Health is amongst the most discussed, debated and fraught over topics in the public discourse. People are increasingly becoming anxious about how to get or stay healthy. This anxiousness provides fertile ground for fitness trends and fads to propagate, even as public health in general continues to deteriorate worldwide. Every few years, new diet fads and trends, backed by “research”, make an appearance and promise weight loss and solution to every single health issue we face. They make heroes and villains out of different food groups, but the one thing that is common to all diet trends is this – stop eating the diverse, traditional foods that you have been eating, and start eating a uniform diet from the food industry. That is the common self-serving narrative being propagated.

Countries like ours, the low to middle income countries (LMIC), go through this phenomenon, namely ‘Nutrition transition’ (Barry Popkins, 1993), wherein we replace our age-old foods and eating practices with a more “western diet”, implying more processed and packaged foods and more consumption of meat. This, coupled with decreasing physical activity and exercise, is now considered to be the leading cause of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like obesity, diabetes, heart health, cancer, mental health issues, etc. NCDs are going to cost the world USD 47 trillion between 2010 – 2030, a report prepared by the World Economic Forum and Harvard School of Public Health in 2011 stated, and the big share of this cost will be borne by the LMIC.

These were some of the considerations that led me to start the 12-week fitness project. It was an initiative to buck this trend – to prove that conversations about health need to move beyond the carbs-protein-fat-calories narrative; that it needs to be looked at from a much broader perspective, a multi-disciplinary approach that links individual health to local economy and global ecology; and that it needs to account for climate, crop cycle, agricultural practices, cooking traditions and food heritage of the region you live in.

The project, that ran through the 1st week Jan 2018 to end of March 2018, was implemented on a weekly basis – one healthy practice was recommended every week, and these were to be followed cumulatively. Instead of making wholesale changes to the current eating patterns and lifestyle, we felt that a gradual approach will work better. The idea was to learn from the mistakes we make in our New Year resolutions every year, which invariably aim high but don’t last long. A cumulative approach was therefore chosen.

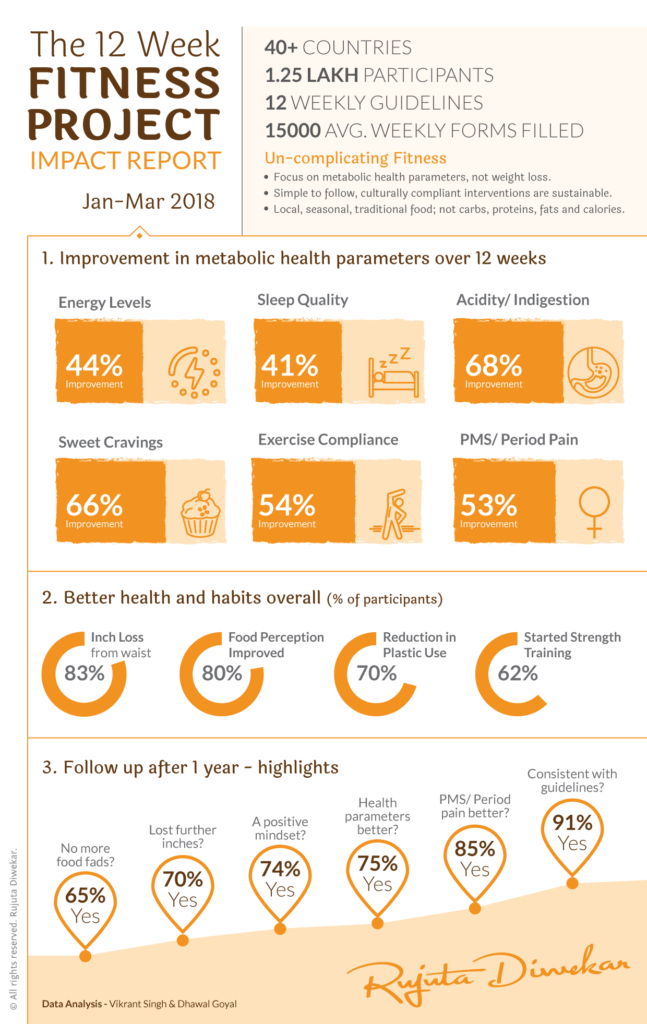

More than 1.25 lakh participants from over 40 countries across the globe registered for the project. At the beginning of the project, the participants self-rated their score on six metabolic health parameters – energy levels during the day, sleep quality in the night, sweet cravings post meals, acidity/bloating/indigestion, exercise compliance and PMS/ period pain for women participants. These parameters were then tracked throughout the 12 weeks. In addition, they also tracked inch-loss from waist at the navel.

The 12 guidelines provided to these participants covered three broad categories – food and eating practices; physical activity and exercise; and lifestyle and habits. The intent was to incorporate native food practices, and build a healthier lifestyle through exercise and other activities. Some of these guidelines included using ghee, native cold-pressed oils and other local, seasonal fruits and vegetables; using cast iron vessels for cooking instead of those containing aluminium; strategy for pacing meals through the day, etc We also suggested physical activities that could be easily incorporated into one’s lifestyle. Minding the body’s posture, sleeping habits, gadget use and use of plastic, etc., were some other aspects that were covered under them.

These guidelines combined the latest in nutrition and exercise science, with the time-tested and culturally relevant practices and beliefs. They appealed to common sense and people could relate to most of the guidelines at an intuitive level. The idea was to broaden the narrative of health beyond food groups and introduce the concept of food systems so that health conversations move beyond counting calories and instead look at a more wholesome and bigger picture.

Incorporating the guidelines led to a significant improvement in metabolic health parameters (40-65% on average) and also led to loss of inches from the waist (more than 80% participants lost at least an inch). The easy and sensible nature of interventions (guidelines) also ensured that even after one full year, most of the participants (more than 90%) continue to inculcate them in their daily lives. This was one of the biggest outcomes from the project. Sustainability is the corner stone of long term good health and harmony and latest scientific research also says that food diversity and traditional diets will go a long way in countering climate change affects.

Participants also reported an improved relationship with food (no more fears and fads). This was the exact opposite of the anxious, fearful, confused state of mind that most people experience when it comes to health. Other positive reports from the participants included a reduction in the usage of plastic in their daily life and a generally positive outlook.

Public health messages therefore should focus on advocating local, culturally compliant and traditional foods and eating practices along with increase in physical activity and exercise and improvement in daily habits like gadget and plastic use.