It is in the nature of guerrillas to transgress. Their irregular combat, driven by a strong sense of purpose, works outside of the normal, symmetrical limits of war. And, since 1985, activist-artists Guerrilla Girls have founded their outrageous warfare against sexism, racism and tokenism in the art world, on asymmetry—in the true guerrilla fashion.

It is ironical to suggest that a ‘founding’ process can be ceaseless, or that any purposive battle can be established in irregularity. But for the Guerrilla Girls, who call themselves the ‘conscience of the art world’ in quite a matter-of-fact manner, irony is fact, and fact, irony—at multiple levels. Using well-researched fact sheets and statistics that embarrass people in positions, the GG consistently shame the art world for its under-representation of women artists and people of colour. The Girls go on, wearing gorilla masks, adding posters, billboards, performances, protests, lectures, books and installations to the extraordinary GG oeuvre, and forming their variegated selves into, perhaps, the singular, most effective, anonymous collective of vigilantes on the global art scene today. The Guerrilla Girls are The Economist of the art world—they take stock, they hit where it hurts real good.

The Girls are all practicing artists in their unmasked avatars—probably, painters, photographers, designers that you know and admire, but would never come to recognize as they don the gorilla masks and go about throwing light on the dark corners of the art world where discrimination lurks. They are a veritable women’s secret society based in the US but serving the art world across borders. And, how does one enter this guerrilla group? They don’t do interviews or place ads. If asked how they manage to get people into the fold, they simply say: “When we require help, we look around for the skills we need as well as a firm commitment to inter-sectional feminism with the courage to complain about the art world. And very important: a willingness to work collectively and without getting personal credit. It’s not about recruiting top talent or creating a power circle.” It might sound chaotic, but that is the organic mode of these guerrillas. Inside the fold, every Girl goes under a chosen nom de guerre of a dead female artist and becomes a guerrilla. So, you see a gorilla-faced Frida Kahlo, Käthe Kollwitz, Gertrude Stein, Zubeida Agha, Alma Thomas, Rosalba Carriera, Alice Neel, Julia de Burgos, Hannah Höch, or Shigeko Kubota speaking with the press, leading a march, putting up GG posters with twisted headlines and outrageous visuals, taking a ‘weenie count’ in a museum to get the killer GG statistics. These names serve the Girls’ practical purpose of interacting with one another as well as with the world about them while they are on their espionage mission, but they also help evoke some artistic legacies that the GG would like the world to never forget.

The GG were guerrillas before they started wearing their gorilla masks. The Spanish term ‘guerrilla’ that comes from ‘guerra’ meaning ‘war’ became popular during the early-19th century when the Spanish and Portuguese people rose against the Napoleonic troops using a strategy that magnified the impact of their small, mobile force. The guerrilla warfare is asymmetric because the fighters dare to take on opponents with unequal strength. But they weaken their enemies by attrition, eventually getting the better of them. Beyond simply winning a war, a guerrilla aims to gather people’s support and create political effect at the enemy’s expense. Hence, it is of utmost importance for them to nurture their mobility, secrecy, and capacity to surprise, as well as to tactically employ harassment, local attacks and chase, towards gradually depleting the strength on the other side.

And, that is exactly how the Guerrilla Girls work. In an article titled “Transgressive Techniques of the Guerrilla Girls”[1], Frida Kahlo and Kathe Kollwitz explain the methods that they use to break new ground in protesting against sexism, racism, tokenism and such ills in the art world. Kahlo and Kollwitz categorise the tactics and tools of their guerrilla warfare under six heads:

- The Art of Creative Complaining

- Facts, Humour and Outrageous Visuals

- Reinventing the Textbook

- Repurposing Museums

- Infiltrating a Venerable Institution

- Outsider Art

The Girls complain, indeed, but they make lamentation appear like a style statement. A glamorously outrageous wailing club that tempts one to join in. As New York Times art critic Roberta Smith noted, the GG took “feminist theory, gave it a populist twist and some Madison Avenue pizazz and set it loose in the streets.” That is culture jamming at its best; creative subversion at its peak. And, it worked, it is working, and as long as discrimination exists, it will continue to work.

