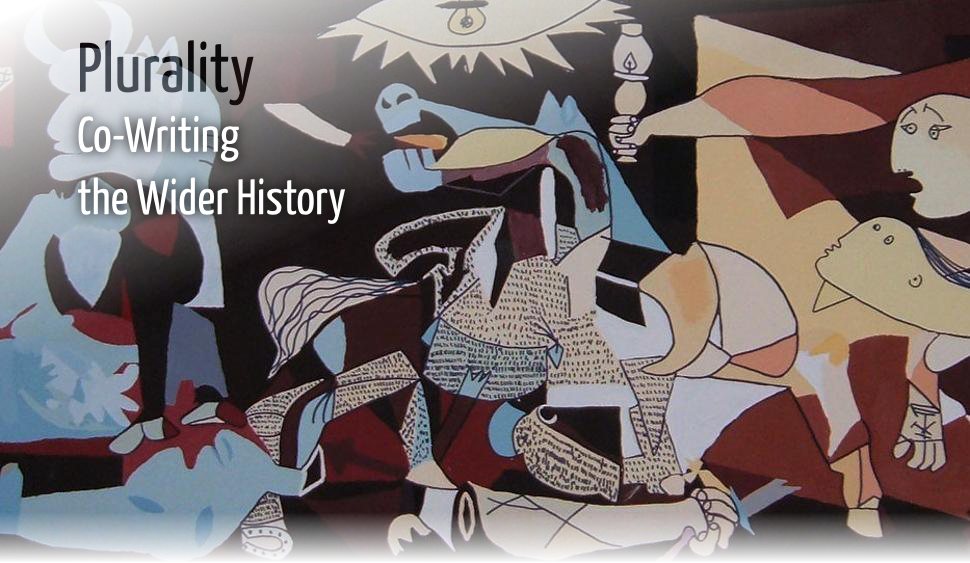

3 March 2014“Identities are the names we give to the different ways we are positioned by, and position ourselves within, the narratives of the past.” Stuart Hall shall continue to illumine our debates on multiculturalism. Even as the latest communication technologies forge a brave new village from the ruins of our metropolitan cities, there are screams that return to us the monochromatic beast of culture, scaring away the splendorous multiplicity of human histories and fragmenting their intermingling tonalities. Are the recent instances of censorship and discursive atrocities launched on democracy the proofs of the mirage of our cosmopolitan utopia, our coloured Guernica? This week, LILA Inter-actions goes international to examine the many complex relations we have shared with time. Pepita Seth offers us hope, drawing from over four decades of her cultural exploration in Kerala, and celebrates the country’s pluralism. Eddin Khoo travels through the “multi-culti” hurdles across the globe and in his native Malaysia to reassert the position of each individual at the heart of her history. |

Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations and descriptions.

One Mirroring the OtherPepita Seth |

The Multicultural FetishEddin Khoo |

|

The ‘personal’ here is not necessarily universal but in the present climate, of marginalising (and worse) the ‘other’, perhaps, a slight balance should be introduced by describing my experiences since they have never caused me to consider myself as ‘the other’. And, to face matters clearly, I do not ascribe this to being white. Kazchaseeveli: The morning procession at Guruvayur temple, For forty plus years, India, specifically Kerala, has been overwhelmingly generous to me. People like me—British, female, foreign—are not supposed to enter Kerala’s temples and should not even dream of doing so at Guruvayur. Yet, in 1981, I was allowed in, and officially so. This permission changed and enriched my life, largely because what I found on the inside of this supposed bastion of impenetrable, access-denied orthodoxy was a genuine delight about the fact that I was there and that I was welcome. Last week, after having been away for many months, I came back to spend 24 hours in Guruvayur, and it was truly humbling—handfuls of prasadam, even offers of darshan, smiles, hand taken, queries made, friendships re-established. I left the temple feeling surrounded by a kind of glow, and smiling ruefully from the guilt I felt at not being able to attend this year’s Utsavam.

