26 May 2014Today, the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) is forming a new government in India. For the first time since 1984, a single political party has got the majority of the seats in the lower house of the Parliament. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) having won 282 out of the 543 seats in the 16th Lok Sabha, will now be the deciding authority at the Centre. Apparently, Narendra Modi, who is set to swear in this evening as the Prime Minister of India, was the mastermind and the key player engineering this success, based on a hugely advertised ‘development’ agenda, thus bringing the ‘Coalition Era’ to an end. A lot of hope has been generated among various sections of the society, but, given the Hindu Nationalist background of the BJP, fear and scepticism abound, too. Even if 70% of the electorate votes against a party, it is possible for it to get a clear majority in the house: the irony of calling ours a representative democracy is stark here. In this week’s Inter-actions, Sudheendra Kulkarni assesses without concessions the deficiencies of the supposedly democratic institutions in the country. Ananya Vajpeyi returns to the election results and reflects on how to reclaim secular times for India. |

Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations and descriptions.

Partnership in DemocracySudheendra Kulkarni |

Reinventing SecularismAnanya Vajpeyi |

||||||||

Requested file could not be found (error code 404). Verify the file URL specified in the shortcode. |

Listen |

Listen |

Requested file could not be found (error code 404). Verify the file URL specified in the shortcode. |

||||||

|

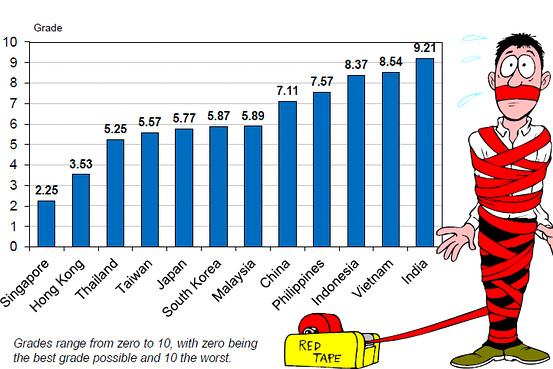

Today, 26 May 2014, India gets a new government of the National Democratic Alliance, led by the Bharatiya Janata Party. Governments come and go on a periodic basis in a multi-party democracy like ours. In some ways, the voting out and voting in of parties and coalitions is good for democracy, because it serves as a reminder to them that the people can punish non-performance and non-fulfilment of promises. It also confirms that the people themselves have the power to change governments, reducing, at least to some extent, the cynicism and pessimism that otherwise dominate the attitude of a large section of society. Thus, change of governments and leaders in an orderly manner nurtures the self-renewing impulses in a democracy. However, the litmus test of the vibrancy of a democracy is not limited to the periodic change of governments and leaders. Rather, it resides in how efficacious, responsive and responsible the permanent institutions of democracy are. But at this level, the situation is rather alarming: the critical shortcomings in India’s democratic system of governance are deeply ingrained and multifarious. One has to be blind not to see the rot that has spread in almost all our democratic institutions. Parliament is not performing diligently its job of law-making, reviewing of the performance of the executive, and debating of serious issues confronting the nation and society. The political leadership of the executive is, by and large, less concerned with the tasks of good governance than with managing narrow political and business interests for personal and sectional benefit. Exceptions apart, ministerial positions are not primarily given on the criterion of competence and commitment to public good. And when competence and integrity are discounted at the level of political leadership, it percolates and harms the integrity and efficacy of other democratic institutions as well. A comparison of bureaucracy’s deficiencies, Bureaucracy, which forms the non-temporary structure of the executive (unlike the political leadership of the executive that keeps changing) is equally touched. Although there are many conscientious and service-oriented bureaucrats, its system, as a whole, has repeatedly failed to fulfil the needs and democratic aspirations of the common people. Even though the Right to Information Act has introduced a limited degree of transparency in the way the government functions, there are no accountability norms for civil servants and there is hardly any scope for social monitoring and audit of government offices.

