LILA: Thank you, Ron, for agreeing to be a part of Inter-Actions. In our current issue on ‘Language’, we are happy to feature your representations of the Naga people of the Konyak tribe. You have spent time among the Konyaks and have photo-documented them. Why did you choose this subject, and what factors interested you most as a photographer? What was your approach while photographing the members of this ancient community?

Ronald Patrick: My work on these communities came half by accident and half because of a deep interest and curiosity about what is happening in different parts of the world in terms of vanishing cultures and traditions of which we still have a lot to learn from. In 2015 I started an overland trip from Cambodia to Europe (finally made it to Siberia in the lapse of one year), and as I slowly moved from country to country, I encountered diverse topics that had to do with how we, as a society, are changing. While traveling through Myanmar, I met someone who suggested to me that I should definitely go to Nagaland and meet Phejin Konyak, a researcher and local from Shiong Village in the middle of Nagaland. It also happened to be that Nagaland was exactly on my path and I immediately felt I had to go there. I had the chance to spend a little over 5 weeks in the region, visiting different villages but staying in one particular village most of the time. For a project like this, 5 weeks is very little time, but since I met Phejin, she granted me access to a lot of people including her own family and information that was very valuable.

What really interested me is that this community, being a very isolated one, is experiencing incredibly fast and radical changes to their daily life due to religion and the arrival of technology, which translates into cultural and social alteration. These changes are visually very evident, and that makes it very interesting for me as a photographer. I am very curious to see these changes, and to understand why they happen by interacting with the community. In order to do this, my approach is very similar and straightforward each time. I try to spend as much time as possible with the people and take some time talking and being with them before photographing. I always take the time to explain why I’m there, and I openly explain my intentions. If you show yourself in an honest way, you’ll get honest replies back and their attitude to be photographed will also be more positive and natural.

LILA: Do you see elements of Animism in the Konyak culture even today? As someone who has travelled and interacted with various peoples across the world, do you see similar lifestyles elsewhere in our times? How do they balance their ancient animism and their new Christian way of life?

RP: My first interaction with an animist culture was in Nagaland, so I consider myself no expert on this topic. As an observer, I think that animist cultures share more or less the same principles, which are: deep respect and understanding of nature, and a very sustainable and balanced way of life – maybe because they live by nature’s rules and are observing its evolution every day. This is translated into practical solutions and management of many aspects of daily life. This knowledge has been transferred from generation to generation. By this, I’m trying to say that animism is a way of life, and I feel it is very alive in this culture, even though in Nagaland it is being suppressed by Baptist Christianity, which is pretty much the opposite. There, I experienced a very interesting duality between animism and Christianity.

As an example, one day the community gathered to sow rice in the fields of one of the villagers. This work has been done communally for generations in that region, but today is an activity that is somehow organised through the church. It was an intense day of labour, where around 50 people participated (mostly women). During that day, a pig was sacrificed, firstly as an animist tradition to please and thank the spirits, and also in order to feed the people who were working that day. This sacrifice is absolutely forbidden by the Christians, but the Konyaks made an exception to this rule, as they do in other aspects of their lives, too.

The balance though is quickly shifting to the Baptist side. Every Sunday, outside the church in Longwa village – the church is by far the biggest building in the village, and positioned atop a hill – there is a small flea market where villagers, mostly women, sell objects related to their traditional way of living. They are selling these because they’ve been told that these objects are demonic and lead people away from the path of Jesus Christ. So they are selling their precious cultural objects for almost nothing, just to get rid of them and move on, accepting what they have been told is correct. I feel that at this point, even though they are trying to get rid of these objects (and thus, their culture), they still live in a duality since they have such strong roots to their past. Most of the population goes to Mass every Sunday but also attends and celebrates the Hornbill festival and other traditional celebrations each year.

LILA: You have noted that radical changes have come over the Konyaks over time. These people who were once headhunters seems to be fast losing their old identity. Could you explain this change? How does this change reflect in them?

RP: When I arrived in Nagaland, I wanted to do a series of portraits and asked my subjects from different generations to describe the most important change they had seen in their life and how it had affected them. When I put this question to a number of people, I got similar answers from people in the same age group.

