I had recently graduated from the tenth grade when my family decided to move to a satellite city of Delhi, about an hour away from my school. To avoid the daily arduous travel, I started attending another school much closer to my new home. This was a fairly new institution at the time, and my batch was the first to graduate from there. Being the torchbearers for its educational enterprise, we also became one of the most closely monitored groups of students at school. We were not allowed to go outside during recess lest we got tummy ache from running around after eating, or a sunstroke from the heat. Boys and girls were not allowed to play together because one day an employee of the school had spotted a girl with her arm on the shoulder of a boy during a basketball game. That let many administrators’ imagination run wild about what these devious children might be up to when the sagacious adults were not looking. To add to that, the infrastructure of the school didn’t help either, as the windows of all classrooms had to remain shut at all times to ensure the effectiveness of the air-conditioning system. I doubt those windows were ever even designed to open at all. This was in stark contrast to my previous school, where students sometimes took the liberty of quietly jumping out of the window and into the playground if the lectures got too boring. In the name of safety and comfort (and also a sprinkle of privileged pampering), this new school sealed its students up inside the panoptical building, where we would have to obediently follow the established rules and regulations. A space that was meant to ignite young minds, nurture curiosity, and inspire the search for answers ironically created a space of rigid control instead. Sometimes, some of us managed to find and exert our agency by either secretly flouting rules, or finding alternatives to the activities that were banned. But I always wondered the impact such a system would have on the younger students who were growing up under such authoritarian scrutiny, without any exposure to a free learning space.