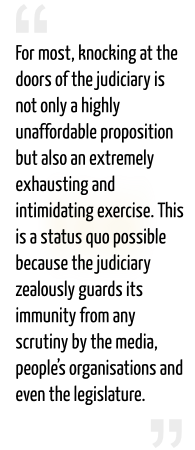

The judiciary in India is fairly independent, and must remain so. But for most, knocking at the doors of the judiciary is not only a highly unaffordable proposition but also an extremely exhausting and intimidating exercise. This is a status quo possible because the judiciary zealously guards its immunity from any scrutiny by the media, people’s organisations and even the legislature. And since many MPs, MLAs and ministers themselves lack integrity ─ worse still, several of them have criminal cases against them ─ they cannot logically summon the moral authority to ask the judiciary to put its house in order. The police – the everyday face of law – have also lost all of the people’s trust and confidence. Corruption and high-handedness are rampant. The police reserve their protective function more for the rich and the criminals, and less for the poor and the needy. The new Prime Minister has promised ‘Minimum Government, Maximum Governance’, but we are still waiting to hear how he is going to achieve this laudable goal. Whatever may be his ideas on moving towards this objective, he obviously has to invest a lot of political will into the exercise of reforming the institutions of democratic governance. If democracy is one pillar of the Indian Republic, secularism is the other. The new Prime Minister should be prepared to engage in a lot of heated debates on secularism, both inside and outside Parliament, in the months to come. This is because, unfortunately, both the concept and practice of secularism have become contentious, as was once again revealed in the campaign for the just-concluded parliamentary elections. Secularism, understood as ‘equal respect for all faiths’, has been the hallmark of Indian society and civilisation, but harmony among various faith communities has also not always presented a satisfactory picture. In particular, the Partition of India in 1947 on the basis of the spurious Two-Nation theory has left a trail of alienation between Hindus and Muslims, even though, fortunately, many points of syncretism in the cultures, customs and religious practices of the two communities still survive from the past. Actually, the threats to secularism come less from society than from electoral politics. The two parties that call themselves secular, and also those that harangue against secularism, have been guilty of trying to consolidate the vote banks of one or the other religious community for the purpose of gaining electoral success. Political rivalries routinely contribute to the exacerbation of local-level communal tensions that sometimes snowball into violent conflicts on a larger scale, resulting in the killing of innocent persons. Of course, larger national and international issues also sometimes feed into communal prejudices. Minimising communal tension, and preventing it from erupting into riots, is going to be one of the biggest challenges before Narendra Modi’s government. This challenge can be met only by forging a close cooperation between the central and state governments, with both demonstrating equal resolve to defend secularism in letter and spirit. In particular, they must make extra efforts to ensure that communal prejudices do not colour the attitudes and actions of the functionaries of democratic institutions. But, as we know, unfortunately, the police in India are not always unbiased in tackling incidents of communal violence. Innocent Muslims routinely suffer more loss of life and property in such situations, while the administration often shows disinclination to implement schemes and policies aimed at the welfare of Muslims. Soon after the counting of votes was over, Modi assured the nation that he would become a ‘Warrior of Development’. Reiterating the slogan of his party ‘Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas’, he also reasserted non-discrimination as the corner stone of his governance. But he did not explicitly promise that secularism would be safe under his watch. Therefore, it is necessary for all principled believers in the tenets of ‘inclusive development’ and ‘equal respect for all faiths’ to become ‘Warriors of both Development… and Secularism’. The question is how can we strengthen the democratic and secular character of the institutions of governance in India. Experience shows that this important mission cannot be left to political parties and leaders alone. India needs a great mass awakening and sustained mass activism to keep governments and political parties on the right track. This awakening and activism has to be on democratic and nonviolent lines, for any transformative effort that relies on violence unfailingly fails, besides heaping more miseries on the people.

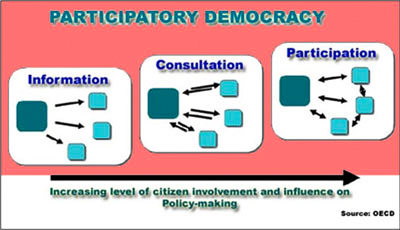

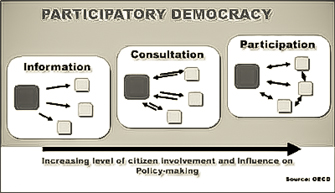

Is nonviolent change possible? Yes, it is. The first and foremost requirement for this is to realise that people’s right ─ but also their duty ─ in a democracy does not end with voting in elections once in five years. The educated and socially conscious people, in particular, have to be vigilant and active all the time. They must force political and governance functionaries to come out of their comfort zones and confront the problems before our society and nation. As a matter of fact, there are literally hundreds of thousands of small, local-level efforts going on in India to strengthen the roots of democracy, secularism, good governance and equitable development. These efforts must continue, and grow in scale, intensity and connectivity. Democracy is not a system of governance in which the people, mute watchers, give a contract to a certain party or alliance of parties to govern them for five years. Democratic governance has to be an active partnership between the government and the people, in which enlightened and nonchalant members of society serve as both constructive collaborators with, and keen watchdogs for, those in power. This alone is the way forward to strengthen democratic culture and institutions in India. |

