31 March 2014Our time, as New Media theorist Dan Gillmor points out, is witnessing the first draft of history being written, in part, by the former audience. We have come a long way from McLuhan’s original moment — we take it for granted that the medium transforms itself into content in the frenzy of events. With the political theatre open 24/7 during the General Elections in India, contemporary media cannot but play out the drama. ‘Ethics’ has long been a museum term in the media business, and it does not surprise us any longer when competent journalists are disgraced and shown the door for taking a stand. In the era of empty rhetoric and ideology sale, what can bring forth a responsible dynamic within the media? In this week’s Inter-actions, BRP Bhaskar assesses the terrain, from dominant mediums to regulatory boards, economic structures to educational institutions. In her response, Shashwati Goswami deplores the entertainment turn taken by most media, and warns against the danger of an imminent fatigue that might render the entire mediascape redundant. |

Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations and descriptions.

A Reality CheckBRP Bhaskar |

On Media FatigueShashwati Goswami |

|

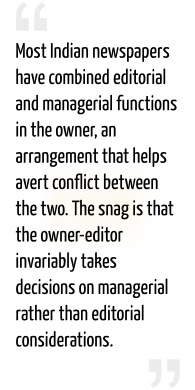

Are the recommendations of The Press Council The regulatory scene is multi-centred, too. The Press Council, established by law, decades ago, to deal with complaints against the print media, is still there, but newspapers do not take it seriously any longer. They know it is toothless and do not accord it the respect which they once gave it. Its inability to tackle the pernicious issue of paid news testifies to its ineffectiveness. The electronic media is without a statutory regulatory mechanism. When there was talk of creating one, broadcasters hurriedly devised something in the name of self-regulation, which is no regulation at all. They unwittingly revealed their warped concept of media freedom when they held out a threat to black out Arvind Kejriwal, who had enraged them by talking of links between some news channels, a corporate leviathan and partisanship in the ongoing electoral battle. The social media, arguably the freest elsewhere in the world, is potentially subject to the most anti-democratic control in India, under a law which vests lower ranking cops with the authority to nab unwary users on flimsy grounds. The entire system cries for healthy self-regulation under a statutory framework. Hartosh Singh Bal recently left his position as political editor in Open Magazine, highlighting the tensions between editorial and managerial voices The media is afflicted with problems that stem from the state of the society as well as its own structural weaknesses. The Press Commission, which studied the relationship between owners and editors in the 1950s in the light of industrialists’ acquisition of control over newspapers, recognised the owner’s right to lay down the newspaper’s policy but sought to immunise the editor against interference in his day-to-day functioning. If the state could not find a way to rein in the owners even when its proclaimed goal was a socialistic pattern of society, how can it do so in the era of globalisation, which has made everything purchasable, the only thing to be negotiated being the price?

In some countries, ownership is not a contentious issue, since managerial control vests in professional publishers just as editorial control vests in professional journalists. Most Indian newspapers have combined editorial and managerial functions in the owner, an arrangement that helps avert conflict between the two. The snag is that the owner-editor invariably takes decisions on managerial rather than editorial considerations. While many newspapers have corporate structures, within their walls, feudal values and ways of functioning prevail. Ironically, the pattern is no different even in the electronic media sector, with its share of journalists-turned-entrepreneurs.

