We live in a world where the boundaries of our mind have extended beyond outdated social contexts and constructs. Human beings have become devices of sorts, whose affiliations to materials and other resources have take on a new socio-politico-technological nature. In such a world of fast-paced development, where basic human requirements of living have largely been taken care of (though at varying degrees), many people of middle socio-economic class have turned to question the very meaning and purpose of life. Increased demand for religious affiliations, spiritual groups, atheist collectives, and involvement in art forms to search for the self resonates with such a trend.

On the other hand, arise in the rate of childhood anxiety and depression, loneliness, suicide of young students and behavioural problems (violence and other forms of aggression) mirror the disruptions in family relationships, addiction to gadgets, problems in formal teaching/learning methods, and heightened multi-sensory stimulation from environment.

Individuals who seek rectifying apparatuses for such problems at the community-level often observe breaches in meeting these ends. At the same time, adversities against the young, women, transpeople, and the elderly are also increasing. They are more commonly victimised in organised crimes, sexual harassment, sex rackets, murders, and kidnapping in contemporary times. The data obtained in national surveys present an immediate demand for addressing these issues through an interdisciplinary method.

This is an alarming yet opportune circumstance for public health agencies in India, especially mental health services, to pause and rediscover their fundamental concepts and practices. The need here is to bring public and expert attention to traditional means of medicalising mental health and illness.

The Siri Cult, South Karnataka. Photo: Dr Baiju Gopal

Traditionally, public health networks have largely been localised in India. By deriving support from the people of a community, their knowledge as well as locally available resources, these networks have largely been successful in addressing and containing diseases at multiple levels. Such a decentralised approach to public health has also made services more accessible to populations, as they are not outside of the context and location of the community. These merits extend to public networks governing mental health as well, as they help move beyond stigmatisation and towards culturally relevant and effective practices.

The formation of a psychic system in any community unquestionably takes elements from existing shared beliefs, which also raises the need to similarly design the agents of change. Any agent of change can work on the psychic apparatus if it is related to the ethos it is developed in, while adapting it for a different culture would curb its relevance.

A cultural mix certainly bridges Eastern and Western contributions to mental health, but such an effort focuses more on the epistemological nuances of integration. For instance, epistemologies of an Eastern perspective put forward metaphysical and existential philosophies of human life while trying to understand the human mind and its processes, whereas Western psychotherapies reportedly note the need for inclusion of the individual’s psychological world.

The public health system in India has also seen a cultural influence, where one can see the power struggles between remnants of colonisation, and post-colonial cultural critiques. Medicalising the human mind in healthy and diseased forms by biomedical professionals took an upper hand and eventually silenced the culturally rooted indigenous and traditional healers here. Therefore, emergence of centralised mental asylums specialised in treating the mind and its disorders became popular and attempts to amalgamate this imported approach with that of native healing methods lost its practicality in due course.

Remarkably, Government of India constituted the Ministry of AYUSH (Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy) in 2014 to ensure the optimal development and propagation of these systems of health care(This was initially formed as the Department of Indian System of Medicine and Homeopathy (ISM&H) in 1995). AYUSH provides organised models of health in an attempt to equalise the availability of native healers in a culturally deprived healing scenario. Coexistence of these varied medical systems along with the ‘unorganised’ shamanic and mystic healing methods prevailing in India helps view mental health issues as psychosocial trauma and not limited to brain abnormalities.

