LILA: At the age of 16, you decided to leave your house and go away somewhere. What made you take that decision? What were you seeking?

Bhajju Shyam: No one wants to leave their house, but sometimes the circumstances are such that you have to. After the age of 15, I had started thinking about what I wanted to do in life. I could not study; I had already left it. I worked in the village – the usual work in the fields like planting trees or sowing [crops]. But there were already enough people to do this job. So, I started thinking about leaving the village and doing something new. There were two people from our village who lived in Bhopal. So, I came to Bhopal with them in search of work. When I came here, I first worked as a watchman. Once I lost that job, I worked as an electrician, laying underground electric cables. I had never thought I would become an artist or would paint someday. In between, when I was out of a job at some point, my uncle, Jangarh Singh Shyam, invited me to work with him. There were three artists working with him already, helping him with painting and colouring. They used to do everything – from filling colour to detailing. I thought I could try and see if I could work there, and so I did.

LILA: Before your uncle invited you to work with him, did you ever consider art as a profession worth pursuing yourself?

Bhajju Shyam: No, no! He only called me when I lost my work.

LILA: It is indeed very rare to find people who seriously pursue a career in the arts. Even as you had an uncle who was famous for his art, you were only able to consider it as a serious profession after he exposed you to this work…

Bhajju Shyam: Yes! I did not know what art is, what an artist is, or what painting is – I had no idea. I was a labourer. I entered that space in search of livelihood. I was just thinking that I would get food to eat and a place to stay, and time would pass. I had not even married yet. What does a [unmarried] man need anyway as long as one gets food and a place to stay? In a village, if you are working for someone, you expect money in return. When you come to a city, you first need a place to stay and food to eat. So, that way, I was not so worried about earning money. I just knew that I wanted to stay there and learn some work.

LILA: And when you started working there, your uncle noticed that you also had a talent that you could take forward. How did that happen? Had you started experimenting with your own talent by then?

Bhajju Shyam: No, actually, he used to draw sketches for all, including me. Before he left for office, he would tell us what colour to fill where, how many coatings of daubing to do, and how the outline should not cross the sketch’s boundaries, etc. Initially, my hands used to shiver in fear as I had to do that very carefully. But slowly, as I got better, I also started working on detailing and design as well. This went on for about 2 years, after which, when he travelled out of station for exhibitions or workshops, he would ask me to work on my own designs on A4 paper, in the evenings (He would also caution me not to copy or imitate his works!). So, I started to do that. But, in the beginning, I couldn’t help but make artworks similar to his, because I had learnt from him. I found it very difficult to create my own.

LILA: How old were you then?

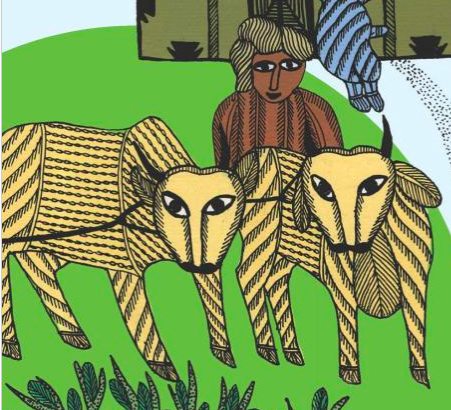

Bhajju Shyam: I was almost 18-19 years of age around that time. Back then, I couldn’t think of how I would create different artworks or how I would create a different colour palette. I was trying to make the same animals, the same trees, hoping that at least something would be different. For a few years, nothing worked. My artworks still imitated his, although I was trying. You know how the way an artist paints – for instance, how you are making a deer, what its shape should be like, how you make an elephant, what its shape should be like – all these become an exclusive design, or a person’s signature style. Like in the case of artists like Raza and M. F. Hussain’s, you can recognise their work in a glance. Similarly, Jangarh Uncle, Anand Shyam, and Narmada are also artists whose work we can identify by just looking at it. So initially, it took me quite some time to emerge as ‘different’. And as I kept working and progressing slowly, my uncle liked what I began to make. Whenever he would go out, he would take my work along and sell it. Once I started getting paid for my work, I also got tempted to continue it.

LILA: How did you manage to find a style of your own?

Bhajju Shyam: I started by drawing trees. At that time, there was a clear distinction between ‘drawing’ and ‘painting’ – if it was a drawing, it would be in black and white, and only pen would be used; and if it was colouring work, it would be done using a brush and colour, but not a pen. I experimented by mixing both of them to create an exclusive identity or style of my own. For instance, I would create black & white patterns and make colourful sparrows inside them. Since both of these works were separate and one had to work on them separately, people admired my work. Then I started exhibiting in groups. People would often call for me at these exhibitions, as they wanted to know whose work that was. I, on the other hand, would wonder what I had done wrong for such renowned people, and people who knew about art and painting, to invite me and talk to me about my works. Whenever I did group shows or exhibitions alongside my fellow Gond-Pradhaan artists, my work was always sold and appreciated by people. This way, it kept expanding. From there, I caught a hold of what worked and slowly tried to give a new form to it.

