Visualise a theatre performance. The first thing that comes to mind is probably an auditorium with a stage and space to seat the audience. The audiences buy tickets and obediently seat themselves at the designated spots; the performers remain at a distance from them, clearly separated by the stage. There is no intimacy between the performers and audiences other than the shared experience of the story being narrated. This is the typical setting of the British tradition of theatre, now popularised across most parts of the world, where the theatre is the product, and the audiences or supporters of the theatre are the buyers. Even today, theatre in India is either supported by audiences who pay for a star-cast or through financial aid provided by the government or organisation promoting art and culture. This is in stark contrast with the historical tradition of theatre in India.

Unlike its modern adaptation by the market, theatre in India was a way of building companionship and unity within communities in different parts of the country. It was a way for the masses living in villages to come together and share stories and pass on traditions. In Odisha, there are more than 10 folk theatre forms that continue to exist across its villages. These have been in existence for the last 300-500 years and are produced by rural artists, largely away from the modern/mainstream. These forms have never followed rules of the market system, as we know them today. Instead, their financial sponsorship came from the public at large. Supporting the arts was like a part of life and duty of each villager. Therefore, each member would contribute to the production based on their individual financial capacities and become a shareholder in the process. All villagers would enjoy equal rights to witness the performance or any cultural event irrespective of the amounts they had paid.

This shift runs parallel to the way markets have evolved within village settings in India. The villagers have historically never been familiar with the kind of market system we see around us today. When ‘currency’ got introduced in our social system, the then decentral economy came under the control of a small section of people and the language of the market narrowed down to that of finance. The traditional village markets, however, were never limited to the exchange of commodities. If we think of the weekly village markets (Hata) of rural and tribal regions of Odisha, it is evident that market is not only for business. The Hata is a popular place for social gatherings, entertainment, marriage propositions, catching up with friends, and many such activities. Unlike the malls and supermarkets, where one has to be more silent and “civilised”, the weekly Hata is a place of dance and music; it is a centre of exchanging information to reach many people in the quickest time; a knowledge exchange centre where people share advice about each other’s livelihood activities or discuss family problems; it is a place of health, care and much more. It allows the space to accommodate games of bargains between the buyers and sellers, therefore also enabling a compassionate and considered exchange, not solely dependent on the MRP.

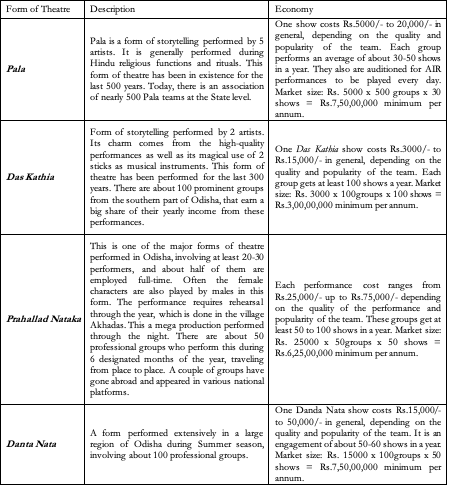

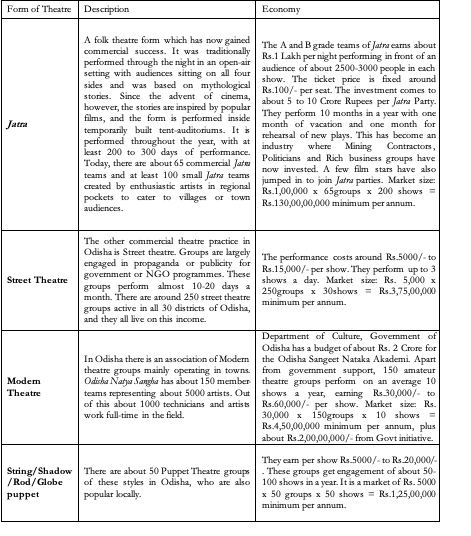

Now, due to market pressure, that spirit has started to decrease, both in the village markets as well as that of arts and culture. Even though folk theatre continues to thrive in Odisha as village masses still connect it with rituals and special occasions – Ram Lila during the birth period of God Rama, Krishna Lila during Krishna birth time, Pala played for a new born baby, Prahallad Nataka for enjoying the summer and winter with Dasahara/Durga Puja, Danda Nata during the hard summer time etc. – it is still not considered significant for the economy. The graphic below details how inaccurate such a conception is. Let us look at the economy of theatre within Odisha itself:

