The Rafoogar’s Yarns Crossing Time. [1]

Human life is an intimate reflection of the perennial cycles of nature. All existence on earth depends upon the regular arrival, change and departure of the seasons, a manifestation of reet, the cosmic order. It is all one process, one energy. Opposites contain each other – expansion and contraction, dispersion and concentration, reduction and augmentation, occlusion and clarification, emanation and dissolution. Darkness veils light; light infiltrates darkness; through increasingly refined gradations of luminosity the gross becomes subtle, opacity becomes transparency; original states cycle through reincarnations, and the reiterations and revisions continue…

A deeper understanding of these processes of Time has come to me from my intensive long-term research into rafoogari, the traditional art of specialized ‘invisible’ darning, as well as from my working closely with the rafoogar community. I have drawn upon and applied those deeper realizations about the many invisible reclamations of the body of the cloth across time in the domain of my work as well as my daily existence. My research documented the skills and sociology of the rafoogars, but also enabled me to see darning as a powerful metaphor – to understand ‘repair’ as a healing modality of intimate self-knowledge, and to honor the place, significance and act of visible and invisible ‘darning’ in the fabric of any life, as well as in the life of any fabric that erodes over time. The edges of gashes and fissures in the vulnerable weave are continuously identified and aligned by the darner, firmly yet delicately positioned and pinioned, and then sealed stitch by mindful stitch, to prevent further ripping and other damage and to render the injured cloth intact and whole.

