Life and Art of P.R.M

The weaver, getting good or bad yarn and connecting karmas with it, weaves beautifully.

– Kabir

Priya Ravish Mehra weaved beautifully, connecting different karmas, mindless of whether the yarn given to her was good or bad. As a haptic artist and designer, she was an unmatched promise, a relevant thread of connection, given to our world in these divisive times, the fulfilment of which is now left to everyone who came in touch with her many-splendored life.

‘Thread’ was indeed the word that took me to Priya. She was part of a group show, ‘Threads,’ at Alliance Francaise, New Delhi in 2014. I was at that time evolving the concept of Terra-Sutra (‘thread connecting the world’) which has now become the umbrella of LILA’s activities. My colleague Satchin chanced to see the exhibition on the last day and told me that there was an artist whose work with ‘threads’ might be relevant to Terra-Sutra.

The idea of an artist working with ‘threads’ was so alluring, I decided to meet her. When I rang her, Priya readily said, “Come home, the works are all here!” Without deliberating, with that infectious laughter and welcome in her voice. The connect was instant.

When I drove to 14 Sultanpur Estate the next day, I never thought it was going to be what it became between Priya and all of us at LILA. I vividly remember sitting outside with Priya, listening to the many marvellous sounds of birds and other lives from her garden, sipping coffee and munching on some farsan, talking endlessly and laughing all the way. It did not feel like a first-time. And, of course, we would recreate that scene and relive that feeling so many times over the years, after that day.

What strikes one as remarkable about Priya’s work is the organic way it evolved. She let time season her thought, material and practice, and watched with a sense of simultaneous wonder and understanding the incomparable artistic forms that came out of her own multi-dynamic spaces. And, she generously shared her work’s processes as well as her ideas, all lit up by her creative curiosity, with everyone who came her way.

Priya hailed from Najibabad, once the old kingdom of Rohilkhand in western Uttar Pradesh, which had its own resident community of rafoogars (traditional darners) and a long history as a hub of the trade in kani pashmina shawls from Kashmir. Her parents were artists and professors at Visva Bharati University in West Bengal, and collectors of textiles and art. Weaving and rafoogari thus remained two native threads in Priya’s life, connecting all the later evolutions of her personality, and giving keen insights into the repairing and healing processes that her life challenged her to adopt from time to time.

Given her background, it was natural for Priya to opt for a fine arts degree in textiles. But what was extraordinary was her insistence on learning weaving, for which there were no specialist teachers at Santiniketan at that time; she found a way to learn weaving from practising masters outside the walls of the University and convinced the authorities that she would manage to cover the syllabus on her own. And she did.

That spirit of adventure and a quiet-yet-powerful exploration of possibilities were characteristic of Priya Ravish Mehra — as human being, thinker, artist. After learning to weave at Santiniketan, she worked as a research consultant for Indian handlooms and handicrafts, and from 1987-92 she travelled extensively through Bihar and Gujarat with her brother, designer Tushar Kumar, documenting local textile traditions for ‘The Saris of India’, a major national research project sponsored by the Development Commissioner (Handlooms), Ministry of Textiles.

Priya’s engagement with various Indian weaves encouraged her to connect with weaving traditions in other parts of the world, andshe went to study tapestry weaving at the Royal College of Arts, London and West Dean College, Sussex, UK, under the aegis of a Commonwealth Fellowship and Charles Wallace Trust (India) Scholarship. During this intensive phase of understanding textiles and weaving methods across borders, Priya recovered the idea of ‘connection’ as an important motif in her artistic work, and her textile and mixed-media works were featured as solo exhibitions at British Council, Delhi (1993); Commonwealth Institute, London (1994); Harley Gallery, Nottingham (1994); Eicher Gallery, Delhi (1997); Jahangir Art Gallery, Mumbai (1997). She participated in many group shows: ‘Weavers of the Pacific Rimʼ, Taumata Art Gallery, Auckland (1993); ‘Palash’, Rabindra Bhavan, Delhi (1997); ‘Dedicated to Mother Earth’, British Council, Delhi (1999); 10th International Triennial of Tapestries, Lodz (2001); and ‘Resonance’, Rabindra Bhavan, Delhi (2005). She also co-authored Saris of India: Bihar and West Bengal (Wiley Eastern Private Ltd, National Institute of Fashion Technology and Amr VastraKosh, 1995), and continued to bea researcher for Saris: Tradition and Beyond (Roli Books, 2010) for which she worked with veterans such as Rta Kapur Chishti and Martand Singh.