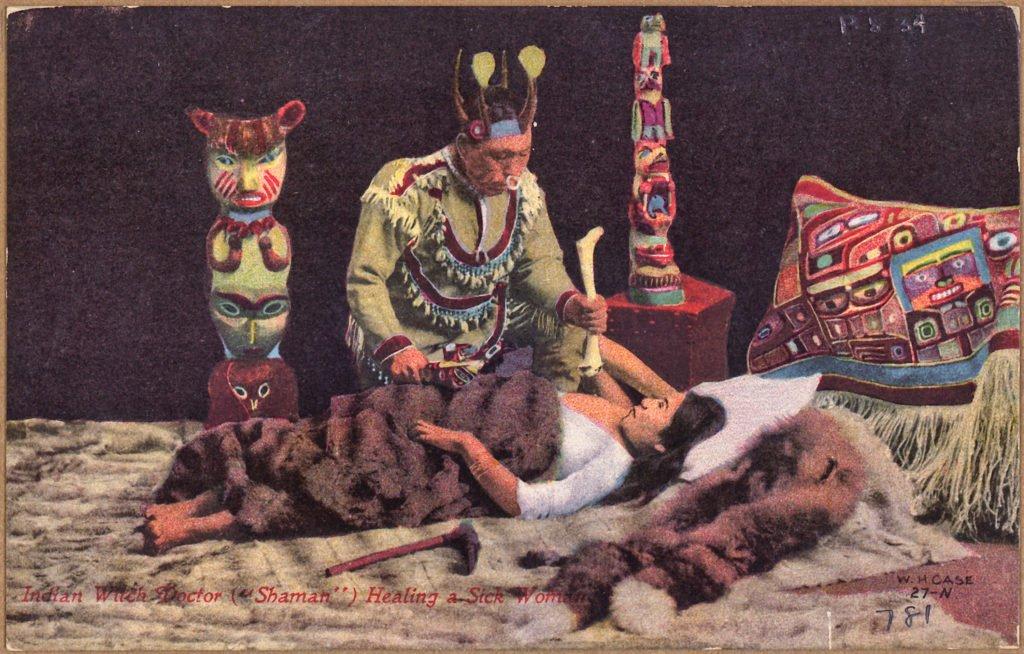

Color postcard of Indian witch doctor ( “shaman” ) healing a sick woman. Source: US National Archives and Records Administration

Healing takes different forms in religious places, rituals, and herbal medicines through the knowledge systems of mythologies, mediated by divine presence. The idea of healing here lies in an individual’s expression of subjectivity and the meaning that they attach to it. The world views of the healer and the client have identical linguistic traditions and the client is ‘predisposed’ to be healed there. These practices are significant in dealing with varied problems of individuals and communities with respect to specific cultural contexts.Even though indigenous knowledge systems are institutionalised and widely popular among local users, biomedicine has overruled and denied any position to them, criticising their ‘unscientific’ and ‘shamanic’ outlook.

Biomedicine, having taken on the role of being the regulatory discourse for public health in India, has set boundaries on the practice of and knowledge-sharing between all non-biomedical systems. Therefore, most of the indigenous systems appear to be marginal and legitimised in different settings. But it is interesting to observe that people widely seek out indigenous systems of healing outside the established governmental attitudes and regulations.It might have arisen from dissatisfaction with or failure of biomedical interventions, community acceptance and trust in a healer, financial constraints and/or better expression of their individual identity, etc. This is to say that practice of healers and people’s treatment choices in any community echo a complex psycho-historical interplay of political, economic and socio-cultural dimensions.

Moreover, one can also observe renewal in the existing systems of the theory, research and practice in mental health disciplines. Emerging research studies and books in community psychiatry, cross-cultural psychiatry and multicultural counselling witness epistemological gaps being addressed very early in the development of knowledge systems. These developments explore the inner world of the clients and their community through process-oriented approaches, and acknowledge subjective theories of illness. Development and expression of an individual’s subjectivity refers to psycho-social intertwining of power and meaning making.A paradigm shift is marked here in addressing the issue of mental health through philosophies of subject-and-object-dichotomy, and mental health professionals resort to empathetic means of getting to know the person in need.

Training and research of mental health agencies in terms of prerequisites for variations in human psyche in its developmental stages, while moving ahead in specific psycho-cultural space, would revise and update the treatment modalities. Revitalising and reintegrating indigenous systems of medicine as ‘ethno-medicine’ (Sujatha & Abraham, 2012) also brings in values of trust, love, peace and harmony into psychotherapy for sustaining life.Uplifting the psycho-social face of therapeutic approach and therefore, personalising it grounded in its cultural space would propose a new global perspective on mental health and its governance via public health systems.In order to do this, we need to incorporate the research and studies on the Indian native systems into mental health curricula at universities, as well as in public practice, in a way that is both deeply nuanced and understanding of these systems, as well as cautious of not letting ill practices enter the field. Further research into the methods of such an in corporation is highly recommended.

References

- Cornelissen, R.M., Misra, G & Varma, S. (2014). Foundations and applications of Indian Psychology: Pearson.

- Rao, K. R., Paranjpe, A. C., Dalal, A. K. (2008). Handbook of Indian Psychology. New Delhi: Foundation Books.

- Sujatha, V & Abraham, L. (2012). Medical Pluralism in Contemporary India. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan.

- Thomas, T.M., Gopal, B & Sasidharan, T.(2018). ‘Towards a Culturally-Informed Counselling and Psychotherapy’ in Mishra, G. (eds.) (2018) Psychosocial Interventions for Health and Well-Being. Springer.