In the summer of 2008, Sreejata Roy, one half of the artist-designer duo Revue, visited Khirki and the adjacent village of Hauz Rani. She was working on a project at Khoj, an art residency separated by a few miles from this urban village, for which she was looking for embroidery workshops. Khirki was a hub of artisans, migrant labourers, and daily-wage workers who had migrated from the Eastern lands of Bihar, West Bengal, and Orissa. Some of them had found livelihoods in the local factories, construction sites, and embroidery workshops while others had started their own businesses. Their everyday lives unfolded within the territories of their makeshift stalls that lined the streets, roughly demarcating the private within the public. Khirki was always reverberating with a harmonious motion. In the evenings, knots of people would stand around corners chatting in tongues familiar to them. The loud cries of the local vendors selling everything from groceries to mobile phone cards and renting out DVDs would echo till late at night. Khirki and its people were under the spell of a continuous movement through space and time. However, the migrant-worker communities that dwelled in this neighbourhood often faced exploitation under various powerful modes of hybridity and alienation. While the city deconstructed their prejudices and offered them new possibilities of personal freedom, it also took away and diluted their identities and stories.

Following the interactions and conversations with these communities, Revue launched a six-week residency at Khoj to further these dialogues where the workers embroidered designs on handkerchiefs and perhaps the stories of suffering, loss, and alienation along with them. An artist conveys her imagination through art. An embroiderer shares his narratives through embroidery. Later, visitors were invited to pick up these handkerchiefs—and the stories embroidered on them—in exchange of any of their belongings—their stories.

A New Exciting Space

A New Exciting Space was Opening Soon and the slow-paced life at Khirki was accelerating with a jolt. When the factory-sealing drives in Delhi picked up speed, the migrant workers had to migrate again, their ill-fates branching from Delhi back to their remote villages. The factories were shutting down and moving out, while new and fancier buildings were taking over the space that they once had claimed. A new melody was replacing the old chaotic notes of the public life at Khirki. Standing opposite to the village, the Select Citywalk mall was almost ready to temptingly welcome a sea of consumers with capital in hand. Nearby, the Max Super Speciality Hospital had also started to function. With this blow of spatial and economic change, a new demography started to multiply in the irregular streets of Khirki and Hauz Rani. Housekeeping staff from the mall and nurses assisting at the hospital found solace in small rooms in this urban village. In the years that followed, people fleeing war and instability at home in countries of Iraq, Afghanistan, Congo, Nepal, Somalia, etc. domesticated the old remnants of Khirki. Very soon, the rents escalated and Khirki came alive in the colours of a new public. The dhabas got replaced by restaurants and newer shops took over the memories of roadside stalls. New networks were being formed in the neighbourhood of Khirki. Even the dissatisfied locals, after having resisted initially, came to terms with the social, cultural, and economic change. Khirki, once a village, now became a cosmopolitan hub.