Priya travelled among various textile traditions and explored ways to incorporate rare weaves into her artworks and designs. Not many people know that some of the well-liked Fabindia designs were created by her during her time there. She was showing immense promise as an artist and a designer, and her abandon matched her potential.

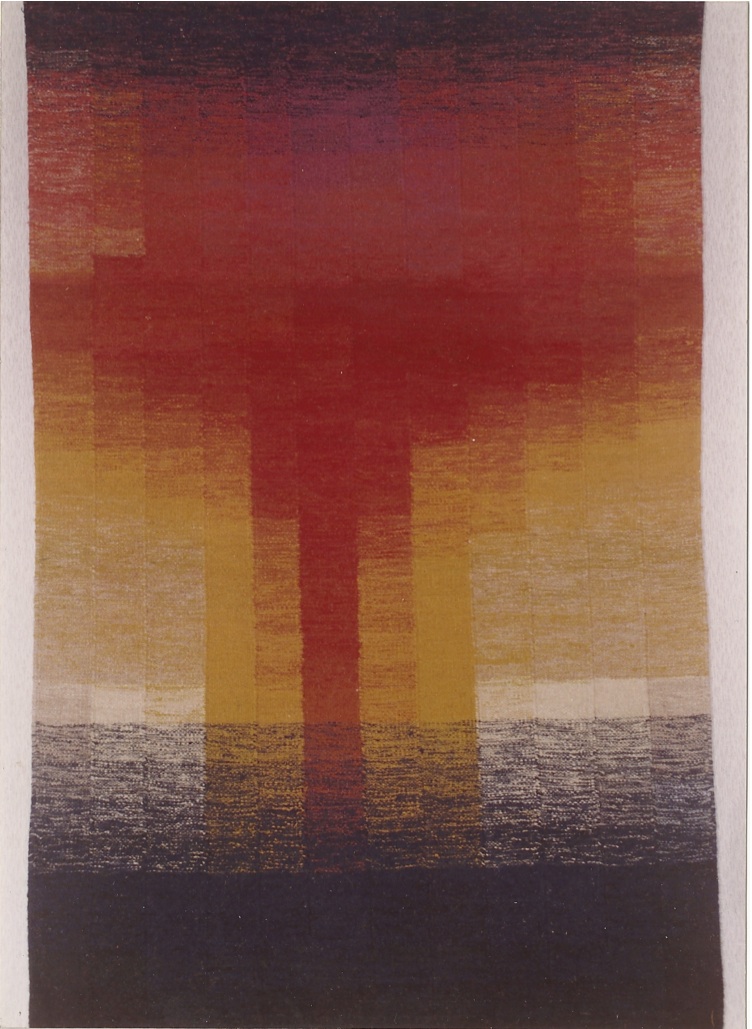

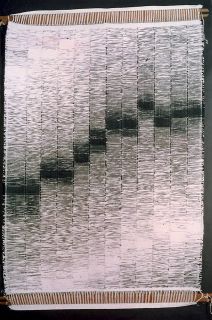

Three early tapestries: Full Moon; Solar Calendar; Lunar Calendar

But Priya had yet another calling to attend to — which came to her from her hometown Najibabad. And that call appeared in her life like a thread of healing connecting life and death. Priya was diagnosed with advanced cancer when she was just 44. She went home to Najibabad to recover from the trauma of frequent radiations, to give some solace to her affected body. And that was wherethe stark parallel between the native rafoogar’s work of repairing old fabrics and the processes that must heal the fabric of her own life occurred to her like an epiphany. The realisation that one cannot throw away the old and the battered if they are precious to one, steered Priya into another intense journey, artistic as well as existential. She began to reassess the notion of ‘imperfection’ and saw that no claim to modernity was valid if it attempted to construct a false sense of perfection and independence, decrying its past, camouflaging its seen and unseen wounds.

