|

2 January 2015

The imaginary of the dialogue presents us with a paradox: beyond its inherent freedom, expression would have boundaries. Somewhere in 1532, says the etymology, a dia- was confused with a di-, and the dialogue came to be bound within the restricted setting of just two participants. No wonder, then, when 483 years later, dialogues seem to be as much, if not more, part of our problems than of our solutions. When exchanges inevitably shift to the confrontational, when an impatient statement is only calling for a louder response, we miss the fundamental understanding that a dialogue invites and includes not just the audible, forefront spokespersons, but all that a true life appreciation reveals of traditions, of cultures and philosophies, behind and between each word uttered. Yet, the dialogue between two parties seems still valid, for, a duo evokes the possibility of love and war alike. Bhakti: two makes it possible to divide as well as connect. It is the bare minimum number that we require to save us from indulgence, boredom and death. It is the elementary digit that makes a democratic dream possible. It is the insignia of the human ambition to be represented. Hence, one year ago, we made this wager, reaffirming the possibility of rigorous and engaging dialogues, responsive to the urgency of each week and translocal in the meanings created from the encounter of complementary stakeholders. To open our second year of Inter-actions, two senior artists share their dream dialogues, able to animate their fields. Priya Ravish Mehra unthreads the dialogues that join the artist across time, and those that touch communities across societies. Anamika projects listening as a key constituent of dialogue, and invites us to understand poetry as a profound patron of dialogues, as the guardian of humanity’s collective memory.

Debate

Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations.

|

|

Artistic creation seems to happen as a process. I would not see it as an outcome or a conclusion to an inner dialogue: it goes along with this dialogue, through time. In fact, it extends this dialogue across time. The common impressions of memories are the stems from which works, at various stages of life, can come to be. This allows for creation to link the present and the past.