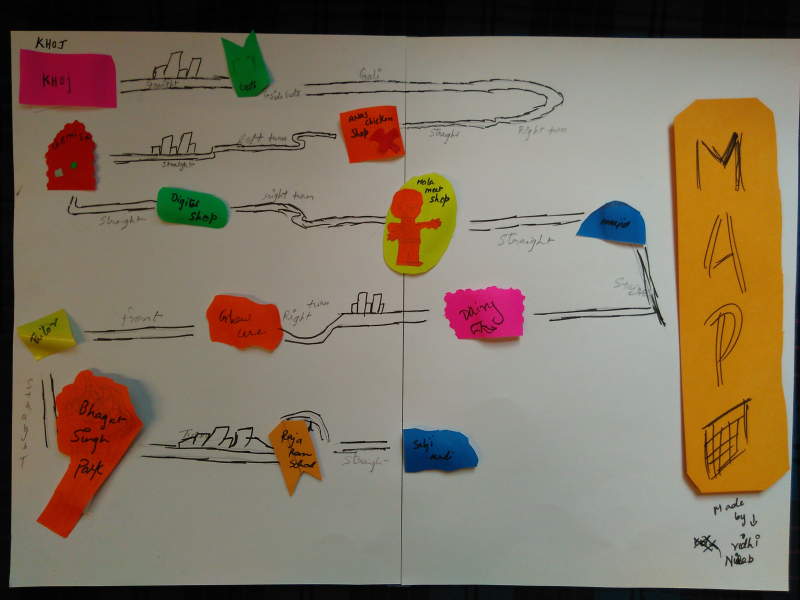

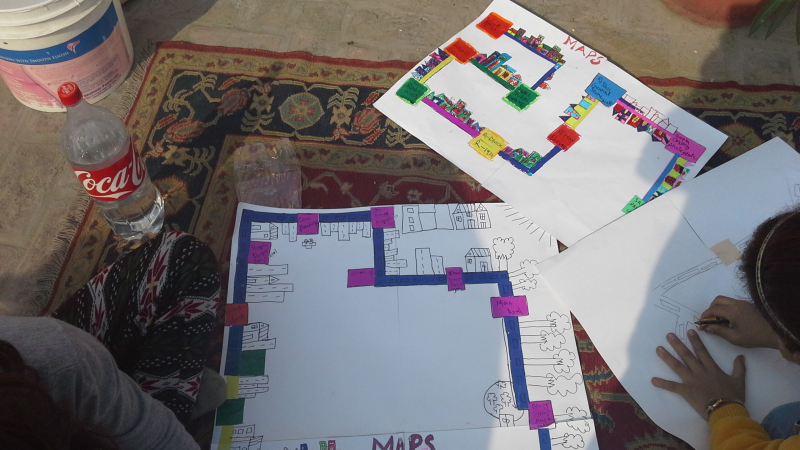

In the new space, while many things changed, some things remained as they were. Only the men claimed the public life. Women, however, could not cross the boundaries of their household. The only time a woman was spotted was when she had to come and buy a kitchen-essential from a shop and rush back. Men, on the other hand, loitered around in the streets round the clock, enjoying teas and fast-food and engaging in social transactions. For the women, the experience of their local public space was gendered. A tea-stall would never feature on their maps. They would never be seen engrossed in a chitter-chatter over a cup of tea or in the market. This became apparent when Revue initiated conversations with the women of Khirki and other surrounding localities, all aged between 18-30, around these issues through Networks and Neighbourhood 1. Looking at the skewed navigation and negotiation of public spaces, Revue asked participants from the area to draw maps on the walls of the Khoj studio. The map that emerged was not to scale at all, but instead reflective of how they viewed social spaces. On the maps drawn by young adults, parks, hotels, and the homes of their friends found a space. While on those drawn by elder women, local boutiques and grocery shops—around which their mobility was limited—got mapped. Even the perception of distance varied from one demographic to another. What was closer appeared far to some and what was far appeared closer to others.