The Girls work with facts and figures. So, no one can refute them. They are a set of feminists with a great sense of humour. When Guggenheim SoHo opened, they infiltrated its bathrooms to place fact-stickers concerning female inequality on the walls, so people had time to see. They make it all sound so wicked, look quite laughable. But, at the end of the day, they get their following from the most unexpected of places. They use wit and humour to make even their critics laugh, thereby reducing the intensity of possible backlash. Yet, when you look closer, you see that it is no laughing matter that they have been dealing with.

Every day they unearth new, newer, herstories—meticulously rewriting the white, male stories that histories have been for a long long time. They make a book like The Hysterical Herstory of Hysteria and How It was Cured: From Ancient Times Until Now that tells the true story of how female bodies have been treated over centuries, and proposes a new outlook for the future of reading. Their Art Museum Activity Book takes you behind the alluring pictures, tempts you to “wallow in the dirt” that the museums hope you would not notice, and gives you “great ideas for how you can bother, and maybe change, your favourite museum”. They write a Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art, which Mark Dery describes as “a levelling indictment of bigotry in the art world,” in the New York Times Book Review, and congratulates the GG for their work that “elevates cage-bar rattling to a fine art.”.

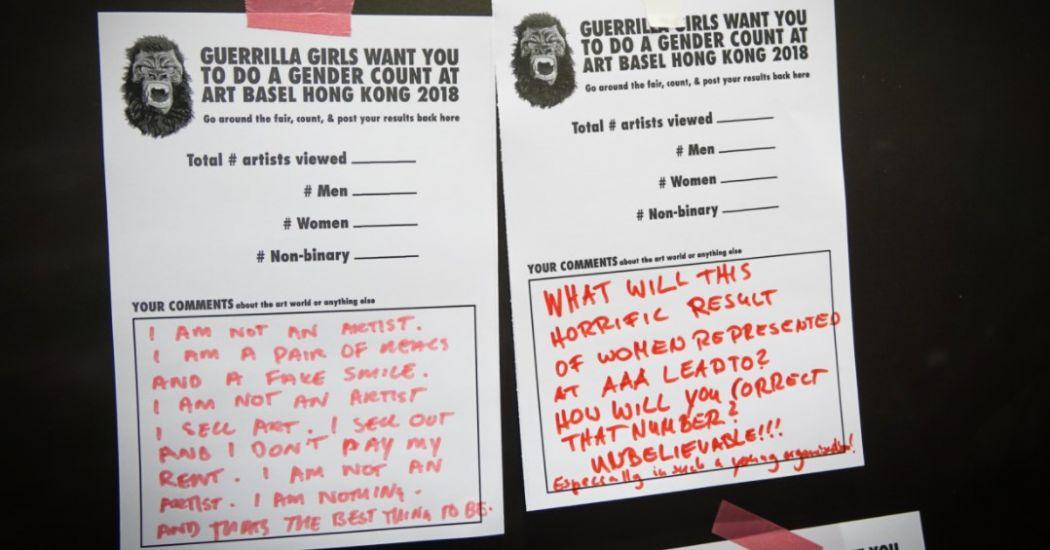

With time, the GG have looked beyond the art scene to spot their targets. Today they take on Hollywood and right-wing politicians, and they do a gender count at Art Basel Hong Kong 2018. They work with spaces that once ignored them, including the Tate Modern and MoMA, and yet do not change their guerrilla tactics, noms de guerre or their gorilla masks; they growl just as loudly, even as they are inside these venerable institutions whose walls have come to display their ‘outsider art’.

Photo: Koel Chu/HKFP.