The insight that helped her rediscover ‘rafoo’ as a metaphor of healing was a turning point in Priya’s life and artistic career. Her studies on the history of rafoogari revealed that this community of cloth healers had been a rather invisible one. Like a good editor’s work, the best rafoogar’s work did not show. Age-old royals as well as game-changers in the market came to them, sought their work’s ‘perfection’. But, neither the claimants of vintage nor the proclaimers of development wanted to acknowledge the presence of the rafoogar in making time stand still for them. The rafoogars functioned, an unseen presence bridging time, among the proud heirs of many elite families as well as in the factories that made big clothing brands. Like their darning, they too remained invisible, unable to claim their rights either as workers or as artists.

Priya wanted to illuminate the role and reality of these unique artisans, and embarked on her landmark project on the rafoogars, ‘Making the Invisible Visible.’ As she began acknowledging the multiple factors — people, places, material, methods — that aided her own healing, she saw a way to speak about the rafoogars too. She began working with them, doing workshops with them in urban spaces, speaking about them, taking them beyond the borders of their small towns.

Priya received the Asian Cultural Council Grant to study the maintenance and preservation of Indian textiles, especially the Kashmir shawls in Public and Private Collections in the U.S.A. Her project led her to a three-months’ arts residency in Scotland, with Cove Park and Deveron Arts, Huntly. She presented her papers “Rafoogari of Najibabad” at the 9th Biennial TSA Symposium in Oakland, 2004, and “Rafoogari – An Invisible Craft” at the North American Textiles Conservation Conference in Mexico, 2005. She participated in the “Common Goods” Project along with Indian rafoogars at Ballarat Fine Art Gallery, Australia, to restore and recreate the Eureka flag during the Commonwealth Games in 2006. She organised Rafoogar Baithaks at Sanskriti Kendra, Delhi in collaboration with INTACH in March 2009; at ‘Raksha’, a Textile conservation conference at a ‘Sutra’ event in Kolkata in February 2010; at Murshidabad Heritage Festival in December 2011; at C-13, FICA Delhi (2017) and at Max Hospital, Delhi (2017). She participated in “A Darning Trend”, Slow Fiber Tour, Tokyo / Arimatsu / Kiryu (2010); and “Invisible Darning” at Future Australia, INTER:ACTing: Participatory Design, Venice (2011), and in international Shibori symposia in Japan (2005), China (2014) and Mexico (2016).

After I met her, and learnt of her incredible work, LILA organised an event to celebrate her work in 2014. She named the event ‘The Imperfect Cloth’ and articulated to us her vision of inclusiveness, her dream of a world that acknowledged the past, healed the present and created for the future. At the event at the India Habitat Centre, with musician Minakshi Thakur singing the legendary weaver-mystic Kabir’s reflections on the fragile fabric of life and dancer Parash Moni Dutta dancing to those tones, I conversed with Priya and her long-time associate the Japanese artist and curator Yoshiko Wada, about the analogous worlds of rafoogari and Japanese boro. They talked about ‘the imperfect cloth’, and the need for relevant reclamations in our time, to an eclectic audience that included Priya’s healer Nicholas Packard, who miraculously arrived there from his globetrotting; her doctors, the rafoogars with whom she had been working, her friends and associates from the Santiniketan days, and a lot of others too. That evening showed us the spirit of Priya, opalescent in every sense; we saw the many-hued yarns that she had extended to connect with spaces far beyond herself.

Later, during 2015-16, when I was Creative Director of Indian Languages Festival Samanvay in New Delhi, I requested Priya to join our team as Set Designer, as I wanted to avoid/reduce the use of flex on the stage and elsewhere on the India Habitat Centre campus. That was when I received my first-hand knowledge of how Priya incorporated the profound lessons she had gained from years of weaving and rafoogari work towards creating an altogether refreshing art space, a new aesthetic, a radical perspective on self-governance for this country.

I saw the backdrops she created for the festival and realised that she was taking weaving to a deeply ideological level and making it a powerful tool of communication, as potent as or more transformative than any of the speeches or acts that were to be delivered on the stage. She was not just making some nice-looking sets; she was shaping a parallel language that interacted with the socio-political and cultural aspirations of the festival. She was illustrating a new use of cloth — it was not only to cover and protect your bodies that cloth must be used in these rather brazen times, but also to reveal the colours of your true sensitivity.

