“In an age of acceleration, nothing can be more exhilarating than going slow. In an age of distraction, nothing is so luxurious as paying attention. And in an age of constant movement, nothing is so urgent as sitting still.”[1]

In the day-to-day life of any individual, the body is special and sacred. It is the site of furious activity; it is the location where a host of forces collide or relate, struggle for domination or are unified. The state, the market and we ourselves, either as military or civil subjects, individuals or groups, are continuously developing an arsenal of methods, strategies and technologies to govern, exploit, enhance and mould our bodies.[2]

When I was younger and intense, I aggressively attempted to assert my will and control what the body was trying to do. At the peak of fitness, due to years of training and discipline, in peace and in combat situations, the body was at its optimal state of awareness and readiness; comparable to the intuitive, instinctual state of an animal in the wild; ready to respond to any stimulus in the environment, “when the Body had become all eyes”[3].

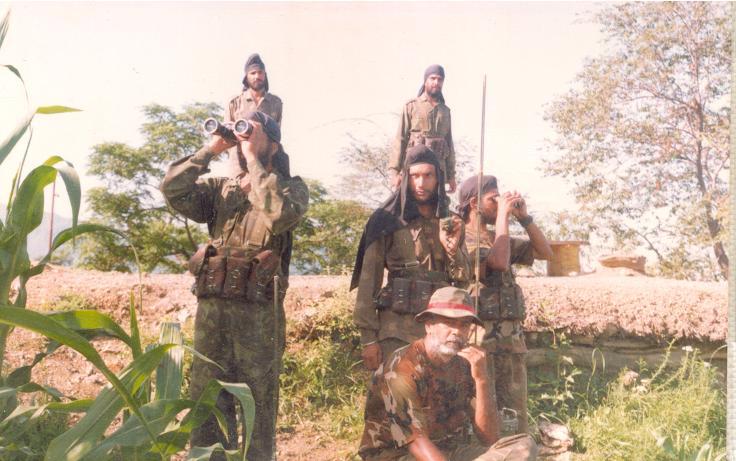

Col. Santhanam and his men, keeping vigil.

Now things have calmed down, and there is a sensitivity to the body and the breath. With the right practice and awareness, I got to understand the relationship of the body and the mind and once this understanding dawned, my relationship with my body (and mind) changed, and, my reflections on the interconnections of the body and the self began to grow.

In combat situations, unlike the popular depiction of ‘action’ in comics and movies, it is mostly ‘stillness’ that prevails. Hours and hours of walking and searching in the jungles and then, suddenly, a sharp burst of gunfire and then eerie silence again, as the bodies are counted and the injured are attended to. A soldier sits in ambush day in and day out, waiting for the ‘quarry’ to walk into the killing area. A good soldier learns to ‘sit still with an active mind’ very early in his life in the armed force.

As a soldier grows older, having lived a life of so many contradictions, he continues to ‘sit still with an active mind’. In an attitude of acceptance and vigilance at once. Some people confuse acceptance with apathy, but there is a world of difference between the two. Apathy fails to distinguish between what can and what cannot be helped; acceptance makes that distinction. Apathy paralyses the will-to-action; acceptance frees it by relieving it of impossible burdens.

Arguably, all of us have two egos, two selves.[4] These parallel and distinguishable identities make up who we are and profoundly affect how we behave. One is our subjectivity, including our proprioceptive sense of the relative position of our body parts as well as the strength of effort being employed in movements. The other is our sense of our reputation, a reflection of ourselves that constitutes our social identity and makes how we see ourselves as integral to our self-awareness. The relation between how we appear and who we really are is highly complex and ambivalent.

This second ego (what we think others think of us, or sometimes even what we would like to imagine that others think of us) is woven over time with multiple strands, incorporating how we think people around us perceive and judge us. In fact, our understanding of this second self is not created simply by reflection, but rather by the refraction of our image that is warped, amplified, redacted, and multiplied in the eyes of the others. This social self controls our lives to a surprising extent and it even drives us to commit extreme acts. [5]

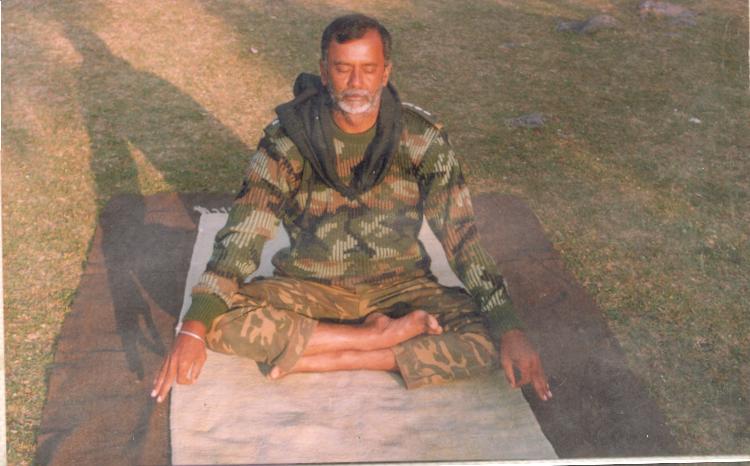

The writer, when he was a Commanding Officer. He is a veteran of the Sikh Regiment of the Indian Army