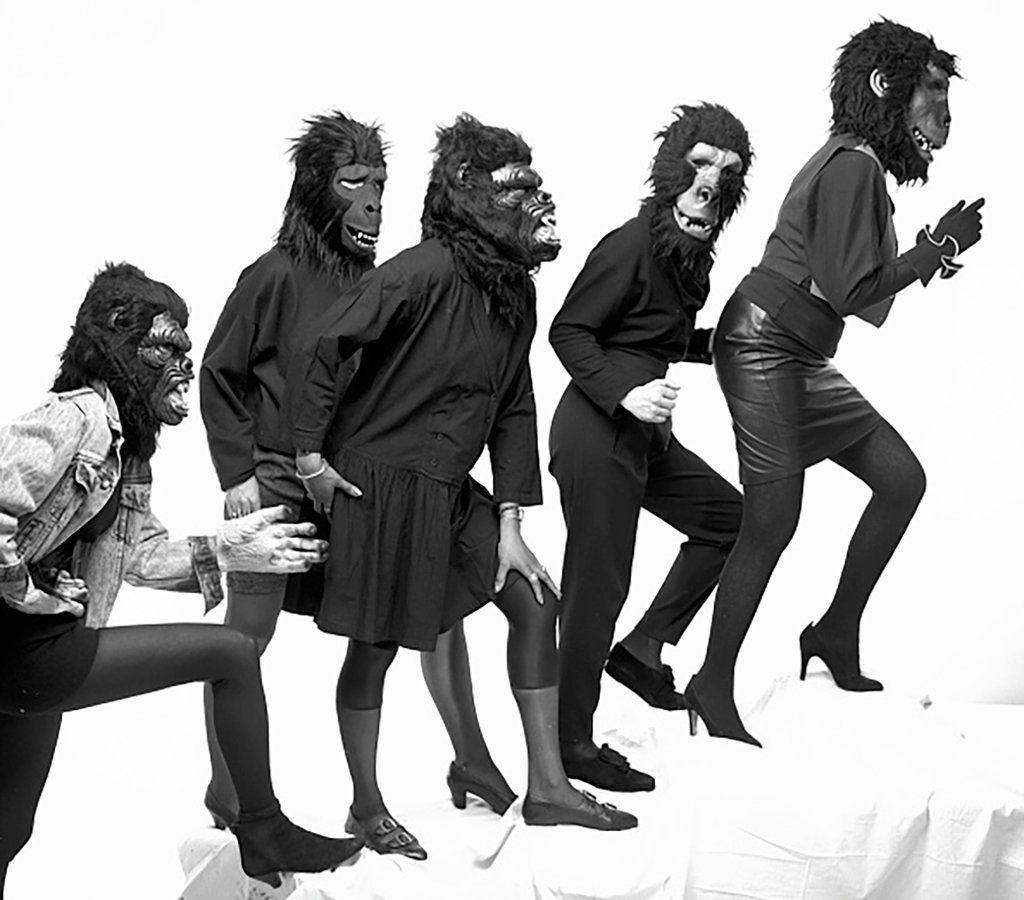

The Guerrilla Girls communicate and market themselves in a highly sophisticated and witty manner that, arguably, no other feminist campaign in our times has matched. Their posters and hoardings appeal to an educated viewer like advertising to an urban consumer. Their public appearances wearing gorilla faces are crowd-pullers; they lure, and keep luring more and more people, as they appear in strategic spots.

How the GG began wearing the fur is not exactly recollected, but the story goes: At an early meeting, one of the Girls, a bad speller, wrote ‘Gorilla’ instead of ‘Guerrilla.’ That was a luminous error that offered the Girls a chance to wear their “mask-ulinity,” and helped them exploit the constitutional provision of anonymous speech to the maximum advantage of women artists and gender-equality activists all over the world.

The masks seem funny at first sight. But the gorilla symbolism has become quite a powerful aid in revealing the profundity of the Girls’ work. It is significant that in Ancient Greek ‘gorilla’ meant ‘’tribe of hairy women’, and its first usage dates back to the Carthaginian explorer Hanno (c. 500 BC) who came across some “savage people, the greater part of whom were women whose bodies were hairy” while on an expedition on the west African coast. Today, when the Guerrilla Girls walk the streets, their mask-ulinity not only evokes the original people who inspired the making of that term, but also challenges the typical contemporary association of the gorilla with masculinity.

The pseudonyms of influential female artists add to the theatricality of the GG presentation. When they wear the faces of these large, furry, powerful jungle beings, their bodies call for an appreciation of the natural forms of all animals and lead you beyond the conventional notions and constructs of the beauty of the human female. They also draw your attention to the key mimetic function of art as articulated by many ‘masters’, and remind you that if art is the imitation of nature’s ways, then anything that under-represent or discriminate against the female of the human species cannot be considered art. The Girls inspire you to get rid of your prejudices and transform yourselves. In fact, their mask becomes a metaphor of the transformation that they envisage in the art world, even as it takes one to a certain linguistic trivia: the Arabic transitive, masakha, means “he transformed!”

