There is a lovely story of a child finding a beach filled with starfish washed ashore, picking them up and chucking them back in the ocean, as far as she can throw. An early morning walker stops her, saying, “Little girl, that’s very sweet and kind, but look, the sun is rising and in half an hour, these will bake in the sun’s rays. You have a beach full! You will never finish in time. It doesn’t matter. This is nature, let it be.” And she answers, not stopping for even a moment as she picks each one up carefully and throws it hard and far into the ocean, “It matters to this one.”

I think working with people who have impairments is like helping a star fish stuck on the beach get back home – to the sea where it is not disabled. Given the number and variety of disabilities that we see around us today, given the amount of time, the amount of personalisation that it entails, it seems as though it is all useless, if we don’t have a way to scale up. But after many years of working with people with a range of abilities, I feel more deeply, more strongly, – how well we throw – this is really what matters – not how many, not how quickly, but with what complete focus and energy I see the person. I focus on what enables and I complete my job – my throw. This is what matters. Today, when I interact with people whom I have known at various points in their life, I am always struck by what they remember, what sentence, what action, what experience they hold in their memories of our time together and what it has meant to them. I am almost always surprised by their words and I have come to realise this: no intervention is small; it often matters immensely to the person who is enabled by it.

One thing that we must remember in this context is the difference between the terms, ‘impairment’ and ‘disability’. All of us have physical and mental limitations, but because we are not thrown everyday into situations that demand thought or action beyond our ordinary capabilities, we swim along just fine accessing all that is typical in life – work, home, family, fun…. But if the physical, or social environment around you constantly demands you to do what is difficult or impossible, for these every day typical things, the impairment becomes an impediment that stops us from having a normal life, let alone achieving goals. In short, we become like the starfish on a beach. In the sea they can have their full lives, but on the sand, away from the water, without support from around them, there is little they can do. If you are on the sand, all the ability you have doesn’t matter, it doesn’t count for anything.

Let us look at the example of children with Down Syndrome. In general, in adulthood, some of their cognitive capabilities, for example, those that help them sense danger or handle complex reasoning, are like that of a younger child. But many are also trusting, compassionate, hearty and warm. Many have a great capacity to make you feel de-stressed, to console you. Most place high value on social acceptance and will do things that obtain this, without getting bored or tired. They may have physical strength though they may not have great dexterity. If they are placed in industries such as hospitality or as carers and teachers in schools for young children where love and patience and caring, good humour and enjoying being with people are valuable skills, or if they grew up in communities where repetitive hard work is how they live, they would be highly valued members. Identifying the limitations of the individual and disallowing those to become impediments on their way forward; creating environments and materials that would enable them to function as in all aspects of life available to others, are the basic things that we have to think about providing.

I became aware of disability when I was an undergraduate student at Women’s Christian College in Chennai. I was part of a slum project on health and development – it was in 1987-88 – and came across my first child with cerebral palsy. Working with this child opened my mind and helped me see how my own limitation in presenting information was the real challenge – not his impairment. And that took me to Lalita Ramanujan, the founder of Alpha to Omega, who was at that time running the organisation from her living room. With her beside me, I started to see how I could be more creative and find different pathways to bring information and love of learning to children who learn differently. Later, I moved to Mumbai to join SNDT University to study Special Education. My life took a real turn after I attended a lecture by Beroz Vacha, the founder of Helen Keller Institute for Deaf and Deafblind (HKIDB) at Byculla. She was running the school within a government school at Byculla. I was amazed and fascinated by this world she was describing. At the end of the lecture, we met, and she asked me to volunteer at the centre – work in the school, live in the hostel with the children, eat there, live there, and spend time my evenings with the children. I had no experience in dealing with the deadblind, and was fascinated but hesitant. She was an incredible and very perceptive lady – she could persuade anyone to do anything.

I went to work with Beroz at the institute, which was the only one of its kind in India. I soon discovered that working with the deafblind was endless learning for myself. You have to reimagine every concept for people who have not seen or heard anything at all. You will have to find ways to teach them words they will never hear, describe things that they will never see. Some children started with one impairment and developed another, but retained hazy memories; others were born with both. Some had a little of vision or hearing; some others, both. You had to really get inside their experience of situations, of life, of events to be able to give them the right words or help them form the right ideas. It was a life-changing experience – it shook me out of all my preconceptions about learning.