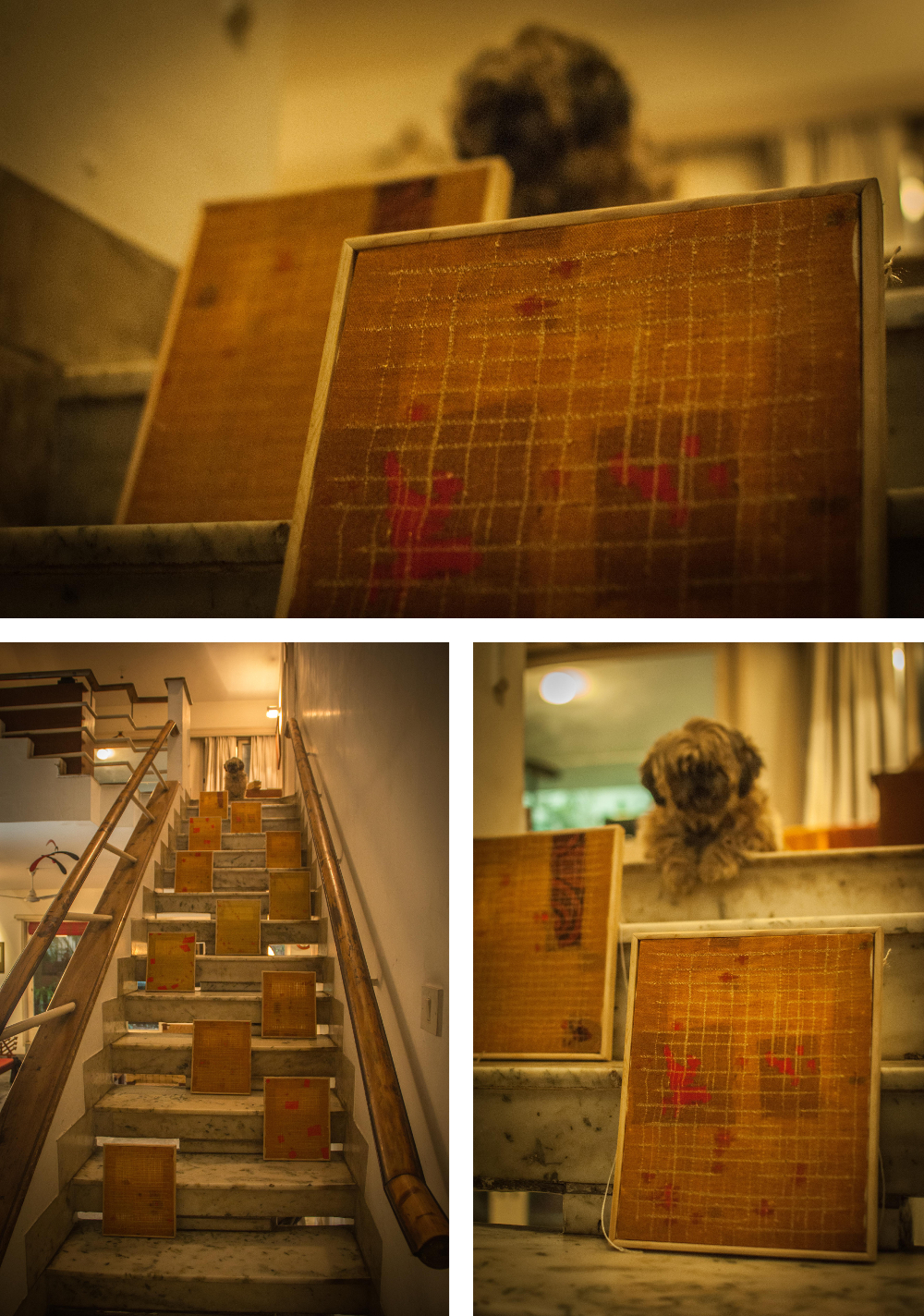

Creations tend to phase with the artist’s life. Two phases are generally observed in the body of my works. Earlier, my creations used to be much more framed, more defined. Now, the works are coming out of all that had been suppressed within me. It is more transparent, more truthful to myself. Between the two, was a phase of illness. I did not stop working on my topic, but as a practicing person, there was a gap in my creations. I studied, searched and found insights about the subject of darning. The process was at a dormant stage perhaps, not reaching expression. But it would come up progressively, into what would become my later works.

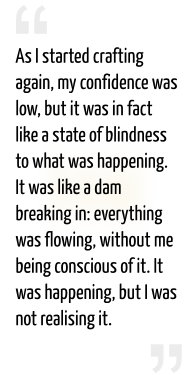

Now when I look back, the inner feelings were very much hidden under an exterior beauty. But when I started working again, the fear of death or of others’ acceptance no longer existed. I felt free to express myself as I liked, whether through spoken words or any other medium. As I started crafting again, my confidence was low, but it was in fact like a state of blindness to what was happening. It was like a dam breaking in: everything was flowing, without me being conscious of it. It was happening, but I was not realising it.

Leaving the threads visible

My later works show the threads visible, unhidden. It is while darning, mending clothes, etc. that I encountered the decision of either camouflaging or revealing the defects. This whole metaphor made a kind of mark on my new work. I came to understand: if there is a defect, let it be. Defects, once revealed, can acquire a new strength as one adds more to them. That is probably what life is about: we are vulnerable in various situations, but we go on strengthening ourselves, acknowledging and recognising those gaps, those weaker moments, those damages. Thus, you go forward with your work and your life. One can get conscientious of the very fact of putting one’s works in a public space: is it perfect or not? It does not matter to me anymore: beyond art, those visible defects are the truth of what happens in life. One is still very much there with all the imperfections – still there, celebrating life. Then, creation and life are not even corresponding to one another: they form a whole.

When the specific material medium does not matter, life becomes the medium itself. And the dialogue can happen only when all the different stages of work come together in a conversation: research, documentation, and the work of weaving itself. It is a dialogue at an individual level first, but it is indeed going out of oneself, taking place with others, and ultimately, across the cultures of the world. But this is not the ultimate destination. Creations may reach a global audience, a large reception, but they must bounce back to the local context. Sometimes, local issues are talked about at an international level, but this does not make a difference to the local. How does the local environment react to this awareness? Does it respond to it at all? The process of creation is coming out of a turmoil within me, and it comes back to me through this reception. In the same way, local issues must also, as they reach a global context, create a turf, back to the local, to make a difference.

Beyond individual initiatives, art can indeed facilitate dialogues, but on the condition that we gain clarity as to the nature and becoming of craft traditions today. Artisans are invited to show their works in exhibition spaces, or to prepare their crafts for touristic events, rather than catering to the people of their localities. Things are going to change, and we must get ready to accept those transitions. Many traditions may carry on, or just die of their natural deaths. But it will not be sustainable, in any case, if the effort is made from outside. Only initiatives from the communities, from each system, can work. The crafts and skills have their own strength to exist. I often tell the example of this village where we went. There were two craftsmen. One was willing to go by what we suggested. The other refused to do it, saying that the minute he goes with us, he would lose his local clientele. Once this is lost, the natural death of his craft will not be far. The work brought from outside, imposed on him, produces a short-term effect.

Through the years, I have been involved with many textile people from various parts of the country. Every time, there is something to learn from sitting with them. One question is still puzzling me, however: what do we give them back? What do they gain in return? I came to realise that recognising the process of their work, valuing their work and appreciating their self-respect is the least they must get in return. The work, made by hand, has to be valued.