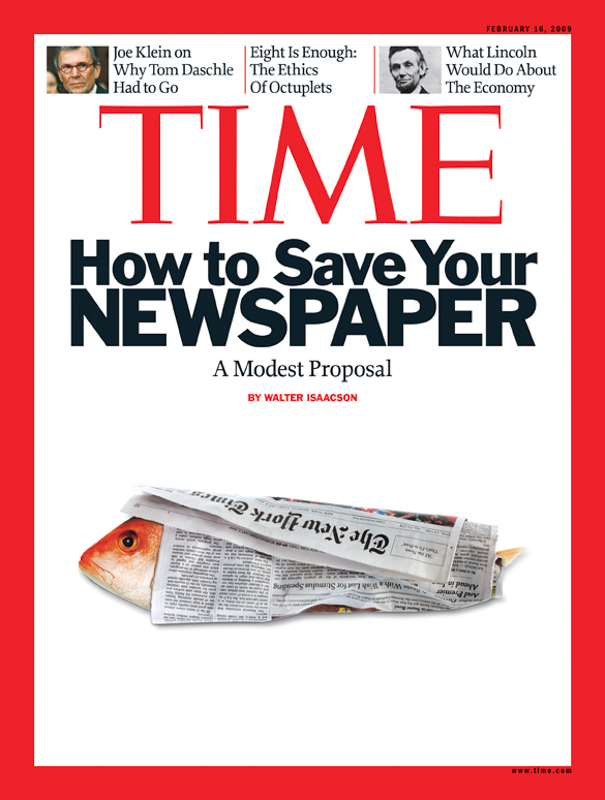

With the denigration, devaluation and even disappearance of the editor, professionalism is under severe strain in the print media. The commercial success of the Murdoch formula, which holds that the newspaper is just another product made to earn profit – a view the intelligent reader cannot accept as he knows the newspaper influences him in a way no other product does – has put practitioners of professional values under pressure. Talk of journalistic ethics has little relevance when newspaper owners put the seller above the producer and enter into private treaties with corporate entities. Since the media is an institution of Western origin, the tendency to ape Western models is understandable. However, the imitators need to remember that the Murdoch formula has not been able to prevent the demise of newspapers, which have outlived their utility. The newspapers that have managed to survive so far are those who, instead of trying to keep up with the channels, chose to concentrate on analysis and interpretation, tasks which the print media can do far more effectively than the electronic media. The ultimate folly the newspapers can commit is to compete with the television on its terms. A Time Magazine cover discussing At one end of the electronic spectrum are channels which, under journalists who honed their skills in the print media, are seeking to maintain professional values amid the ceaseless flow of Breaking News, which inevitably requires continuous lowering of standards to sustain viewer interest. At the other end are channels dominated by narcissist anchors suffering from delusions of grandeur and constantly haranguing their guests, studio audiences and the viewers in the name of the Nation or the People. While enterprising media persons venture into sting operations, the professionally weak fake them.

As the state’s monopoly over radio and television collapsed in the face of technological advances and economic liberalisation, the last quarter century witnessed an unprecedented media explosion with private channels leading the proliferation drive. Journalism training facilities also grew but not to the extent needed to meet the demand of the fast-growing job market. To make matters worse, the quality of training leaves much to be desired. Exposure to a wide range of subjects over a few months may be sufficient to prepare one for a journalistic career but does not really equip one for it. Few institutions have adequate facilities for practical training. The time has come to develop full-fledged journalism schools on the lines of the National Law School but the matter is yet to engage the attention of the state as well as newspaper owners and editors. All media is habit-forming. Those used to sensationalism cannot be weaned away from it easily. So the recovery process must necessarily be slow. The first step is for all concerned to realise that the solution to the problem lies in the strengthening of professionalism. Establishment of quality training facilities where prospective journalists can be provided good professional grounding can be a starting point. Collaboration between training institutions in India and those in other countries, including African and Latin American countries, to develop alternatives to the doomed Western model can be explored. The media needs to take note of not just the events but also the processes that lead to events, not just personalities but the broad contours of the society in which they operate. Reforms must not lead to a new kind of uniformity. The media must provide the public with real choices. |