It was an eye-opener. I saw what an indomitable warrior and how profound a political subject she was, not just an artist. Her cancer had further advanced by then, and her weekly chemotherapy rendered her very tired. Nonetheless, in those days it was always to Priya’s place that we went to take a break from our work. She touched us all with her immeasurable grace, wit and humour, and made us forget that cancer was consuming her, and that she was in pain. And, remembrances abound. Early winters were always a good time in her garden. She made a lot of pickles from all the things that grew in her garden at Chattarpur and her farm in Gurgaon, and tried out many curious recipes gathered from across the country and the world during her travels. We ate, drank and were so merry with her. But we also thought, spoke and did significant things with her — those things, the relevance of which we are fully aware of now when she is no longer with us to laugh and learn with. Through all this agony and ecstasy, she not only attended all our team meetings but also produced, in a little over a month, an incredible number of big public art works to form our sets, and put together her own solo show ‘Visible/Invisible’ at the festival, which we featured at the Experimental Art Gallery of the India Habitat Centre.

That was tremendous effort Priya had put herself through, all out of love and for free, the implications of which were path-breaking. While it gave her a sense of direction and inspiration to fight on gracefully, Priya astonished us as she weaved coloured strips of cloth into military camouflage nets and used them as backdrops for our main venues. At the amphitheatre which was the main venue of ILF, we had her stunning works of art as the setting, an unprecedented language reminding us about the histories and peoples that had long been marginalised and rendered invisible, and the urgent need for them to be included in our academic and public discourses, in all their tones and shades. She so beautifully subverted the violent history of the camouflage net, by telling us not to use it to cover ourselves from any enemy, but to blossom out in all our hues.

That transcendence was the most valuable lesson of survival that we received from Priya. Her works showed us how to walk between the poles, reducing the distance between them with our pace and intent, and a vision of the full circle. The four main trajectories of her work would reveal an incredible crossing, a marvellous bridging of apparent opposites.

Weaving beyond Opposites

Priya’s symbolic early woven works as well as her studies in sarees and tapestry do not negate the practical motif of cloth as ‘cover/protection’. The theme of connection that animated all her engagements with ‘yarns’ took her to different stories and storytellers in various parts of the world. She became keenly aware of the compatibility of threads. And, after she rediscovered rafoogari as a seminal metaphor of conservation and a way of articulation, her art too came to be informed by that insight, and underwent radical shifts in its intent — it became a mode of revelation by the time she created (In)Visible for ILF. Three decades of her artwork would show how she nullified the concept of opposition through her unending pursuits — somewhere along her path, the fear of exposure and danger gave way to the joy of revelation and creativity.

Mending towards Healing

Priya’s interaction with the rafoogars has been a long one, continuing till her last days. She did many Rafoogari Baithaks, and engaged herself in a lot of experimental work to master the ‘invisible art’. She collaborated with the rafoogars of Najibabad as well as well-known artists and curators like Yoshiko Wada with the same ease and fellowship, and created collaborative workshops on cloth-healing activities, including the Japanese boro technique.