Art and Life

This respect for their occupation is fundamental. An occupation, indeed: those craft-makers had, for a very long time, nothing to do with art, with aesthetics. These were the occupations of a people. There was a function, a meaning behind each thing created. The minute we use the object for another, outer purpose, its initial meaning is gone. As a designer, I was confronted to this issue: I would go to the field, documenting different crafts, various textiles, to understand what they were meant for. But once you bring a design or a motif elsewhere, for another purpose, its meaning is lost. You cannot use a motif for bath towel when it was initially designed for a ritual practice in a temple! This requires local-based knowledge. In Gujarat, wool is considered as pure. It is a local resource. But in Bihar, silk is the pure material. It is used in temples. The same material acquires different meanings and values across spaces. When looking at the craft with outside references, we lose its meaning.

One remembers Gandhi’s philosophy on production: making clothes from one’s own people, in order to make the tradition sustainable. When outsiders come and try to set up an artificial ventilator, there is always a risk to pull it off. If the workers can breathe on their own, with their own strengths, death may happen, but then it will be a natural death. This is beyond textile: this is the reality for terracotta, for wood, for metal and other materials. It is a story of sustainability and survival.

|

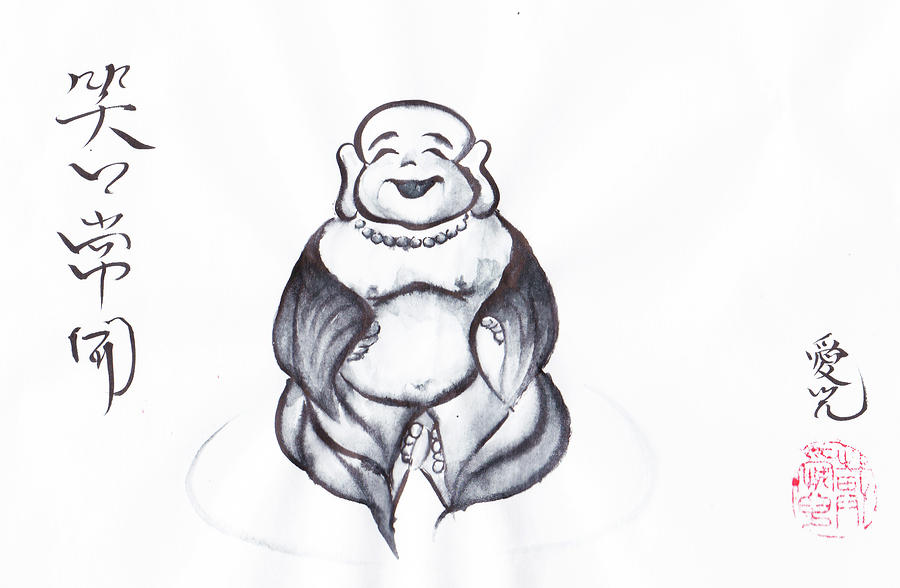

Asian, German, Greek, Latin, African and Latin American philosophers today seem to be agreeing on at least one point: there is a constant interplay of opposing factors or binaries both in the outer Nature and in human nature, factors such as permanence and mutability, tranquility and emotion, harmony and discord, law and impulse, unity and variety, ideal and actual, the empirical and the intellectual, and a midpoint must be achieved in the subliminal space between the binaries. This midpoint, possible only through a dialogic recreation of reality, finally leads us to equipoise, a ‘samyak dristi’ or ‘sthitpragnata’ essential for a dignified survival in this hyperactive world of public and private breakdowns.

Scientists, too, have reached the consensus that there is a unique zone of harmony in the heart of every atom, which stages a never ending dance of protons, electrons and neutrons within an apparently still surface. Underneath your super-serious face might be sealed the ripples of a laughing Buddha.

The ripples…

The English Romantics, seasoning their influence of Hegel and Schiller in the heat of Industrial and French Revolutions, talked of the degrees of mutability, tranquillity, etc. in different orders of being and they dreamt of a state where the ‘joy of one becomes the joy of tens of millions’ (सर्वे भवन्तु सुखिनः?). These pilgrims of Beauty, Liberty, Equality and Fraternity found, “benevolence and blessedness/spread like a fragrance everywhere” (in the words of Wordsworth).

But the greatest tragedy of human life is that these chances of liberty fade away along with the daffodils and visionary gleams of the early childhood, when the Napoleons, Hitlers, Neroes and Saddams take over, censuring not only the interpersonal but also the civilisational dialogues of all kinds.

One of the major charms of our post-modern times lie embedded in the essentially democratic and non-authoritative venture to slash off the claimed hierarchy between binaries. It promotes an intertextual dialogue not only between the personal and the political, the sacred and the profane, the classical and the popular, the East and the West, but also between classes, castes, genders, races, locales and time-zones. Aptly summarised as the ‘romance of the marginalised’, the post-modern world actually lays a mat for all the binaries in the world to sit together and go on chatting like eternal ‘sakhies’, to resolve one set of differences and proceed to another.

