Rs. 57,919 cr. in 2015-16 – a fall of Rs. 11,969 cr. Later in the report, it is stated that in view of the enhanced devolution of Union taxes to States, as recommended by the Fourteenth Finance Commission (FFF), the plan outlay has been reduced and the States have to spend the shortfall of Rs. 11,969 cr. from the increased allocation under the FFF. The percentage share of the Budget for children has consistently fallen from 4.76% in 2012-13 to 3.26% in 2015-16. This is despite the fact that 39% of our population is made by the children of the 0-18 age group. Child health gets 0.13%, child development 0.51%, child education 2.58% and child protection 0.04%, with the total adding up to 3.26% of the total Budget of 2015-16.

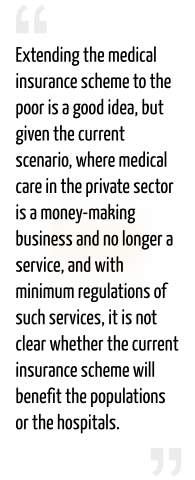

There are also certain silver linings in the Budget. These include the importance given to the promotion of infrastructural facilities, the unearthing of black money and the use of the same for developmental needs, the use of idle gold stock for development, training programmes for the rural youth, and the extension of medical insurance to the poor. But how useful these programmes are going to be, and how effective they will be in benefiting the common man very much depend on how they are going to be implemented. The infrastructure projects are likely to create large employment opportunities, apart from augmenting the capital assets of the economy. Training programmes for the youth is also likely to be a good initiative, given the fact that there is a mismatch between the quality of manpower and the skills required by the industrial/corporate sectors. But again, this needs to be planned properly, so that the question of ‘employability’ is paid due attention. Extending the medical insurance scheme to the poor is a good idea, but given the current scenario, where medical care in the private sector is a money-making business and no longer a service, and with minimum regulations of such services, it is not clear whether the current insurance scheme will benefit the populations or the hospitals.

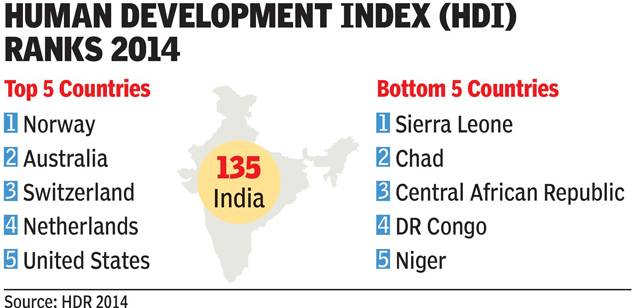

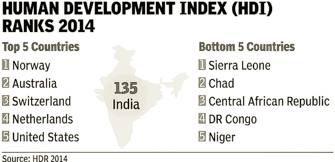

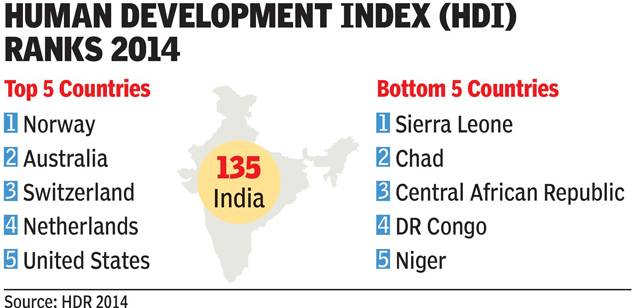

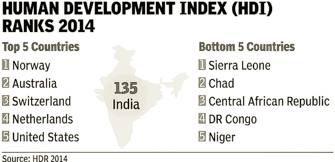

The HDI alone indicates the priorities

Given the fact that India is lagging behind in Human Development Index, women and child development is a must, and in such a context it is a pity that Budget expenditures are cut in these sectors, with the responsibility of allocations being shifted to the concerned State Governments. Infrastructure development, and sanitation programmes are sure to benefit the common man but only indirectly. Measures have been taken to plug the loopholes through Aadhar Card and direct transfers to bank accounts, but given the intra-household disparities in power sharing and access to resources whether women will enjoy their due share is highly doubtful. In the lower rung of the society, where in the majority of homes, men are alcoholic addicts, women bear the brunt of running the household. Invariably, the bank account is in the name of the male member, as he is the head of the household. Whether the subsidies extended meet his ‘personal’ needs or the ‘family needs’ is really a controversial issue. Since all policies, including budgetary provisions simply accept existing social norms and cultural practices as given and work on that, the desirable outcomes cannot be expected to be ‘gender just’.

|

The Budget is the single most crucial finance document of the year, which articulates in quantifiable terms the actual commitment of the State to its objectives, both stated and real. The Budget 2015-16 not only demystifies the thinking of the current Government, but also reinforces several fears that have been expressed in recent times relating to what needs to be done. The purpose here is not to romanticise the past or to demonise the present, but to examine what the Budget implies for the people, their economy, and their issues.

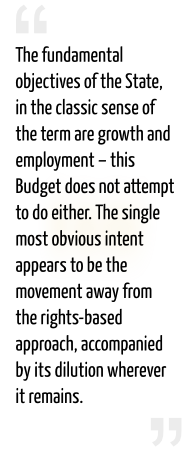

The fundamental objectives of the State, in the classic sense of the term are growth and employment – this Budget does not attempt to do either. The single most obvious intent appears to be the movement away from the rights-based approach, accompanied by its dilution wherever it remains. The single most crucial right – the Right to Work – has witnessed a series of reductionist measures in the recent past – its coverage has been consistently reduced; its basic character of being an employment programme is being ‘challenged’ by the argument that enough assets are created. The Rs. 5,000 cr. change in allocations over the last year does not even begin to make up for the rise in inflation. Similarly, various rights gained after several years of consistent struggle have been watered down.