Generally, what shape and fashion these two egos are two aspects of rationality: internal consistency of our decisions and maximisation of interests. According to utilitarian economists and evolutionary theorists, the two go together, naturally and necessarily. But then, there are some who can be rational and coherent when it comes to their pursuits, and wholly disinterested in any personal awards. Researchers analysing people with such altruistic bend have found that multiple mechanisms come into play when we are defending our self-understanding or self-image: the need to demonstrate character (izzat)[6], concern for morality, the continuity of our identity, and the feeling of belonging to a community or a tradition even if it is only imaginary.[7]

A fairly large proportion of soldiers could fall into the latter category, as they belong to small and closely knit units and regiments, with old traditions and ethos. They are ordinary people who consistently perform ‘unordinary’ acts of courage and heroism. So, their attitude towards life in general, and their personal wellbeing in particular, can be different from that of others. I would concede that anybody in any walk of life can have the attitude of a soldier – a warrior.

So, what is this attitude that makes a soldier or a warrior ‘different’?

The attitude of a warrior is one of respect and discipline, for he knows that there is no absolute security to his life. His training and knowledge have taught him to respect his adversary, to respect the unknown and the unexpected. He knows that it is his discipline and training that will increase his odds of survival when pitted against the reality of security, ‘which is almost mathematical, based on the probability of different risks and the effectiveness of different countermeasures. He also knows that security is just a feeling, based on his psychological reactions to both the risks and the countermeasures’. [8] You can be secure even though you don’t feel secure, and you can feel secure even though you are not really secure. A good soldier knows and accepts this paradox.

Now when I am older and much wiser, I see that my body has instinctually become ‘cultivated’ to engage the present in the moment, in a state of heightened awareness. I realise that this has come about primarily due to understanding the real meaning of courage, discipline and responsibility. The dictionary meaning of courage is – “That quality of mind which enables one to encounter danger and difficulties with firmness, or without fear, or fainting of heart; valour; boldness; resolution.”[9] Acceptably, fearlessness is a synonym of courage. Thus, one not uncommon school of thought about courage in our culture is that it relates to the absence of fear. But from my experience I have learnt that courage is the quality of mind or spirit that enables a person to face difficulty, danger, pain, etc., in spite of anxiety or fear. In combat situations it is physical courage and in peace it is moral courage that comes to the foreground.

The writer in meditation during his army time

For any degree of consistency in courage, you need to have two things – Discipline and Responsibility. Discipline, not as in “the practice of training people to obey rules or a code of behaviour, using punishment to correct disobedience.”[10] But, discipline, as in the attitude to learn. Discipline, as it comes from the root ‘disciple’—one who wants to learn. [11]

And, responsibility, not as in “the state or fact of having a duty to deal with something or of having control over someone, or the state or fact of being accountable or to blame for something.”[12] Responsibility, as in a combination of response and ability. An attitude of learning that leads to knowledge, to skill sets, and that which gives one the ability to respond to any given situation or challenge – appropriately and efficiently. The ability to respond adequately and competently to a variety of situations is what makes one a responsible person.

Courage is built on this bedrock of discipline and response-ability. Living a soldier’s life offers a continuous challenge to nurture and effectively develop one’s intellectual and physical capacities, to identify one’s potential, to be the best possible version of oneself. Here’s a poem which used to be on my table or on my board through my army career:

The old woman’s shoulders

were dry, unfleshed,

with outstanding veins;

her low belly

was like a lily pad.

When people said

her son had taken fright,

had turned his back on battle

and died,

she raged

and shouted,

“If he really broke down and fled

from the thick of strife,

I’ll slash these breasts

that gave him suck,”

and went there

sword in hand.

Turning over body after fallen body,

she rummaged through the blood-red field

till she found her son,

cut, in four pieces,

and she rejoiced, this day

more than on the day

she gave him birth.[13]

Over the years, as a soldier I have learned to confront and accept the many paradoxes that I must survive, accepting responsibility and still be able to live with myself with ‘grace under pressure’.[14]

“Courage is the most important of the virtues, because without courage you can’t practice any other virtue consistently. You can practice any virtue erratically, but nothing consistently without courage.” [15]

Image credits: Santhanam Archives

[1] Pico Iyer

[2] The Body is a Battlefield – Philippine Hoegen

[3] When the Body becomes All Eyes – Phillip B Zarrilli

[4] Mamakar means how I think of myself, the self-image I hold to be true. Ahamkar means how I project myself for the world to see.)

[5] Reputation – Gloria Origgi

[6] Izzat – honour, reputation, or prestige.

[7] ibid – Gloria Origgi

[8] In the essay ‘In Praise of Security Theatre’ – Bruce Schneier

[9] Oxford English Dictionary.

[10] Oxford English Dictionary.

[11] Living Tao – Osho

[12] Oxford English Dictionary.

[13] From Purananuru, The Four Hundred Songs of War and Wisdom: An Anthology of Poems from Classical Tamil

translated and edited by George L. Hart and Hank Heifetz.

New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

[14] Ernest Hemingway

[15] Maya Angelou