LILA: Did you grow up seeing the kind of art that you ended up creating, living amongst the Gond community?

Bhajju Shyam: No-no! Gond art, per se, was originated by my uncle Jangarh Shyam. In our village, there is Dīghnā – the way there is Māndhnā. Dīghnā is the relief work one does on the wall and the floor, using various media like cow-dung, mud, etc. There used to be mud-houses, so you would smear and coat them 2-3 times every eight days.

LILA: And every household used to do the relief work?

Bhajju Shyam: Yes, every household used to do that. This was the identity marker of the Gond-Pradhaan houses. I vaguely remember, when I was a kid, Jangarh uncle used to draw special pictures on people’s houses when someone got married or some other ceremony was conducted. For example, if a marriage ceremony was planned, he would draw something like, say, a bride and bridegroom, or trees, or perhaps a deity or an animal. There was no rule as such that you had to draw something for sure. But more often than not, he would. He was fond of it, I guess. Back then, he wasn’t doing a job and also wasn’t an renowned artist yet, so he would draw. I have heard that when he would go to walk the bulls in the fields, he would make sculptures out of clay. Or after his bath in the river, he would lay in the sand and keep making something or the other. I think he loved doing that – making sculptures or doing something else. He’d keep doing something for sure, I have heard from his friends. When the people from Bharat Bhawan came to our village, he [Jangarh Shyam] had made a green-coloured Hanuman. There weren’t many colours available then, so whatever colour you’d find, you’d use it to draw. The people from Bharat Bhawan, working under the supervision of J Swamination, loved this drawing. They were rather amused to see a green-coloured Hanuman. They called for the artist, my uncle, and said they wanted to bring him to Bhopal for a workshop. Quite a lot of artists from Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh were brought there. He had never worked on a paper or a canvas before, and he was handed over a box of acrylic colours – a lot of colours actually. There were hardly 3-4 colours he had worked with back in the village. We used black soil from the mines in the forests because that soil wouldn’t wash off even in the rains; white soil also from the mines; and yellow soil which we brought from the Amarkantak hills. If you burned it a little, the yellow would turn to a shade of orange. Similarly, green colour could be extracted from the leaves of the Sem tree. So, we had 4-5 colours of this type. Cow-dung could be used to parget or smear the surface. When my uncle saw the many acrylic colours, he was simply amused. There was no point in figuring out what colour was for what. So, if you see his earlier works, you’ll notice that there’s a use of a lot of colours! The earlier works were quite flat and there was not much detailing. Someone must have started filling the flat space with details, and he must have followed. He must have realised that it appears even better when you start filling it. This way, an identity of detailing got created. Eventually, he started to create designs and made the use of ‘point’ or ‘dot’ in Gond art. He made that ‘point’ his identity and that ‘point’ got famous. All the artists who had come there [at Bharat Bhawan] created designs of their own. During his time, Narmada, Ram Singh, Anand, Kala Bai, Bhuri Bai, Lado Bai were the 7-8 senior artists who worked there when we had just come.

LILA: I read somewhere that the point comes from a tattooing tradition amongst the Gond–Pradhaan tribe…

Bhajju Shyam: Yes, the Gond-Pradhaan women, do that on their feet and hands, while the women of Baiga tribe make tattoos all over their body. They say that since they cannot buy jewellery made up of precious metals like gold and silver, this is their adornment. So it’s mostly women who get Godnā or tattoos on their body. People say after seeing that, he started using the ‘point.’ Different people have different views on this.

LILA: So, many techniques in Gond art, such as the dots, have come from such observations, and everything you draw is also supposed to hold some meaning. Could you elaborate on these origins and practices?

Bhajju Shyam: Yes! Let me give you an example. Like I mentioned the signature designs that artists have, similarly, I have also created a design out of the dot work we do. You must have noticed a lot of circles or round figures in my work. It is done using different colours. This design represents a man, a woman, and their hands in the middle, which are held together, and they are dancing. If someone asks about this, then I tell them. Everyone calls it a “chain.” I have also created designs out of trees leaves, using the Godnā design of lines. So, I have borrowed some designs from the trees, some from the Godnā. Everyone creates their own designs in this way and makes them.

LILA: Do you think your experience of working in the fields and forests has helped you come up with and create these ideas?

Bhajju Shyam: Yes, of course! If I have to show the spikes of wheat or rice, it doesn’t take me a lot of time to picture and draw it because I have anyway worked amidst all that. If we talk of the forests, I have been to the forests to cut and fetch wood. I would go and wander around alone, in spite of a lot of wild animals residing in there. So, we do keep taking inspiration from all these places for our subjects and working on them.

LILA: How do you think that distinction between a ‘contemporary artist’ and an ‘artisans’ is made nowadays?

