Shiv D Sharma: Before we get into discussing your fabulous work, I would like to ask what got you interested in queer studies and what do you think is exciting about queer studies now, especially given the theme of this edition: evolution?

Kareem Khubchandani: I understand queer studies as a field that attends to the many ways in which gender and sexual normativity is institutionalised, as well as how gender and sexual dissidents make pleasure, culture, and community under limitation and duress. I came to queer studies only in graduate school, in search of frameworks to understand how and why gender and sexuality matter to migrant life, and to learn what kinds of worlds queer migrants build for and with each other. I’m excited about the growing interdisciplinarity of queer studies, that includes literary, historical, and cultural analyses, as well as political theory, religion, legal and urban studies. I love that queer studies now skews toward queer of colour criticism, Black studies, and trans studies, as manifest in the works of authors such as Hortense Spillers, Sara Ahmed, José Esteban Muñoz, Cathy Cohen, E. Patrick Johnson, Gayatri Gopinath, Dean Spade, and Susan Stryker, who appear regularly as key theorists in scholarly writing.

I’ll say also, I love when queer studies thinks with and through sex and desire: Juana Maria Rodriguez, Tan Hoang Nguyen, Mireille Miller Young, Ariane Cruz. I hope queer studies continues to remain promiscuous! I think it has taken a very long time for scholarship emerging from locations and contexts beyond the US and beyond the western hemisphere to be taken up widely. But that seems to be changing, and we are now able to think through questions of gender, sexuality, queerness and desire from perspectives other than the Euro/American-centric ones. What’s exciting is that K’eguro Macharia’s book Frottage (K’eguro is an independent scholar writing from Kenya) won GL/Q’s Alan Bray Memorial Prize recently, and all the winners of the 2019 CLAGS awards work outside of the US. Maybe things are shifting?

SD: Just to bring it outside the academic context a little bit, what would you say queer studies (or the queer perspective) brings to our social, cultural and political lives, especially in the way it allows us to understand our bodies today?

KK: Gosh, ok, this is a big question. I love queer studies because it has given me the tools to think about those things that I enjoy but have long felt ashamed about: gender non-conformity, same-gender desire, casual sex, purposeless dance till the wee hours of the morning, sequins. We know that gender and sexual non-conformity is/can be life threatening, and many of us perpetually live with such a fear. But queer studies reminds us that the shame, embarrassment, fear, marginality that we might feel are actually systemic, and it offers history and context to the stakes of practicing gender and sexuality. It shows us that an assemblage of laws, institutions, authority figures are always set in place to regulate gender and sexuality and to punish us for not conforming. At the same time, there is an ethic of repair in this project: it helps us attend to the wounds of gender and sexual dissidence, of desiring the wrong kind of body, of embodying gender ‘improperly.’ It’s a field that invests in the possibilities of pleasure, fun, and play, and which takes seriously that these are ways of repairing and even undoing the damage caused to our psyches, communities, and histories by the ubiquitous violence of patriarchal heteronormativity.

I’ll also add that it is so easy for gender and sexuality to not be taken seriously as nodes through which power works, as points of application of power mechanisms, and as central to the way we make decisions about life on a daily basis. This is perhaps because gender and sexuality provide the most quotidian forms of the exercise of power – heternormativity and gender conformity are so taken for granted; so routinised and normalised. I think the ‘queer’ disrupts what we think we ‘naturally’ know as gender, sex, body, desire. It takes little for granted and rather asks us to pay attention to where we get our ideas of what is normal, and what the stakes are of disrupting those norms.

SD: Many of us know you as LaWhore Vagistan, before we encounter your work as a professor at Tufts and as the author of Ishtyle. In the preface to your book, you mention that you move between both the academic and the queer nightlife spaces as a drag queen. And that drag is a research method in your work. Could you explain what that means for you and how that might allow us to look at both academic work as well as arts/performance differently?

