10 October 2014Last month, on this day, internet browers across the world displayed the proverbial ‘spinning wheel of death’ on thousands of major websites. This emblem appeared as a common-sensical reference, an unambiguous meaning. For the Battle for the Net initiative, this Internet Slowdown Day was meant to warn that any hint of a cyclical time would cause legitimate frustration to our (linear) living and working spaces. While the underlying corporate lobby remains to be confronted and resisted – American telecommunication companies planning to reserve the fastest broadband connections only for top firms – one would not miss that such a tension is exclusive to a particular type of access. We congratulate ourselves for having created the internet, a splendid pathway for a humanity engaging in speed. But, indeed, the democratisation of media and knowledge has given rise to the impression that speed, and therefore time, are commodities accessed through external agencies. While technology’s presence in the world seems ubiquituous, we may forget the extent and depth of cultural heterogeneity, rendering even actual access ineffectual. If the internet is increasingly a component of and for a global world, how can such local challenges be transcended to contribute to a levelling of inter-connected development? This week, P P Sneha explores the possibilities of redefining the idea of access through the channels of education and learning. Hari Shankar Prasad searches our intellectual history to find in the process philosophy of Buddhism the possibility of undertaking an internal journey where one can do more than just stare at time’s cruel wheel. Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations. |

||||||||||||

Rethinking Conditions of AccessP P Sneha |

Processes of TimeHari Shankar Prasad |

|||||||||||

Requested file could not be found (error code 404). Verify the file URL specified in the shortcode. |

Listen |

Listen |

Requested file could not be found (error code 404). Verify the file URL specified in the shortcode. |

|||||||||

|

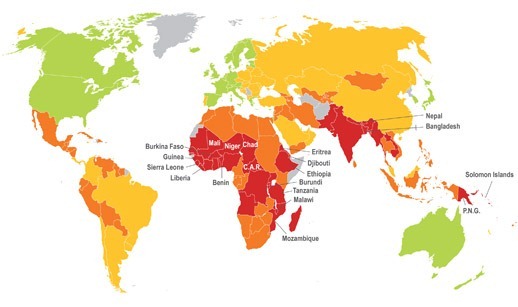

The advent and pervasive growth of the internet and digital technologies in the last couple of decades have caused several changes in the way we now imagine education and processes of learning, both within and outside the classroom. The increasing use of digital tools, platforms and methods in classroom pedagogy, and the access for students to resources through online and collaborative repositories such as Wikipedia have led to a change in not just teaching practices, but also in the learning environment, which has now become more open, iterative and participatory in nature. While increased access to the internet may be one factor contributing to this change, the conditions of such access – how it is made available, to whom and for what purpose – still remain contentious. As per recent statistics, India has more than 200 million internet users, but as several studies on online users have illustrated, the numbers are hardly indicative of the nature of online engagement. The problem of the ‘digital divide’, though much debated and addressed, still persists in India, as in several other countries, with lack of infrastructure and low broadband speed being two among several reasons for the slow move in bridging this gap. Last year, the Digital Inclusion Index map The problem of the digital divide itself has largely been understood as one of access to the internet and/or broadly digital technologies, but the conditions of this access, in terms of the nature of its use and adaptability to a dynamic and ever-changing technological landscape is something that needs to be looked at critically, in order to provide a more nuanced understanding of the problem itself, and its inherent conflicts. The technological landscape we inhabit today is quite diverse, and rather multi-layered, as a result of which conditions of access also differ across spaces and in degrees. The problematisation, therefore, will need to be more qualitative and nuanced, to take into account several variables spread over social, cultural and economic categories.