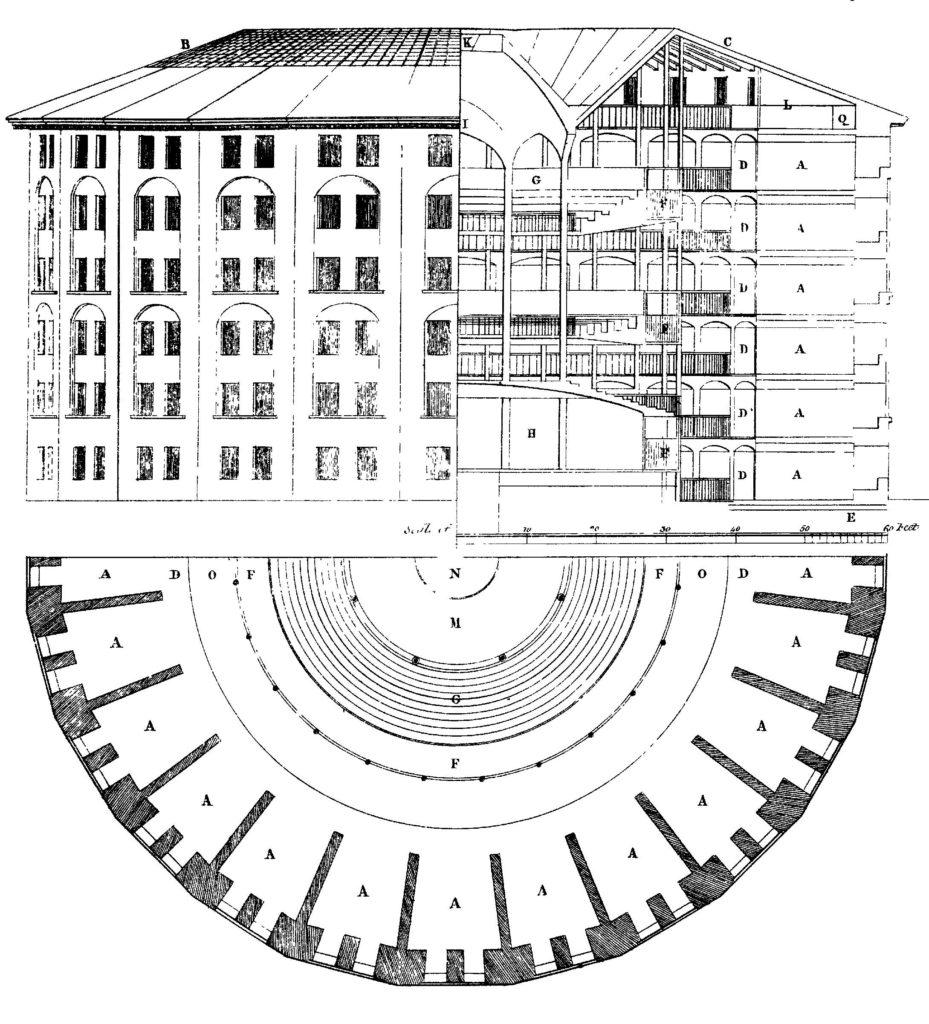

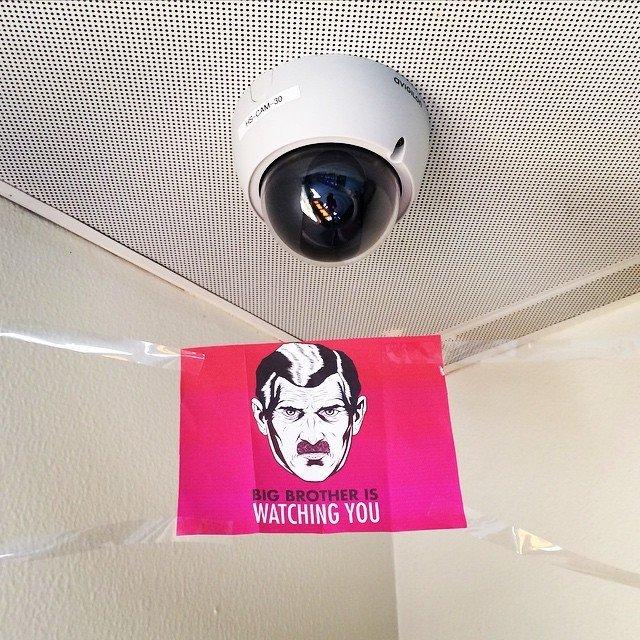

These questions come back to haunt me today, as Delhi schools seem to be morphing into technology-driven versions of Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon. The state government’s plan to install CCTV cameras across the city has finally been set in motion, with close to 4,000 cameras being installed across 388 primary schools run by the South Delhi Municipal Corporation just this summer. Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal also announced the installation of a total of 150,000 cameras across school campuses in the city by November. This in and of itself sounds like a prudent plan by the government, considering law enforcement agencies do not fall under its jurisdiction in the city. Add to that the rising cases of violence, abuse and bullying that are reported in schools these days, it is no wonder the government is desperately trying to get the situation under control. On the other hand, CCTVs are a great way to monitor and record incidents, help solve crimes, and even have the potential to alert authorities for prompt action – we are already seeing something like this come up in China, where facial recognition cameras have been installed inside classrooms to detect a student’s mood in real time; they are now adapting this in America to monitor cases of student violence. But, I wonder, in taking such measures, are we approaching the issue of law and order in schools from the right direction? The classroom is as much a private space for children, as our bedrooms or houses are for us. Would we be okay installing cameras all over the house, with access to law enforcement agencies at all time, if incidents of break-ins or robbery in our neighbourhood suddenly shot up?

The more dystopian our solutions start to sound, the more worried we should be. For instance, a look at the implementation and acceptance of this scheme in Delhi schools so far would make anyone pause and consider the move. “We sometimes scare the students by telling them that there are cameras watching them…” a report in the Hindu newspaper quoted a principal from one such school as saying. “…They become alert after that… at least for a while, then they go back to being themselves,” he continued to say. Many teachers supported this view, saying the cameras had been helpful in monitoring students and keeping them in line. The same report asked a parent whether he was worried about the privacy of his child following the government’s proposal to share live feed from these cameras with the parents of all pupils. The father responded, “They are little kids, what privacy do they need?”

I was shocked. Not only by the comments made by such important mentors in a child’s life, but also the casual way in which they were presented in the news story. Are we really so comfortable treating children as passive, subordinate receivers of our policies? How far are we willing to compromise their sense of freedom in the name of security? But more importantly, how much do we really understand about children and their psychology, to be able to assess the impact of such surveillance and technology on their lives? A look at some seminal ideas from the field of child psychology and cognitive development may help uncover some answers.