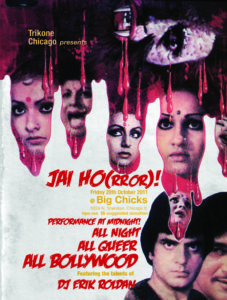

KK: I fell into drag when I got to graduate school. I have long loved drag, but I never had a dream or desire to do it myself. To be quite frank, at that time, my performance of masculinity was already tenuous, and if I wanted queer men to like me, drag felt like a dangerous choice. I did drag at a queer Bollywood club night in 2009 as part of a fundraiser, and LaWhore has stuck around since. And eventually, it found its way into my scholarly work. The nightclub became a joyful field of ethnographic research, and a place to seek answers to some of the questions that I had been thinking about in relation to gender and sexuality. Being in drag meant being up on the stage while the rest of the crowd is down below. From that vantage point, the nightclub can really transform; the cliques and clumps come into relief. The quality of our data changes when we take into consideration from where we look, what performance studies scholars call ‘proprioception’. From there, I could see all the other performances happening: sloppy making out while people ignored my show, people lip-synching the song back to me better, others replicating the exact film choreography, and some finding elaborate theatrical ways to tip me. I was able to see all that ‘drag’ happening on the dance floor, and it taught me how to look for artistry out in the crowd, and not just up on the stage. So strangely, doing drag in the club has taught me to look away from the stage as the exciting space for performance and politics in the club, and towards more mundane aspects of nightlife and to look at my audience as performers.

SD: That’s fascinating – that your drag involves both the labour as an artist and the labour as a researcher. What I also hear in your response is a certain kind of mutuality or co-facilitation that drag as a research method depends on. Do you think this prompts us to understand the nature of knowledge production differently?

KK: I’ll answer this with a bit of an anecdote. One of the things that emerged in my research is the obsession of queer people with film divas, and for the eighties-born friends who appeared in my interviews, it was particularly Sridevi and Madhuri Dixit. ‘Diva worship’ was not something I knew about before doing this research, before queer studies, before doing drag. As I learned of the value of Madhuri and Sridevi – whom I was of course familiar with but did not have that nostalgic attachment to – I performed their hits in drag. And when I did that, I got even more research data. People had such visceral responses to those performances, and they would come up to me to tell me what they thought and felt: “The last time I heard that song was on my grandmother’s lap,” “That’s my song,” “That was a garba favourite!” So, as my research and scholarship informed my performances, my performances then elicited more research. In this way, drag taught me important lessons about how the researcher elicits data in the field; that I’m never documenting things the way they just are, that data is produced in dialogue. So yes, it does ask us to consider knowledge production differently, as co-constituted. In chapter three of my book, I offer extensive quotations from my interviewees as a way of showing how they theorise, but I also name how they name me, how they remember something I did, somewhere we were – their memories of our relationship shape what they tell me. Beyond the book, I delve into this dialogic method more deeply in an essay called Dance Floor Divas.

SD: What kind of political work is performed by drag, both in the contexts of nationalist politics and in relation to contemporary queer feminisms?

KK: I think drag is an accessible art form in that it only requires a body. Sure, there are versions of drag that are more elaborate – with dress, makeup, heels, binders, etc. But the dancing body alone can re-craft and invent genders; what Naomi Bragin calls “corporeal drag.” Further, if gender is the repertoire of drag, we are at no shortage of exposure to the form. I think then, drag’s politics lie in its proximity to things we know so well.