The assumption of the internet, as an open and accessible, therefore neutral space, has also been questioned time and again, with the latest debates around net neutrality being illustrative of this conflict. Though there is a growing interest in exploring and using the democratic potential that the internet offers, as demonstrated by several forms of online social activism and the growth of open access digital knowledge repositories and public archival spaces, there are also pertinent concerns about privacy, accessibility and the quality of online interaction and content. A large part of this uncertainty and the conflicts we see around access and regulation may be attributed to the fact that the nature of the internet, or the digital itself as concept, method or space has not been adequately explored or theorised. As a public sphere, it often reprises certain systemic forms of injustice and marginalisation seen offline, and conflates them with notions pertaining to the personal. As such, social, economic and linguistic barriers mediate the access we have to certain kinds and forms of discourse online, thereby making physical access the first step towards being part of the labyrinthian world that is the internet. How can e-learning start, These conflicts are present in the classroom and other spaces and processes of learning as well, where traditionally there has been resistance to the use of technology, and particularly the internet as it is seen as a disturbance or a deterrent to learning. But technology has always been a part of the classroom, and now with the mobile phone becoming ubiquitous, it is indeed difficult to imagine that a student who has access to such a device would be disconnected from the internet, or not look toward other digital tools and methods to engage with, for educational or recreational purposes. However, indeed, how much of this engagement is effectively connected to learning is still a bone of contention, and is yet to be explored adequately.

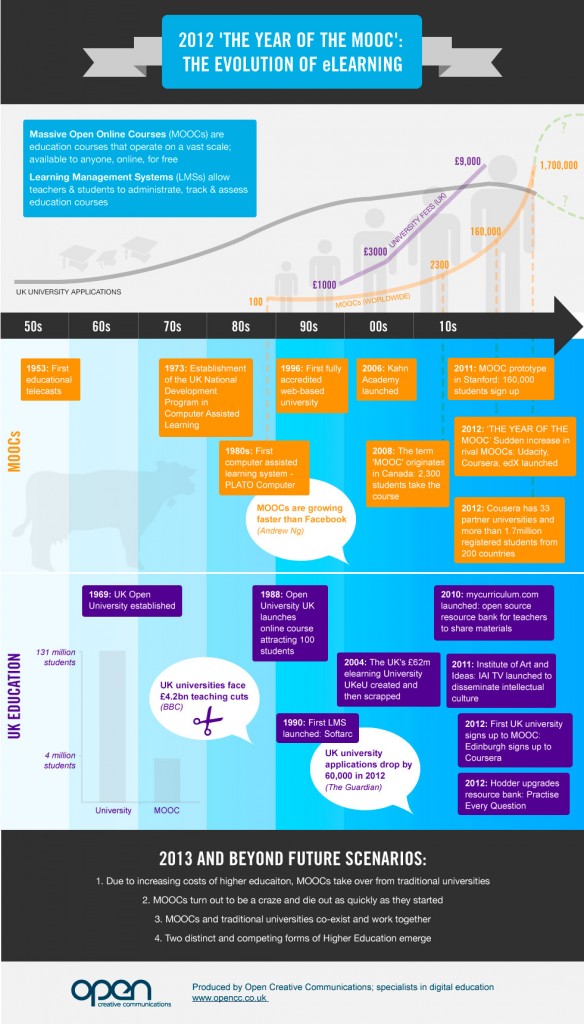

What are the changes in the learning environment that the advent of digital technologies has produced? What challenges do they pose for both teachers and students? And what are the possible solutions that these areas of research are opening up? A more integrated and inclusive approach in designing methods and tools for use in the classroom could be one way of making issues and conflicts in this space more transparent. Several efforts in education technology and experiments in digital learning have focused precisely on this aspect. The sheer visibility and vastness of the internet offers several possibilities in terms of access to materials, tools and resources online. Several large-scale efforts in digitisation made by both the state and public organisations are attempts to utilise this potential, and they speak of the growing interest in making material available online for both classroom teaching and research. The MOOCs are slowly challenging the universities The growth of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) is an example of the fervour of online platforms of learning, which provide students across the world with an access to teaching and course material from some of the best institutions. However, there have been, at least in their earlier versions, several critiques of these platforms, as well, precisely because they replicate a certain classroom teaching model that is not accessible to students everywhere. This urges us to revisit the premise of such structures. The ‘digital turn’ in the last couple of decades has engendered several changes in the way knowledge is now produced, disseminated and consumed by people located in different areas. It has also created a need to constantly rethink existing systems of learning we have in place, to plug the gaps that develop between people, skills and resources. It is only through more attempts to problematise the notion of access qualitatively, and to better understand the role of digital technologies and the internet in terms of changes in learning environments, that we may be able to understand and utilise its potential to the best. |

Ever-increasing desire for materialistic pleasure, endless consumption, innumerable choices without commitment… These paradoxes are familiar – our excesses of speed, and yet our need for it, appear as the source of our suffering today. Various Indian traditions elaborated, millennia ago, worldviews and solutions that would remain relevant across centuries, and even under such historical changes. The Buddhists, for instance, will say that the need to satisfy desires – speed being one instance or one aspect of a desire – is the result of un-awakened mind and wrong value preferences. The birth of Buddhism lies in the Buddha’s Awakening, consisting in the intuitive realisation of the universal principle of dependent co-arising (paticcasamuppada), which defines a process view of reality, both physical and mental. According to it, a thing is not a static but a dynamic entity, which means it is a process of temporally-ordered occurrences of events. In process philosophy, time is temporality, intrinsic to the successive occurrences, characterising the passage of time as asymmetric and transitive. The Buddhist process philosophy presents an adequate account of a wide range of issues concerning ontology, epistemology, ethics, and philosophy of mind. It is combined with a phenomenologically informed perspective. The present article develops itself within this framework. The Jatakas constitute a classical book for the Buddhists, where earlier lives of the Buddha are retold. One of the Jataka stories has a remarkable narrative, on us human beings, and the way we understand and live with time. Time (kala) eats all beings, along with itself,

But the one who eats time cooks the cooker [sic] of beings. The American scholar Steven Collins quotes the classical commentary on the Buddhist Jataka view of time, which is very similar to the one in the Atharvaveda. Time is indeed presented as a monstrous character, but in a different sense: ‘Time’ refers to such things as the morning and midday meals. ‘Beings’ here means living beings; time does not (actually) consume beings by tearing off their skin and flesh, but it is said to ‘eat’ and ‘consume’ them by wasting away their life, beauty and strength, crushing their youth, and destroying their health … It leaves nothing, but eats everything, not only being but also itself; (that is to say) the time of the morning meal does not reach the time of the midday meal, and likewise with the time of the midday meal (and what follows). ‘The one who eats time’ is a name for the Enlightened person, for he wastes away and eats the time of rebirth in the future by the Noble Path … ‘Cooks the cooker of beings’ (means): he has cooked the craving which cooks being in hell, burnt it and reduced it to ashes.

Intentional deeds feed one’s karma in the Buddhist wheel of time This passage clearly paints the image of the inexorable temporal destiny of an unenlightened human being whose unwholesome karmas are responsible for his miseries here and hereafter. But the great hope is that he can reverse it by following the Buddhist path, which is a path of mental purity from the defilements of craving and ethical conduct. And this path ultimately ends in the dissolution of his temporality itself. This means that a Noble Person can destroy his suffering by destroying his craving, which is the real Time Monster for him.

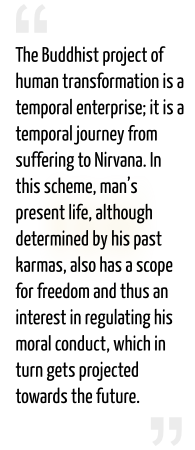

Buddhism recognises the central position of man in the society and the world in which he is born and lives. He can transform his destiny through his own transformation in terms of awakening and virtuous ethical conduct, which can be equated with Nirvana, i.e. freedom from perpetual suffering. But this involves temporal stages in its development: the transcendence of time requires itself a temporal process. Ethical conduct is not confined just to intersubjective relations; it is meritorious or non-meritorious as per the quality of each ethical action – whether it has good or bad consequences for society and the world as a whole. The Buddhist project of human transformation is a temporal enterprise; it is a temporal journey from suffering to Nirvana. In this scheme, man’s present life, although determined by his past karmas, also has a scope for freedom and thus an interest in regulating his moral conduct, which in turn gets projected towards the future. This temporal journey is the journey of the dynamic consciousness or mind, which is fuelled and perpetuated by the intentional ethical karmas. In essence, human life is a temporal life. And it is because our temporality is something we can actually affect, that ethics becomes the first philosophy for Buddhism. The Buddhist effort to eradicate suffering and enter a-temporal Nirvana is the spinal cord of this tradition since its beginning, but each generation of practitioners and scholars has attempted to design new ways to actually undertake that path. This also implies slight modifications in the way the problem is understood. With the fourth century commentator Vasubandhu, for instance, the focus turns to manana or reflective consciousness – the idea that one layer of our awareness is always present behind each of our actions, thoughts and modes of being. Vasubandhu, who belongs to the sub-tradition of the Yogacarins (very influential on Mahayana Buddhism, including Zen), is thus bringing what is known in western philosophy as a ‘phenomenological’ outlook on time – an analysis of time through its everyday, subjective experience, instead of a larger, metaphysical discourse about it. Vasubandhu, in a classical Chinese representation

Our phenomenological time-consciousness constructs both (i) temporality, following the flow of successive eventual awarenesses, which are forms of consciousness, from past to future via present, and (ii) enduring or extended time, which are falsely taken by dogmatic metaphysicians as an independent substantial time. In either case, the experience of time is essential to a rapidly changing consciousness. And, indeed, the idea of an eternal and external time is for all the Buddhist traditions an illusion: none of these schools accepts consciousness or time, or for that matter any other thing, as an invariable, static, unchanging, independent, and enduring substantial reality. And this shift is further operated with Vasubandhu’s school: there is a clear shift of focus from ‘ontology of time’ (time in its essence) to ‘epistemology of time’ (time as we get to know about it) and finally to ‘phenomenology of time’ (time as we experience it). The Newtonian time, unquestionable in its external, absolute reality, is thus far beyond us: the human can access and question time, because time is as such a matter of internal experience. Based on this understanding, the Buddhist traditions have laid the ground for spiritual paths around certain specific practices. The intense, introspective meditation of the Yogacarins, for instance, is an attempt to appease and purify the afflictive mind’s illusory superimposition of spatio-temporal objectivity, and our attachment to it, so to attain a consummate state of the stream of consciousness, and ultimately Nirvana. In Buddhism, purification and spiritual development of mind are the basic requirements to overcoming the temporality of one’s suffering life and attaining a-temporality of peace – Nirvana. But that is a long process, so… no rush! |

|||||||||||

|

P.P. Sneha works with the Researchers at Work (RAW) programme at the Centre for Internet and Society, Bangalore. She has a Master’s degree in English, and has previously worked in the area of higher education. This essay is a reflection on some of the learnings from projects on the quality of access to higher education and a mapping of the digital landscape and the growth of Digital Humanities in India, conducted by the Higher Education Innovation and Research Applications (HEIRA) programme at the Centre for the Study of Culture and Society (with support from the Ford Foundation), and the CIS.

|

Hari Shankar Prasad is Professor and Head of the Department of Philosophy, University of Delhi. Through a research career of nearly three decades, he has worked on Indian metaphysics, and specialised in the questions of epistemology, philosophy of language, ethics and time in Buddhist philosophy. He is the author of several monographs, including Essays on Time in Buddhism (Indian Books Centre, 1992), Time in Indian Philosophy (ibid., 2992) and The Centrality of Ethics in Buddhism (Motilal Banarsidass, 2007), as well as numerous academic articles.

|

|||||||||||

Disclaimers: The opinions expressed by the writers are their own. They do not represent their institutions’ view.

LILA Inter-actions will not be responsible for the views presented.

The images and the videos used are only intended to provide multiple perspectives on the fields under discussion.

Images and videos courtesy: GK & Vikki Hart | Digital Divide | Next Big What | Open CC | Ahermin | FPMT

Voice courtesy: Samuel Buchoul

Share this debate… |

… follow LILA… |

||||