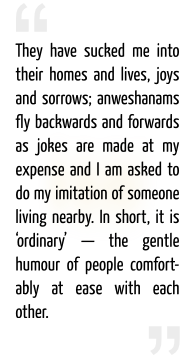

Ironically though, I was returning to another part of Kerala, Malabar, to resume my ongoing work on Theyyam. Returning to people whose affection and support are almost overwhelming, particularly in view of the outside assumption that this cannot possibly be the case. Yes, I have known many of them for 30 years. Small boys, some still unborn when I met their parents, are now performers. They have sucked me into their homes and lives, joys and sorrows; anweshanams fly backwards and forwards as jokes are made at my expense and I am asked to do my imitation of someone living nearby. In short, it is ‘ordinary’—the gentle humour of people comfortably at ease with each other. In this vein thoughts come—of the experiences, small incidents, that I have had. One, years ago, was in Chennai at an exhibition of my photographs of Kerala’s rituals, when an old Nair lady and, I assume, her grand-daughter, meticulously examined every image, once or twice recognising those photographed. When she reached me, she smiled and said: ‘How you love us!’ Just four words—words I can never forget, for, what she said was completely true, largely, to my mind, because they have given me so much love. Another incident happened two years ago when, to my utter surprise, I was awarded the Padma Shri. Among my many reactions was my delight at being listed as Pepita Seth, Kerala. In fact when, sometime later, I was asked what recognition I was getting in the UK, I said, ‘how were they to know about it, where did any of you mention I was not from Kerala?!’ When I went to Guruvayur after the announcement of the award, it was like moving through a sea of happiness. A ritual artist told me that this was the first such award for Guruvayurappan, and for someone from Guruvayur! For them, it was like a member of the family getting the award. Not untrue, when I consider all those who have, over the decades, done so much to help me. I pause here, and look at what I have just written, wondering if it is not all too small and, well, trite, given the contemporary developments. But, at the same time I focus on what sometimes eddies about me, when I meet the odd foreign scholar or academic who works on Indian subjects. It is now not uncommon that I am asked if I find I am discriminated against, if I feel my ‘knowledge (!?)’ is unwanted, indeed that I am unwanted. Even as my answer is a resounding ‘no, absolutely not’, I tend to reflect on how these questions are worded. They seem to come, at least subconsciously, from a sense that they know better. There is an undercurrent of resentment that India is now producing her own scholars and specialists and, suddenly, they are, or believe themselves to be, sidelined. But there is also a disconnect. For instance, to my absolute horror, and some distress, a scholar once described me as someone who advises Guruvayur’s priests on their rituals! Initially I thought he was joking, but no, he genuinely thought it was what I did. This seems to show a considerable degree of ignorance about what is possible in this space, and what is absolutely inconceivable. I cannot but wonder how someone ‘familiar’ with India can have such an idea. And, all too often, the same level of ignorance and insensitivity is seen in Theyyam shrines where photographs are taken with no respect, regard or even concern for the values upheld in those spaces. Instead there is an attitude of ‘so what’, ‘it’s a show, an entertainment’; the concept that they have entered a locality’s place of worship is largely non-existent. Yet against such experiences I can balance what happened last night when a young Theyyam performer arrived with his wife and child, beaming and laughing. He had come to tell me that for the first time he was going to perform an important Bhagavathi and wanted to invite me. The curiosity of the neighbours meant he had to explain that he’d known me as a child and that I’d specially photographed his family and always gave him photographs of his Theyyams. It’s a small incident but it touched me deeply even as, on a wider scale, it shows what is so generous about this country.

But, of course, I again wonder at the slightness of my stories when played out alongside events that make one’s blood run cold. The horrors that assault us on a daily basis, the incidents of violence against particular races, identities, and cultures; the censorship and suppression of minority voices, the slights and sneers that one’s conscience cannot even consider evading. That, worst of all, things seem to be escalating. If individuals can so generously induct someone like me into their lives, why can’t a wider public do the same: see the stranger, the other as a mirror image of oneself and so find a common ground? In northern Malabar there is a Theyyam deity, Kshetrapalan, the guardian of temples, who once demolished a semi-ruined shrine and built a mosque to give a growing community of Muslims a place of worship. This, in essence is a sharing of cultures and spaces, even as the other is respected. This fineness shows India’s profoundly pluralistic dimension. It is beyond me to suggest what can be done, political will being what it is. The great hope is that our children can, at an early age, be shown what is common to us all, that with opened minds they come to recognise that this will give them a share of the wider whole. As India is railed against for the dreadful things that now too often happen, it can help to recognise that the other side of the coin exists. And that I have been lucky to experience it. There are a few absolute essentials in, as it were, entering another culture: a sense of humour and a willingness to see oneself as occasionally ridiculous and to totally suspend any comparisons with anywhere else. The bottom line is that if the locals live quite contently in their way it is obvious that one can, too. One’s willingness to know about them is perceived well, and doors start opening. Yes, there are hiccups and problems but, to me, there is no doubt at all that the rewards are worth everything. |