Drag’s politics find their roots in the cross-dressing queens and trans women who referred to themselves as drag queens (for lack of a better term, and also because it was the right term) and fought against the police in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district and NYC’s West Village. Drag’s politics is rooted also in the quotidian affirmation of gender that it gives to people who practice it; sometimes that affirmation happens when they take the drag off, and sometimes it’s when they put it on. For me, drag does its work in those moments when I look in the mirror in full face and feel fierce, and also when I take the makeup off and return to some restful state of being a little bit boring. It’s no surprise that I’ve seen Harriet Tubman drag three different times. All of these performances have had me in giggle-fits; drag’s politics also lie in its capacity to de-throne the violent histories and imagery and instead produce a collective feeling of euphoria in the here and now. What I’ll also say, is that drag is never just working through gender; its incitements are always working through multiple referents, and gender subversion isn’t the only thing that makes drag ‘work’. Drag exercises its politics when performers do numbers that critique enslavement, carcerality, and settler colonialism. I’m, in fact, working on a short book titled Decolonize Drag for O/R Books that catalogues a range of drag artists who use the form to stage critiques of imperialism.

SD: Queer nightlife spaces can be buoyant spaces for all kinds of queer world-makings, but they are also spaces where one may experience shame and abjection. And you do attend to the exclusions in these spaces along the lines of class, caste and race. What you write also makes me go back to Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner’s famous essay “Sex in Public.” How do we ‘fix’ this? What kind of spaces do we need to change this situation?

KK: I love that essay! I also realise that not a lot of people want to be in that nightclub where Berlant and Warner witness erotic vomiting. I’m not sure they wanted to be there either. But what they say is that certain kinds of public intimacies (like intergenerational erotic vomiting) were being made impossible by state governance using morality to produce neoliberal privatisation. There are a couple of things to say here. As spaces open their doors and become ‘inclusive’, they might also become more susceptible to co-optation. In Ishtyle, I give the example of Toronto’s Besharam that takes so many measures to try and keep all parties present (gay men, trans women, straight cis women, straight cis men) happy. But regardless of all the work they do, frictions will still happen, so will really gorgeous intimacies that can’t be accounted for in advance. My suggestion is a thoughtful curatorial eye toward making nightlife spaces inclusive, along with a loose hand that gives people freedom to make worlds on the terms they know best. What I’ve seen work at parties like Papi Juice and Chances Dances is a pre-advertised code of conduct, or even one printed and posted in the restroom, that names the priorities of the space: “In this space we believe…” or “We centre people who…” etc. It signals to folks who don’t have similar social, political, ethical commitments that this space isn’t theirs, and they don’t show up!

SD: What is so refreshing about your work is your attention and attachment to the aesthetic, to pleasure, to desires. Can you say a little bit about the relationship between the aesthetic and the political, and the role that arts can play in social change and transformation?

KK: I had this moment early on in grad school reading Jill Dolan, where she discusses realism as an aesthetic, and this felt like smack in the face. Of course. Duh. I always felt like a bad intellectual for not liking these European films/art films made in a realist mode. I was working on the assumption that these movies are supposedly good because they are real, normal, true, etc. But there is no neutral form or style, and once you see it, you can’t unsee! Hegemony is not just a matter of morals or systems, but in fact, aesthetic and style have a great role to play.

And there are certainly dominant aesthetics at play in the nightclub, the ‘blown out’ hairstyle you’re supposed to have, the futuristic chrome interiors of the bar, the privileging of electronic dance music. These all participate in reproducing the cosmopolitan world that nightlife is supposed to be. And you can feel it when the proper or dominant aesthetics have been disrupted. DJ Dynamite in New York will play songs like “Jiya Jale” and “Roop Suhana Lagta Hai” at a party, and you realise that these sounds, lyrics, beats and moods do not belong. But this doesn’t mean that they aren’t fun, or great, and in fact the pleasure doubles not only because they’re fun songs, but because they’re in the wrong place. There was a night at a gay party in Hyderabad where the DJ played “Deewani Mastani” three times in less than an hour, and really it was so wrong but just so good because I’d never imagined dancing to this at a bar on repeat.

