In the Changthang valley of Ladakh, at an altitude of 5000m, sitting within the warmth of a Changpa nomadic tent, I experienced a living museum. Every element of that dwelling, from the laying of stones to the arrangement of space and items within the small enclosure, reflected refined aesthetics and valuable knowledge. I was amazed to know that the hand-woven yak wool tent within which I was sitting along with the children of the Changpa community was rain and wind proof, and yet filtered sunlight in through its weaves — something I couldn’t have imagined even in the most technologically advanced tents.

I learnt that their traditional practices were based on zero-waste concepts. Through a symbiotic relationship, they meticulously nurtured the surrounding environment for a mutually rewarding future.

It made me wonder why we struggle so much today to find good examples of sustainable living. Why were such valuable knowledge resources and practices of our country fast disappearing? What was the reason for the youth of these communities to remain ignorant of the importance and contributions of their own traditions and cultures? What holds them back and alienates us from easily adopting and learning from these outstanding examples?

Was it a problem of archiving? That thought made me reflect further on the many public archives that we have – how and in what format can they be accessed and by whom? Furthermore, what are the subliminal barriers and limits of such accessibility?

According to the Educational Statistics report released by the Ministry of Human Resource Development in 2018, India’s overall literacy rate was approximately 69.1% (both in urban and rural context) in 2014. So how many people could have reached even the publicly available archives, collections and portals that showcase different types of knowledge?[1] The process of sharing knowledge remains stagnant within museums, collections, libraries and institutions. Unfortunately, our archives exist in a pseudo-public domain. The questions of authorship, anarchy, and control are the complexities that lead biases to frame the histories of humankind today.

Encircled with these intersecting questions, enquiries, experiences and realisations, I felt the urgency to conceptualise and develop a platform that would travel across boundaries, cultures, traditions, and communities, to foreground everyday practices, raise awareness of a particular socio-spatial reality, bridging the past to the present, and adding value to create future opportunities through collaborative, co-produced living archives and art practices. Thus, ‘Disappearing Dialogues’(dD) was born.

dD is an attempt to play a catalytic role in connecting ends. The case studies of three of its archiving projects in three different parts of the country – Ladakh, Baghelkhand and Bundelkhand, and the East Kolkata Wetlands – may reveal how opportunities could be created for the future generations by restoring the past and revitalising the present.

Ladakh: The Climate Crisis and More

dD’s research and documentation in Ladakh identified the crisis evolving in the region due to rapidly melting glaciers, loss of habitat, water shortage with climate change. Young nomads have for some time been adapting to other occupations while concrete housings have been mushrooming due to indiscriminate tourism practises in the region. Against this backdrop, dD archived a treasure trove of medicinal and aromatic plants along with the unique ancient culture of the nomadic Changpas and their valuable zero waste practices and principles of simple living. The project’s creative interventions aimed to instil pride and voice within the youth we worked with in Ladakh. With the children of Nomadic Residential School – Puga, we co-created a small pop up museum on nomadic culture and heritage along with a playfully geo-choreographed live performance.

Our collective realised that the abundant traditional and ecological knowledge, cultural experience and creative skills of the rural population can help them co-create an archiving system that could bring pride, self-empowerment, and create opportunities for youth of the community. Towards making this a reality, dD embraces art as a universal public language of research, preservation and dissemination. It looks at art as a situated, embedded practice that enables an alternative mode of learning about individual and collective socio-cultural identities. It also makes possible trajectories of socio-spatial activism deeply rooted in a dream of transformation.

Designed as a sequence of collaborative, participatory processes, it creates a living archive whose beauty lies in its co-creation and multiplicity. Thus, exploring notions of everyday practises and the importance of collective engagement, it creates varied narratives of associations and interpretations, widening circles of access for the public. Rather than taking a developmentalist approach of top-down interventions, the processes are structured to build on existing and emergent community assets including skills, local knowledge, cultural practises, history and heritage, natural resources and networks. Through collaborative art, performance, installations, workshops, exhibitions and DIY activities, this project tries to demonstrate the intrinsic strengths of the people to co-create possibilities.

Baghelkhand and Bundelkhand Region: Tangible and Intangible Heritage

In the Baghelkhand and Bundelkhand region of Madhya Pradesh, dD studied the rich biodiversity and regional resources along with a living culture of tangible and intangible heritage that is getting lost due to ignorance, negligence and developmental plans and policies. With a team of multidisciplinary professionals, it collectively identified the assets and innovated new ways of learning and co-creation for the conservation of heritage and environment with the community and local school children as co-partners. Among many of its outcomes for dissemination was an art installation titled, ‘Dharohar’ on the tangible heritage of the region. When it was presented as part of the Disappearing Dialogues exhibition at Bikaner house, New Delhi, the public wanted to learn more about the traditionally designed drawers. They were inquisitive and expressed their wish to understand deeper, making it possible for everyone (irrespective of age, language, profession etc.) to receive, reflect and respond. The way this dissemination was played out echoed the interactive and accessible nature of archiving practised by the dD project.

The project raised questions of revaluation, recognition and restoration of knowledge and heritage by the public and the various stakeholders. From the layered multiplicity of known and unknown, it disseminated archived information and data, engaging the public as co-partners, initiating a platform of exchange, inviting the attention of policy makers and organisations that promise an impact investing in the regions. dD worked believing in its vision of not letting these discourses gradually disappear but make way for new dialogues to appear.

