LILA: Thank you for participating in this issue of INTER-ACTIONS, themed PUBLIC. We would like to begin this conversation by understanding the core philosophy of Janam. What is the driving vision that brings all of you together?

Sudhanva Deshpande: Janam was formed in March 1973 by a group of youngsters who were earlier associated with the Indian People’s Theatre Association. The story of that falling out needn’t detain us here – Safdar Hashmi, one of the founders of Janam, spoke about it in an interview he gave to the theatre scholar Eugene Van Erven in 1988, about six months before Safdar’s murder, and more recently I have recounted it at some length in my book, Halla Bol: The Death and Life of Safdar Hashmi (LeftWord, 2020). The important point is that Janam in a sense came out of IPTA and has carried forward the same legacy of theatre that is committed to the ideals of equality, secularism, and anti-imperialism. It is a theatre committed to the ideals of social, economic, and gender equality. ‘People’s theatre stars the people’, was the slogan of IPTA, and Janam has adopted the same slogan, because it puts the lives of the vast majority of working people at the centre of its creativity.

LILA: Having started as an experiment in the forms of theatre, how do you think Janam has evolved over the years, while capturing the resonance of thousands of raw voices?

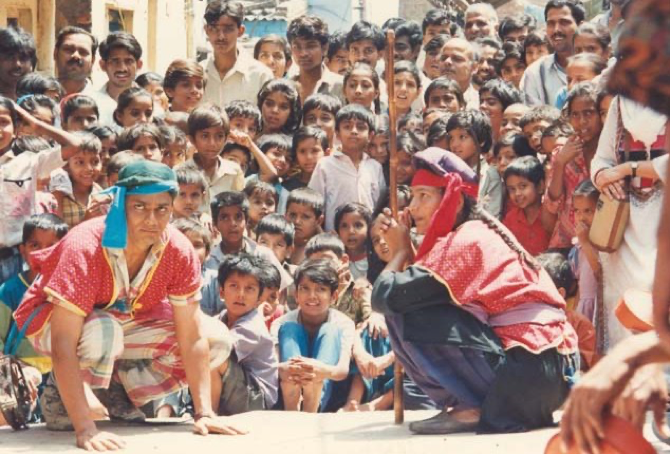

SD: We didn’t start out wanting to experiment with form. We wanted to take our theatre to the people, to not remain confined to bourgeois playhouses. Of course, we also played in established theatres if and when we got the chance, but we didn’t set ourselves up for that reason. We always wanted our plays to be performed in front of working people – women and men who work in factories; in a range of more or less precarious jobs in the informal sector; in the fields, orchards, and plantations; as well as white collar employees. Initially, we only did stage plays that were mounted on make-shift platforms, and played to mass audiences, sometimes numbering thousands. After the Emergency, though, this became increasingly difficult, because the organisations that invited us to perform – trade unions, the Kisan Sabha – were now impoverished, having been underground for so long. They said to us: We need your plays, but we cannot afford them. So we decided to create plays that anyone could afford. Plays that were inexpensive to mount, flexible to perform, and politically sharp. What resulted was street theatre. It’s not like we went out looking for street theatre, or that we were trying to replicate something that had been done elsewhere. Our street theatre was a direct result of the political circumstances we found ourselves in, which had grave financial implications for our existence.

Having found street theatre, we realised immediately that it was a powerful form. So we began exploring how much we could push it. But these experiments, if you can call them that, also came out of another realisation. You see, we learnt very soon that when reality changes, you need new vocabulary to speak about the new reality. So the impulse was not artistic per se, it was political.

But I should also say that as a group, right from the outset, from the early 1970s, we’ve been deeply interested in questions of form and the artistic process. We’ve held that the people – our audiences, ordinary folk oppressed and marginalised by the ruling classes – deserve the best art, just as they deserve the best politics. To put in differently, the best politics in the world is useless if it is presented in sterile, artless presentations. For political art to be meaningful, for it to have deep and lasting impact, it has to be both – good politics, and good art.

LILA: You have performed street theatre in some of the most violent times in Indian socio-political history. What would you say about the evolution of the ‘public’ as viewers? Have you experienced any rapid or gradual transition in the ways people interact with a performance and its content?