Thinking through aesthetics forces us to recognise how what is termed as “natural”/“normal” is always deep down (or sometimes even in a glaringly obvious manner) the matter of a formal choice, an aesthetic judgement, and that its dominant meanings are only secured through repetition. Suddenly the most mundane things we know – whether it is the side-to-side shuffle when we dance, good or bad smells and tastes, or the architecture of our home – come to have a political history and a possibility. Such a deconstruction of the world as we know it, I think, gives us a permission to play, to be playful, as a radical act of subversion.

SD: You know… one thing that your work does is of course to foreground politics within the party. But what’s most wonderful, to me, is that you also bring the party to politics/learning. I love the idea of ‘play’! What would you say is the relation between play/playfulness and critique? Shall we go back to the idea of promiscuity (as a heuristic? as an ethic?), as you mentioned in response to the first question, if you’d like to say something more?

KK: Just going back to my answer above, what I said about not liking the realist film… I do like masala Bollywood, and I like memes and TikTok, and I like things that people think of as frivolous, like nightlife. I like those sillier, playful, errant objects. They bring me a lot of relief and release. They also have the potential to be shitty and terrifying. But like I’ve said, these are all things I am attached to… and to simply eviscerate them for all the ways in which they reproduce state and social violence destroys them for me too. There’s a version of a critical studies scholar who studies institutional violence but has that ‘guilty pleasure’ on the side that they indulge in; that object they give themselves permission to indulge in (e.g., Ekta Kapoor serials, branded fashion, Zumba). I study the things I love, and look for the small gestures of joy, pleasure, intimacy, creativity, strangeness that erupt in the party… alongside, as you say, foregrounding politics. I’m not saying that my version of balancing criticism and pleasure is better than that scholar who has that untouchable guilty pleasure that sits aside from research, but my approach has been a way of sustaining pleasure in my life and gifting it to others too. I don’t want people to read my work and say “Ugh, nightlife, so violent,” or “Drag? So commercial!” Nightlife and drag have saved lives, have been essential to political formation, but here I go falling into the trap of trying to say that these things matter only because of politics. They are also fun, complicated, weird places of invention that really made me feel magical and beautiful at various points in my life and I don’t want to foreclose those opportunities to others. I’ll say also, I don’t think that this approach compromises critique, it just weights it differently in writing. Critique isn’t the conclusion; rather, it is the imperative to look for pleasure and play inside the party.

SD: Finally, I want you to say something about your love of the aunties and your latest work on “auntology.” Why ‘aunties’ and if I may put it that way, what do ‘aunties’ have to teach the world?

KK: I think this is where queer studies and its playful imperatives have really taken over my life and thinking, and now everything is queer until proven otherwise… including aunties. There are long answers to this, but to be brief, I’ll say: 1) while aunties have absolutely disciplined my gender, weight, skin colour, queerness, etc., they have also fed me, taken care of me amidst family crises, and been a source of aesthetic inspiration for my drag. Queer studies’ reparative mode (see Eve Sedgwick, amongst many) has trained me not to dismiss those not-so-queer things as not-queer at all. 2) getting older, uncle doesn’t feel like a gender I want to grow into and so aunty is what works for me. 3) on TikTok and IG [Instagram], aunties are the object of Gen-Z’s ire (in ways that the mother is not!), and so she’s an important pivot around which gender’s futures are being imagined.

I think that the aunty figure becomes such an important cypher for thinking memory, migration, gender, fashion, pleasure, discipline, aging, family, and the limits of the home space. She is such a ubiquitous figure in public cultures and yet severely undertheorized… so I think we have lots to learn by thinking with her. As I develop my next monograph, “Auntologies: Queer Aesthetics and South Asian Aunties,” I don’t want to be alone in this research… so I curated www.criticalauntystudies.com as a way of putting aunty scholarship in conversation across diasporas to see what happens.

Donation to LILA is eligible for tax exemption u/s 80 G (5) (VI) of the Income Tax Act 1961 vide order no. NQ CIT (E) 6139 DEL-LE25902-16032015 dated 16/03/2015