Members of the older generations, some of them actual warriors with incredible faces and body tattoos, which proved their bravery and heroic actions, told me that in the past, when there were conflicts between villages and head hunts, people lived in extreme uncertainty and fear. People going to work in their fields could be ambushed and killed by a warrior from a nearby village. So in that sense the coming of Christianity definitely brought peace to these communities and pacified the whole region. For this the older people are very thankful. Although there was that very positive side to the coming of Christianity, there are also the very serious question about how this penetrates a culture. I talked with Konyak Baptist preachers (who also had tattoos from their earlier life as warriors) who would tell me that the most important thing now was to follow the word of Jesus, to study English, and to forget all about traditional Konyak songs, dances, poetry and even dialect, because they had to move forward into modern society. This completely changes the story, because when the Konyaks start getting rid of their traditions and culture, they’ll start losing their identity.

Some old people do go to church on Sundays, while others don’t believe in Christianity and stay home minding their own life, but most young and middle-aged people will go to church. They have changed their habits, which is definitely changing their identity.

LILA: The tattoos on the Konyak people are a language of its own. Do you think, this language, which talks about the specific heroic acts of individuals, is of any relevance in today’s world? As a contemporary professional how do you see their worldview?

RP: I think it is relevant in the sense that the tattoos worn by these old warriors are a living part of their tribal history. Also, not all tattoos have to do with war. The tattoos worn by old women in the community are markers of the different events in different periods of their life, such as the coming of age, marriage, having their first child, and so on. The tattooing practice was inherent to Konyak culture, traditions and identity, so I do think the tattoos are relevant in today’s world.

I met a teenager whose grandfather, a former warrior, was very proud of the tattoos covering his chest and face. The boy himself had two tattoos, both very badly executed (probably by himself or by a friend): one was a Christian cross and the other was Batman’s logo. This is a sign of what is relevant or important for younger generations. Like his grandfather, the boy will wear these tattoos for the rest of his life. I find this paradigm shift in Konyak culture very interesting, but from my own perspective, I find it very sad, and it worries me. This is a question that could be very well addressed by Phejin Konyak.

LILA: We did not see any school scenes among your photos? Are the Konyaks literate?

RP: There is very little educational infrastructure in the villages. Children will have to go far away, into bigger towns or cities to get state education; as an alternative, there are a few boarding schools also. This area, as I was also told by locals, is neglected by the Indian authorities, and resources – including health, eduation, basic needs and road infrastructure – are extremely limited. For these reasons, education is very poor in this part of India.

LILA: We understand that there are a lot of dialects of this language, which are fast becoming extinct. What is your experience of speaking with the tribe? Are there different sections in the tribe? How did they communicate with you?

RP: I was lucky that I always found someone who spoke English, and was willing to translate for me. Yes, there are many different dialects, varying from village to village, and they are becoming extinct for the reason that they are only spoken by the older people, because younger generations are migrating to the cities and have no interest in keeping their language (of course not all of them). Clearly, for those who move to the cities, it is more useful to know English and Hindi. Some of the young people I met in the villages were happy to speak to me as this was a way to practice their English.

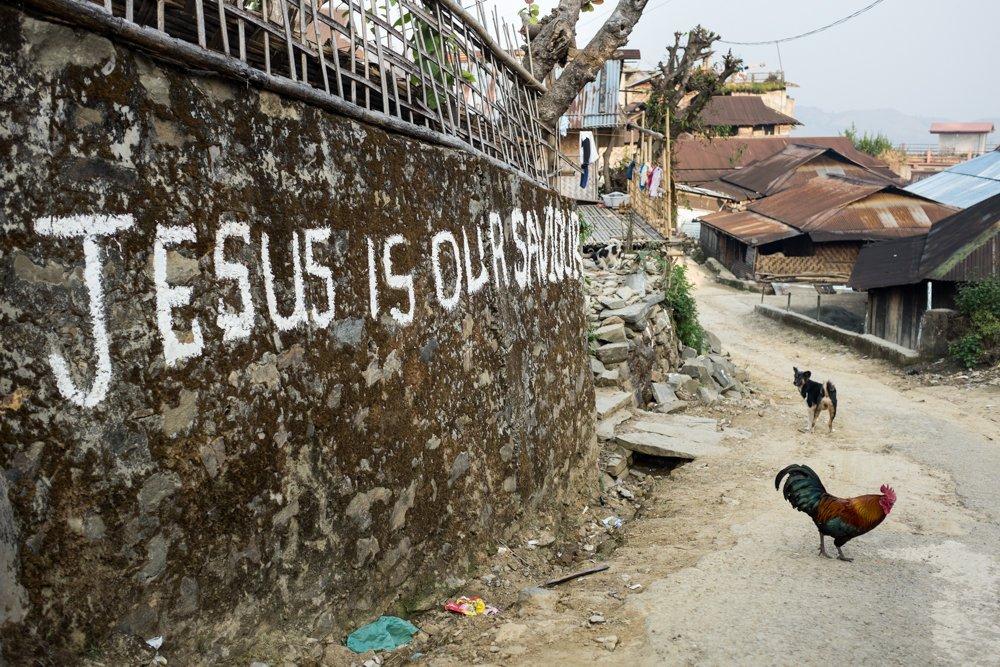

LILA: In your photos, we find Christian-themed graffiti in English on the walls. Do the people speak in English or Konyak? Is there a conflict between the older and younger generations on this count?

