They searched and searched, searched some more—

it just kept disappearing.

After all that search, when they couldn’t find it,

they gave up and said, “Beyond.”

– Kabir

(Tr. Linda Hess)

While artist Bose Krishnamachari embraces the direction of destiny in his life, he continues to search for a threshold where extremes thrive. The threshold that Krishnamachari dwells at is characterised not by balance but by a transformative simultaneity. Walking on the margins of his theory and practice, he continues striving to achieve this transient site of temporality to allow more creative, ideological, and intellectual osmoses to take place between various disciplines. The surreal, chaotic juxtapositions of contradictions, contrasts, and polarities of his life (un)take shape in his work. In a practise and philosophy as ‘experimental’ as this, there is no space to give up. Everything exists here and now, in the threshold. It is here that Krishnamachari challenges the limits of his own practice, of the closeness between the opposites of ornamental maximalism and abstract minimalism, and of the order in chaos and the chaos in order. The contemporaneity of his world of art and thought does not observe but rather challenges all the rules and possibilities, for they do not exist ‘beyond’.

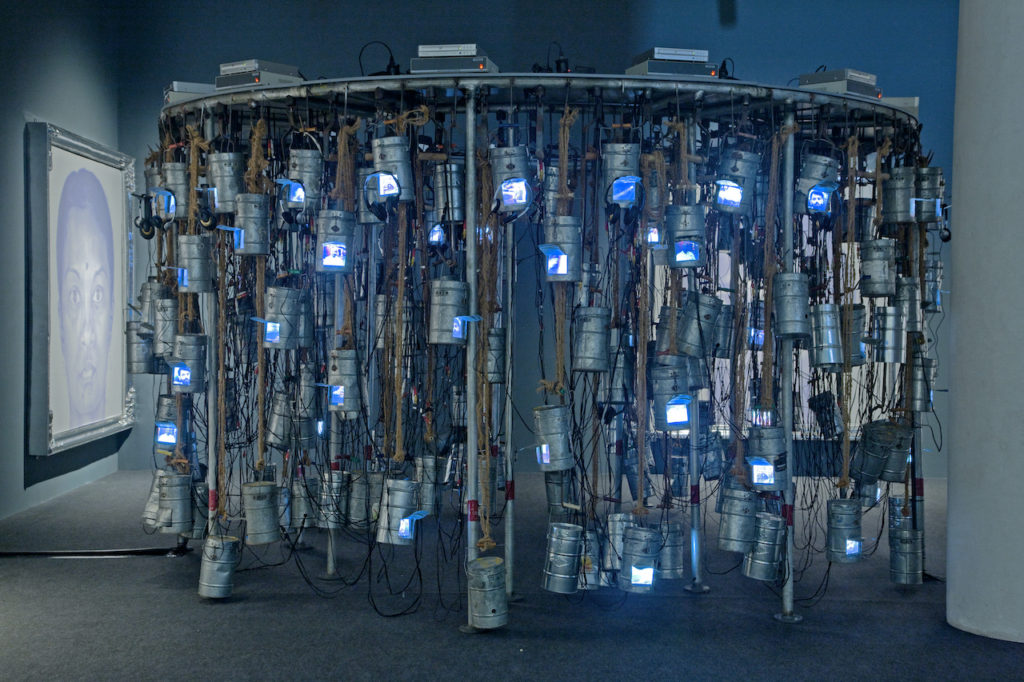

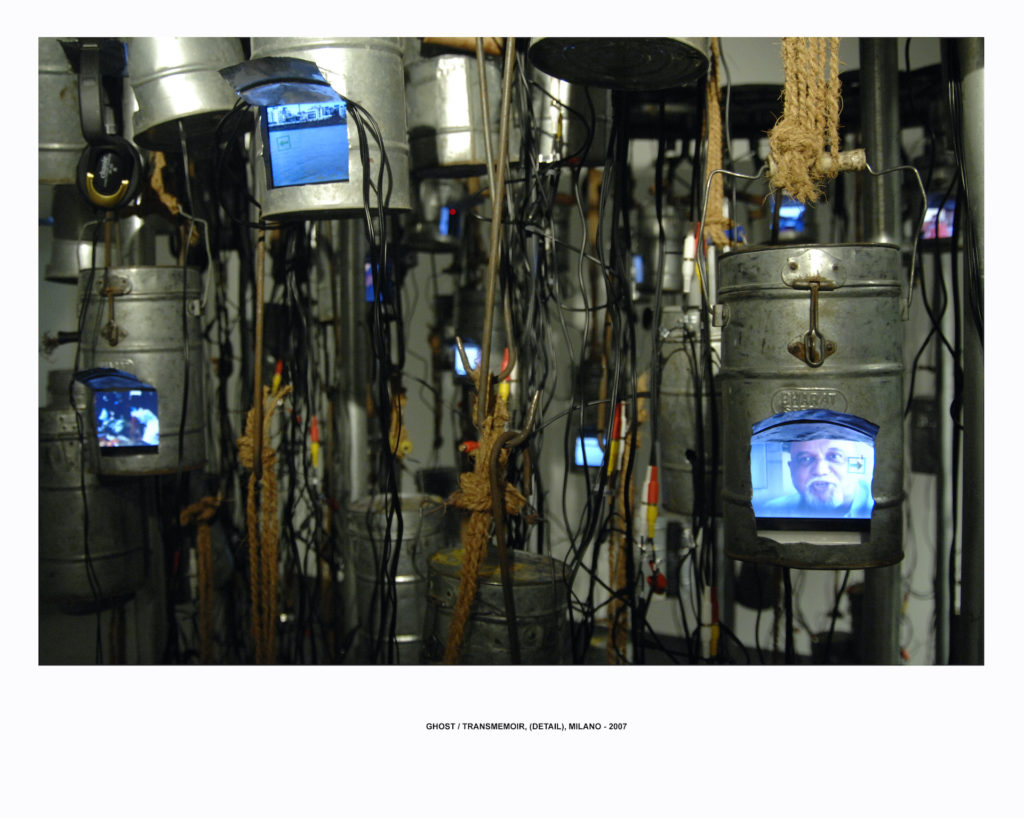

Some years ago, Krishnamachari’s gaze got affixed on the tiffin of the dabbawaalas, a remarkable icon from Mumbai symbolising survival, which has featured in many of his projects since 1994. In an attempt to record the memory of the history of what is, the tiffins, objects of the everyday, became his archives-in-progress. The history of the present exists only in its continuous disappearance, and hence can only be mapped in a transformative manner. Krishnamachari’s engagements with the intangible, the doubtful-in-existence, eventually came alive as ‘Ghost/Transmemoir’—an interactive register of memory and transformation. Unlike the never-ending order of the 108 beads of a rosary, entangled cables and instruments brought together the chaos of the memories of hundreds of people. The day-to-day frames, embedded in the 162 dabbas, were reflected through the recorded testimonies of 108 bellies of Bombay—first in Mumbai and later in New York, Milan, Rome, Singapore, and many other geographies, as these memoirs of Mumbaikars kept translating to and trespassing on stranger cities and hearts.