I stayed with the children; I was also their hostel in-charge and quickly became mother or aunt/ elder sister in addition to teacher. I listened to their teenage fury and confusion, I sat with them through illnesses and counselled them through scrapes, physical and emotional. I never quite slept at night, half my mind was always awake to notice the rhythm changes in the breathing of the children around me. I interacted quite easily with each child as their teacher. I sat in planning meetings, feeling like family, my hackles rising with any imagined slur on “my” kids. My time at HKIDB, and the many discussions and arguments with Beroz, moulded me into the thinker and teacher that I am today. Now, every time I work with a child, a family or mentor a teacher, I draw from the lessons from those days.

Beroz had been asked to help to start a centre for deafblind children in Delhi, and wanted someone to take charge of that. She thought I was the one to do it; and offered me a chance to go to the USA to study and come back and start the centre. But, I did not see any sense in doing this, given that I was already learning at the feet of someone who started a programme for the deafblind in India. So, under her tutelage, I worked with the students and studied with her every Thursday evening at her home. I started home-based services in Delhi in 1992 and then moved there full time in 1993. In Delhi, I developed services for the National Association for the Blind, and also travelled to serve children and families in the rural areas of Rajasthan and Haryana.

Working with the deafblind makes you inventive and sensitive as a teacher. The primary tool you have is hand – it must serve both as the way in which you talk (sign) with the child, and as the way in which the child gets information from objects. Everything must happen in a sequence – unlike the child with vision and hearing, you can’t show them something and talk at the same time! Features about objects themselves are obtained in sequence or little chunks of information – temperature, texture, shape, size – to obtain each of these things, you need to use your hands differently. You must also teach them to ‘read’ touch, and comprehend complex ideas like irony, surprise and imagination. One advantage – or is it dis-advantage? – of this is, the learners often become very sensitive to information received through touch. You can’t easily pretend before them. If you have sight, I would know how to cover my emotions from you. When we hold our emotions within ourselves, we are not aware of our bodies, the small tensions and ways of movement that give away our real emotion. But my students knew; from my sign, from resting their hand on me; they could tell so quickly and clearly, often seeing my emotion even before I was fully conscious of it. I found it exhausting to deal with such exposure, but in the end, I think it made me more truthful to myself and therefore, to others.

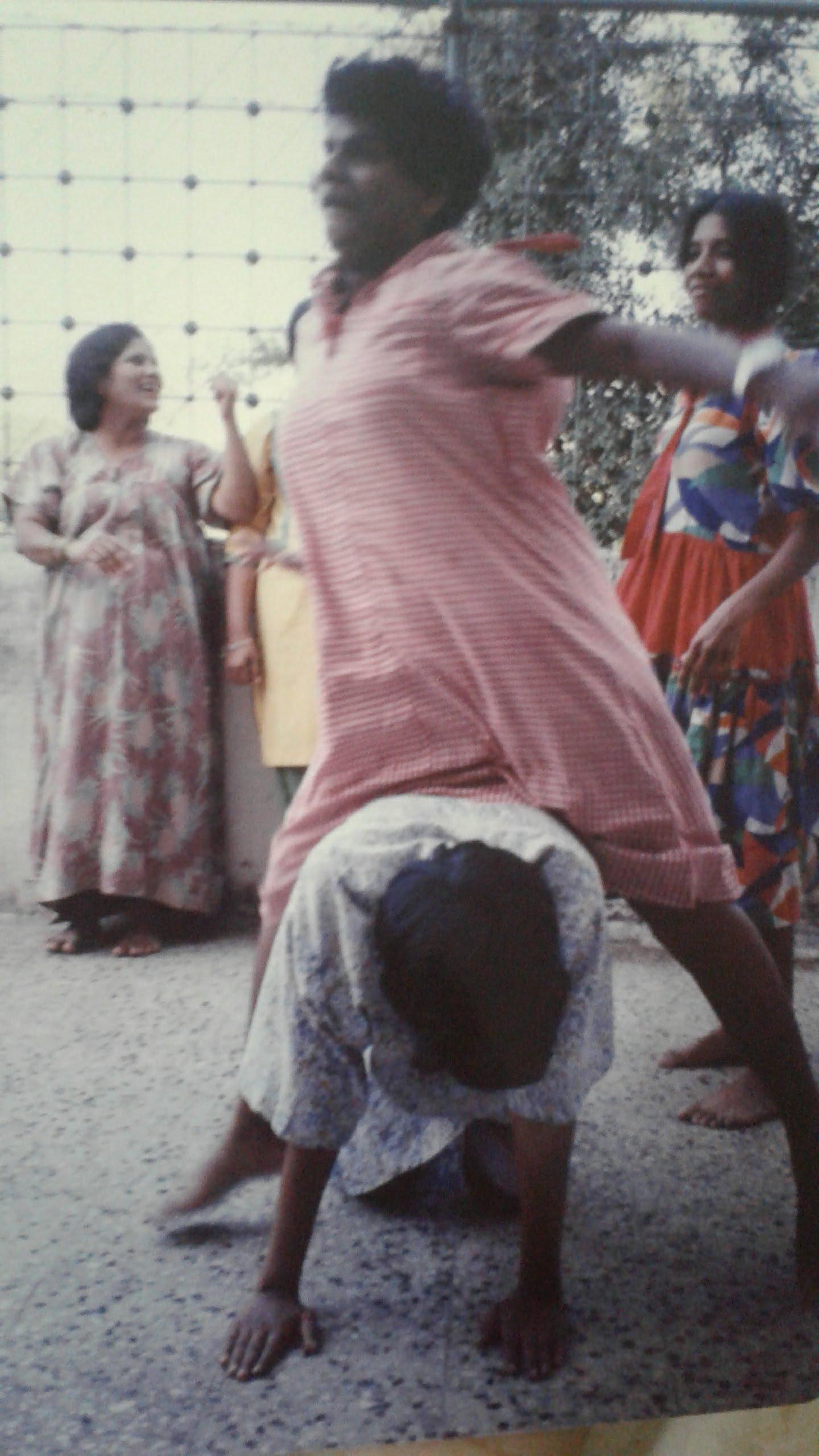

There is a general conception that anger is a bad emotion, but I feel more hopeful when I see anger in learners with impairments, because the energy of their anger is as useful as their curiosity to me. It means they can be touched emotionally; I can work with it, channel it into creative ways. In a class, you slowly develop an alternative linguistic experience – you have your jokes, silliness, gestures, victories, trips and flips. Sometimes, you see intelligence, but you do not know how to approach it, deal with it, use it.

‘Intelligence’ is a word that must be understood very deeply. We are so used to interpreting the term in a linear manner, we do not even appreciate intelligences outside the verbally articulated mental type. But with kids who are deafblind or have complex learning needs, seeing and connecting with the child’s native intelligence will make you feel like a Lord of Language. When you begin, their active experiential world is rather empty outside of ‘touch’ which in itself they cannot quite process as yet, and you think – how will I begin to fill it, expand it, instil emotionality into it? This is where you begin to see ‘other’ intelligences, such as the ability to nurture, to provide, to care, to celebrate. Some of the deafblind children can smell unhappiness or trouble, and you see it. One of my students whose motor functions were profoundly affected, too, had this ability. He was like a noodle, literally – could not even hold you, but his intelligence about my unhappiness would make him respond in a way where his touch would just flow on me. I saw his attempt – how would I tell him I appreciate it? How would I imagine an intervention that will make his world richer, broader, deeper?

When you see someone like that, you try multiple things. We can’t just imagine physiotherapy will help, because it is not just a motor system, but a whole child who feels everything – pleasure, interest, fear, rejection, defensiveness, boredom. It is at such a point, when you see the potential and it aches to see it shut in, you jump in and do things which often seem silly to everyone around you. And you accept everything, welcome even the anger of the child as a useful tool to enter and join their experience of the world.

There is an enormous lack of awareness among general public about all that can change. Viewed from the experience of the person and not the existence of impairment, life can be rich and valuable and glorious. Ability and impairment are equally ignored and people tend to see things in little blocks. For instance, a person with cerebral palsy can have serious visual impairment. But parents and professionals tend to see it as a package, and see the most visible issue – cerebral palsy – as the cause and effect of all other problems. They don’t realise the need to search for and deal with each issue individually towards enabling the person’s access to fuller experiences.

While in Delhi, I used to go to the villages of Rajasthan. It was an experience so different from what I had in Chennai and Tamil Nadu where I felt there is more public awareness about the possible interventions. I realised that till today, rural or urban, many people are not even aware that there is help available. In many homes, still these things are not even discussed. They provide care, but love is not enough to release a life, to learn, to live, to chase a dream. The government has to address this question of communication and outreach.

In a country like India, the gaps in understanding are quite big. Very often we see that the public space is wired only for ‘the normal human’ whose verbal abilities are almost taken for granted. In this majoritarian situation, all types of minorities and their languages are marginalised. The government and other agencies must put their effort in an effective advocacy for a democracy of languages. If we do not take care of this, and continue to make sections of our population feel disabled by the language choices and limits we place on them, all our demographic dividend will come to nought. Again, such attitude is corollary to the anthropocentric attitude that drives many of the contemporary development schemes, which makes them rather insensitive to the needs of not only the minority humans but also the rest of the creatures on earth. Even though human beings form only a very small portion of the larger living world, a blatant exhibition of human power constructs a majoritarian narrative. The same way, if we continue with our discrimination of people with disabilities we will make a future that is very uneven and frankly quite boring. My own experiencing of the world has become richer by seeing it with my students.

In retrospect, I am really happy that I did not go to the USA when Beroz proposed it, and, instead, got involved in work in different parts of India. Otherwise, I would have come back with a different set of ideas and theories bred in a space where facilities and knowledge parameters are different. I could not have imposed any external idea on any of my students in India; I had to work with them, and learn it on the job. Reflect on their reality and my limitation. I had to know them from my own experience, my own knowledge, my own failures, my own discoveries.

It was only some years later that I felt prepared to compare notes with the West. So, I got a scholarship and got to study and work there for some years and then went on to Berkeley and got my PhD, doing qualitative and quantitative research set in Tamil Nadu. Back in India, I set up Chetana, my volunteer-run organisation in March 2004 to make enabling educational tools. Today, many of my students work with me as colleagues and advisors. Volunteers – friends and old students, from across the world share their time and expertise.

Chetana’s thrust areas are access to education and health. We focus on achieving this through action-based research. We work to define problems, develop protocols to clarify the issues, develop and test strategies and use the process of assessment itself to begin to create solutions. While we are testing we are already developing protocols, creating learning material, building trainer capacity, making policy guidelines for schools, offer guidance to schools and hospitals etc. For example, when we realised that vision was not well supported in children with other disabilities, we started documenting several aspects – social, caregiving, problem identification, aetiology, clinical and rehabilitation services and findings. From this “I Count” registry, we started identifying areas that needed intervention and after the first 100 children were assessed, we were already creating partners and networks of service. We have published our data and over the ten years of the project can say proudly that we have enriched and changed for the better the services in this city. Today we support students in optometry, rehabilitation and even engineering to do studies and projects in various aspects of this area. There is so much of awareness about the need for proper assessment and both clinical and rehabilitation intervention now – this has been a very impactful project.

While we are speaking of awareness and language, it is normally advised that we use politically correct language while talking about disabilities. I feel, mechanically using terms like ‘specially abled and differently abled’ does not help. When one uses such euphemisms, it gives an appearance that the people who are thus referred to have some special abilities. The truth is, despite the way they are addressed, they indeed ‘feel’ and ‘experience’ the limitations placed on them by the society, by physical and attitudinal barriers. And, it can be felt more as a patronising gesture that takes the focus away from the disabilities that actually need help and support in so many ways. These days, the term ‘people-first’ is used to promote the idea that someone’s disability is not the defining characteristic of the entire individual. For instance, you say ‘the girl who is blind’ instead of ‘the blind girl’ by allowing the girl to be the focus and not blindness. That language should find its translations in an open attitude and larger public action. Chetana, through its work, attempts to achieve this goal, too.

