|

20 March 2015

On the fast track, still, there are moments when an intimation or two arrive to remind us of how human language is closely involved in the design of our physical world. And one remembers some of the earliest narratives on nature, various creation myths from diverse communities. When did our language give rise to a gap in communication between the human world and the rest of nature’s creations? When did a radical opposition come in between our knowledge and our creativity as they figure in our universities, affecting our very mindsets? It seems it is no longer the Word that is first, but words. The words of our languages, deaf to one another. Today, the words of science should limit themselves to the knowledge born of objective observation, while those of poetry would not dare step out of the subjective beautification of emotions. It is long back, indeed, that poetry was wedded to science, and the couple has since seemingly fallen into a Platonic love-hate companionship, through the tempests and the deserts of those slow centuries. But the most familiar and once cherished symbols of our skies, sun and moon, reveal their dance, still, and align, like a few words becoming sentence and perhaps verse. Here is our chance to revive the youthful passion of the old couple. As the celestial event of a total solar eclipse meets the World Poetry Day in our calendars, scientist Gauhar Raza walks the memory lane, and tries to spot how the simultaneous growth of his two passions could only reveal their deep intimacy. Writer George Szirtes resorts to his quill, no, his keyboard, to muse over the new romance of the poet with science’s dearest offspring: technology. As techne gets smaller and smaller, inserting itself in our spaces and times, making becomes naming. New doors open for language and creation, but new challenges, too.

Debate

Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations.

|

|

I was born long ago in Allahabad, and since then, riding on this beautiful and delicate spaceship — ‘the Earth’ — I have gone around the sun 59 times. But, let me admit, by the time the realisation dawned on me that I was born, my parents had settled in the university town of Aligarh.

In the university campus, the school was almost next door, father taught there, and I started nagging my parents to go to school with elder siblings. Probably sick of daily cribbing, mother got me admitted to class one at the age of three. My first encounter with the explanation of a natural phenomenon was when I argued in the class how the steam particles that rise from my milk cups, every morning, go up in the sky, don’t like it there and catch cold, and due to fear, they hold hands, get converted into water and come down in the form of rain drops. I must have heard it from either my elder brother or someone else, but gave the story my words, which surely must have made it funny; the teacher could not control her laughter. The incident was reported to my father, and subsequently I was asked to repeat the performance at home and in school many a times. After that, I was constantly encouraged to ask questions and seek scientific explanations.

Thanks to my parents, we were never forced to memorise nursery rhymes. Instead, as we grew, quoting Urdu poets like Mir Taqi Mir, Mirza Ghalib, Mirza Muhammad Rafi Sauda, Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Sahir Ludhianvi, and many others became part of our daily conversation. By the time I reached standard eight, I had memorised hundreds of couplets of master poets and regularly participated in school competitions called ‘bait-bazi’, and was made president of both the science club and the literary society.

Sahir Ludhianvi

Scanning the past, I can say with certainty that besides the atmosphere at home and school, what attracted me most, as a child, towards science and poetry with equal force, were beauty, precision and the economy of words. Laws of motion, thermodynamics, or Bernoulli’s equation expressed in words or mathematical forms invoked the same feeling in me as a couplet from Ghalib’s collection or Rumi’s poetry would.

Much before reading CP Snow’s lectures on two cultures, I had realised that science, fine arts and literature, especially poetry, are the finest forms of human thought. Einstein once wrote “How can it be that mathematics, being after all a product of human thought which is independent of experience, is so admirably appropriate to the objects of reality?” I am sure that if the word ‘mathematics’ is replaced with ‘poetry’ the quote will remain as valid.