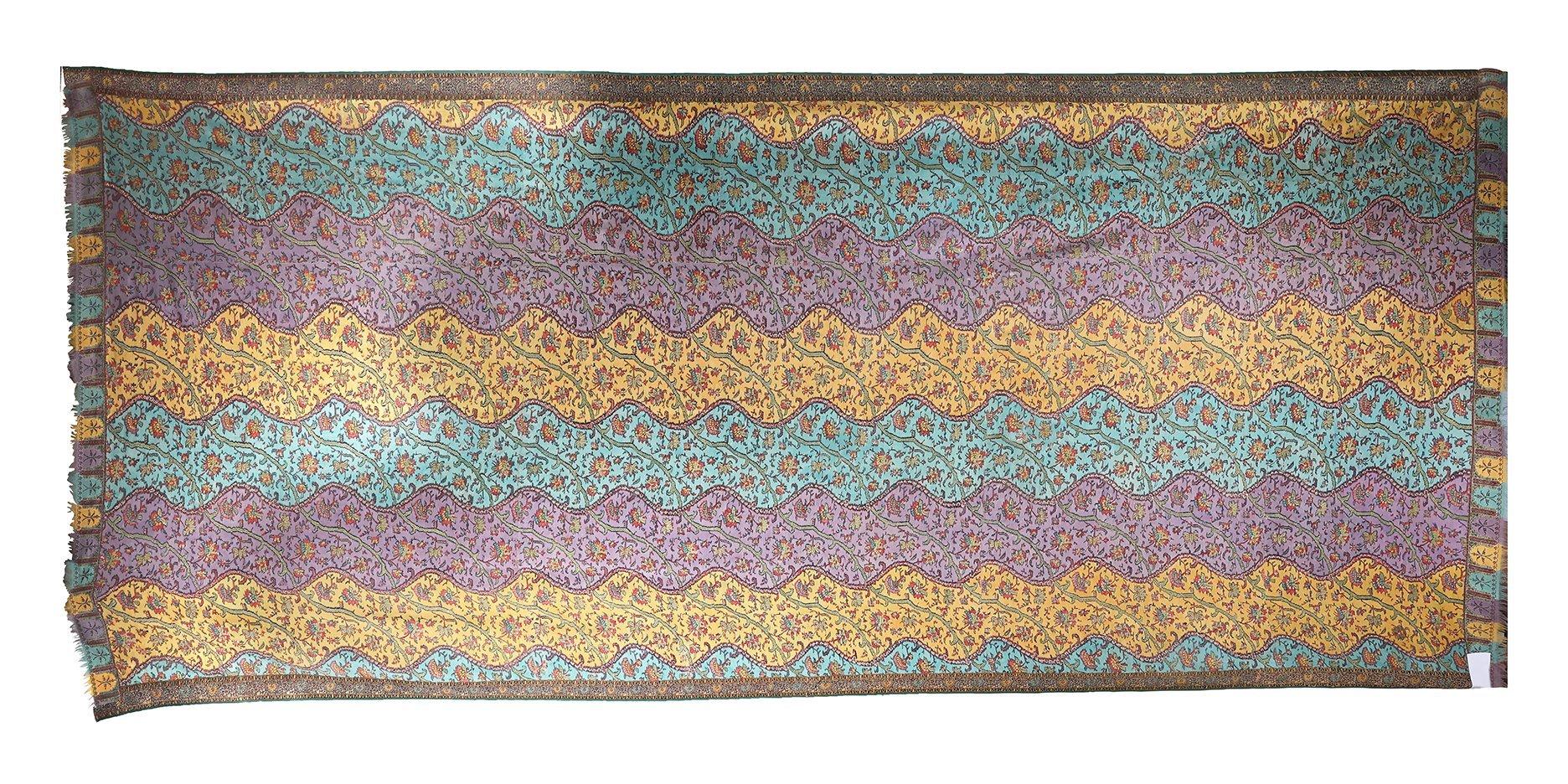

Rafoogari has existed everywhere in India for centuries. Yet not many would know the crucial role of rafoogars in the creation, maintenance and renewal of celebrated clothing styles. A case in point is the antique kani (loom-woven) and amli (embroidered) pashmina shawls of Kashmir. Rafoogars renowned for their unique hereditary techniques of ‘invisible’ darning have always been integral to the creation of Kashmir shawls, from the core processes of weave-repair, joinery and decoration to the mending and preservation of pashmina items damaged after use.

The weaving methods of these elaborately designed and meticulously produced fabrics came to the north-western subcontinent from Western and Central Asia along with Islam. Assimilated into indigenous craft practices and genealogies, these weaving techniques became further refined as centuries of deep social acculturation and aesthetic symbiosis took the weavers’ knowledge, creativity and finesse to further limits. With changes in usage, patronage and customer demographics, shawl formats underwent transformation: the original men’s shawl of the Mughal period is converted into smaller women’s shawls; a square rumal is recomposed into a rectangle, etc. Exquisite imperceptible rafoo is applied to every sort of wear and tear; the structure of the ripped or eroded weave is meticulously rebuilt with the needle; seams are opened, realigned and re-sewn; salvaged borders and pallas are attached to plain or embroidered fields to create a ‘new’ shawl; tukris (leftover discarded pieces) are miraculously sutured into a fresh entity, infusing new life into a dead cloth. And mirroring this celebrated invisible architecture of the kani shawls, a modality quite opposite to the celebrated glorious needlework of the amli shawls, the community of menders itself remained unseen, never bestowed with the same status as other underprivileged artisans in the long and complex history of Indian or world textile traditions.