Ever since Partition and Independence, Indian political life has privileged the concepts of diversity, pluralism, tolerance and inter-religious harmony. The way to realise these values, according to the ideology dominant thus far, was to have a state that expressed equal ‘love’ for all communities, that is, a state taking it upon itself to safeguard the peculiarities, rights and interests of groups defined along the axes of religion or caste, or as a majority and multiple minorities. As Pratap Bhanu Mehta has explained recently, in the vision of its founders and the architecture of the Constitution, India was conceived of as a ‘federation of communities’ with a paternalistic, secular state presiding over and managing a mosaic of identities. But, the outcome of India’s 2014 general elections, which puts the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in power under the leadership of Narendra Modi – to be sworn in as the new prime minister today, Monday 26 May – calls for a widespread debate on the meaning, purpose and definition of secularism in this country. 31% of the Indian electorate has voted for the BJP. Three distinct reasons may be construed as the rationale for the party’s success. First, to give the BJP the opportunity to deliver on its promise of economic growth, infrastructure development and good governance. Second, to punish the incumbent Congress-led government, in power from 2004 to 2014, for its inefficiency, massive corruption, misrule, ideological confusion, institutional collapse, schizophrenic economic policies, dynastic style of functioning and plutocratic leadership. And third, to remake India according to the tenets of Hindutva, or political Hindu nationalism. The last factor can account for only some of the BJP’s popularity. Nation-wide, 8-9% of the Muslim voters, 24-27% of Dalits, as well as huge numbers of secular Hindus voted for the BJP. They might have stayed loyal to the Congress had it not been for its colossal failure to rule India properly (especially since 2010), or if it had managed to put on a credible election campaign in 2014. They voted BJP, but certainly not because they wanted a Hindu majoritarian state to replace the familiar collective project expressed by Rabindranath Tagore’s phrase: “unity in diversity”. The Anthem of Our Pluralistic Spirit