The idea that a child’s cognitive capabilities were different from that of an adult was first observed in 1920s and 1930s. Before this, children were largely seen as miniature versions of adults with lower intelligence. However while marking intelligence tests for children for a project, psychologist Jean Piaget noticed that all of them consistently made the same kind of mistakes. He saw this as an indication that they all thought similarly, but in a manner that was different from adults. It wasn’t that they were all less intelligent, but maybe their cognitive processes were just different from that of adults. This hypothesis led him on his path-breaking study of problem solving and social interaction among children that eventually gave us the theory of cognitive development that we know today.

Around the same time, another psychologist, Lev Vyogotsky, was conducting his own research on cognitive development among children. There was one key difference, however, that his research revealed. Piaget’s model was universalistic, in that he assumed it to be true for all children everywhere. Also, the development according to Piaget was completely biological, with hardly any participation of the child or her social and cultural context. Vyogotsky, however, proposed that the child actively noticed the socio-cultural systems, concepts and objects around her, and appropritated them to build her own meanings. Her cognitive development, therefore, was highly specific to the socio-cultural influences in her life, and could vary across cultures. We see this, for instance, in the Buddhist conception of a child, where they are often seen as the reincarnation of enlightened monks and lamas. This is why in 1936, a two-year-old child was declared to be the most important person in their community, after he was identified as the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama. Precocity, therefore, becomes an important characteristic in the Buddhist community, allowing a young individual to be seen as more than just a “little child.”

Numerous psychological experiments and theories over the years have elucidated that one’s self-image is heavily dependent on external factors. In fact, the father of individual psychology, Alfred Adler, theorised that a child’s attempt to compensate for or avoid feelings of inferiority guides much of her personality development through the years.

So, if we place such a child under constant surveillance aimed at control, what do we imagine the outcome to be? Krishna Kumar, educationist and former Director of NCERT, eloquently presented this argument in an article sometime back: “…think about the meaning of growing up and learning under the shining eyes of a CCTV. Parents are watching you in real time. They watch you as you hesitatingly stand up and try to answer a question the teacher has asked. They watch you as you whisper in your deskmate’s ear. You go home and the parents ask you why you didn’t know the right answer, why you talk in class, and so on. You don’t know where to hide, what to do to save your limited, fragile honour.”

Now, children may not always be this fragile, or parents always this intrusive. But if already the norm is for the majority of the class to remain unengaged or shy, how do we expect the voyeuristic classroom to make learning any better?

There is an interesting experiment that was conducted by David C. Glass and Jerome E. Singer in 1972, where they asked two groups of people to solve certain problems while loud, harsh noices intermittently played in the background. The first group was given a button that would stop the noise temporarily, but they were asked to use it only if they absolutely needed to. The second group was given no such button. The results came in, and the first group (with the button) performed significantly better than the second. However, they never used it. It seems that just knowing that they had the button, and by extension some control over a stressful situation, helped them do a better job, even as the sensory experience of both groups remained the same. Many such experiments have been conducted since that reify the lessons Glass and Singer drew.

If we are to truly improve and transform our educational institutions and practices, creating tyrannical systems will not help. What is needed instead (as it always is) is more control in the hands of all stakeholders of the system, especially the teachers and students.

You may also like

2 thoughts on “Counter-Productive Measures: To See Or To Let Be?”

Comments are closed.

Maybe they should have a protocol for feed access. So even if cameras are there, access to feed will be closely documented and need based.

I grew up without cameras in schools or streets , today you see them sparingly in streets, I feel you need them more in streets, residential buildings, public institutes and roads(traffic violations) as these collect evidences against incidents. What seems irrational to me is not just the prioritisation in implementation of covering schools but What crimes are they preventing in the classroom, is it a teaching aid or a tool for parents to monitor their wards behaviour? Applying technology to filter content is a good thought for damage control but we need to question the purpose it addresses!