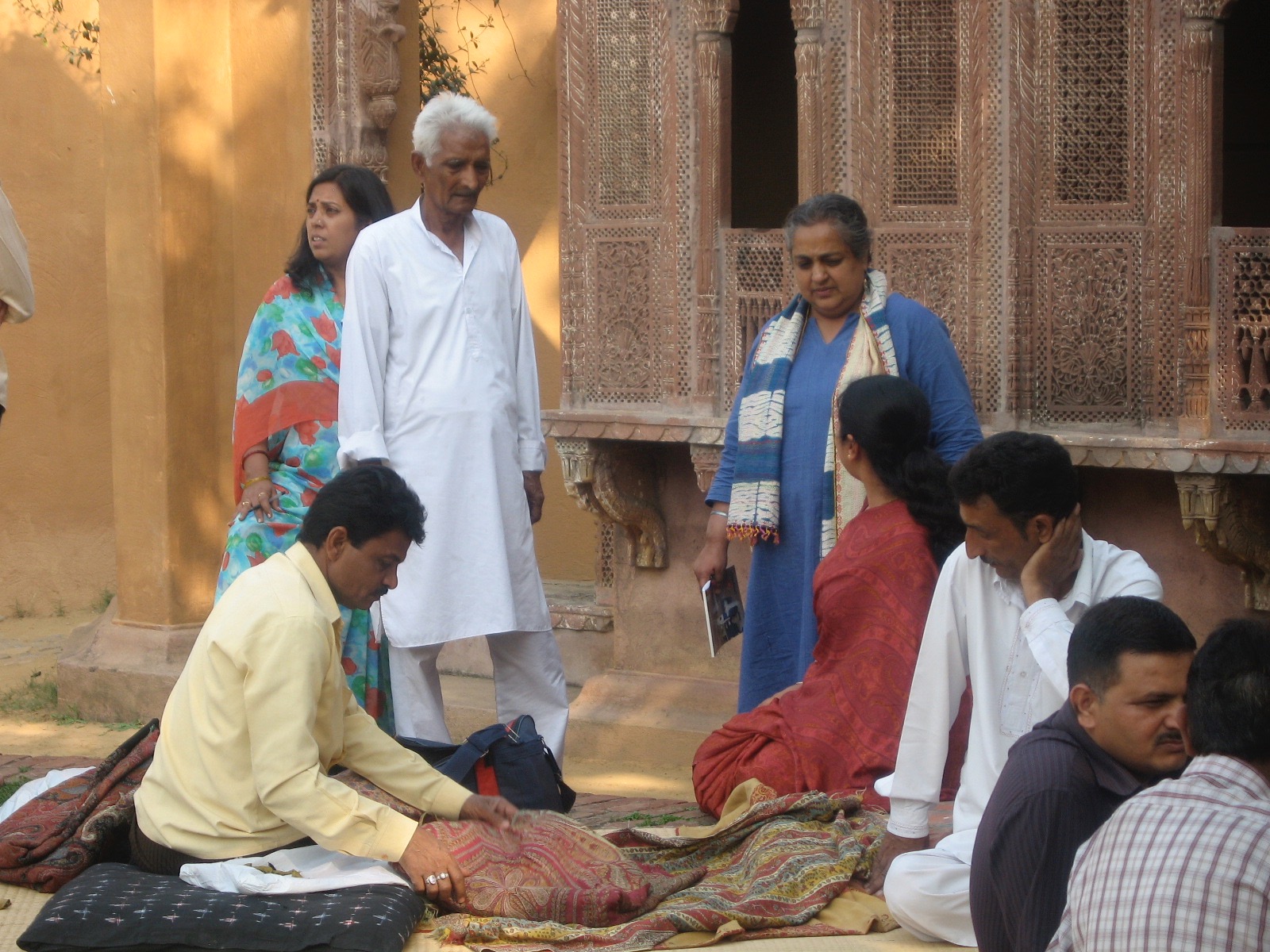

I first discovered rafoogari through my personal and family connections with Najibabad, my hometown. It has its own resident rafoogars, and the cross-country routes of itinerant rafoogars pass through it. This network earlier radiated from Kashmir. It is more dispersed now, and the paths, though less travelled, still intersect with the old trade and exchange hubs that accreted around local darbars, havelis and cloth markets. Rafoogars tend to cluster in older townships where master-craftsmen are still commissioned to conserve ancestral heirlooms or other precious acquisitions. These interactions take the form of annual baithaks or ‘sittings’ in the comfortable space of the client’s own home, relaxed, informal, but focused on the work. The rafoogar is consulted; he advises. Discussions may ensue. News is exchanged and time-honoured family bonds renewed. The master-darner distributes the mending to be done, and he and his assistants commence working through the day.

It is truly ironic that the skilled artisans who still specialize in darning and embroidery so fine as to be considered ‘invisible’ have, with the passage of time and exponential changes in textile technology, consistently remained practically invisible themselves. Being resilient, versatile and innovative, rafoogars have carefully protected the ‘secret’ knowledge of their hereditary craft that is still passed from generation to generation within the community, and survived by doing the simplest possible piecework and mending in bazaars. And this is how most of us perceive them. Yet today’s master-rafoogars still command an astonishing precision – within micro-millimetres – with the needle in relation to repair of any kind of fabric. Just as significant as the rafoogars’ virtuosity with the needle is their intuitive diagnosis of textile damage, and their deep knowledge of restoration methodology that enables them to work with equal ease on delicate 18th-century kani pashmina shawls, on fine high-count jamdani muslin, on ceremonial antique garments such as elaborate jamas and angarkhas; and equally, on traditional decorative floor-coverings of wool, silk and cotton.

If in the past an antique pashmina shawl acquired its status through the perfection of its patterning, its intricate weave and the excellence of the invisible rafoogari integral to shawl production, today these historical textiles retain their original value via flawless repair and transformation at the hands of the darners. Rafoogari is indeed an expression of fidelity to the original design template, but as a living tradition it is non-mimetic – rather, it is inevitably and simultaneously a recursion, diffraction and fusion of techniques and trajectories. The old shawls undergo dynamic reincarnations, ultimately becoming subtle hybrids rather than replicas. But whatever the form of the shawl, and regardless of whether it is a personal possession destined to pass through the hands of different owners over time and changing circumstances, or whether it is classified as state property, locked behind glass in a museum or other cultural institution, these textiles have always been nurtured and preserved solely by the vision and the nurturing hand of the anonymous rafoogar. The act of mending such shawls, therefore, becomes more than just reconnecting and replacing and reconfiguring the threads – it is also the stitching of one life to another, one era to another, one context to another, one cultural idiom to another, as the old shawls, made ‘new’ through invisible rafoo, pass into and out of the hands of fresh sets of owners. Thus, rafoo may also be understood as a modality of duration, a unique invisible ‘joining’ of past and present, a felt paradox – the past concretely embodied in exquisitely repaired heirloom textiles that seduce the eye, while in the present the unseen artisanal effort, labour and talent underlying this achievement remain an abstraction.

Priya (in blue, picture on the right) with rafoogars at a workshop at Sanskriti Kendra, Delhi

We mostly forget that the act of darning is far more than a surface application – it is in fact a fundamental reconstitution of the weave itself. The rafoogar/needleworker, considered in general terms to be an embroiderer, tailor or seamster, can in fact be said to function as a co-creator/master weaver, recreating and replicating complex traditional patterns with remarkable ease, confidence and patience. However, the urgent question confronting us today is not about the revival of this craft, but about the survival of the craftsmen and the continuity of the rafoogars’ invaluable, irreplaceable indigenous knowledge. With regard to Kashmir shawls, are we more concerned with the preservation of these extraordinary objects, or with the preservation of the extraordinary skills that make possible the preservation of these extraordinary objects? These skills can only be preserved if we ensure the preservation of these exceptional darners who have so far largely remained as invisible as their incomparable darning – a community so adept, yet so intangible, elusive, silent, absent from India’s heritage and textile discourses, a gap in the socio-cultural and historical record. Do the imperatives of preservation mandate that in order to concretely benefit this neglected group, we impose the very opposite of their situation – i.e., bring the rafoogars and their tradition into public view?