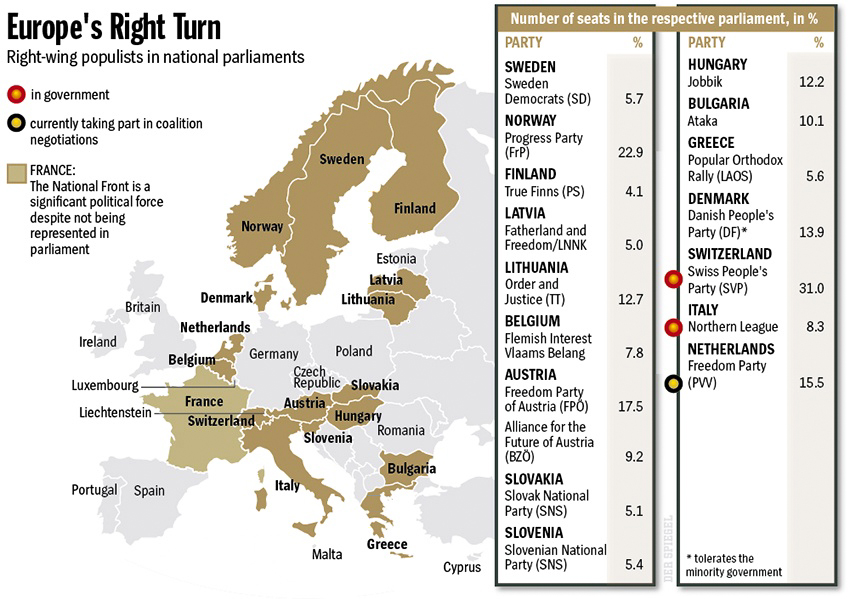

I would reckon that most people who voted for the BJP did so because of a combination of the first two aforementioned factors. That being said, having gotten the numbers, and in the absence of a strong opposition, there is nothing really to stop the new government from pursuing an anti-secular ideological agenda, along with its more pragmatic objective of getting India back on the growth track. The Congress, and the Left – another routed camp in this election – had projected secularism for the past 60-70 years largely in terms of a certain rhetoric, combined with the now reviled and abhorred tactics of ‘minority appeasement’ and ‘vote banks’. But today, the defining features of conventional secularism have lost both their political rewards and their moral luster. It may turn out that the Indian voter is willing to let go altogether of secularism as-we-knew-it, in the interest of building a more prosperous, stable and strong state. Our democracy has now elected a political party that has a history of aligning itself with, and seeking to represent mainly the Hindus, the majority community. This party believes that India ought to be a nation for, of and by the people of one group: a Hindu Rashtra. The BJP, together with its allies in the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), has a clear majority in Parliament, and, needing no coalition partners to form the government, it has unequivocally chosen Modi as the country’s next PM. By contrast, all other parties, including the Indian National Congress (Congress) and the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), are electorally so weakened that none of them may be designated the leader of the opposition. This means that the BJP has the field absolutely clear to set India on a course to become a Hindu majoritarian nation-state, turning more sharply to the right than anyone could have imagined or predicted even a few months ago. The BJP’s ideology of Hindutva could replace what has been the official ideology of the Nehruvian and post-Nehruvian state thus far, that is, secularism. Modi has the necessary democratic mandate to achieve this tectonic shift in the very character of the Indian state. Europe’s right wing awakening, by Der Spiegel In fact, the mandate of the world’s largest and most diverse electorate is united by only one thing: its desperate need for change, and the hope that India will get back to a double-digit growth rate. The worry, now, is that the incoming NDA government, under Modi’s leadership, will take the popular vote of confidence and run with it, treating it not so much as a firm ouster for the previous administration, but instead, as a free hand to introduce more clearly majoritarian, authoritarian, communal, and neo-liberal policies than anyone has seen in India’s political culture. Given the drift towards the right in numerous countries across the democratic world – both in terms of cultural politics and economic policy – as well as the return of authoritarian, neo-nationalist, fascist, and supremacist parties and movements in many parts of Europe and the Middle East, Modi is not unique as a phenomenon. But the foundations of the modern Indian polity were inspired by Tagorean and Gandhian ideals of communal harmony, non-violence, peaceful coexistence and the suspicion of conventional nationalism. These were validated and reinforced in the trajectory of the postcolonial Indian state set by Nehru, a committed secularist. Thus, both the BJP’s overwhelming electoral victory and Modi’s personal appeal for hundreds of millions of ordinary Indians are surprising developments, to say the least. More frightening is the apparent willingness of the BJP’s new-found supporters to move on from the pogrom of Muslims in Gujarat in 2002, a hideous orgy of sectarian violence against the minority community, which left more than a thousand dead, besides several thousands displaced – with most of the affected being Muslim. Modi had avoided all responsibility for these events, even though he was Chief Minister of Gujarat at the time. Those who believe in secularism as a core normative aspect of the Indian political system, never to be sacrificed at the altar of a high growth rate; those who believe in substantive and not just formal equality, dignity, justice and opportunities for minorities; those who value India’s mind-boggling cultural diversity, and those who stand by the Constitution of India – all such people have to now come together to re-imagine ways and means to preserve and strengthen our endangered pluralist ethos. Repeating tired and discredited slogans left over from decades of Congress rule will no longer suffice.

These elections were not a coup. They were free and fair. Regime change is not taking place in a climate of civil war. We must respect the election results. For liberals like us, time has come for introspection. Unfortunately, the concept of secularism has been hijacked, ill-treated by the Congress Party. The very word is now discredited. There is the perception that it is an empty idea, a lie, the means for a postcolonial elite to conserve its privileges. There is an intellectual crisis of secularism in India. We cannot anymore be content in repeating: “Modi is a new Hitler”. We must ask ourselves what does not work anymore and why we have been so disconnected from what is apparently a broad popular consensus. India’s liberals must rethink what they believe in. We have to understand what it means to be secular, not with the patronage of a loose and careless state with a decadent habit of minority appeasement, but against the grain of the regnant power and its attendant ideology that is unambiguously exclusivist. The time for lazy assumptions about India’s essentially accommodative and mixed nature, its supposed comfort with its own superabundance of conflicting identities, and its fabled ability to manage differences – that time is now over. If we don’t reinvent secularism, we will forfeit it. |

||||||||

|

Sudheendra Kulkarni is a columnist and socio-political activist. He has been politically active with the CPI(M), before turning to the BJP. He was an aide, speech-writer and strategist to Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and secretary to Lal Krishna Advani. He is also the author of Music of the Spinning Wheel: Mahatma Gandhi’s Manifesto for the Internet Age (Amaryllis, 2012).

|

Ananya Vajpeyi is an Associate Fellow at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, New Delhi. She is the author of the award-winning book, Righteous Republic: The Political Foundations of Modern India (Harvard University Press, 2012). Vajpeyi was recently appointed a Global Ethics Fellow by the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, 2014-2017. She is currently writing a life of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar.

|

||||||||

Disclaimers: The opinions expressed by the writers are their own. They do not represent their institutions’ view.

LILA Inter-actions will not be responsible for the views presented.

The images and the videos used are only intended to provide multiple perspectives on the fields under discussion.

Images courtesy: Wikipedia | India Real Time | Khaleej Times | The Hindu | India Rising | Spiegel

Voices courtesy: Anonymous LILA Friends

Share this debate… |

… follow LILA… |

||||