Bhajju Shyam: See, I am not very well-read about this. But, ‘contemporary,’ as they say, are artists who study, go to an art school; they learn about each colour, each line; about whether it’s a day or night and how do you show it; how do you show a shadow or a point. They study about all this. Our work, on the other hand, is direct. Whatever we want to show, it should be obvious to the audience – be it an eye, or a foot, or hair – it should look as it is. Our work is to fill details within that picture; that’s our identity. When you see the design, you can identify it as my work or another artist’s work. Right now, there are almost 20-25 artists for whom you won’t necessarily need to ask the name as you would be able to identify them from the artwork itself.

Nowadays, the work of most artists, including me, is also being copied; people copy from Google. But, I’d like to say that this happens with everyone in the beginning. Even we used to copy because we did not know anything. We couldn’t create something out of our mind. I think once you want to be an artist, or once you work starts getting appreciated, you will have a responsibility, and eventually, you will think and create something new. Otherwise one can easily earn money by copying someone else’s work, but one can’t earn name or fame that way. If you want to do the latter, you will have to create something new.

LILA: As you mentioned your uncle’s cohort, whom do you see as your contemporaries? Do you see them both within and outside of Gond art?

Bhajju Shyam: If I talk about Gond artists in particular, they are mostly people I know, friends or relatives, that are working on this. There are artists like Raju, Dilip, Mayank, and Roshni. I’d say there are almost 150-200 artists today, all the way from the villages to Bhopal. They also go to different countries and work. Certainly, there are people from “outside” as well. As we conduct workshops, we come across Madhubani artists and artists working on other forms of art. We have also exhibited together and conducted workshops together.

Over the last 6-7 years, Gond art has received recognition from across the world. Earlier, only people within the Indian government organisations like Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, Crafts Museum, or Delhi Haat, etc., were aware of it. They would invite artists to work with them. However, now, everyone – be it government, non-government, or private institutions – has started to associate us alongside the contemporary artists.

LILA: Have other people also started to come out of your village, and considering art as a serious occupation?

Bhajju Shyam: Yes, a lot of them. Actually, they have made this a way of life, and of strengthening their financial status. During our times, we boys used to work in the fields, go to the jungle, earn some yield, and used to do everything from ploughing to irrigating, etc. Kids these days, however, don’t want to do that much physical work. When we lived in the village, there was poverty. That’s not the case anymore. Now, young men prefer doing lighter work. Ever since Gond art gained recognition, almost 10-15 years ago, all the young men and women from the village have entered the field. They are painting, they are getting name and fame, earning a good amount of money, and travelling across the country to exhibit their work. So everyone has made this a way of livelihood as well as a career. They want to take this ahead. Most of them have been successful in this regard. Also, ever since I received the Padma Shri award, all the artists have started getting more work. So quite a lot of artists got benefited from that as well.

LILA: You have also come to learn about and interact with art styles other than Gond art. As you mentioned earlier, Gond art has a very direct aesthetic, as compared to other art forms. When it comes to understanding different art styles and the message behind them, it seems to be easier to convey a message using Gond art because of its direct aesthetic. How do you view this?

Bhajju Shyam: Yes, I do feel the same. Some artists want to convey the message in the ‘hidden’ form, while we want to show and convey it directly. They do not want to make it obvious. They want to show a reflection perhaps, say, if a man is walking, they would just show his reflection in the mirror, while we would show it clearly. They want to show it by hiding it. I think they are also right in their place. Those who study modern and contemporary art also see things that way. We do not have that sight, that gaze to see it that way. We can only see clearly, which is what we try to show in our works. We believe in that. We do not believe much in what isn’t visible or cannot be seen, unless a need arises.

LILA: As Gond art gains recognition world-wide, do you also think it has helped the community reconnect with its traditions, especially at a time when the youth is reaping the benefits of development and given up other traditional occupational practices?

Bhajju Shyam: No, actually. Gond art has made a return for sure. People from across the world come to the village now to meet us, so awareness about the paintings has spread, but they still aren’t aware of other things, including our language, our stories, our proverbs, our poems, our songs, etc. They also don’t want to learn any of that. It’s good to promote the paintings, but I think they should do it by keeping their traditions in mind; by associating themselves with the traditions; and by associating traditions with their work. The kids these days, contrary to our times, only pretend to show respect to our Adivasi traditions, and that is the common scene across villages. Now that there are well-paved roads, they race motorcycles around. Accidents are happening and whatnot. Things have changed. The new artists should work on painting while paying attention to their language, their deities, their trees, their songs, and their bhajans. If they work with them, I strongly believe, our traditions will reach various parts of the country and the world. I have tried my best – twelve books have come out now and through them, people throughout the country have started to read about us and our traditions. If I am describing a painting, that painting has my story and the story of my traditions. Those stories are being read by students in schools and colleges across the country. I often go to different schools and there they have question-answer sessions, I get asked questions and I feel good. So, through this, people have started getting to know about us, our identity, our traditions, our songs, etc. I am doing this and if other people also start doing it, I am sure that this will go further and there will be our name all over the world. I feel that.