Priya at Rafoogari Baithaks in Delhi with the darners of Najibabad

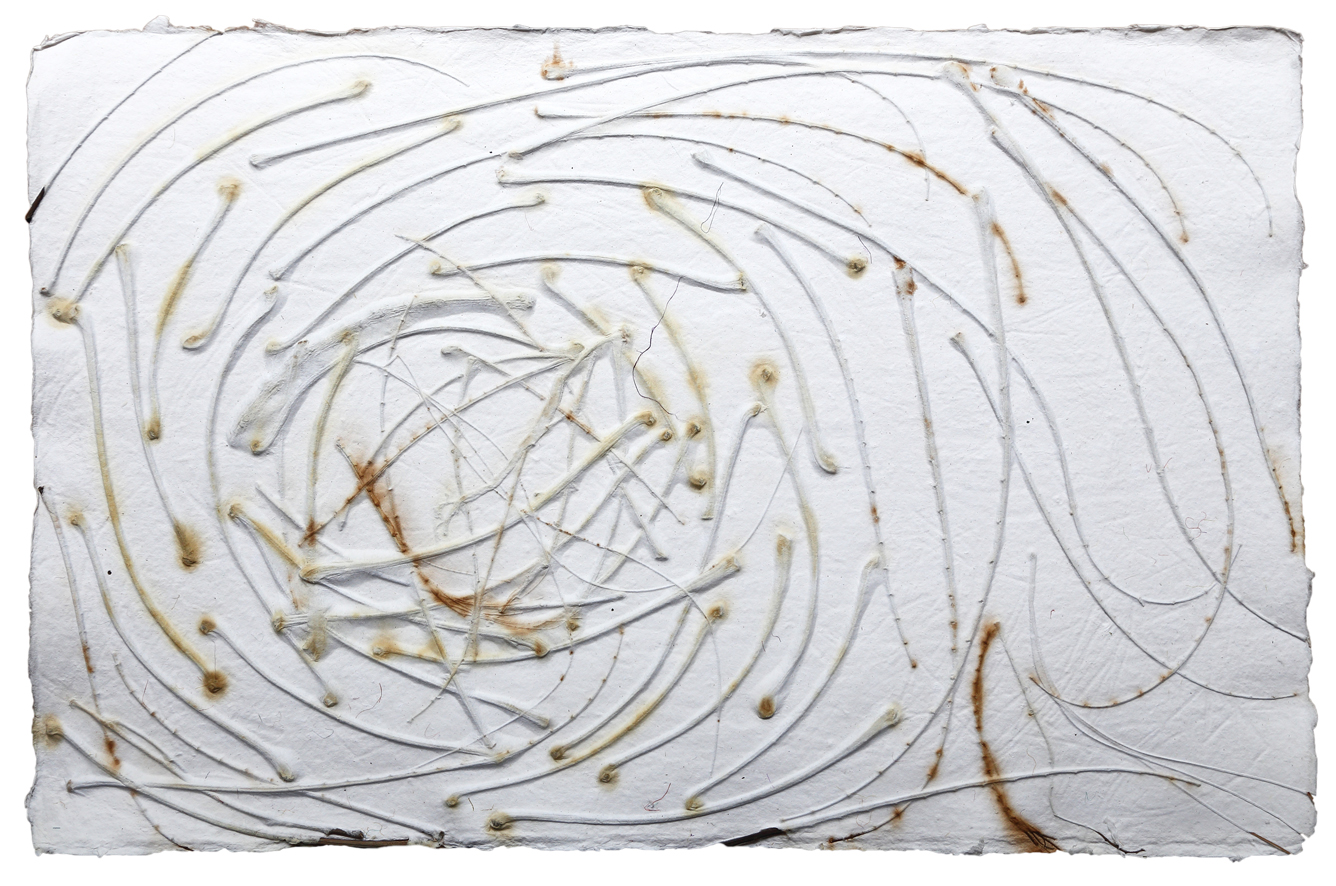

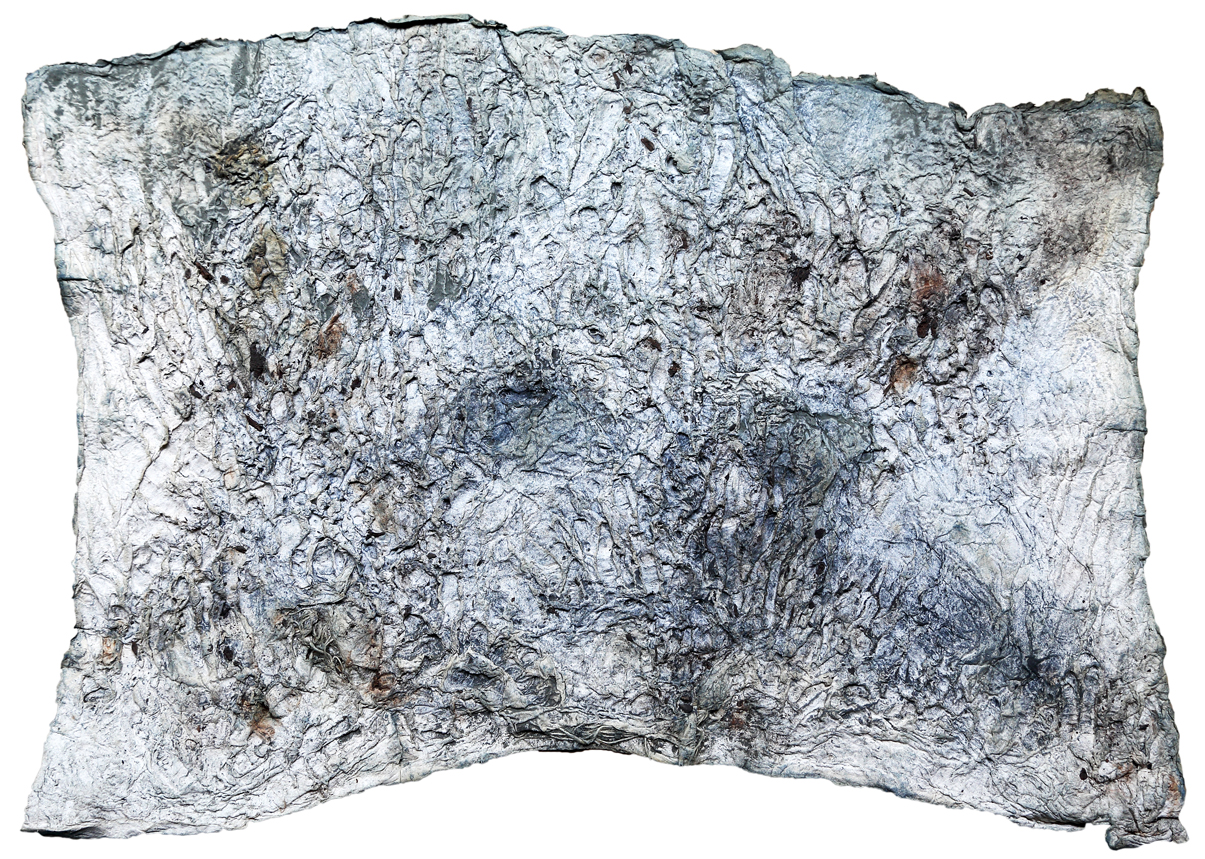

Priya’s research and documentation on rafoogari was being prepared for publication. Her editor Smriti Vohra worked closely with her to put the first draft of the book together, and her close friend Amba Sanyal was in conversation with her to write a fitting foreword. When this resonant work is published, it will open a creative way to reclaim the lost ties between tradition and modernity, livelihood and artistry, research and fellowship. It is through her discovery of the deep connection between apparent opposites that Priya realised the need to make visible the threads that darned a cloth so perfectly. And, she began a new search for ‘not-so-perfect’ material that can show the threads unabashedly. Her mixed-media frames during this phase of work showed threads coming out of different textures and material — rags, print, paper pulp. And, as time passed, the threads became different, too—all sorts of organic material including dried coconut flowers, banana fibres, husks, and anything interesting that she found on the road.

Fibre/mixed media work / Priya with textile scholar Yoshiko Wada

Priya’s concern about the compatibility of materials attained a meditative quality towards her last days, and it impacted her gardening, farming and cooking as well as her approach towards her cancer treatment. She became more open and exploratory in all these areas, and her researches connected her with people and resources from multiple disciplines. All her external engagements helped her evolve and develop a quiet confidence which brought a certain healing and a sense of calm. She knew that there was the reward of peace in acknowledging and appreciating all that came one’s way; everything helped her flow and irrigate many a dry terrain along her course.

Long Live Dyeing

Priya’s association with Yoshiko Wada and her coming in touch with the practice of shibori, the Japanese dyeing technique, converged with her thoughts about and engagement with natural raw materials, organic farming and alternative healing therapies. The result was multiple experimentations with indigo planting and dyeing. I remember going to her place and finding her in excited states as her indigo fermented in a vat. Some other times she would recklessly take out a fine papier-mâché work of hers, and with a fearless abandon that only true seekers are capable of, dip it into a freshly decanted filtrate. Once, when she demonstrated this at a workshop at Khoj, Yoshiko joined in and with her expert hands placed some newsprint over the drenched artwork lying on the floor and started dancing on it. That was the ‘indigo dance’, she said — a technique they used in Japan to ensure that the indigo dye seeped deep into the fibres. Priya watched Yoshiko’s dance on her artwork and laughed and cheered her. She was always ready for experiments, never afraid of things going wrong, ever willing to welcome the different shapes and colours that time alone could reveal to her.

