|

24 April 2015

Feminine, masculine: perhaps the first and most defining difference that we ever knew. We have had thousands of years, and thousands of cultural lineages, to reinvent our perception and our practice of gender. And yet, our societal debates, seemingly pluralistic, often snake between the poles of culture- and modernity-centric binaries. Like the blinkers of a yearling, we limit the scope of spatial and temporal alternatives in our craving for the next instant of life, of political renewal, of social change. We worry: where could we go, indeed, if we left ourselves be pulled by all the directions that a truly limit-less enquiry on gender may bring? A fallacy, as forces always combine, perhaps imposing a more nuanced pace, but also a more sustainable movement… At which level are we pitching our discussions of gender? Caught between Nirbhaya and Vogue’s Padukone, between India’s Daughter and the daily news items, are we not running out of breath, first of all, strangled between the urgent need to respond to immediate events, and the collective necessity of addressing the deep roots of this matrix of words and gestures, so to transform it profoundly, too? The individual may lose touch with the universal, and cynicism becomes an everyday temptation, as our environment reminds of the interval still separating each of us from this culture all of us share. But it all starts with an individual – a single moment, a feeling, an idea, a body, a voice standing from the quicksand of appearances to recall: change starts here. For this 65th and last weekly edition of our medium, indeed bridging inter- and actions, Maya Krishna Rao and Jasmine Lovely George present two initiatives aiming at exploring our assumptions behind gender. Through performance, and through sex positive, constraints become empowerment, and prejudices, potentials. The smooth lines of our mental and embodied borders start quivering. Look closely… can you still see them?Debate

Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations.

|

|

[Reported conversation] Back in 1978-1979, we were beginning to read cases in the newspaper of dowry deaths. As a woman, I was getting very disturbed. One day, I got a call from a women’s organisation, asking me to make a play with my actors, to raise these issues. I accepted the offer, but I had no actors and this led to the beginning of a long journey for me: I responded that the women themselves would need to be the actors. For the play to become a vehicle for discussion, they had to carry it. Thus Om Swaha happened.

These women worked towards using art – theatre – to rethink who they were and what their attitudes were. In the morning, we did theatre exercises and for some of them, this was the first time they were seeing and sensing their own body. When it came to giving a ‘message’, it was not difficult to come to what to say about dowry. But, as it turned out, talking about dowry was only a stepping-stone to facing larger questions. Discussions revealed how women’s organisations did not have one particular identity: each woman had a different outlook. And improvisation in theatre sometimes challenges narrow, fixed notions. Supposing you are improvising the mother-in-law’s role today, you have to ‘live’ her. You become a person, rather than ‘mother–in-law’. The finer details come out – in playing out the little moments, she stops being black and white; it is not about pasting issues onto some actors, but about drawing the audience into thinking around these issues. If you want to engage an audience, you must show the multiplicity of moments and issues playing out in a single situation.

Maya Krishna Rao in HAND OVER FIST

In 2007, the United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) asked me to prepare a show around ‘masculinities’. For the longest time, the word I had stayed away from was: agitprop. Terms like ‘masculinity’ or even ‘dowry’ are already very loaded, so they activate in me a ‘warning signal’… But finally I took up the offer and worked with my two colleagues, a sound and video designer – both males – on the piece, HAND OVER FIST. I would dialogue with them, on what it was like for them, growing up as a boy… and slowly I realised masculinity was like a river that floats in and out of all of us, men and women. To be able to touch it, to catch it: that was the challenge. We made an episodic show: I would, through improvisation, try to identify a moment of masculinity as it plays out in life, as it manifests here, or there… In its final form, the show was not trying to say any one thing, but rather, worked like a prism – it sparked off many moments, diverse and incomplete.

The play was also about me taking on a male role for a moment – wearing a man’s coat – but not becoming a man fully. Friends have told me that I often look androgynous on stage. I may get this from my long practice of Kathakali. In a form like Kathakali, you learn to train the flow of energy. You can push it in a specific way, almost explicitly in a masculine way… but it is always in your hands, where you want to take it.

Through the decades, we all changed as performers, but some issues remained. This came to me recently when I made WALK. In 1980, we made the street play, Dafa no. 180 about the law on rape. More than thirty years later, the Delhi gang rape happened. The public response was different. In a way, it was like a performance – for two weeks, public spaces were taken up with young people walking, everyday. So, in creating WALK, it seemed to be part of a continuum in life, more than a performance.