There are nearly 800 television channels today in India Though we can call it growth of media in general, the effect has been more revolutionising for television than for any other platform. The contrast is rather obvious, as India had been a late entry into the field of television (only in 1959). Private television stations mushroomed in such a way that as of 29 March 2014, according to the I&B Ministry website, there are 792 permitted satellite television channels, of which 392 are news and current affairs channels, and the rest 400, entertainment-based channels. But the important question is, with this growth in numbers, are the people getting choices in content, and what exactly does the content consist of? A close look will show that media content has become more about entertainment and reality shows than the ‘real’ issues inflicting the society. It seems that the news channels are also convinced that only entertainment gets the desired eye-balls. This challenge of the ‘only entertainment’ television was very quickly accepted by the print and the radio. The print redesigned itself with almost 70% entertainment (barring a very few) and radio as 100% of it, in the form of private FM channels. It has not helped that the government had not allowed news and current affairs in private FM channels as well as ‘in incubation’ community radio. While analysing this deluge of entertainment in media, Erik Barnouw said that “entertainment has the merit not only of being suited to helping sell goods; it is an effective vehicle for hidden ideological messages” (The Sponsor, 1978). Herman and Chomsky called entertainment the contemporary equivalent of the Roman “games of circus;” which diverts the public from politics and generates a political apathy that becomes helpful to preserve the status quo. It is undeniable that television has a very strong role in constructing opinions about people and events. In the Third World, it is rather a constructed space moderated by the state and the market. This has given birth to what Adorno had called the culture industry. Here, culture is apolitical and bereft of ideological and philosophical understanding, more for plain entertainment rather than preservation of heritage and tradition. This outlook desensitises generations of citizens to genuine issues and creates a homogenised culture, which is unhealthy for a multi-cultural country like India.

In the process, we see a lot of disparate and somewhat cacophonic programmes that leave most of us confused and tired. It is interesting to observe how media picks up an issue like holy grail and drops another like hot coal. The December 2012 rape case made headlines and created near hysteria whereas the rampant raping of the Dalits in Indian villages never figure at all. Undeniably, the crusading role of the media during the December 2012 incident did bring about a drastic change in the rape law of the land, but did it really change the plight of the underprivileged? The issues of patriarchy and the lack of governance, as the core issues of such an incident, were never discussed. Had the laws reduced the number of rapes? We need to know, and as a crusader for the cause, is the media discussing the issue at all? In fact it conveniently moved on to the next big issue. The media did the same with the Anna Hazare movement and the Kejriwal wave – nurture it and claim success initially and all of a sudden drop the issue when it is either perceived as a threat or rendered useless for them. The same approach is visible when scams are covered by the media: the particular scam and the media house announcing it give a distinctive narrative of the political economy not only of the issue at hand, but also of the media house in question. As Pierre Bourdieu said, such selective news stories give “free rein to the unbridled construction of demagoguery (whether spontaneous or intentional) or can stir up great excitement by catering to the most primitive drives and emotions” (On Television, 1996). A TV news capture after the 2012 Delhi rape: This leads us to the issue of the usage of language in the media. How and why a question is posed, to whom, in what context, and then represented where, are always enigmas. Often, we see a channel vie for attention by saying that only its journalists had access to a particular breaking news. But if you surf the other channels, you will find that everyone is demanding the same. Then, you look at how the particular breaking news is treated and you find that almost every Prime Time News presenter is asking the same question, albeit in a different language. For example in the Devyani Khobragade episode, the channels made a martyr of the officer and drove the government to react quite naively. While there were far more contentious policy issues between India and the US, the channels conveniently ignored that and never raised the issue of national pride. Higher the pitch and more aggressive the nature of presentation, more attractive the programme! But this is not as benign as it seems to be. Another obnoxious way of the Prime Time ‘stars’ is to put words into others’ mouth. They put pressure on a person to utter words which are then edited and removed out of context and quoted rampantly. Such utterances obviously serve the purpose of the media house, but that is definitely damaging both for the issue as well as the person concerned. One often has a feeling that today’s journalists are not educated enough to handle any complex issue. The debate then comes down to whether journalism education should be made mandatory. A person goes through a long social and political conditioning from childhood to become what she or he is. A one or two year course cannot develop a sensitive journalist. But this does not mean that journalism education is useless. Our society must urgently begin to discuss this in greater depth.