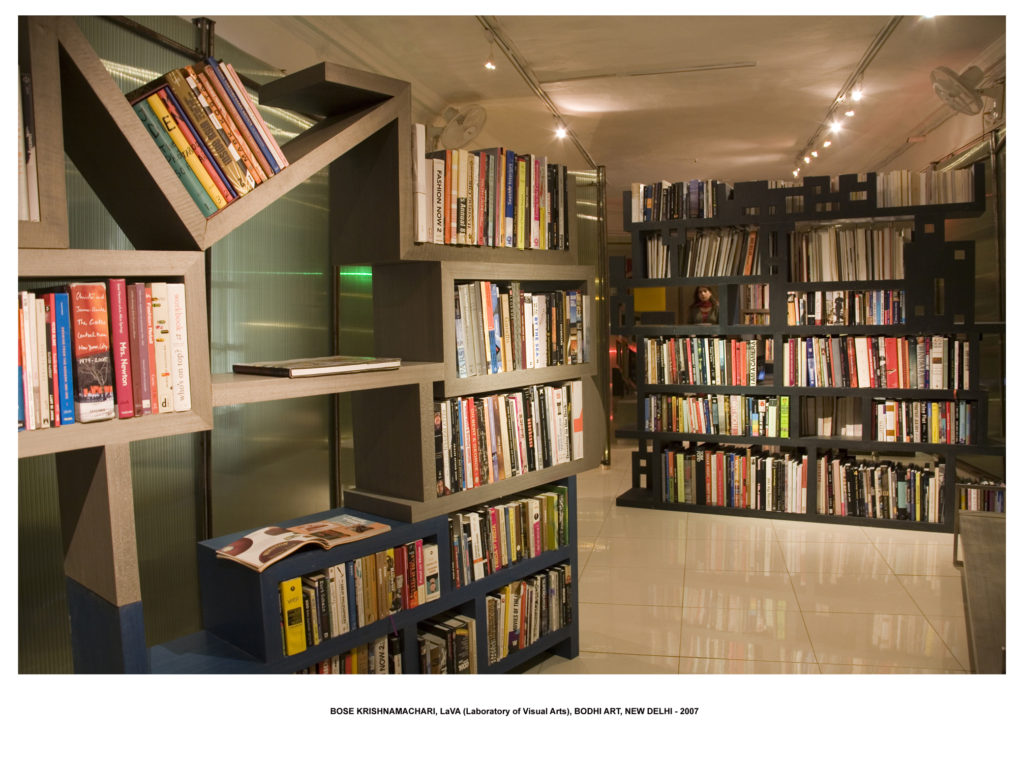

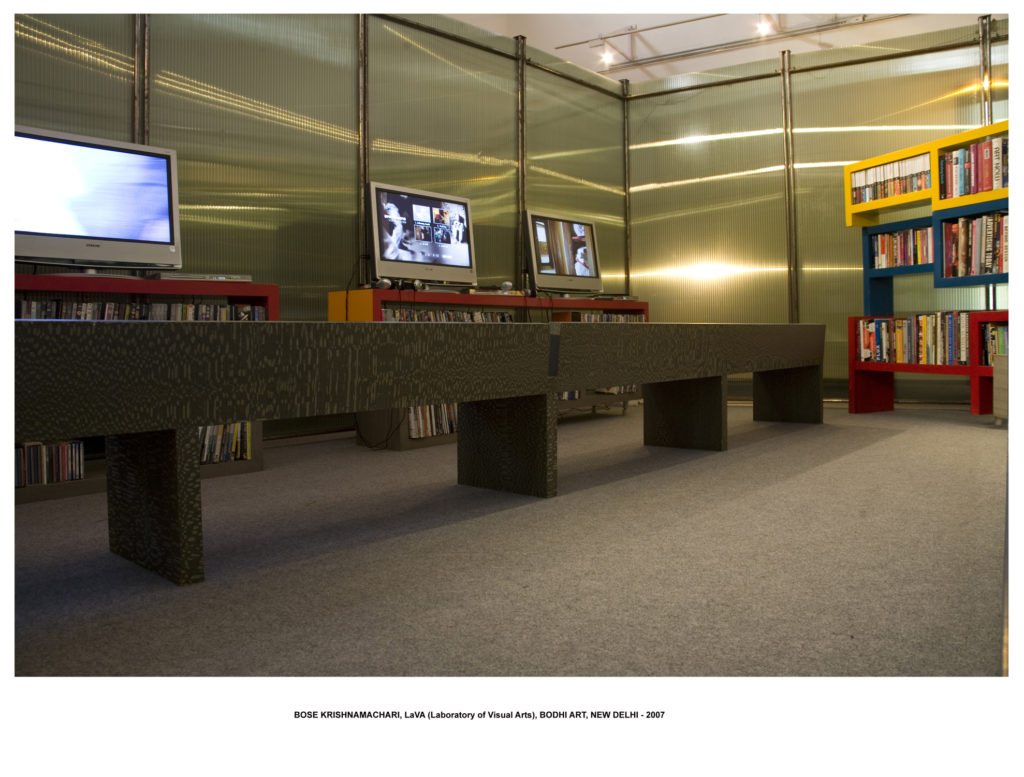

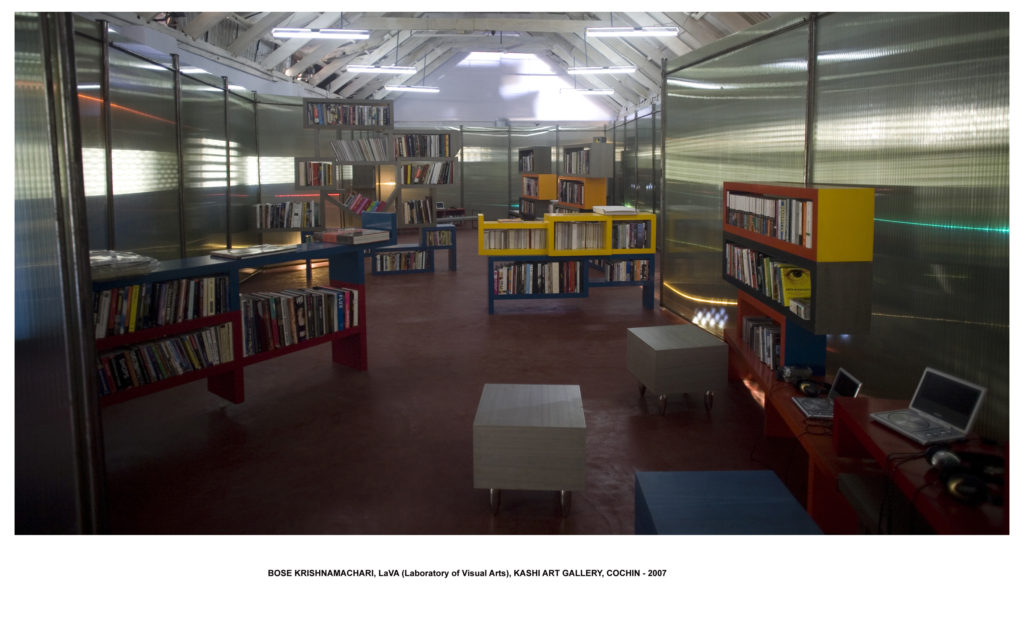

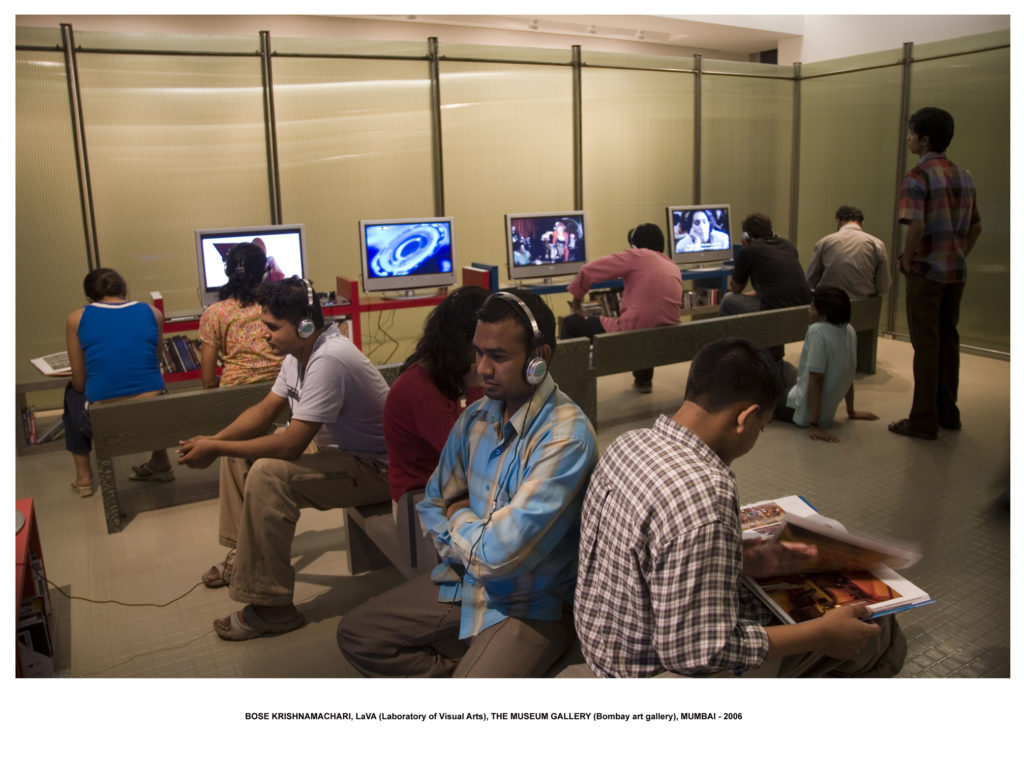

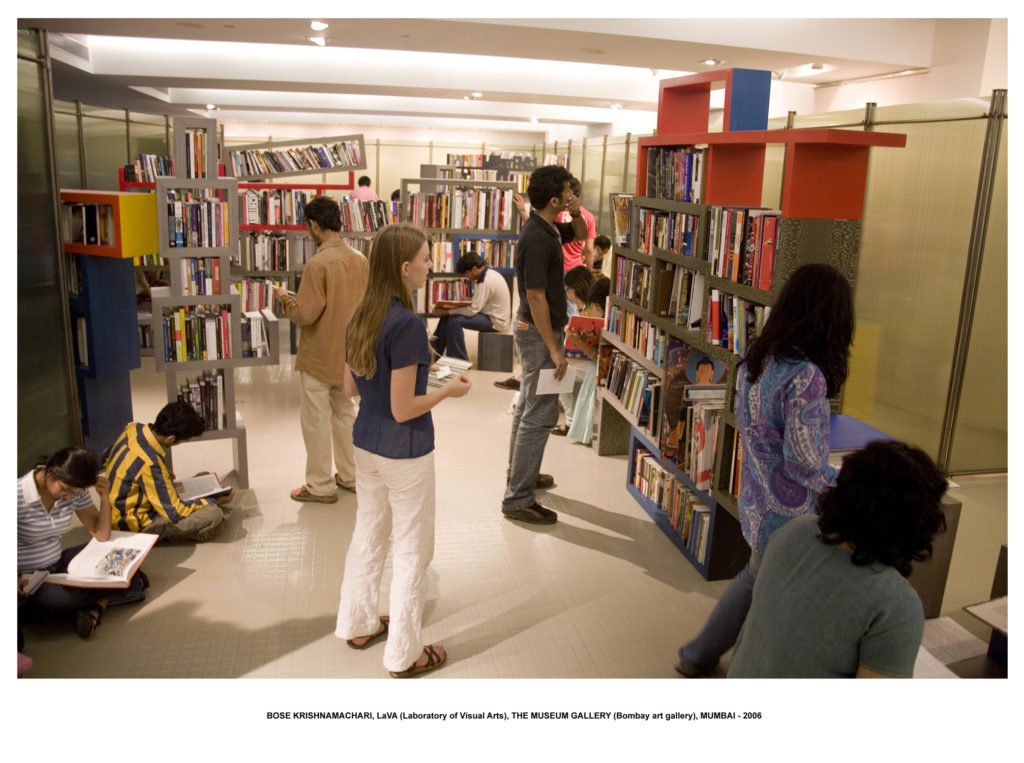

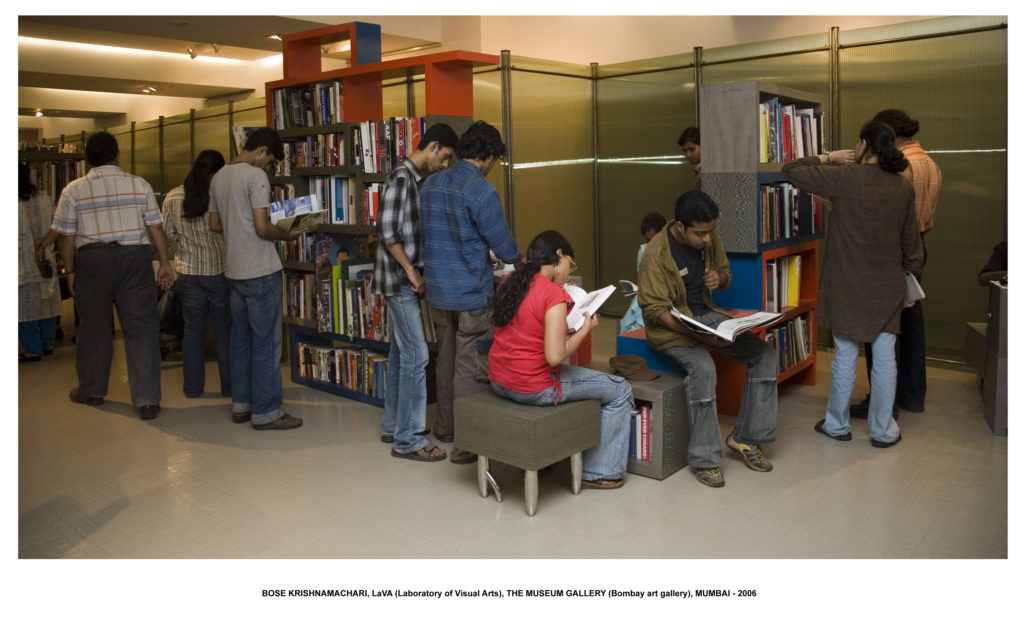

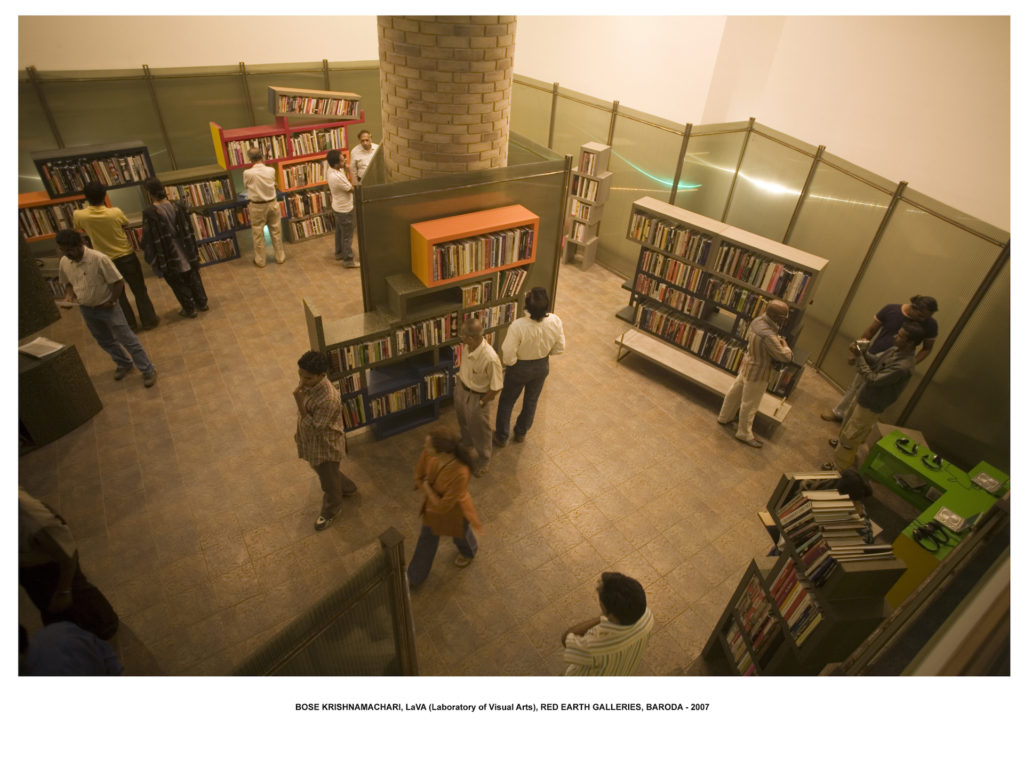

Krishnamachari sees juxtapositions as the contradictions or contrasts between one space itself; it is the conscience of the artist and the potential of the space that ensures that everything can be brought together. It is the artist’s commitment, he believes, towards their individual self and the collective of their immediate world that (re)shapes and (re)organises spaces. While training as an