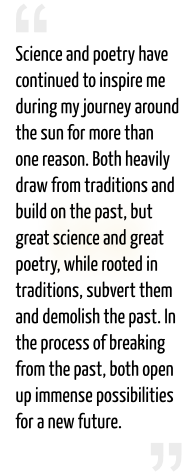

Science and poetry have continued to inspire me during my journey around the sun for more than one reason. Both heavily draw from traditions and build on the past, but great science and great poetry, while rooted in traditions, subvert them and demolish the past. In the process of breaking from the past, both open up immense possibilities for a new future. Both are revolutionary in nature. Kabir, Pushkin, Pablo Neruda, Newton, Darwin or Einstein, who existed in different times, changed the ways we relate to cosmic as well as social reality.

A major difference between the two, science and poetry, is as fascinating. In science, once the knowledge generated is absorbed, or when a paradigm shift takes place, the past becomes invalid or is subsumed into the present. Today, no one reads Principia Mathematica, which was considered to be the Bible of science at one point in its history. However, the poets of the past are read and sung even now and continue to inspire people to write.

The European enlightenment created compartmentalised disciplines within science, which accentuated the pace production of knowledge. The model of development also created a community of professional scientists all over the world. But this new model had no place for the professional poets. Institutions which supported them gradually withered away, but poetry survived. This forms a second major difference between the two. And moreover, the last two centuries have witnessed an increase in cultural distance between science and art in general, and between science and poetry in particular.

I am repeatedly asked two questions. “Why did you choose engineering as my professional career and not literature?” The simple answer is: I loved both, and while doing science, I could write poetry and sustain my life, but could not have done science if I had chosen poetry or literature as a profession. The second oft asked question is “How can you do science and also write poetry?” My standard answer is that both are creative fields, and if you have an average level of creativity, you can do both. Here, I am tempted to quote what Herbert Spencer had written in 1904:

The inability of a man of science to take the poetic view simply shows his mental limitation; as the mental limitation of a poet is shown by his inability to take the scientific view. The broader mind can take both.

Great minds transcend this cultural gap. For example, I find the best scientific definition of difference between life and death in the following couplet of Brij Nayaryan Chakbast:

Zidigi kya hai, anasir mein zahoor-e-tarteeb

Mauth kya hai, inheen ajza ka parishan hona

What is life, emergence of order in components,

what is death, disintegration of the same constituents

On the other end of the spectrum are scientists like Marie Curie, who said:

I am among those who think that science has great beauty. A scientist in his laboratory is not only a technician: he is also a child placed before natural phenomena which impress him like a fairy tale. We should not allow it to be believed that all scientific progress can be reduced to mechanisms, machines, gearings, even though such machinery has its own beauty.

The beauty that excites scientists is in abundance. The never ending cosmic fireworks, the dance of particles and antiparticles, the mysteries of biological evolution, the elusiveness of the Higgs boson particle, the haze that surrounds global warming, the double helix structure of life, the loneliness of planet earth, and many more thrilling occurrences stimulate creative thinking among scientists. A common person may not appreciate the beauty that excites a scientist because she has been removed from science, culturally.

The Higgs boson particle

Steven Weinberg in his celebrated book First Three Minutes wrote “The effort to understand the universe is one of the very few things that lifts human life above the level of farce, and gives it some of the grace of tragedy”. If the cultural distance between science and literature is reduced, both will be able to participate in this ‘tragedy’ and lift the human life to a higher level of existence.

|

The typewriter is a triumph of romantic mechanics. You can see precisely how it works. The levers are delicate yet strong. They rise and kick like a troupe of dancers. They are an army of spiders. You depress the keys and they snap against the ribbon. Typebar, spool, platen, carriage, shift key. You can see and name each part, each name memorable, ceremonial, utopian.

The older the typewriter the more it conjures the future. Typerwriters were Captain Nemo’s submarine. Some looked like navigation aids, some like musical instruments, some like glorious hats, some like a baroque stage. There would be no more scriveners, no more laborious longhand. Everything would be short, sharp and spiky.