Like the above examples, there are more seasonal theatre forms like Ghuduki/Duari Nata, Desia Nata, Ram Lila, Krushna Lila, Bharat Lila, Sanchar Nata which bring in a total earning of minimum Rs 15 crore cumulated by between 10-50 theatre groups for each style. So as a minimum calculation in the field of theatre in Odisha, one of the poorest States in India, there is a turnover of about Rs. 160 crore a year. Then there is an additional economic structure around the venue of the event when other businesses run like temporary restaurants, snacks, refreshment stalls, daily usable shops etc. But the government still thinks artists are unnecessary as they are not connected with economy.

The second concern with respect to the contemporary market forces and the arts and culture sector is the top-down approach to artists. Market does not recognise village art. It gets the title of ‘Folk Art’ and is expected to bear a certain ‘primitive’ value. Instead, highly paid artists belonging to urban markets set models for villagers to follow. Village artists are rarely remembered. Nor do they become famous enough to sell their art to the ruling market, for those who buy it only to show their appreciation for an antique or traditional culture. The exposure or knowledge of Indians towards their art has become limited in the way a foreigner arrives in India via Delhi or Mumbai and gets exposed only to the village art of Rajasthan or Maharashtra at the airport or urban cultural hubs. They are exposed to Bollywood cultural expressions and recognise/identify with movie-oriented behaviour, dance, music, clothing as Indian culture.

In the art and culture market also, urban artists draw attention first while rural artists hardly get recognition. City-based theatre artists or groups get access to administration and upper-class benefits, get space in mass-media, become research subjects for academicians etc. all of which are faraway dreams for the village artists. So indigenous artists of the land, who are in the villages have been taking a back seat and they get inferior complex in front of city-based artists.

Since the Covid-19 pandemic, many art and cultural events have moved their activities to the online space. From digital art exhibitions to various musical and dance performances, audiences have adapted to the confines of their screens, experiencing these from the comfort of their couch. On the face of it, theatre might seem like the easiest to adapt to the OTT platform, given the rising popularity of watching shows online. However, our theatre troupe Natya Chetana has consistently declined any invitation to perform our plays for a digital audience. The first, making the performance available in mobile or laptop is a suicidal attempt for art as audiences will gradually become too casual to receive the real spirit of a performance, which allow for gatherings and the creation of a sense of unity among audiences and artists alike. This two-way process will be broken, if the market of internet is allowed to mediate between the performer and audiences, resulting in a digital takeover of culture and art. At a time when buses are allowed to ply, ferrying 50 passengers and travelling through the night without any physical distancing, it is irrational to disallow performances gathering for 2 hours, with proper physical distancing.

Culture and art have been maintaining a balance between physical and mental health. Now during the corona period, suicides, psychiatric disorders, domestic violence, sexual harassment etc. are rising while the government is aiming only to protect the body, and not the mind. We must realise that life is not based on Loss and Benefit. It is not a profit-making business. Decentralisation of the market needs to be promoted, which will not only have an impact on the environment and all other species—by helping them live without turning natural resources into “money,” but also by allowing the market to become a humanitarian space that can be accommodated within financial deals, and uphold art and culture as a major driver of the society. Art can offer a spirit of cultural community, peaceful reflection on our needs and deeds, provoke a better choice of life and bring a balance between our physical and mental worlds. That is why theatre is not a commercial product to be sold in the market as a commodity. Rather, it is a dynamic ‘process’ among human beings while allows exchange of all kinds of power needed to live better.