Mixed-media works using indigo dye

Stories Meeting the Yarns

By the beginning of 2018, Priya’s cancer began to really pull her down. One symptom was serious jaundice that affected her liver. She was in pain, but there was also an urge in her to keep working. The world was beginning to see her works and understand their significance. Most of her art was now using indigo dye and organic fibres. Her solo exhibitions featured her rafoogari-inspired works: Invisible Cloth, Instituto de Artes Plasticas, Mexico (2016); Presence in Absence, Gallery Threshold, Delhi (2017) and Journey of a Shawl, India International Center, Delhi (2018). She also participated in many group shows: ILF Samanvay, India Habitat Centre, Delhi (2016); ‘Poetics of Plurality’, Baroda (2016); ‘Evidence Room’, KHOJ, Delhi (2017); C-13, FICA, Delhi (2017); ‘Monsoon Chapter 12’, Art-Centrix, Delhi (2017); ‘In-Between’, Korean Cultural Center, Delhi (2017); ‘Detritus’, Serendipity Art Festival, Goa (2017); ‘Verdant Memories’, Gallery Threshold, Delhi (2018); and India Art Fair, Delhi (2018).

Committed to socially engaged art, Priya had earlier taught weaving in educational institutions, and her work with NGOs included a rehabilitation programme for the female inmates of Tihar Prison, Delhi. Now, while still able to travel, as an International Design Consultant for the national READ (Rural Education and Development) programme in Bhutan, she worked with community groups engaged in traditional weaving, the ideal of happiness that is part of Bhutan’s national mandate moved her no end. She longed to go back there again and again. She returned from one such trip with a few pieces of daphne bark which she had gathered during her walks in a Bhutanese village, and casually started teasing a certain fibre from the moistened wood. What started as an impulsive act soon became a therapeutic mediation for her, and through her meticulous handling of this remarkable material she produced wondrous works of art, which went on to become an art installation in her solo exhibition lovingly displayed by Prima Kurien and curated by Tunty Chauhan, and so evocatively titled, Presence in Absence.

Priya was getting more and more interested in exploring the correlations between forms of human language and natural materials. She had begun weaving scripts into her works and wanted to link the traditional dastangoi form of storytelling with her rafoogari-based work. Curators Anita Dube (Kochi Muziris Biennale 2018-19) and Salima Hashmi (‘Pale Sentinels: Metaphors for Dialogues’, Aicon Gallery, New York, 2018) saw her works and wanted to feature her in their themed shows. Priya was working closely with her associates to deliver the works for these exhibitions. If life had let Priya be with us still, she would now be in New York, attending Salima’s show. But time had other plans.

The ideation-practice-research triad worked like a magic wheel in Priya’s projects. She hardly did anything without deep introspection and research. But her processes did not weigh her down or make her practice heavy. Her exploration of multiple fields of knowledge and creativity indeed set her free and rendered her wise. She came directly from the hospital to the Kaapi LILA conversation on ‘Language and Public Space’ that we

As we carry forward Priya’s ideas and facilitate discourses and interventions that might some day lead to the formation of ‘unperfect societies’, to draw from Milovan Djilas’ title, we see that for her ‘not being perfect’ was a welcome idea that nurtured cultural diversity and inclusiveness in a country such as India. It helped one see the human being as just one part of multi-centred nature, and not its only point of reference. Her dealing with cancer reveals a lesson to us: the body is a renewable site that needs to be constantly healed and re-understood, and in the context of artmaking, renewability acquires critical significance.

Mixed-media works with Daphne fibre (left) and cloth-paper pulp

Priya’s last set of works were proof that she was concerned about language. Her art now showed words struggling to come out of cover, trying to articulate, striving to overcome stammer and reclaim the secret of communication. This series of works were integrally connected to her appreciation of rafoo and the way the rafoogars gathered the yarn, selected the most compatible threads to cover the damages on the cloth given to them. She saw and depicted the parallel between a rafoo made from different threads and a linguistic utterance containing various parts of speech all combined into relevant meaning. She saw the possibility of understanding language as a curated artistic experience that can communicate love and hope to individuals and communities during divisive times. Her works articulated the need to be self-reliant and not yield to any external imposition of perfection. Against all power-play and political manipulation rampant in this world, her art still upholds the dream of an ‘unperfect swaraj’ where people do not evaluate themselves with reference to their perceived ‘other’, but appreciate themselves by their own textures as well as capacities to walk from pole to pole, to nullify opposites, to evolve constantly, to remain translocal, like Kabir’s fragile piece of cloth — jhini jhini chadariya….

Images: Monica Dawar & Priya’s Archives