Women at Rashtrapati Bhavan

The whole intuition of WALK came in one hour, after some organisers from JNU asked me to prepare a performance for the next day. That was the strength of what was happening, out there, in the world. I did the piece at other places too. As new things would come and inspire me, the piece slowly evolved. When came the time of Section 377, a line came to me: “Nobody taught me how to walk. So why would anyone teach me where to walk? What to wear when I walk? Who I meet when I walk?” It also meant: my head did not tell me how to walk. My body taught me how to walk, and it is because I know how to walk that I know what freedom is. As I teach engineering students, life sciences, computer science students now, this comes up again: these boys and girls do not know where their bodies are; they come with their heavy head and their bodies, as if being dragged, a mile behind them… They do exercises where they are simply sensing their own body; it seems as if their own bodies are getting mirrored as they watch others move – that is such a high. Or, like in another workshop, getting a bunch of girls just to lie on the ground and roll on top of each other. In the beginning, everybody just giggled, no one had ever done it before, and they got rid of their dupattas… but then, how easily and quickly 19-20 became 6 year-olds again. The body had not forgotten how to have fun.

Some lines of WALK have changed. In initial performances, I said: “If a man doesn’t know to ask before he has sex tonight, don’t walk with him, I’ll walk with you…” Soon after the bus gang rape, we were angry. It felt like we needed to speak our mind – the words came as a response to a horrific event. And so did those particular lines. But since then, there has been a shift – the idea of ‘consent’ has taken a central place in Walk. Not simply building consent with another person but consent with oneself. I play with the idea of personal space: “Can you see… that I may draw my line here, but cross it just for today… but I may draw it there tomorrow… will you see it, will you know it…?” What I want to ask is whether we can go into the zone where we are not talking, where we are just being, sensing each other, through our bodies. Whether we can bring up our boys to see and know a ‘no’ without having to hear it. Performance empowers not just through my practice as a performer, but also through learning to read the signals that you give me as audience. Being able to read signals of the other makes me who I am, who I become. And this goes into territories other than gender: to culture, religion, etc.

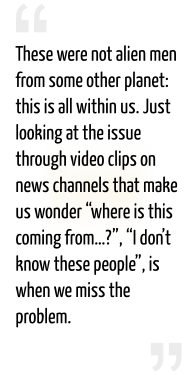

Wondering whether Walk was incomplete, I did an exercise one day: trying to get into the skin of one of the rapists, in the bus. As an artist, I knew this was possible. That he was a man, a rapist, a murderer makes it difficult, but not impossible. While I was sitting, still, with eyes shut, my body first got into gentle motion, rocking: the moving bus. Imagining the four men around… and the woman lying there. And then the picking up of objects and shoving them into her… Just as actions… Actors know action. Trying to live through these actions made me think: it is possible to do such actions. It seemed they came from a very dark space of deep despair – a despair we all know, which we have all experienced at some point in our lives, maybe differently. But for these men, because of the nature of their lives, the sheer repetition of aggression in one form or another, the despair becomes a pattern, and you then practice your despair – it comes out. Maybe you watch aggressive pornography day after day, and so much aggression gets built in that, and it becomes easy to pick up something and do these acts. Not that I could see myself doing it, but I could see that it was possible. These were not alien men from some other planet: this is all within us. Just looking at the issue through video clips on news channels that make us wonder “where is this coming from…?”, “I don’t know these people”, is when we miss the problem.

All this has made me turn to education – school education – where drama should not deal with gender alone. Gender must be dealt with as mixed with everything else – once in a while, picked out and looked at separately, but then put back along with everything else in life…

This text is a reported conversation

with Samuel Buchoul

for LILA Inter-actions

|

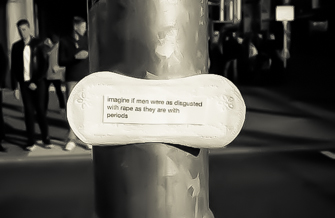

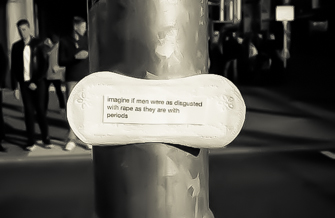

In the last few decades, mainstream feminism/s has worked with state machineries in changing the conditions of women in the society. In developing countries like India, gender equality has been incorporated in tenets of our Constitution, which has been played out in the form of schemes focusing on gender. Post the Nirbhaya incident in Delhi, 2012, it is interesting to note that the slogans were around asserting sexual rights, and claiming the spaces as sexual beings. While, on the one side, the right wing conservative parties rallied for the protection of women, the young feminists fought for the sexual autonomy of women. These demands around sexual autonomy culminated into campaigns such as ‘Take back the nights’, where women stayed on the streets the whole night, ‘Kiss of love’, where women came out in huge numbers to assert their right to chose partners, and ‘Pads against sexism’ where women demanded of the state to provide free pads for women. There is an increase in the demands surrounding sexual rights in feminism/s, and in particular campaigns focusing on the body. Be it the ‘Pads against sexism ‘ campaign, or the ‘Kiss of Love’, there seems to be a direct confrontation with the authorities, and it has re-opened the spaces within the feminist circles to reassess their relevance and also their fault lines. These campaigns brought terms like ‘pads’ and ‘kiss’ in the public domain, and we could feel their presence both in offline and online spaces.