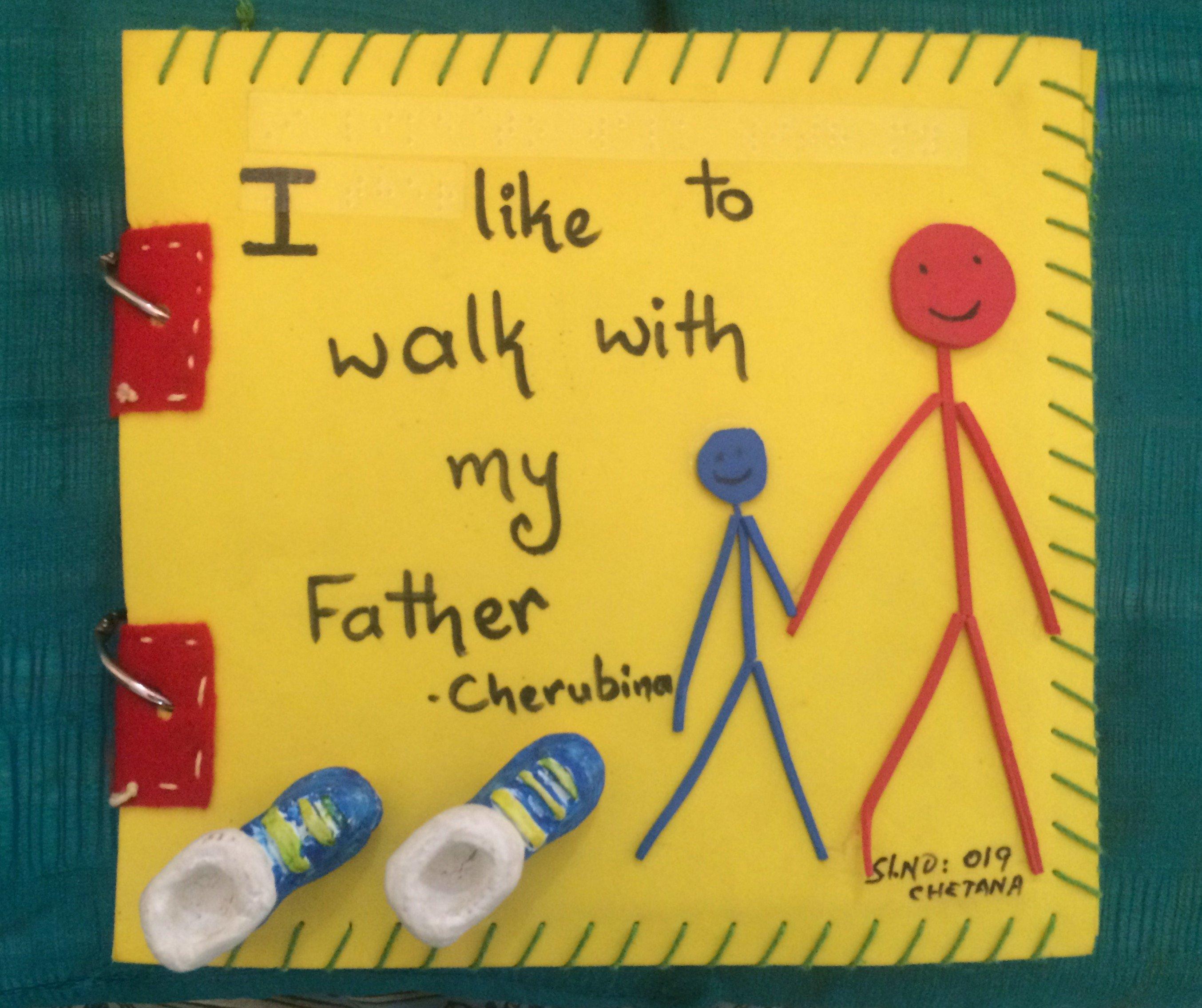

Our latest flagship project is literacy and language. Through the I Count, we came across and followed children across areas of impairment, ages, varied access to rehabilitation and education, and one thing stood out – far too few achieved literacy! Was it the hours of therapy? Was it the lack of importance? Reading, if achieved, was rarely fun, and stories if at all, were listened to, rarely read. A little research and it became evident that they never had those early story books – for many, the first book was a text book. For many more, they had never actually held a book at all. Perhaps because of my experience with the deafblind – I believe that adding textures to images, adding interaction to books is an excellent strategy to make books intriguing… to invite the uninitiated, to hold attention, pique curiosity… and so it began. We starting dreaming up books, finding volunteers in the most unlikely and interesting of places – engineers, grandmothers, college students and of course, writers… Slowly ides, creations, inventions grew – machines were built, stories were churned out, and from across the country, different hearts, creative minds and nimble hands started constructing books for us.

As with the I Count project, the act of creation is also one of raising awareness, of education, of enriching lives and learning. Final projects, inventions, story books and all kinds of small research projects have tumbled out from this work of ours. We had to pick a focus – the children or the teachers or the parents… We decided that the most important thing to do today is to focus on the kids who haven’t quite begun, the ones who have access to instruction, but who are not succeeding. The ones for whom reading is a pain and no fun at all. The ones who can painfully read a story, but it doesn’t lead them to dream and imagine and fly beyond the book – as any good book should do. There are many such children who have impairment that make accessing literacy challenging and if we were better as educators and families and publishers, there would be fewer for whom reading became an area of disability.

Building books takes time. So, this means that if we make 5 books a month, we are ecstatic. In 2 years, we have reached about 300 books. I think Chetana achieves meaningful scale by doing two things – we set ourselves up as a library, so that our books go out every month – the deeply thought through and painstakingly adapted My Mother’s Sari or The Giving Tree, is read by numerous children, not just possessed by one. Discussing with friends and parents and teachers, and choosing a wish list, and then receiving a book, the discussions about the books with us and with one another, the special status of being an Accessible Reading Materials library child with a cool badge and a bag filled with surprising and interesting books, give them an excitement to read the story books. In our follow-up visits and discussions, we see that children and often entire families are really engaged.