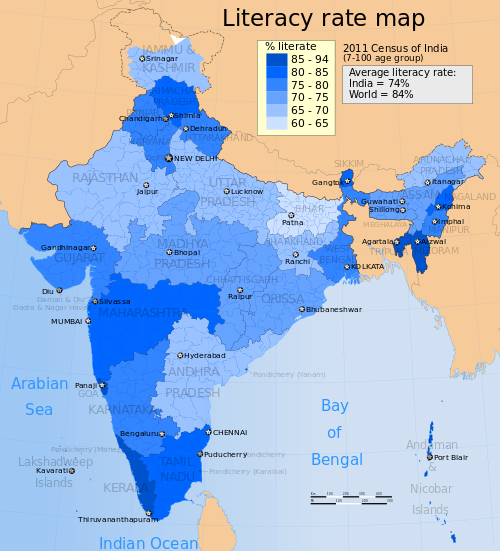

Literacy rates are still alarmingly low,

but education allocations have been drastically reduced

Among the most essential concerns to any nation is the quality of its labour-force as manifested in the most basic level of Literacy Rates. But the Right to Education has been virtually denied by the huge focus on IITs and IIMs, at the cost of Sarva Shikshan Abhiyaan, whose allocations have been reduced by a whopping Rs. 6,000 cr. – and this, in a nation that has among the lowest levels of literacy, with several excluded tribes reporting single-digit Female Literacy Rates. Allocations to the Ministry that implements the much-touted national campaign for a clean India have been halved from Rs. 12,107 cr. to Rs. 6,243 cr, though how this campaign can be isolated from the caste system begs for a deep re-think. The same holds true of the Health Ministry, whose allocations and importance in decreasing poverty levels have been continuously reduced over the last three months to stand at a pathetic Rs. 15,000 cr., that is, a mere Rs. 150 per year for an Indian citizen termed as poor. The Right to Housing, too, has been targeted with its allocation being decreased from an already low Rs. 16,000 cr. to not even Rs. 10,000 cr. What is indeed the biggest surprise is the shockingly paltry Rs. 94 cr. allocated for Panchayati Raj, even though the biggest focus in the last year has been Good Governance – an amount not even one-tenth of the Ganga Plan outlay.

Issues of Social Inclusion, too, appear to have no place in the Budget. The allocations for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are not even equal to half their share in population; 8% instead of 16.7% for the former, and barely 4% for the tribals, who constitute over 8% of India’s population.

The complete non-recognition of gender issues is rather unforgivable, as is the halving of the already low allocation to the Ministry of Women & Child Development, even though this ministry presents one of the best utilisation of funds for the last financial – around 88 percent.

It is internationally recognised that the agricultural and the rural sector are heavily feminised, providing livelihood to four-fifths of all working women in India. Yet, nowhere is this recognised: programmes such as MGNREGS, PMGSY, Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana are all ‘gender-less’. As is the fundamentally democratic issue of gendering governance, being given, along with with the Panchayati Raj institutions themselves, such short shrift.

No economic agency is ascribed to women, instead, they are stereotyped reproductive agents defined in the syndrome of patriarchal semantics; hence, the allocations to women and their tag-ons in budgetary terms – children, nutrition etc. The issue here is not to deny the importance and urgency of even higher funding for these sub-areas, but to highlight the independent economic, budgetary, fiscal and financial status of women.

Besides, the imperative of gendered financial inclusion has been totally negated. Gendered financial inclusion can be greatly enhanced by equilibrating financial and physical targets; this is especially important as women generally take small loans, and the fact that while physical targets may be filled, financial disbursements constitute an insignificant amount.

The small loans taken by many women

require specific budgetary responses

Individual taxation is preferred, because the economic benefit of working depends on how much a woman earns and not on her location in the patriarchal marital structure. The additional tax exemption to women was expected to be re-introduced in order to increase her incentive to take up employment and shift her labour supply curve. The Budget 2015 appears to have absolved the State of any responsibility whatsoever of incorporating employment in its current strategy by insisting that women undertake their economic empowerment through ‘assisted’ self-employment, while men do so by ‘skill’ enhancement.

A budgetary critique, to be relevant and true, must be located within the context of the paradigm within which the budget is perceived. If the mantra is ‘higher growth leading to inclusive and sustainable development’ and if it is only ‘growth that will lead to inclusive development’ then we need an urgent reminder that in the last few years in India, an 8% growth rate has led to less than 1% reduction in poverty.

|

|

K. Shanthi is the Honorary Director of Information, Documentation and Research Centre (IDRC) of the Indian Council for Child Welfare, Tamil Nadu. Formerly, she was Professor in the Department of Econometrics, University of Madras, Chennai and recipient of Fulbright Post-Doctoral Fellowship, Shastri Indo-Canadian Visiting Lectureship and UGC Visiting Professorship. Her fields of interest are development, gender and children’s issues. She has travelled widely, presenting papers in various national and international conferences.

|

|

Ritu Dewan is the President of the Indian Association of Women’s Studies, and Director, Centre for Development Research and Action, Mumbai. She was, till her recent retirement, the first-ever woman Director of the Department of Economics, University of Mumbai, and the founder-member of the first Centre of Gender Economics. She authored over a hundred publications encompassing a wide range of issues including Development Economics, Rural Development, Gender Economics, Infrastructure, Labour Markets, Environmental Displacement, Peace Studies, etc. Ritu Dewan has also been consultant for the Indian Planning Commission, the Ministry of Women and Child Development, the United Nations, and the International Labour Organization, among others. Her research focus is generally the result of the demands of several on-going movements.

|

|