Almost thirty years ago, on July 30, 1990, Ahir Narayanbhai Meramanbhai Karangia took his energy off peacocks for a moment.

He didn’t drift too far though, focusing instead on the less fancied floricans, an endangered species of the bustard family of birds. Karangia wrote a letter to the Secretary of the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) after reading a pamphlet they published titled, ‘The Vanishing Floricans’. He’d received it from his local forest officer. At the time, Narayan Karangia was a young farmer in Kenedi village in Jamnagar district in Gujarat. He also ran a centre to protect peacocks and other birds, something he has gained so much reputation for in the years since that he is called the ‘peacock doctor’.

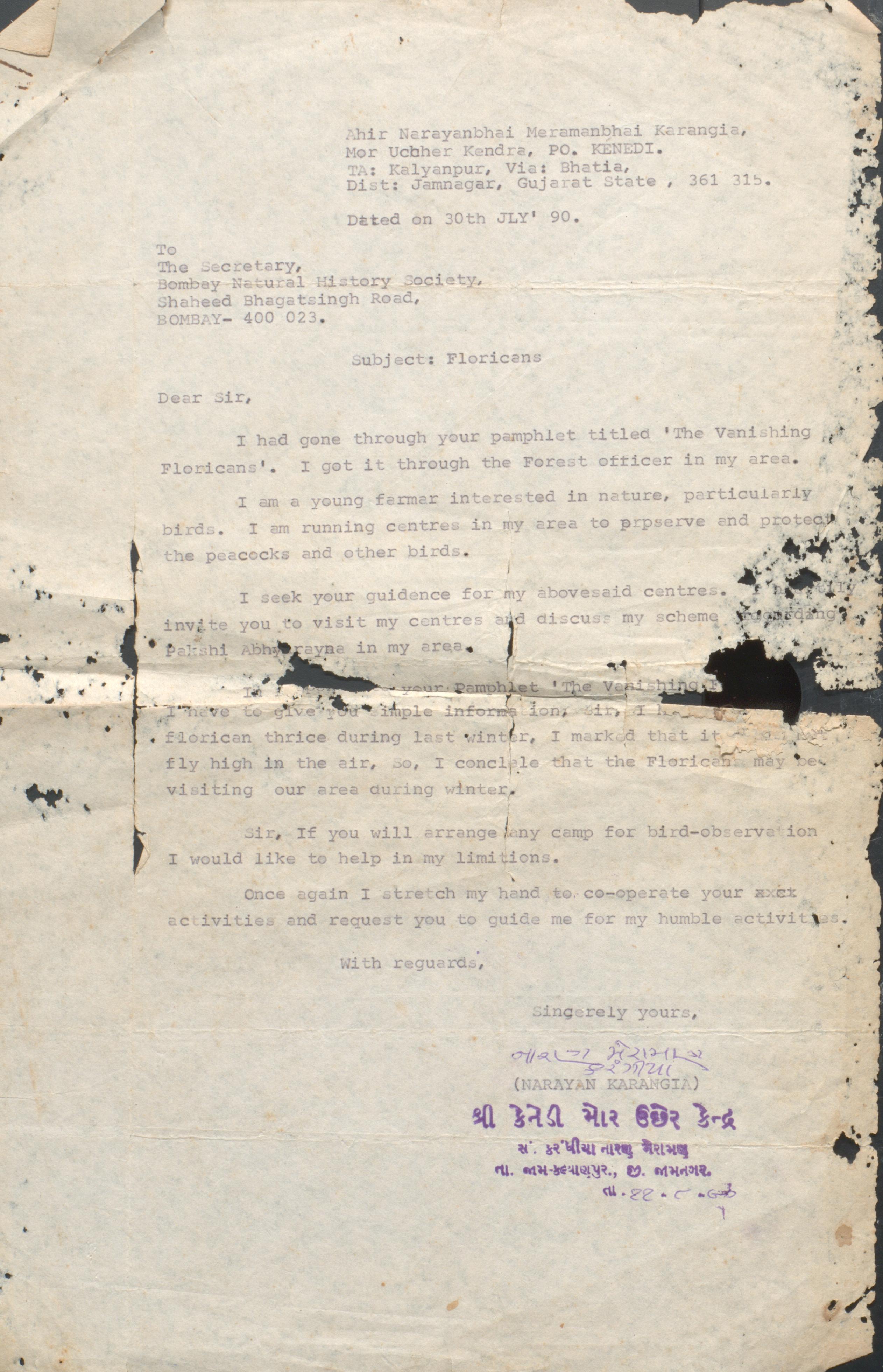

But that day, Karangia was interested in floricans. He had seen the bird thrice during the previous winter, noting that it could “fly high in the air”. It must be visiting his area. His letter is typed in English and signed and stamped in what looks like Gujarati. “I stretch my hand to co-operate [sic] your activities,” he told BNHS. “And request you to guide me.”

Karangia’s letter is in a folder with a unique identity number today – MS-004-1-3-3-7 – tucked inside an acid-free box at the Archives at NCBS. The letter is part of the Ravi Sankaran Papers at this archive, a public space for the history of contemporary biology in India. Sankaran was an ornithologist who, in the 1980s and early 1990s, studied the floricans and the Great Indian Bustard while at the BNHS.