Perverse, true, but also perversely pleasing to conjure up the image of one who consistently invokes harried and severe responses from the politically correct to anything he says by often – though not always – simply getting it right. Almost two decades on following the experiment that was ‘Cool Britannia’, David Cameron, the present leader of Britain, in his maiden speech as Prime Minister, duly pronounced the failure of “state multiculturalism,” paradoxically provoking a much needed debate on the contours and viability of the concept. In the wake of 911 and 77; the Burqa and Hijab controversies; the stabbing of Theo Van Gogh in open daylight on the streets of ‘liberal’ Amsterdam; the loud, insidiously state-supported, rebellion against liberal values, often deliberately portrayed as inextricably bound to such ‘dangerous and infectious’ ideas as liberalism and pluralism and as essentially promoting, “homosexuality, lesbianism, bisexuality and transsexualism,” in such diverse and polyglot, albeit increasingly puritanical societies as ‘moderate Malaysia’; the rise of various orthodoxies of the religious right; the accentuation of morality politics… In all that, little, it can be said, has been proffered to counter initial doubters of the multiculturalism experiment, such as A. Sivanandan, as being little more than a concession to the promotion of “saris, samosas and steel bands.”

Apart from the act to scuttle and search, in these desperate times, for such complimentary terms as ‘cosmopolitanism’ and ‘pluralism’ to serve as further constructions for the “multi-culti,” it is becoming increasingly evident that the struggle to make sense of cultural diversity rests essentially in the inability of contemporary societies to grapple with that ‘art of containing multitudes’ and discovering the necessary balancing act to forging a legitimate political community while navigating individual rights and specific community interests.   It has also been proved that the multiculturalism debate has fallen into the snare of an all-too-gestural, purposeless argument over terms in a time defined principally by an impoverishment of terms, an all-too-glib wrestling over the vagaries of identity politics and its legalisms, even as it is becoming ever more manifest that one of the principal limitations of the law is its inability to grapple with contradictory contentions. There has been no time more fitting than this, perhaps, to invoke dear Mr. Bumble’s verdict: “the law is a ass… a idiot.” It might not be all too smug to remark that it would all come to this in the first place. Since the very concept of ‘multiculturalism’ had to be rooted in the notion of culture, why was there so little by way of concession, reference even, to that great beast ‘history’ – the veritable shaper of culture, either left forgotten, hobbling and cast as irrelevant on the stage of multicultural delusions, or beaten into shape, made malleable and devoured by the unfolding drama of nationalism? Cultural crossings: Kalidasa’s Shakuntala was sketched as a ballet by Sufi Hazrat Inayat Khan in 1914. Modern Dance group of Alexander Shishkin staged the sketch in 2002 at Scriabin Museum, Moscow. In Southeast Asia, all too long perceived, with a wave of the proverbial hand of academia, as little more than, ‘greater India’ or merely an emporium of people, places and things with ‘no real culture to speak of’, the undulating of the multiculturalism debate has proved especially perfidious. A region innately bastardized and heterogeneous, forged by the historical confluences of disparate cultural and religious influences throughout its history, the principal challenge to navigating culture since the commencement of the post-colonial epoch in the region has been the practice of managing it according to the dictates and exigencies of the nation-state. A bureaucratized culture, complimented by the weight of largely authoritarian state systems within the region will inevitably induce cultural fissures and the experience of maturing to democracy for the Southeast Asian region has been one fraught, principally, with implosions brought about by a clash of cultures and a history of cultural essentialising. The processes of the construction of history to serve nationalist ends have resulted in culture being either wielded towards a rhetorical basis for hegemony, pitched to assert the perceived victimization of one over the other or simply tokenized for purposes of tourism and commerce— all, efforts to, in the words of the historian Farish Noor, “toy with history again.” Another increasingly strident dimension comes from the utopian calls for the re-envisioning of a society bereft of historical foundations. Within island Southeast, in Malaysia and Indonesia principally, Islamist calls for the implementation of religious law have been accompanied by very real efforts at obliterating an institutional memory. In the northeastern state of Kelantan, governed since 1990 by the Islamic Party of Malaysia (PAS), forms of traditional, ritual theatre – the stuff of a living history replete with complex historical interactions – have been summarily proscribed since the emergence of that party in that state. Wayang Kulit, Malaysian shadow puppetry from Kelantan The predictable list of acts of banning – the practice of delineating clear boundaries between the halal (permitted) and the haram (prohibited) aimed at books, forms of cultural practice, but principally, at a memory and imagination defined by plurality, have served as the foremost challenge to perceiving culture in all its expansiveness and complexity.

