I’ve been ‘rewilding’ in the desert now for a little more than 16 years. And a question I’m often asked is: Have you noticed any signs of Climate Change?

The answer is ‘No’. It’s a bit like watching grass growing – it happens much too slowly to see, and it isn’t at all certain that unusual events (like more rain one year, or more localized rain) are random, aberrant occurrences or part of a strong Climate Change pattern. Which is not to deny that Climate Change is happening in the desert. It just isn’t that obvious or easy to see and pin down. Not like melting glaciers.

If you take a long view stretching over much larger spans of time, then the Thar desert exemplifies Climate Change with its relict landscapes from former, wetter times. Fossils of gymnosperm trees at Akal Fossil Park in Jaisalmer are eloquent testimony. So are the remnants of beaches, lagoons and shallow continental shelves throughout Jaisalmer, Bikaner and Barmer from a time when a salty sea lapped much of what we know today as western Rajasthan. None of this is surprising. Deep time is all about change, mostly incremental change at a very slow pace, but it all adds up and can seem almost cataclysmic in cumulative effect.

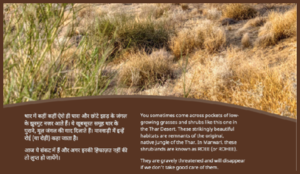

What does seem to be happening in the Thar desert – and I’m speaking mostly about the districts of Jaisalmer, Barmer and Jodhpur which I know better than others – is the retreat of a landscape that is characteristic for this south-eastern corner of the great band of desert lands that stretch westwards all the way to northern Africa. I refer to a community of plants and a habitat that I’ve learnt to call ‘Roee’.

Travelling in the desert looking for seeds, we would see patches of a kind of shrubland that seemed, somehow, to be older, more attuned to the desert, completely adapted to its difficult home. In between, we’d find disturbed tracts, mined or planted, or in some other way disrupted, so that the shrublands were now only relict fragments, usually quite small.

We would ask shepherds what they called these shrublands, and they would look at us not really comprehending what we were asking about, and offer us geographic names. “No, no, don’t you have a name for this particular kind of landscape?” we’d ask. “What would you say if your camel wandered off into a patch of bui and seenio shrubland like this one?” And they’d look at us as if we were a bit loopy. City folk!

Until one day we met the owner of a tented encampment who told us, “Sure, we call it ‘Roee.’” We reached as soon as we could for Google and learnt that this word was used by Col. Todd traveling on his camel from Sindh to Jaisalmer in 1829. “The natural jungle of the Thar desert is called Roee,” he wrote.

We knew we had come across a generic word for the wild shrublands of the Thar. A word that could stand alongside all the other redolent names that describe xeric shrublands in western Australia, California, South Africa, and the northern rocky shores of the Mediterranean. Respectively: Mulga; Chaparral; Fynbos; Garrigue.

And now Roee.

The Thar desert is by no means uniform in its soils and geology. There are salty sand dunes, calcium-rich alkaline tracts, iron-rich sandstone, volcanic outcrops, dolomitic hills… All of them support variants of Roee shrublands with species that shift along with the minerals and pH of the soil.

Why is any of this of interest? Because we’d found a name for a characteristic shrubby wilderness – a name that needs to be inoculated into the vocabulary that people use for the Thar desert. Because foresters treat the desert as a vast wasteland – to be fed with canal water or irrigated by pipeline, in one way or another to be changed fundamentally to bring it in line with other places that are not considered ‘wastelands’.

Finding a local Marwari name for the natural shrublands of our desert region could be a first step in protecting what we know to be a valuable resource. Name it – and that could kickstart a cascading process of looking for it, recognising it, appreciating it, and eventually – hopefully – conserving it.

The fact that all these other shrublands in arid places around the world are greatly valued and carefully conserved will act as a spur to conserving our Roee. It’s still only a first step, but here’s hoping the word ‘roee’ will travel and be mouthed and repeated by people who travel into the desert, eventually to become as loved and valued as the wonderful desert minstrels – the Manganiars – who live there and sing the most beautiful songs.

To know more about the Roee and the journey of rewilding Kishan Bagh, watch this video interview of the author by the Science Gallery, Bengaluru: