Over the past two decades, governments around the world have been railing against religious extremism. Here in the UK, we now have Islamist preachers serving lengthy prison sentences for delivering lectures online deemed to be encouraging support for prohibited organisations. By clamping down on religious extremism, the aim is to prevent extreme behaviours such as suicide terrorism. But this raises a very fundamental question: are religious beliefs the drivers of extreme behaviours?

It is not hard to find those who argue that acts of suicide terrorism are motivated by extreme religious beliefs. Sam Harris expresses this view succinctly in his popular book The End of Faith: “As a man believes, so he will act. Believe that you are a member of a chosen people, awash in the salacious exports of an evil culture that is turning your children away from God, believe that you will be rewarded with an eternity of unimaginable delights by dealing death to these infidels—and flying a plane into a building is only a matter of being asked to do it.” (2004: 36).

Politicians frequently make similar assertions. For example, David Cameron speaking as the UK’s Prime Minister at the Global Security Forum in Bratislava in 2015 said: “We need to confront extremism in all its forms, violent and non-violent, to stop our young people sliding from one to the other.” The implication is that extreme beliefs readily turn into extreme behaviours. But there is growing scientific evidence that this view may be seriously mistaken – and that the real motivation of extreme behaviour is not religion but something else entirely.

For many years, my colleagues and I have been trying to understand the psychology of violent extremism. As an anthropology student at Cambridge University in the 1980s, I decided to go and live for two years in the rainforest of Papua New Guinea – in a region that had a long and infamous history of warfare. And there I learned something deeply unsettling: the most powerful driver of self-sacrifice on the battlefield is not hatred but an extreme kind of love that arises out of deeply impactful shared experiences.

We all have intense and memorable experiences that shape who we are today. Sometime those experiences are the result of random events such as natural disasters or encounters with wild animals. Sometimes the experiences are manmade, ranging from wars and revolutions to falling in love or attending a rock concert. From ancient times, life-changing events have been deliberately orchestrated in the form of rituals, such as painful initiations or vision quests. Sharing these kinds of experiences with others can bind groups together in powerful ways. But is it also what motivates extreme pro-group action, such as the willingness to fight and die for one other?

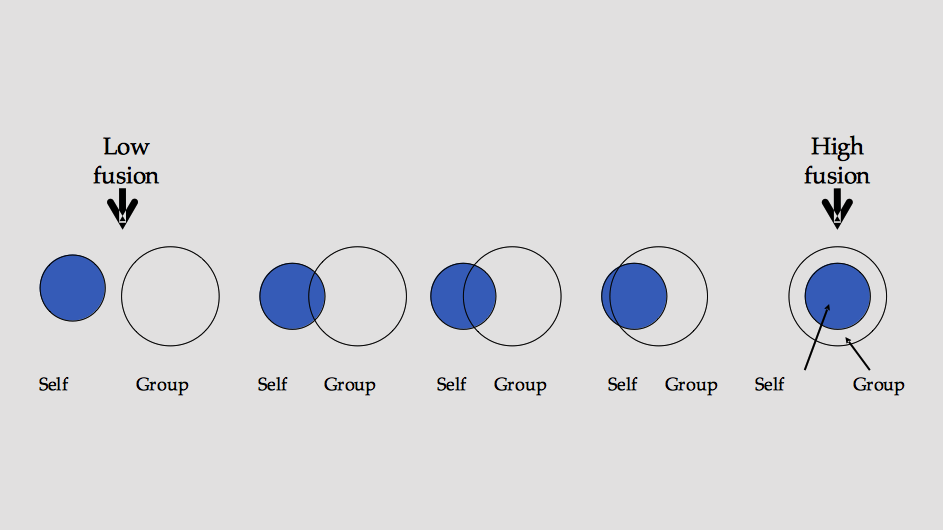

To address that question, I teamed up with group psychologist Bill Swann at the University of Texas. Swann had developed a measure of identity fusion that involved showing people a small circle (that’s you) and a bigger circle (that’s your group), then asking them to pick the one in this series that best characterises their relationship with the group. People who choose the last option are ‘fused’ with the group.

The key to understanding fusion is that we all have personal identities that make us unique as individuals, but we are also aligned with groups. Social identity theorists have shown that making group alignments salient has a depersonalizing effect. But with fusion it’s different. If you are fused then any attack on your group feels like a personal attack. According to our theory, the reason people carry out suicide attacks and other acts of terrorism is because they think that in doing so they are defending themselves and their group (which for them are really the same thing).

Having established that fused individuals in the lab were willing, in theory, to fight and die for each other, we needed to find out if this would be the case in real life or death situations. So, we went to Libya in 2011 – a scene of massive uprising in which thousands of young men and boys willingly laid down their lives to overthrow Gaddafi’s notoriously oppressive regime. We hypothesised that shared sufferings on the frontlines motivated many of these acts of self-sacrifice.

We ran a survey with revolutionaries asking about fusion with various groups. Roughly half the participants in our survey were frontline fighters – the rest provided logistical support for the fighters, for example by driving ambulances, repairing vehicles and so on. We found that all of them were very highly fused with family, fellow fighters, and those from other battalions they’d never met. In contrast, they were not fused with supporters of the revolution who were not members of battalions. In other words, it was not sufficient to be on the same side simply in terms of beliefs or ideology.

Because absolute levels of fusion were so high, we administered a forced choice question. We said: “ok, so we get that you’re fused with several groups, but if you had to pick one – and only one – which would it be?” Frontline fighters, who shared the horrors of combat, were more likely to choose their comrades over family than were those who only provided logistical support. Was this because shared suffering causes fusion (as we hypothesised) or did higher fusion levels in the first place, cause fighters to end up on the frontlines? To find out, we ran a series of studies with US soldiers who had served in a number of conflicts around the world but had no control over their deployment. The results supported our hypothesis that intensity of suffering on the frontline predicted fusion with fellow fighters.

So, with all that research in mind, what realistically can be done about violent extremism? Well, if the root of the problem is shared experience, this may also be one of the best places to start in order to address the problem. First, diagnostic tools assessing perceptions of shared experience and identity fusion at a population level, along with measures of external threat, could be used to identify volatile communities and at-risk individuals prior to the outbreak of conflict. Second, we should consider developing new interventions that focus on life-changing experiences of at-risk individuals, helping them to re-frame their memories of past shared experiences. Third, our framework can be used to expand fusion beyond the ingroup, potentially even encompassing traditional enemies, perhaps building on the many existing initiatives in this area, learning from the strengths and weaknesses both of high-profile initiatives such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa and the many lesser known ones, for instance providing Palestinians with the opportunity to visit the sites of Nazi death camps in Germany and Poland.

Approaching the problem of violent extremism from the perspective of shared experience and identity, rather than religious belief and ideology, will make it easier to engage at-risk individuals and their surrounding communities with programmes designed at increasing tolerance towards outgroups. Instead of arresting preachers, our research suggests we need to reduce shared suffering, the real driver of fusion. Instead of combating extremism with violence, we need to strike at the root of the problem, which is essentially psychological.

What all this suggests is that curtailing freedom of speech may do nothing to prevent or deter intractable conflict in the world. In fact, quite the opposite: A sense of oppression may constitute yet another threat, alongside bombs and bullets, to already embattled groups, fusing them ever more tightly together. For every hospital that’s bombed, every drone strike that misses its intended target, a new cohort of potential extremists is created.