The Guerrilla Girls’ first colour poster responded to the astonishing number of female nudes in the Modern Art sections of the Metropolitan, by shooting an embarrassing question: “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?” On this iconic 1989 poster is an image of the Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres painting La Grande Odalisque, one of the most famous female nudes in Western art history, but with a large, snarling gorilla head placed over the original female face.

The juxtaposition of the gorilla head and the odalisque body dramatically alters the way you see the highly sexualised image. It questions and modifies all stereotypes of female beauty constructed, disseminated and preserved through time, across cultures.

The gorilla face has helped the GG function effectively in multiple ways. Yet, at a time when everyone is trying to collect her achievements in one visible place, what stops a brilliant mind who joins the GG fold from claiming the individual glory of being an effective force in today’s world? This capability for self-transcendence seems to come from a deep-seated knowing every Girl has about the killing effects of institutionalising creativity, as well as a profound conviction about the efficacy of the guerrilla warfare to protest against that.

Photo: Jack Mitchell. 1990

The play, disguise and spectacular style of the Guerrilla Girls are ways of channelling their indignation in creative, operative ways towards bringing about transformation. In their vision of change, their own acts are not placed in polar opposition with anyone’s. They constantly bring the distances between opposites closer. And, towards doing this more effectively, and addressing critical questions more intensely, they emphasise the importance of local activism. The Girls are a moving example of deinstitutionalised feminism that reinvents itself ceaselessly. In the face of enormous systemic inequalities, biases and discriminations, they go about doing something small, something that moves, and moves well, at the local level. They complain to the authorities at home. They play pranks in the neighbourhood. They make affordable art and share it with the passers-by on the streets. “Over the years we’ve figured out a way to get by as a group, doing small exchanges rather than large exchanges,” Kathie Kollwitz once said. “We don’t live off huge sums coming from patrons. We engage in a lot of small exchanges: we sell T-shirts and posters and books, and we have lots and lots of people to support our work.” You got to hand it to the GG–they should know the trick, for, this has been their mode of survival and victory for decades.

Naturally, the lack of linear organisational structure could result in strong views being voiced strongly, conflicts and delays. But, as we know by now, the Girls are not worried about saving any institution or structure; they fight an irregularly earnest war for the rights of the underrepresented. And, thrilled by their own daily guerrilla adventures, they charge ahead in their mask-ulinity; they find interminable meanings for the ‘F’ word, as they go on, creating a new (F)antom paradigm for the futures of females, and all things discriminated against, generation after generation.

The Guerrilla Girls in their Own Words:

The Guerrilla Girls are feminist activist artists. Over 55 people have been members over the years, some for weeks, some for decades. Our anonymity keeps the focus on the issues, and away from who we might be. We wear gorilla masks in public and use facts, humor and outrageous visuals to expose gender and ethnic bias as well as corruption in politics, art, film, and pop culture. We undermine the idea of a mainstream narrative by revealing the understory, the subtext, the overlooked, and the downright unfair. We believe in an intersectional feminism that fights discrimination and supports human rights for all people and all genders. We have done over 100 street projects, posters and stickers all over the world, including New York, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, Mexico City, Istanbul, London, Bilbao, Rotterdam, and Shanghai, to name just a few. We also do projects and exhibitions at museums, attacking them for their bad behavior and discriminatory practices right on their own walls, including our 2015 stealth projection about income inequality and the super rich hijacking art on the façade of the Whitney Museum in New York. Our retrospectives in Bilbao and Madrid, Guerrilla Girls 1985-2015, and our US traveling exhibition, Guerrilla Girls: Not Ready To Make Nice, have attracted thousands. We could be anyone. We are everywhere. What’s next? More creative complaining!! New projects in London, Paris, Cologne, and more!

Courtesy: www.guerrillagirls.com

All images courtesy: Guerrilla Girls

[1] Getty Research Journal, No. 2 (2010), pp. 203-208 (6 pages), The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the J. Paul Getty Trust