Unfortunately, with the thrust of globalisation we are actually erasing the multicultural textures of the world and replacing it with a uniform, standardised, schema. The disappearing nuances create disruptions, clashes and displacements – adding despair, anguish and violence from multiple stakeholders and perspectives. Those who do not conform to the standardised formats are discarded, deprived or outcast. This is a crisis of sorts, a crisis of othering and a shrinking space of dissent. However, positive change is rooted in the basic human nature of dissent, and new spaces to voice dissent, differences and conflicting ideas need to exist. The need of the hour is for collective forums and movements that are able to hold and built on dissent, realise multiple coexisting identities, value it and build on the inherent strength of this multicultural diverse group to imagine lasting, positive change.

The East Kolkata Wetlands: Biodiversity Matters

The East Kolkata Wetlands is the largest stretch of sewage-fed wetlands in the world, spreading over 12,500 hectares; an internationally renowned Ramsar site sustained by the collective practises of the peri-urban wetland community who see wastewater as a nutrient, something to be preserved as it enhances their livelihood opportunities. With this ethos, they work to meticulously use wastewater through an elaborate set of management practises to perpetuate their livelihood security. They treat the city’s sewage through fish farming, growing vegetables, paddy cultivation and animal husbandry. Thus, they perform the threefold functions of producing food, treating sewage and helping drainage along with its rich biodiversity that sustains the ecological balance of Kolkata.

Over a period of 3 years (2016 – present) dD has collaboratively engaged with EKW in a bid to foreground the immense ecological and environmental contribution of sustaining everyday life in Kolkata. Efforts have been focused on addressing the local school curriculum and working together with the school children to imagine an environmentally responsible future. Designed as a sequence of collaborative, participatory processes, the engagements explore notions of ecology, environment, everyday practice, the importance of collective action, the contribution of the community to the city, etc.

At present, development and environmental threats render this socio-spatial landscape fragile, susceptible and vulnerable. The wetlands are passing through a crisis, as is the community. The wetland ecosystem holds the key to our city’s sustainable future, but sadly, Kolkata’s citizenry has to educate itself to understand the value of this living heritage. The rampant illegal wetland filling, encroachment and development plans, poor maintenance of wastewater canals, local waste disposal into the canals, ponds and water bodies, falling production due to lack of support system is leading to growing economic crisis and rising unemployment.

The dD team of varied specialised professional artists, architects, performers, music therapist, art and nature educators, wetland researchers, conservationists and local community facilitators along with a group of young co-workers took the local issues and challenges of the region into consideration to formulate a program rooted in the environment and contextual reality. The objective was to combine pedagogy and innovation to raise awareness, and evolve modes of effective learning and build a constituency among youth for the conservation of these wetlands.

The outputs of the various workshops & initiatives culminated into various exhibitions and events, that bring to light the issues to a wider group of citizens of Kolkata. This helped scale up an awareness of urgent issues, and also create trajectories in which a wider group of concerned citizens can get involved. It also created precedents for educational institutions to assimilate certain local practices into their curricula to make the same more relevant and grounded.

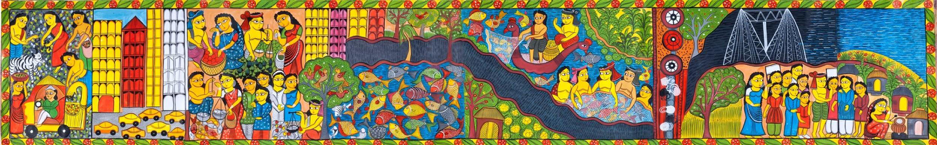

The project also developed a knowledge tool for the children of wetland schools in the form of a Bengali booklet titled, ‘Tomader Kotha’ – your environment-your stories, a calendar and an EKW diary. These teaching tools were released on World Wetlands Day, 2020 by the Environment Department, Government of West Bengal and in 2019 by the German Consulate, Kolkata. A wetland song and a patachitra also helped disseminate the EWK story and its importance. An exhibition titled – ‘A Sustainable Dialogue – engagement with youth’ at Kolkata Centre of Creativity was presented to mark the Climate Diplomacy Week on Environment and Climate Change. The main idea behind presenting the collaborators’ collective efforts was to give EKW and its community a platform and a voice to speak for themselves by showcasing a living archive of unique practises to create an exchange between the youth and people living within Kolkata and its periphery.

Creating Living Public Archives through Artistic Projects

The three collaborative projects above are examples of how we might try and change the very notion of an archive and its existence within the public domain. The re-casted form of the archive focuses on co-creation, co-production and making co-researched data accessible to all. By its very nature, the archive exists not only in the form of accessible data but is co-owned and co-authored by all the participants involved in the process. Engaging with the universal language of arts practice, these archives transcend limitations of education and linguistics and can be accessed by a wider spectrum of people in a form that is sensorial, tactile and experiential. The audience also seamlessly gets folded into the archive and are transformed into future points of dissemination – they become ambassadors of the embedded knowledge. The archive, then, is social, it is a living space of dialogue, of interaction and of growth. Such archives do not seek only to catalogue and store information but build on existing knowledge to create new trajectories for future dialogues to emerge.

Building an open forum for dialogues within India’s multicultural world folds in and foregrounds the challenges of working beyond the established siloes of creed, status, and language. The exercise helps to break out of the norms that bind us within uniformed schema to invent new multi-layered spaces of interaction, cognitive dissonance and creativity. This is the need of the hour, and together lies the possibility of co-creating lasting change.

[1] Singh, Anisha. “International Literacy Day 2019 Today; Figures On Language And Literacy In India.” NDTV.com, September 8, 2019. https://www.ndtv.com/education/international-literacy-day-2019-figures-on-language-and-literacy-in-india-2097323.