The second thing is that we develop a community of people and of knowledge of book construction. Rather than trying to increase our reach and stock, we share our work freely with anyone who wants and encourage them to build a library like ours. We work with teachers, artists, engineers and artisans with various skills to develop problem solving techniques and we are quite excited about the potential of some of our techniques to work in professionally mass-produced books. But we know that the mass-produced books are only effective for certain kinds of stories and mostly for those who already have at least the foundations of literacy in place. For the richest range of books, handmade creations are unbeatable. Our best and most loved books are handmade.

Most people when they come to talk about our work, bring the conversation to the question – how will you scale up. Isn’t everything really actually meaningless unless you can scale up? I answer that like the girl who gets the starfish into the ocean, I work with small numbers. I concentrate really hard on what I am doing and do it with all the force of my heart, my energy and bring to bear all the experience that my rich life has given me. I value life enough that 1 is as fantastic a victory as 100 or 1000 or even a lakh. I will always remember that it took one teacher – Anne Sullivan, her entire lifetime to work with one student – Helen Keller – which brought unimaginable hope, language and a chance for change to many generations of people with disabilities around the world.

Our Aditi switch design was created for one student to access her computer and look where it took her! A college graduate, a business woman and today a member of my Professional Advisory Committee, Bhavna Botta is an example of how removing one block can let a river flow free. Actually – that’s not true – with her energy, with or without Aditi, she would have been what she is – fantastic, spirited and spectacularly independent. But that’s what we do – find a block and remove it so a life flows more smoothly. Sometimes the blocks are little ones, and sometimes, the block is a main door that needs to be unlocked. Then they are unstoppable because you took the time to address the problem and see it through. That is the thought and philosophy that guides everything we do at Chetana – be it the vision project, the assistive tech project or the library. We count. One person counts; because everyONE matters.

Written by Rizio based on an extended conversation with Namita Jacob.