If the barbarians, with their proverbial book burnings and appeals to the tribe, are no longer only lingering at the gates but have already shattered the walls and seized the fortress of common sense, a resistance rooted in delusions of gestural notions of multicultural niceties, and appeals to our perceived ‘civilized’ humanism is not only bound to hopelessly fail, it is surely not going to afford anything by way of real clarity to the colossal problems of plurality. It is a time for the re-assertion for independent histories, and for a rigorous working through of essential complexities that re-affirm that we all… yes, we all… possess a shared history and that we, individually, bear the burden of that history. One is reminded here of Hannah Arendt. She discerned “…the quality of being a person as distinguished from being mere human..,” emphasising that speaking about a moral personality is almost redundancy. She added: “In the process of thought in which I actualize the specifically human difference of speech, I explicitly constitute myself [as] a person, and I shall remain one to the extent that I am capable of such constitution ever again and anew.” |

|

Pepita Seth was born in England, and spent her younger days as a film editor, working with directors such as Stanley Donen and Ted Kotcheff. She came to India in the early 1970s, and began photographing and writing about the ritual traditions of Kerala. She remains the only foreigner who has been granted official permission to enter the temples of Kerala. Her works include Heaven on Earth, a monumental documentation on the Guruvayur Temple. Her current research is in Theyyam, a multi-faceted ritualistic performance of Kerala.

|

Eddin Khoo is one of the most important cultural activists and thinkers in today’s Malaysia. A poet, writer, journalist, translator and teacher, he is the founder of PUSAKA – Centre for Culture, Tradition, Ideas – a cultural organisation dedicated to studying and preserving forms of traditional and ritual theatre. A self-described half-Chinese, half-Indian mix, the translator of Moby Dick, an expert on Islamic art, a political analyst, since 2002 Khoo has been tirelessly working to revive the tradition of Wayang Kulit, Malaysian shadow puppetry.

|

Disclaimers: The opinions expressed by the writers are their own. They do not represent their institutions’ view.

LILA Inter-actions will not be responsible for the views presented.

The images and the videos used are only intended to provide multiple perspectives on the fields under discussion.

Images & video courtesy: Leichenengel | Pepita Seth | NDLA | Sergey Moskalev | Sentausa

Share this debate… |

… follow LILA… |

||||

It is not infrequently said that whenever a certain statement is made about India the exact opposite is equally true. So if I say that I have been very kindly treated here, it does not mean that I am unaware of other scenarios, not appalled by them or that I, in any way, condone them.

It is not infrequently said that whenever a certain statement is made about India the exact opposite is equally true. So if I say that I have been very kindly treated here, it does not mean that I am unaware of other scenarios, not appalled by them or that I, in any way, condone them.

It may be somewhat perverse to commence a ‘provocation’ on multi-culturalism by invoking the image of V.S Naipaul convulsing, shaking his fists, at the very prospect of the (then) recently espoused concept of the “multi-culti” in Blair’s Britain. The haughty Knight’s judgment: “a barbarism.”

It may be somewhat perverse to commence a ‘provocation’ on multi-culturalism by invoking the image of V.S Naipaul convulsing, shaking his fists, at the very prospect of the (then) recently espoused concept of the “multi-culti” in Blair’s Britain. The haughty Knight’s judgment: “a barbarism.”