There would also be drudges located in vast typing pools, standard desks, their human fingers moving as on a depressed mechanical piano. My stepmother was a secretary all her life, but when she stopped, she developed acute arthritis. Her fingers were twisted out of shape and caused her agonies. She had to have pins inserted into them. She was not working the machines: the machine worked her. She was the machine, her fingers an extension of the typebars and levers, her mind a transmitting device for the altogether bigger machine of business.

I was learning piano. Each depressed key moved a lever that moved a hammer that struck a wire. In front of me lay an open book with notations. Someone had produced the notations: the notation produced the music. Between the two, fingers and levers in motion.

❦

At junior school we were taught handwriting. It started with forming the letters, now capitals, now lower case. We had exercise books covered in blue sugar paper carrying a label with our names and class and subject on. The pages were lined so we knew how high our letters should be. In the borders we drew decorative tulip shapes. There were right and wrong ways of drawing the tulip or forming the letter. There were strict standards. There were pens and pencils that made marks. We had shoulders, arms, elbows, wrists and fingers that laboured at standards. We leaned into our work, pursed our lips, were clumsy or graceful within the terms of grace, according to the standard.

Later it was expected that our writing should develop personal traits representing aspects of our character. Writing was character forming. We formed characters. The characters formed us. One person had ‘an elegant hand’, another’s hand sprawled and scratched and stumbled. We laboured at our selves. Some drew tiny circles instead of dots above the letter i. Some i’s were lost in an onrush of other lower case characters, the n’s the u’s, the m’s the, w’s, all running into each other, their soft curves merging into an undifferentiated stream.

❦

Some nights, I wake at inconvenient hours and cannot sleep. I lie and stare at the ceiling for a while, turn this way and that, and in that condition of waking consciousness, words and lines occur to me. They begin to fascinate me. I want to see where they go. I reach for my smartphone and begin to write. I do so in the 140-character format dictated by Twitter. I use one finger only but have become quite adept at this. I don’t wake my wife. The light on the phone is as low as it can go. The brevity of the form offers certain possibilities. There are epigrams, gnomisms, propositions, and proverbs and jokes and remarks and snatches of verse and fragments of stories. There are forms that are self-contained but can lead on to another in a chain. Small islands become archipelagoes of language that extend into the night.

The keyboard is silent: the texts I type move out into silence. There is no visible mechanism but there are metaphors. The space the texts enter is a rapidly flowing river that contains other words, other images, other brevities. It is time by other means. The silent voices rush past me and swirl away, their very ephemerality a nagging reminder of my own mortality. We don’t see everything in the stream, only the parts we have shown some interest in, but that interest is necessarily fractured and dreamlike, sleepless and associative. Laughter, curses, cries, enigmas move in it. I see them: they see me.

I see them seeing me as I write but I cannot quite picture them. In perfect loneliness, in the middle of what is night for me, they constitute a semi-conscious audience before whom my words and lines perform, then vanish. The virtual reality of the waking self is the condition the text lives in. It is, I sometimes think, the condition of language itself, a floating, a white noise becoming briefly articulate. Then fading into silence.

The discourse of poetry is not entirely logical, not quite lodged in the construction it modifies on entry. Keyboard, laptop, instantaneous conjurations of presence, raise houses and cities and ghost their way through the great conurbations of the imagination.

❦

The fantastical typewriters, the armies of drudges at their machines, the mechanical pianos with their mechanical fingers, are part of a process whereby notations produce notations. The term technology is derived from the Greek techne, meaning craft or art. Techne is also a form of practical epistemology. Our technologies hover between naming and making. The world is faster, more instantaneous, more present-yet-absent, more present-in-absence. Our hardware is ever slimmer, ever more on the point of disappearing. From a roomful of machines, to a desktop, to a laptop, to a small phone, to a pair of glasses it moves towards vanishing.

We are ghosts in a machine that is itself becoming ever more ghostlike. The real world abides as an intractable form of organic hardware. Outside are leaves and pavements and hands and earth. There are events that move through us the way a ghost moves through walls. The mechanics are invisible. Explosions slice through us: we carry them in our hands.

|