In this uproar of the media, online platforms seem to offer a more democratic and analytical space. It is not that these platforms are not susceptible to various pressures. But, seeing the way this space is expanding, and how more and more young Indians are logging on to it, we may pin some hope onto those new spaces to give us genuine debates and deliberations, to breathe in fresh air into the mediascape. But it will take time, as the access to these platforms is very skewed as of now. The proliferation of media that India is witnessing often gives us a false sense of having choices. But do we have it in reality? Cross media ownership, dominant business model and the homogenised programming pattern leave, in fact, no space for healthy competition or even choices. However, even to sustain the hegemony that this corporate media aspires for, they need to understand that giving space for democratic and constructive as well as informed discussion and debates is a must. Else, media fatigue might seep in and the people might stop taking the media seriously. This, in turn, will be a threat to the edifice of a healthy democracy. |

|

BRP Bhaskar is a journalist and social activist. Starting his journalistic career more than six decades ago with The Hindu, BRP Bhaskar reported in and outside of India for various publications of the country: Statesman, Patriot, UNI, and Deccan Herald. He has covered the Philippines, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Kashmir and other destinations during heated eras. BRP Bhaskar later turned to the visual media: he was one of the major forces behind the creation of Asianet TV, the first privately owned television channel in Malayalam.

|

Shashwati Goswami is an Associate Professor at IIMC, New Delhi. Her areas of interest include Media Policy, Public Health Communication, Environment and Conflict Communication, Radio Broadcasting and Community Radio. She has worked extensively in the areas of Development-Induced Displacement and Urban Poverty. She is a recipient of Panos South Asia fellowship for conflict reporting and Rockefeller archive centre grant-in-aid for archival research in family planning communication. She is a native of Assam.

|

Disclaimers: The opinions expressed by the writers are their own. They do not represent their institutions’ view.

LILA Inter-actions will not be responsible for the views presented.

The images and the videos used are only intended to provide multiple perspectives on the fields under discussion.

Images & video courtesy: Hello-Magpie | The Hoot | TBIP | Media Bistro | Pakistan 33 | Financial Times | Metro and You | IBN Live

Share this debate… |

… follow LILA… |

||||

The Indian media landscape today presents a curiously variegated picture. Television, which is now the primary source of information on local, national and international developments, seems very vibrant but a close look reveals it to be a more flamboyant and flippant medium than factual. Newspapers, which have built up a fair reputation for professionalism over two and a half centuries – thanks to the early editors’ commitment to certain values and concerns for issues that matter – are fighting hard to avert the disaster that has overtaken their Western counterparts. The new media, which are still in their infancy, have opened up a world for those who earlier did not have access to any kind of mass media – they can now communicate with anyone who cares to listen.

The Indian media landscape today presents a curiously variegated picture. Television, which is now the primary source of information on local, national and international developments, seems very vibrant but a close look reveals it to be a more flamboyant and flippant medium than factual. Newspapers, which have built up a fair reputation for professionalism over two and a half centuries – thanks to the early editors’ commitment to certain values and concerns for issues that matter – are fighting hard to avert the disaster that has overtaken their Western counterparts. The new media, which are still in their infancy, have opened up a world for those who earlier did not have access to any kind of mass media – they can now communicate with anyone who cares to listen.

Media in independent India has been growing and expanding in a state of policy vacuum from its inception. There has been no written policy envisaging the relationship of the growth of media with that of national development. The growth, if any, occurred either due to political patronage or as a reaction to a certain context or development. For example, radio or television stations were set up in those places where a direct control from Delhi was easier. Stations were set up in Punjab after partition, in Jammu and Kashmir after the first battle over control of Kashmir, and in the Northeast after the 1962 Chinese aggression. That situation changed with the economic reforms of the 1990s. The flood gate of media control was released, leading to the phenomenal growth of media within the following decades.

Media in independent India has been growing and expanding in a state of policy vacuum from its inception. There has been no written policy envisaging the relationship of the growth of media with that of national development. The growth, if any, occurred either due to political patronage or as a reaction to a certain context or development. For example, radio or television stations were set up in those places where a direct control from Delhi was easier. Stations were set up in Punjab after partition, in Jammu and Kashmir after the first battle over control of Kashmir, and in the Northeast after the 1962 Chinese aggression. That situation changed with the economic reforms of the 1990s. The flood gate of media control was released, leading to the phenomenal growth of media within the following decades.