Networks and Neighbourhoods 1

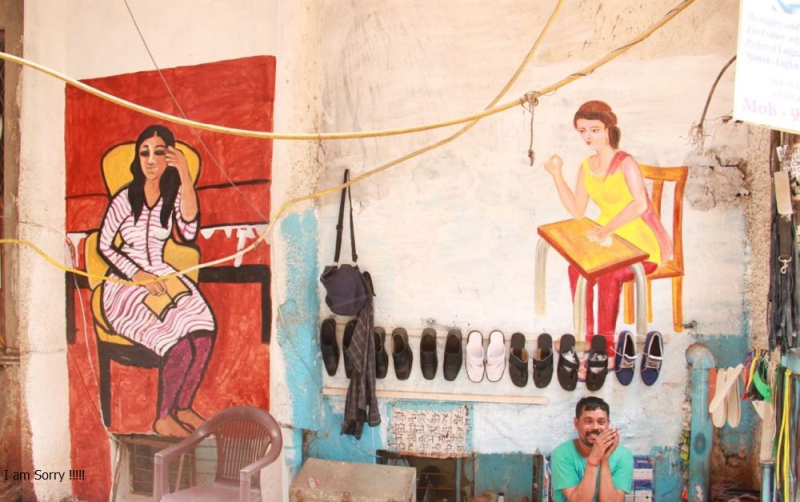

Teenagers and young women from Khirki and Hauz Rani, who imagined and desired a different space for themselves, came forward to visualise it. Within a few days, women appeared in the public space- not in person, but as paintings. An all-female group was sitting on the wall right beside the tea-stall, sipping tea. A young girl reading and a woman mending a shoe appeared on the wall behind the friendly cobbler. A group of girls of different ethnicities could be spotted playing football on a huge wall-field. With the entry of women in the public—even if merely as caricatures painted on the walls—the streets of Khirki witnessed yet another revolution. A large section of the conservative populace of the urban village remained in disagreement with the idea of bringing women into public from the private, even as art pieces. While the barber took an active part in the process, the cobbler would remark that more women had started to come to his roadside workshop. In spite of these challenges, women started to create a space for themselves in the public. Seeing themselves on the walls, at the tea-stall, and beside the cobbler, women started to mobilise, interact, and transact freely on the streets in solidarity. To further this intervention, Revue, through these murals, also drew men on the street into a dialogue about gender equality in terms of the visibility and acceptance of women in public spaces, especially in male-associated professions. These Networks and Neighbourhoods took the shape of a Mobile Mohalla through a series of creative interactions between art and the public aimed at mapping mobility. These exchanges continue to evolve till date.

Networks and Neighbourhood 2

A modern ghetto like Khirki is a melting pot of cultures interacting and networking with each other in a myriad of ways. It is an exuberant centre of food, flavours, and heritage. With the always-migrating denizens, the site has also seen a transformation in terms of its culinary spaces and practices over the last few years with the opening up of new joints offering food prepared by both internal and international migrants. This interaction between different cuisines and multiple forms of food consumption practices has made the locality an interesting display of mutating food habits, giving the centre a new, distinct identity.

While the women of Khirki had started to interact with each other in public, the bonding between them flourished only when these interactions branched further and moved to their intimate spaces. The women, when inside their Kitchens, speak in their own unique syntax—the language of food—that they have brought along to this multicultural confluence. They are a storehouse, a living museum of their traditional cultural practices and habits. To provide a space to these stories and build a community of women, Revue launched the Living Lab. Eventually, food became the channel to their hearts with deeper personal conversations about their origins and homes often manifesting into narratives of displacement, migration, and the painful burden of nostalgia that they shared as a common heritage. These conversations continue to unfold in the public via the monthly Pop-up Kitchens. Food items—different in nature, but prepared together—are building a supportive community of women to look up to each other in testing times.

Living Lab

Some 25 Kilometres away from the emerging artistic hub of Khirki, lies another settlement of migrants in the heart of Old Delhi. Urdu Park is a barren ground surrounded with trees in the homely shadow of Jama Masjid and houses a government-run night shelter called Rain Basera. It offers refuge to homeless women and their children who migrated to the pavements of Meena Bazar seeking a better life. Women from different parts of the country who are forced to leave their families because of domestic violence, poverty, or the lack of physical, financial, and emotional security, eventually end up at the Basera. These women roam around in the markets begging for money and survive on the generous alms collected outside the Masjid’s entrance throughout the day. Their days are spent in navigating through the snake-like streets squeezed between the shiny wedding-wear shops. Unlike the women of Khirki, these women have always been negotiating on the roads. Their lives have always been into motion and their everyday relationships surrounded by an uncertain mobility. They have nowhere—no physical or social boundaries—to limit themselves within. In the abundance of such uncertainty, a group seldom bonds to create a space. When every passing moment is about fighting for fate and begging for survival, bonding is the last thing on one’s mind. Amongst their interactions under the common roof of Rain Basera, distrust, enmity, and jealousy often found home.

That is what Revue observed when they first came to interact with these women. They wanted to initiate something to pave way for bonding and togetherness amidst the chaos of uncertainties. Through Axial Margins, they explored how art plays a vital role in changing opinions and perspectives and builds up a sense of collective responsibility amongst the multiple claimants to the ‘shared space’ within the ‘public’.

It all started with diaper-making for the children at the shelter and went on to pillow-making and crafting small embroidery frames. Later on, when paints and brushes arrived, the women first painted the walls of their Basera. Then they started to map their mobility on the cloth canvases, giving space to the gallis, markets, the kind ustad who ran a tea shop, and the Lala who owned the masala shop, and also to the masala seasoning itself. While speaking of their environments through art, they also mapped the spaces and people beyond Urdu Park and their intersections with and connections to their everyday lives. Through these interactions between art and the people, Urdu Park transformed from a night shelter to an art gallery full of colours of life. Their shared masalas represented their maps, mobility, and their interconnected lives. Food, after all, unites us all.

Could Urdu Park also start a Museum of Food of its own? Revue strongly believes that Khirki’s Living Lab and Urdu Park come from contrasting contexts and would have to keep evolving independent of one another, staying true to their localities, and their characters.

Urdu Park