The ‘Pads against sexism’ campaign

The safety model has been one of the products of the post Nirbhaya movement, where feminists demanded state accountability in terms of providing safety for women in public as well as private spaces. The requests were to make spaces more accessible, as opposed to creating a safety net around some spaces. Feminists like Nivedita Menon and Shilpa Phadke, through their academic work, rejected the concept of protectionism, and instead echoed the need to loiter and reclaim public spaces. However, the state reacted in the manner of a patriarch who understands women as subjects that need protection. While women were busy celebrating their victories on the streets, the state co-opted the theme of sexual autonomy and produced a protectionist mechanism by mooting for surveillance and CCTV cameras. Every demand of agency has been neatly packed into a bundle of security measures, which has just re-enforced the idea of the gendered being, without providing any agency.

The state’s relationship with sexuality is rooted in the violence framework, which has always perceived women as the victims of the act of sexual violence. The state perceives women as gendered beings with roles limited to the reproductive functions and in the familial scenarios, without ascribing any sexual agency to them. This brings the attention on sexual violence, and thus this discourse has also completely removed spaces for any discussion around sexual pleasure. This also makes it difficult for the state to deal with any demands around sexual autonomy. It perpetuates a certain ‘sex negativity’ in general, which gets combined with the belief that women, in particular, are passive sexual beings.

Sex positive is a discourse that takes the discussion away from violence and tries to value the pleasure one receives from the act of sex. Sex positive tries to value the body as a positive experience, and it welcomes narratives outside the violence framework, providing an alternative to the patriarchal understanding of gender and sexuality.

In one of the sex positive workshops I conducted in Delhi, there has been a realisation that there is a lack of language around sexual pleasure. There is a biological understanding of genital and reproductive organs, but the lens employed to understand these organs and their roles, is sex negative. The dearth of sex positive discussions leads to a thorough denial of female sexuality, while the prevalence of violence is completely re-enforcing the patriarchal understanding of sexuality. The results of this lack of language are the reactionary/confrontational campaigns that seem to be responding to already existing mechanisms. For example, the ‘shame the rapist’ campaign was in direct response to the society’s attitude towards the survivors of rape. These are all questioning sex negativity, and more precisely, the disgust for women’s sexual autonomy, but they do not provide an alternative to this existing negativity. All discussions around sex have been reduced to the question of freedom from violence.

Feminism also struggles with its relationship with sex positive discourse. While movements around sex workers rights, and work around sexuality and disability have been able to introduce an element of sex positivity, the inherent discourse in the work has mostly been around sex negativity.

‘Feminist’ discourses in the market…

Feminism/s, in the recent years, has become one of the most contested movements. Lately, the principles of feminism have been co-opted by a number of entities, which has led to rather confusing results. From Vogue Empower with their latest series of videos around gender equality, to Ariel asking men to share the load in washing clothes, the focus has shifted to a consumer, which is being created in the marketing campaigns of these capitalist companies. Neo-liberal policies seem to be providing more freedom to a woman in terms of access to things, while creating a new buyer in the process. The My Choice video by Vogue focuses primarily on the demands and needs of a woman based within this consumerist culture. The appropriation of feminist principles by both state and capitalist ventures has also resulted in a conglomeration of results which is devoid of any understanding of the intersectionality prevalent within these principles. The My Choice video completely missed out the class analysis, where choice is shown in a vacuum, without providing any understanding around the term ‘choice’ itself. On the government’s side, the appropriation is also repeating a certain ideology. The Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao schemes provided by the state plays on the gender stereotype of an educated girl who can take care of her family better.

Rights! Right?

There is a demand to be seen, to be counted, and to be celebrated within the consumer culture by women themselves. We are at an interesting juncture, where neo-liberal policies are being seen as the new champions of women’s rights, with feminism/s being accused for not using this opportunity. It also leads to interesting reflections for feminism/s, if it needs to revive the dialogue within a sex positive discourse itself. Can feminism, as a movement, stand alone, stay outside of these institutions which play an important role in the lives of the individuals? It is important to engage with these institutions when feminist principles are being used, and hold these institutions accountable for every usage of these terms. The campaigns happening on the streets and in the virtual world in terms of protests have been effective in at least showing the discontentment feminists have felt about the misuse of some of the feminist principles. However, there is a need to bring these discussions together, and to revive the voice of the movement, to ensure that the younger lot of the feminist movement is also part of this process, where neo-liberal rights over one’s body is critically examined without dismissing the capacity of the individual to enjoy these rights. Feminism needs to re-define its relationship with both the state and neo-liberal policies in a much more effective manner.

|