Let’s rewind and assess what just happened. A thought emerged in the fields near Kenedi village after observing a few floricans. It got typed up on a letter that moved from post office to post office to finally land at the BNHS. It eventually reached Sankaran, likely moving along with him from city to city – Bombay, Coimbatore, Madras. Sankaran, for reasons only known to him, kept the letter. The archives appraised the letter as being pertinent to the context and process of his work. And thus, from a wild expanse, a public space, the letter now sits in the private confines of a box. Ironically, it is more public than ever before.

Public comes from Latin, publicus – something that is both poplicus (of the people) and puber (adult). And what seems like the opposite, private, doesn’t seem so far out when we consider its origins in privus, Latin for individual. The people cannot exist without the collection of individual thoughts and actions. A public cannot exist without the private.

What eventually becomes an archive starts from imagination. In her essay, The Site of Memory, Toni Morrison lingers on this thing called imagination. “…The act of imagination is bound with memory,” she writes. This is true for the archival object as well, which relies on the imagination of the archive to make it thrive in public and connect diverse worlds of memory. For instance, when I first saw the letter and saw Jamnagar, I was instead transported to fourth grade, a time when I would keep re-reading Ruskin Bond’s ‘The Adventures of Rusty’. Rusty was a young kid who yearned to escape his school and join his uncle on a ship. He just needed to find a way to get to Jamnagar and then he would be on his way to see the rest of the world. “…The ship would call at Jamnagar towards the end of the month, I felt a deep thrill of anticipation. Here was my chance at last!” dreamed Rusty. “Yokohama, Valparaiso, San Diego, London!” Karangia, the farmer, peacock doctor and now florican watcher, had managed to move my imagination back a few decades through his imagination of the flight of a bird.

Today, Jamnagar and those other cities probably look a lot different compared to even a month ago, leave alone Rusty’s imagination. On March 23 this year, the New York Times published a photo essay titled, ‘The Great Empty’ with pictures of normally bustling public spaces in Paris, Sao Paulo, Milan and New York, each devoid of people. “Emptiness proliferates like the virus,” they wrote.

Empty is not the word one associates with public. It’s not in its etymology, and it’s not in its history. Only recently have our imaginations of spaces like Tahrir Square and Shaheen Bagh been transformed, inspired by the reclamation of what belongs to the people. And yet, here we are, swiping photo after photo of that lone cyclist, the jogger, the van laden with goods, crossing what should be a bustling corner in <insert city>.

Do things really fall apart? Does the centre really not seem to hold? For so many, undone by unplanned trade-offs of public policies, Yeats’ The Second Coming will trickle in, and then gush forth into their private lives. For those of us privileged enough to be able to read, to have a home to stay in, with the ability to access and afford essential services, it offers a sombre moment to reflect on the thin lines between the private and the public.

Archives enable diverse stories is what we keep saying at the Archives at NCBS: every person has many stories, and every story has many people. Social distancing, a misnomer of sorts, can also be a moment to rethink our relation to the public and galvanise a coming together of imagination.

The question keeps rising up during and after every crisis: what is the role of the archives and the archivist? Is there a social, even public, responsibility? There is at least one, of course – to try and create spaces to gather representations of the present. There are various current and past instances of these attempts to assess a crisis, whether it is aggregating thoughts on a website, as is being done by the students at St Edwards University in the United States, or providing the tools to create such websites. The Society of American Archivists even has a resource kit for “Documenting in Times of Crisis.”

Turn the lens the other way, toward the work of historians and other users of archives, and we find avenues to contextualise the present by taking a deeper look at the past. Tarangini Sriraman’s analysis of the Epidemic Act and the mirroring of circumstances across centuries is a case in point.

And on his blog, Dominik Hünniger, a research fellow at the University of Hamburg, summarises a range of posts by historians on social media to lend some perspective about the current pandemic. If done right, social media offers a forum for a gathering of thoughts from a variety of people and also the ability for cogent questions and responses to spread very rapidly between them. A tweet and article on “Plague in the age of Twitter” or even the current trend on hashtags like #histmed to understand social distancing shows, in a very small way, that the idea of a public house, the pub, may not be bound by walls.

But perhaps the most important player in an archive is the individual creator of a record, the farmer watching the flight of a bird. The strength of an archive relies in our collective ability to imagine, record and curate. This could be a recording with an elderly family member at home, a set of annotated clippings from the daily newspaper, a journal of activities every day, a photograph of the same frame every day, a reflection of conversations with those less fortunate, a stack of WhatsApp dissents against a State’s actions on its citizens. Each of these solitary acts, each potentially going on in various homes across the world, could feed into an archive at some point. Time, too, adds layers of significance on the objects we curate.

Of course, not every curated object from the present will be catapulted into the public archive of the future. Not every fragment of our imagination will enter an ‘Archive’ the way Karangia’s letter did. Luck, circumstance, decisions and process will do their dance. Eventually, some things will stick. They will remain in the trunk, whether in the shape of a metal chest or a USB stick or a memory spoken and shared. That is the emergence of an archive, the slow coming of age from the private to the public.