SD: One of the big changes, of course, is the ubiquity of the mobile phone. Not only does it mean that people, especially while watching street theatre, think nothing of having a conversation on the side as the performance goes on, it has also meant something we don’t often fully consider, because we are very much part of it. That is, the inability to take in an experience fully without immediately first whipping out one’s phone and taking pictures or making videos of it. In an auditorium, audiences are constrained by the etiquette or rules of the space, but on the streets, neither exists. I find it amusing that people look at the play happening live in front of them through their tiny screens. Why would you want to reduce the size of the image thus? But there is a great anxiety of missing out – FOMO is real, and not just limited to aspirational millennials. It is almost as if it isn’t on your phone – and, therefore, on social media – it didn’t happen. This might be a civilisational phenomenon that the human race will have to contend with.

More specifically though, you’re more likely to be accosted by someone who accuses you of being ‘biased’ if you do a play on communalism today, than, say, 30 years ago. But even in the present time, we’ve continued to perform – as much as 200 to 250 shows per year – and often said things that are uncomfortable for the Hindutva brigade, without being physically assaulted. I don’t want to make this into a promise, because one is sometimes just that one little step away from being attacked, but so far, we have managed to continue to perform without having broken limbs! But the propaganda of the Hindutva brigade is relentless, the poison they inject into society continuous and in ever increasing dosage, so that is one of the major challenges one has to confront. Personally, I believe we have to be careful, not reckless, and we have to find clever strategies, both creative and organisational, to be able to keep performing.

LILA: You also perform in front of a variety of audiences across the country. Can you tell us a little about how similar or different these experiences are? Do you ever feel the need to modify your presentation based on the social, political, educational or cultural background of your audiences?

SD: Well, we actually don’t perform so much all over the country. I mean, we have performed in many places, but we aren’t a touring group really. We are all working people, or students, or looking for jobs. Travelling means taking leave from work or studies, and that is often difficult. We are very much Delhi-based and Delhi-centric. The audience we have in mind when we create our plays is the audience we know most intimately, from the bastis and industrial areas of Delhi. It’s funny how if we are able to make something that works for our core audience in Delhi, it tends to work all over the country. Except maybe in rural areas, where the rhythm and pace they expect from a performance is different from what we offer. They can’t understand why a play should be over in less than 25 or 30 minutes! That said, when we do travel, we try and bring in local references, especially jokes that a local audience would understand and appreciate. People know you’re outsiders, and they appreciate the unexpectedness of a local joke.

LILA: How do you decide the scope of a public space in your performance, and how do you communicate through it – how much of it can you actually use and what would be your language(s)?

SD: I’m not sure I understand your question. So let me talk about something you haven’t asked about, but I think is critical – the shrinking public space in Indian cities. Take the example of Delhi. There was a time you could perform pretty much anywhere in the city without too much trouble. We used to perform quite regularly in the Central Park of Connaught Place, or at the Boat Club lawns where, especially in the winter, one finds thousands of government employees lounging about. Or, if you knew someone who stayed there, you could go into any middle-class locality or housing society. Working class neighbourhoods were not a problem in any case. In all these places, you could perform quite openly, and if the police did turn up, you could, in most instances, get away by sweet talking them into believing in your harmlessness. Today, forget about performing in central Delhi, which is under perpetual Section 144. That the State would become more and more intolerant of alternative viewpoints, particularly in the neoliberal era, is to be expected. But what I find even more alarming, in a sense, is the tendency of the rich, and therefore of the middle class, to pretend that they don’t belong to this nation. They want to seal themselves off in their gated communities with their security protocols, they want to live in a bubble surrounded by artificial landscape, breathing artificial air, eating artificial food. It is as if the rich have seceded from this planet. If you look at planners’ layouts of the so-called integrated smart townships, you’ll find they account for multiplexes and malls, gyms and restaurants, golf courses and running paths, but not for live performance spaces, indoor or outdoor. The spontaneity and life of an India street or mohalla is despairingly absent. They want to euthanize the culture of the Indian public spaces.

LILA: The ‘smart’ gadget-oriented design of urban India has led to an increasing sense of loneliness and lack of intense social interactions, even as it has made communication more convenient than ever. How do you view this dual effect – on the one hand, spreading the word of resistance in larger spaces, while on the other, taking away the intense interactive experience a street theatre performance otherwise provides?

SD: I’m responding to your questions at a time of the Covid-19 lockdown – so the question takes on a whole new dimension! But even after the lockdown is over, and after we limp back to something resembling ‘normalcy’, the wider import of what you say remains. Today, everything is supposed to be ‘smart’ – your phone, of course, but also the other gadgets in your home or office, your car or other means of transportation, your entertainment, and in fact even the city you live in. Now, what is ‘smart’? I’m not an urban planner or technologist, but it appears to me that what is meant by ‘smart’ is something that is expected to be able to anticipate and provide for your needs even before you articulate them – lights that turn on in rooms before you enter, cars that already know where you need to travel and the best route to reach you there, delivery services that know what you need to buy, medical services that know you are unwell before you realise it, personalised apps that know who your friends are or should be. It seems to me that all this is designed to make the human race not smarter, but dumber! So there is no question in my mind that live performance will acquire a renewed force and vigour in the time ahead. People will crave for human contact, for collective experiences that break the atomised, solitary experience of having been turned into a data point by a giant capitalist algorithm.

There’s also another dimension to this. You see, democracy is not just about holding elections and forming governments. Democracy is also a culture, a habit, a way of life – where you learn to listen to other views, appreciate them, where you hear the small and weak voice and respond to it, because respecting and enabling the views, opinions, and rights of minorities (not only religious minorities, but all minorities) is what defines democracy. The idea that ‘majority’ and ‘minority’ are not fixed categories, but that they change – I might be part of a majority on one issue today, but might find myself to be in the minority on another issue tomorrow – all this is what defines democracy. Now, if this is what democracy means, then one has to build a democratic culture. And that is not done in parliament or legislative assemblies. A truly democratic culture is created, fought for, argued over and debated on the streets, in public spaces, in schools and colleges, in places of work, in families, inside homes, and in fact, not just in the drawing rooms of homes, but also in the kitchen and the bedroom. Street theatre, and other forms of live performance, play a vital role here, in forging this larger culture of democracy.

LILA: Every play is a revelation to the public – of their inner fear, anger, despair, their own voice and stance, their do’s and don’ts. Do you take any conscious step to make the mirror gradually acceptable to the public, to ensure a better involvement from them? Or, should every play be neutral to any conscious effort to engage the people, the viewers?

SD: Everything is done for the audience! There’s no point in doing theatre if one isn’t thinking actively and continuously about how the spectators are taking it. What catches their interest, what parts seem to get their attention wavering. And in street theatre, this is even more urgent. The audience hasn’t gathered here after buying a ticket and has no compunctions about walking out mid-way through a performance. Just as there is no entry barrier to street theatre – no ticket, no imposing building, no cultural barrier – there is no exit barrier either! Spectators have many ways of letting you know what they think of your play, and one of them is with their feet. If they stay, something has worked. If they leave, something has failed. So, we need to learn what the Italian theatre maestro Dario Fo used to call the ‘tricks of the trade’ – quite simply, the multifarious ways in which performers of popular theatre hold the attention of their audiences. It is an indispensable skill for street theatre. In Janam, we pay a great deal of attention to this.

LILA: The collective or public memory forms a critical part of the foundations on which public discourses are built. Can the street theatre be used as a pedagogical tool to help nurture the values of peace and critical thinking in the public space, especially in times of agenda-driven rhetoric and fake news?

SD: Ruling classes need to lie, because the truth of their rule is too unpleasant for the people to know. You could say that the American empire – the most powerful empire the world has ever seen – is not premised upon physical occupation and colonialism of the old type, but through the operation of the military-industrial-media complex. The American empire would literally not exist but for the fake news it has manufactured for decades – about the allegedly beneficial role of multinational corporations in the Third World, about the fictional virtues of all manner of despots and dictators, about the alleged villainy of movements for social change in the oppressed lands and by extension the leaders they threw up – from Ho Chi Minh to Allende, from Nkrumah to Fidel Castro. In this scenario, street theatre acts as what Safdar Hashmi used to call the ‘newspaper of the poor’ – something that provides not just an alternative viewpoint, but speaks about aspects of the lives of the working people that hardly ever become part of the dominant media discourse, except in the context of a calamity. In the old days, in working class neighbourhoods or at factory gates, the Left trade unions would stick up the Communist Party newspaper on a wall or a board for workers to read. Workers would read the paper, and then discuss what they had read with other workers around the newspaper, or at a nearby tea stall. Street theatre does something similar – it encourages people to discuss issues openly, in public spaces. That is how critical thinking develops as public culture, by open discussion and debate.

LILA: Many young people are reshaping and reinventing the ideas of street-play by making it more performable and accessible with the audio-visual mode. Do you think that the natural settings of the street-theatre – the smell of heat and dust, the rain and the sun, the sweating viewers and actors, the eclectic sound and the silence of the street, can be reintroduced with audio-visual imageries and symbolisms to meet the need of its time and the people who belong to it?

SD: People sometimes think of street theatre as a ‘limited’ form – because it doesn’t, or cannot, have the paraphernalia that one thinks of when one thinks of theatre, viz. a dark hall and lit stage, formal distance between audience and performers, sets, costumes, makeup, etc. We don’t subscribe to this view, obviously. We don’t think theatre needs to be a prisoner of its own paraphernalia – though we have nothing against the paraphernalia per se. The point of theatre – where it derives its power from – is that it is a live performance, that there is a compelling story that the performers want to share with the audience. In street theatre, it is true we often don’t have an elaborate ritual to create illusion, but we do have something else, in its most raw form – we have the audiences’ imagination. The audience can see that we don’t have any way on earth that we can create a realistic looking warplane or mountain, or create the illusion of a palace or vast agricultural fields – so they are willing to imagine all these things if you know how to creatively excite their imagination. The limits of the street theatre form are set only by the limits of our own creativity. Young artists today are doing amazing work with words, with poetry, with images, and with video. I find it very exciting.

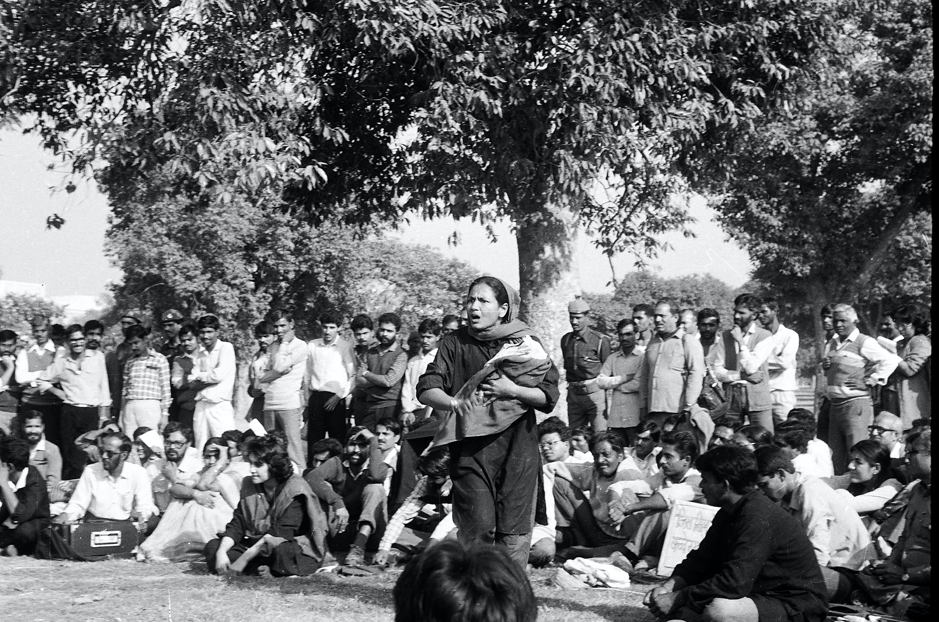

LILA: Women’s rights has been a key issue in Janam’s plays, with progressive and iconic plays like Aurat and Voh Bol Uthi being performed as far back as fifty years ago. Women are considerably more vocal today about issues that trouble them and the society in general, even as violence against women has hit a record high. How do you view the context for women in society today?

SD: Well, Aurat was first performed in 1979, so that’s four decades ago, and Voh Bol Uthi was in 2000, twenty years ago. We have, of course, created and performed many other plays on women’s issues over the last forty years. But what I find interesting, especially in the early Janam work, before feminism had become widely accepted as an idea and ideal, is that Janam has had a gendered perspective – so in a play like Halla Bol, which is about a massive seven-day strike in Delhi, the gender issue is central, and the play critiques the trade union movement, for which the play was created, for its gender bias.

Today, there are signs of change in society at large. Shaheen Bagh and numerous other protests of the recent past have had women in the fore. Every year, in colleges in Delhi University, a whole lot of street theatre is created, and a lot of it focuses on gender. MeToo has played, and continues to play, an important part in raising consciousness, especially among younger women. In most urban families today, the idea of a woman going out to do a job is no longer strange or scoffed at. Women, especially young women, are claiming their place in public spaces with confidence. You could even argue that the fact that the numbers of sexual harassment crimes has gone up is because of two reasons – firstly, because many more women are unafraid to go public and lodge complaints, so there’s more reporting; and there’s also, I feel, a bit of a backlash against the increased participation of women in the public sphere which takes the form of sexual harassment. But I have no doubt that history is on the side of women. They will win – and in the process, humanity will win. And in this, culture and art have to play a big role in making gender-equal ideas acceptable, in portraying positive behaviour as an aspirational goal for men, and in stigmatising misogyny and patriarchy.

LILA: How do you chose the topics you perform on? For instance, while you have a play on the Godhra riots, there has not been any performance on the exodus of the Kashmiri Pandits. As you stand for the oppressed, how do you make the choices on who the oppressed are, and who must be represented?

SD: Honestly, there are too many issues to represent at any point in time. As I point out in my book Halla Bol, Janam, in Safdar’s time, struggled to make a play on the caste issue, and in the end failed. That changed later, and now we have a number of plays on caste, but it took us a long time to get there. We’ve never been able to create anything satisfactory on the climate and environmental crisis. There are so many other issues on which we haven’t been able to create anything at all, or anything of good quality. Sometimes it is a question of trying and failing in the creative department, sometimes you are engaged in something else already and can’t give that up, sometimes for logistical reasons you can’t get your act together. I don’t want to apologise for this. After all, we have done over 8,000 performances of over 100 plays – but it is a drop in the ocean, if you think of the size of the country, or even just Delhi. So what you need are many more such theatre groups that will create politically-engaged work. That’s the only solution!

LILA: How should the street-theatre evolve and register the components and the dynamics of the public’s language, communication, and expression?

SD: I’ve touched upon some of this earlier. All I will say now is that on the one hand, the strength of street theatre is that it is inexpensive to produce, flexible in its form, and easy to mount. This is what enables it to act as the ‘newspaper of the poor’. In a country such as India, where the masses of people are still desperately poor, these characteristics of street theatre have to remain. Within this framework, there is no dearth of creative possibilities, including the use of technologies for amplifying the human voice, to record performances, or to create performances for digital transmission. Having said this, though, I should say one more thing. One reason that street theatre has not faced the kind of targeted attack that films, books, and painting have faced, is because the digital footprint of street theatre is almost non-existent, and that you can still operate a little bit under the radar – but for how long, no one can say. I’d only say that lying low digitally is right now not a bad idea at all!

LILA: How do you visualise the future of the street-theatre in India and Indian street-theatre in any international platform?

SD: Street theatre is a local form, it derives strength from its connection to specific and fairly narrow audiences (narrow as compared to, say, commercial cinema). So long as there is this yawning and ever-increasing chasm between the rich and the poor in India, so long as there are so many sections of our population that face discrimination and marginalisation, so long as there are assaults on people’s basic rights towards life and livelihood, street theatre will remain relevant. It is upon us, the people who do street theatre, to keep its vocabulary and grammar up to date and fresh.