Patient hearing is a must for a meaningful dialogue. Poetry is all ears and all eyes not only to the sound bytes but also the various visuals that come floating by like aborted babies in the turbulent sea of human conflicts. With the patience of a mom and the friendliness of a teacher, poetry not only nurses these orphaned bytes and visuals but also makes them sing and dance together in the vast space of sense and nonsense.

In literature and sibling art forms, at least, thoughts enter like a ray of light. Light does not transcend material objects nor does it strike them and bounce them off. It gets caught up in things. Intertwined with objects, refracted and tinted as ‘starlight’, ‘green light’ and other kinds of light, it spreads cheerily, entering into a meaningful dialogue with one and all. Artists, at least, know that all objects on the earth are dangling in the twilight zone between being and becoming. The whole philosophy of a gap between ‘what we are’ and ‘what we want to become’, or are ‘destined’ to become, sets the ball rolling everywhere. Great writers of all times believe that a dialogue between binaries negotiates its motion in the right direction. Tagore, Eliot, Rilke and Paz hint not only at vibrant civilisational dialogues, but also at a meaningful dialogue between all forms of knowledge and all sources of wisdom within each civilisation.

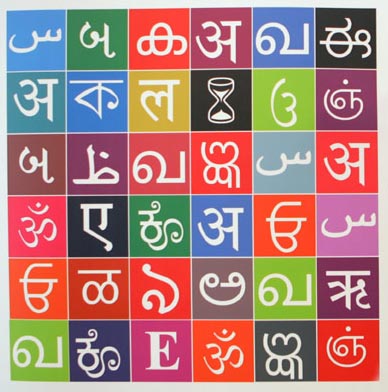

Across and beyond the ‘bossy’ languages in India

To quash the hierarchy between the ‘bossy’ link languages and the rest, link languages must set the roles of an errand boy and a sutradhaar. Instead of bossing around, both English and Hindi should keep running from one language to the other, organising translations and bhashyas (running commentaries) of both the ancient classics and the best in the contemporary writing of each and every Indian language. Geeta Dharamrajan (Katha), Ambai (Sparrow), Ritu Menon (Women Unlimited) and Urvashi Bhutalia (Zubaan) have played a great role in linking up. The Sathiya Akademi journals too have kept us somehow connected. In the fields of poetry and drama, much remains to be done. The National School of Drama and other such organisations should stage not only the best of Indian fiction but also the best of Indian Poetry at Community Centres and Panchayat Bhawans, and these enactments could be later both broadcasted and telecasted on prime channels.

Terrorists detest dialogue. They ridicule all attempts at dialogue as ‘status quo is bullshit’. They think that dialogue can only result in reform, and that reforms are at best a healing balm to soothe the fractured contours of our world without dealing with the source of the fracture. The argument is strong and cannot be dismissed in a jiffy, but forces of history highlight that there is nothing called the ‘ultimate cure’ in life. Diseases are multifactorial and the cure, too, can only be dialogic. The market forces are against them, and yet all forms of alternative medicine have survived till date. Nothing in the world can be really wiped out. Residual philosophies are all the time negotiating with the mainstream.

Joining hands together, even mini-narratives can fly high. Remember the pigeons in the Panchatantra. Caught up in the hunter’s net, they all felt so helpless till Chitragreeva, the senior pigeon, came up with the brilliant idea of applying the joint force and flying together with the net held between their claws, winging across the river where the Ratking Hiranyak with his friendly set of sharp, little teeth awaited to release them from the net. Similarly, the joint front of sibling art-forms, literature, painting, music, architecture, sculpture, etc. in a unique forum like LILA, can also help us fly high, with the ‘net’ flying along Chitragreeva’s guidelines.

|

|

Priya Ravish Mehra is a textile artist and weaver, researcher and designer based in Delhi. She is the creator of New Delhi Residency, a space to facilitate partnerships and cultural exchange for artists visiting India working in various creative mediums and disciplines. She has presented her work and research at various events across the world, and she organised several textile events in India. A graduate from Visvabharti University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, she studied weaving at the Royal College of Arts, London, and the West Dean College, Sussex. She is co-author of Saris of India: Bihar and Bengal (1995) and research author for Saris, Tradition and Beyond (1993).

|

|

Anamika is a Hindi poet based in Delhi. A lecturer at the Department of English at Satyawati College, Delhi, she has five collections of poetry to her credit. Over the years, she has won numerous accolades for her literary work, including the Bharat Bhushan Award for Poetry (1996), the Girija Mathur Samman (1998), the Sahityakar Samman (1998), the Parampara Samman (2001) and the Sahityasetu Samman (2004). In addition to poetry, she has authored volumes of fiction, memoir and criticism, and undertaken translations of the works of Octavio Paz, Rilke, Rabindranath Tagore and Girish Karnad.

|

|