artist, Krishnamachari experienced an uneasiness with the lack of accessible content on art. He would spend hours browsing through the shelves of a small bookshop in Fort Kochi, searching for something or the other. Realising that many like him are always searching but hardly find, he decided to put these remnants of a personal void in motion. Through the conceptual work titled ‘Laboratory of Visual Art’, an effort was made to reach out and cater to the other seekers of art. The hundreds of people who would arrive at Max Mueller Bhawan’s gallery space in Mumbai only to know more were its desired stakeholders. This laboratory, with essentially about a thousand books and DVDs collected from around the world, then travelled to Delhi, Kolkata, Baroda, Bangalore and Kochi, before returning to Mumbai and to Krishnamachari’s memories.

laVA an instalation by Bose Krishanamachari baroda 1st feb 2007 photo-Ravi Shekhar

Conceptual works are the real investment of the artist that Krishnamachari is. They expose and externalise the artist’s intimate thoughts, laying them bare in an invitation to the people who they are conceptualised for. They do not belong to the artist, the gallery, or the market, but only to the public, to intervene in its existing discourse. All individuals, including the artist, are always obsessed with something or the other. These obsessions welcome us to step into them; the escape is not always guaranteed. They reflect to us our sense of the self, like a mirror—entrapped. Krishnamachari, who strongly rejects the assumed dichotomy between one’s artistic sensibilities and one’s life, investigates such obsessions, which we tend to merge into. His latest work with images, icons, and numbers inscribed on the faces of mirrors looks into the eye of the obsessed, overwhelmed viewer. “The Mirror Stage reveals the I,” Lacan theorised at the Fourteenth International Psychoanalytical Congress in 1936. “The Mirror Sees Best in the Dark,” Krishnamachari announced at Emami Gallery in 2019. “Do we ever step into the same mirror twice?” we ask at LILA in 2020.