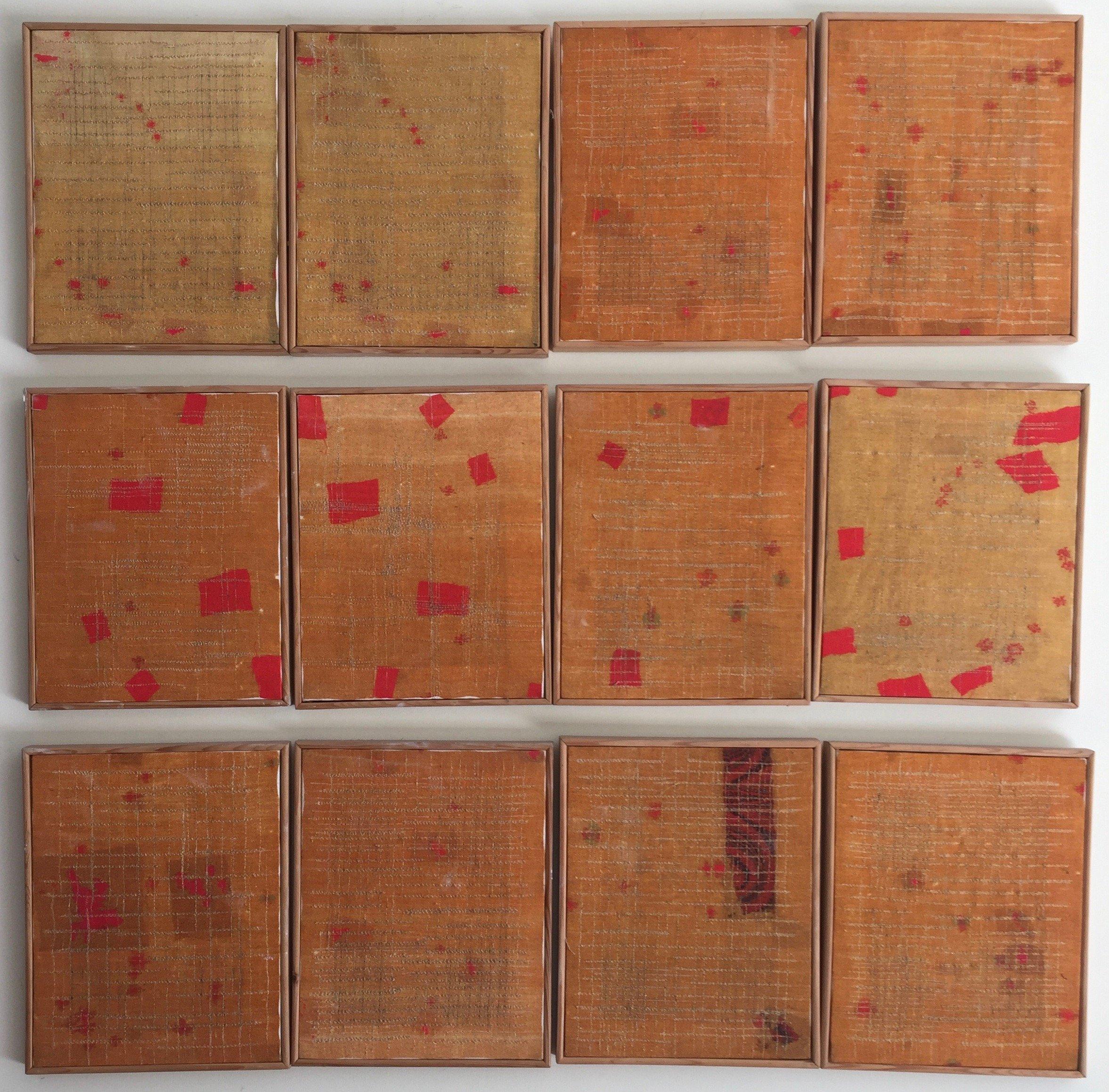

Over time my textile art practice began drawing more and more upon principles of rafoogari as a core referent and aesthetic instrument, an innovative way to create new art in our contemporary context. And when I consider rafoogari in a register other than the existential, I am reminded that Sruti defines the work of the Vedic seers and poets as a description of the constitution and reconstitution of the metaphysical weave of non-duality: timeless transcendence expressed through our cosmos and experienced as the powerful flux and interdependence of organic life, ever manifesting and mutating, incessantly adapting. Through my rafoo-themed works I have symbolized the journey of any time-bound being as a stitched/‘darned’ collage of interstitial, transient, recalcitrant, liminal interfaces – material warp and weft always subject to visible and invisible trauma, always evolving, and always a reminder to accept and adjust to whatever offers itself for manipulation and modification.

My thematic focus here is on impermanence, rupture, abrasion, attrition, friction, corrosion, and the internal relationships of these processes. Equally, it reflects my belief that anything injured, harmed, disfigured, demeaned and degraded has the potential to be recuperated, conserved and cherished, and to be continually bestowed with fresh value, energy and utility. The methodology of ‘darning’ has come to represent an irreversible, intuitive merging of my artistic and personal paths, a fusion that finds expression through artwork that incorporates rafoo. Earlier, my ‘life’ and my ‘work’ were flowing in parallel, but now they seem to have undergone a mutual transposition and beyond – their boundaries have merged, they seem to have been woven into one.

Priya’s earlier engagement on Inter-Actions was titled “Inter-Actions”, once again reminding us how deeply she had known LILA:

Edited by Smriti Vohra

Images: Monica Dawar and Priya’s Archives

[1]Parts of this article appeared in Priya’s text panels and other writings associated with her exhibitions and research