RP: People in the villages speak in their own language/dialect. I don’t think there is a conflict in this regard. On the contrary, I think the older generations are proud that their children and grandchildren speak English. In that respect I guess the message is out there in English for the younger generation.

LILA: You mentioned that the invasion of technology has destroyed their culture–even your camera is technology. Do you think this is unavoidable in our times? Also, what is your take on keeping a group of citizens of this country away from technology and other advancements in thinking and living? What would be a balanced way of mainstreaming/protecting isolated communities?

RP: The religious aspect is only one aspect affecting these communities. There is also the arrival of technology and television in their lives. TV, I believe, can have a huge impact on a community that has never lived with it (or didn’t grow with it) in a big way. First, it is changing the way people interact inside their households where the TV set has become central and it affects the way families communicate. I remember a large family gathered around the TV not speaking a word while watching a Hindi soap opera or the Spanish football league. The access to good programing is indeed very limited too. Then there is the consumerism aspect. Children and younger generations see what is offered, and are bombarded with TV commercials about products that have now become a ‘necessity’. The problem is that these families don’t have the income to cover the cost of buying these ‘necessary’ products, unless they go into debt. But there is nothing new about it, as this is happening worldwide.

Many young people are moving to bigger towns or cities in order to get formal education, and the tendency is that they would stay in those places and come back to their hometowns just to visit. It is perfectly normal that people want what they see on television, specially the way that television sells the products and lifestyle to society. I think that this is unavoidable, and we cannot decide for other people what is better for them. We’re all free to choose what we want for our lives. What I do think is that the speed with which technology is reaching different communities and societies around the world is faster than how they can adapt to these changes. I wish I had an answer to finding a balanced way of mainstreaming/protecting isolated communities, but I think its a very complex issue.

I’m no one to judge what is better for the Konyaks, but I can talk from my own experience, on how some aspects of technology have had a negative impact in my own life and in the Western society I live in. Undoubtedly, technology can have an incredibly positive effect on people’s lives, but there are some other dimensions of technology that are very mean and predatory. There are many companies managed by a few greedy individuals, for whom communities like the Konyaks are simply material to exploit. Many such communities barely have basic resources (e.g., education, health, access roads), and are not in a position to take good decisions on whether or not to buy what is offered to them. It is a very complex problem.

I also think that when we visit and experience such communities for short periods of time, we tend to romanticise their way of life that to outsiders seems ‘exotic’. We rarely consider that the permanent living conditions of these tribes are very hard, and that some modern changes would benefit the people in these communities. But what personally affects me is when I see extreme changes introduced that completely shift the way some people live, changing also the sustainable lifestyles led by these communities that we inhabitants of the modern world need to learn from and reincorporate in our lives. But we won’t have the chance because these cultures have already shifted to the ‘modern world’, and their good practices may change forever.

Another example related to the impact of technology is the way houses are now being built in this area. Earlier, houses were made using natural fibres from the trees for both walls and roofs. These materials would have to be repaired and replaced periodically, and this of course requires labour. But they would serve their purpose, keep the house cool in the summer and warm in the winter. They could easily be extended when the family grew, and this was central to the lifestyle of these communities. Today houses are being built with bricks and have tin roofs that, without the proper insulation, are very hot during the summer and very cold in the winter. These are cheap materials and a modern solution that may look attractive, but in reality do not improve people’s lives. There are technologies that are being widely used and adopted by the local communities, but is it making their life better?

LILA: A question about your photographic language. You have black and white as well as colour photos of the Konyaks. Is there a reason you made this distinction in treating your subjects?

RP: I had intended to shoot my portrait series in black-and-white, in a square format, using an old Rolleiflex camera in order to give the images a timeless feel. Also, I personally feel that when I am actually photographing, this camera is less intrusive. I like to create an effect, as if these black-and-white pictures could have been taken years ago. But there will always be details in the pictures that reveal that they have been taken recently. I also like to mix up formats, and to arrange the colour and black-and-white pictures so that they are in dialogue. After all, my subjects are old tattooed warriors who also go to church and watch the Spanish football league.