|

19 September 2014

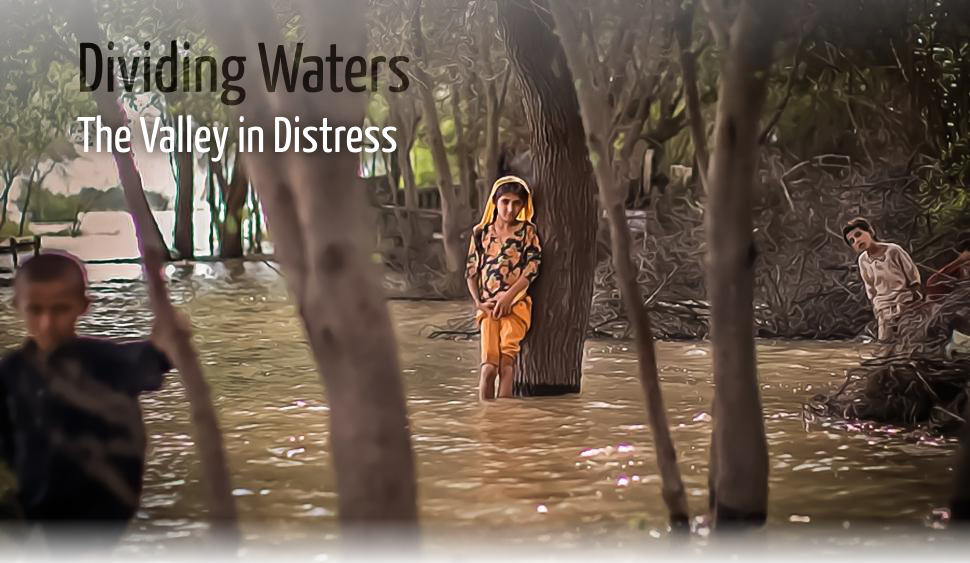

Miles away from the flood-affected Valley, the ground seems firm in India’s mega-cities. Journalists, politicians and administrators pat each other’s back on the successes of the rescue efforts, and deservedly so. It is another matter that just a few months ago, warnings were disregarded as unreal prophesies. Today, even as the bleary-eyed land slowly recoups its resolve, it seems, some essential lessons the waters threw us have been missed, like airdropped food packets. Perhaps, after another year, when time proves again its cyclicality, frantic searches might be launched to retrieve them. The Valley reminds us how our understanding of, and responses to, cataclysms clearly point to the alarming discontinuity that is increasingly qualifying our relationship with nature. Every day, our professional world moves us a little further away from the cardinal social functions that have built humanity. Our office hours do everything but help us recall the fundamental objective of work as organising the social repartition of nature’s resources. Our education, before that, apparently gave up the practice of interacting with and understanding the material cultures of each of our learning spaces. How do we manage these disasters? In this week’s LILA Inter-actions, Somnath Bandyopadhyay regrets the logic of media agendas that increasingly surfaces after each natural event, and he sees in the very concept of ‘disaster management’ the cause of our helplessness. Nirmal Selvamony goes two millennia back in time to see, already in the earliest attempts of environment control, the immediate reaffirmation of nature’s demand for freedom.

Debate

Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations.

|

|

We started on the wrong note anyway. Floods were routinely explained in school textbooks as natural disasters. We grew up learning about the river Damodar as the ‘sorrow of Bengal’, and later the river Kosi as the ‘sorrow of Bihar’. With barely a trickle in its river bed for most of the year, the former has been all but erased from public memory, while the latter continues to make occasional headlines for those who care about the backwaters in a poor state.

The speed of reaction of the administration

and the media has been particularly remarked

While floods in Kosi did not matter much to people outside the region, Uttarakhand was a popular pilgrimage for many Indians and shook the collective consciousness with images of Shiva and Kedarnath besieged by muddied waters. Floods in Srinagar go a step further. Kashmir evokes international interest. The world watched as the Indian government evacuated nearly 250,000 people, which was not only a gigantic rescue operation but also an exercise in public relations and political expediency. During the visit of the Chinese premier, there have been subtle references to China evacuating nearly 220,000 people in Sichuan province in 2013.

The timing is right, the issue is emotive and we have proved our capacity. Floods are a wonderful way to showcase our preparedness and management efficiency, perfected through rigorous, and repeated, rehearsals. Kudos to the script writers, trainers and performers to pull off a great show, yet again.

However, in order to give birth to the new discipline called Disaster Management, we needed to create disasters, often where they did not exist. Floods are a perfect example. These were natural phenomena whose location and timing could be predicted to a reasonable extent. That is, until the flood control measures, such as dams and embankments, kicked in. Then, it was only the managers of these facilities who were able to predict, since the floods were now more strongly related to the inherent limits of the technical measures adopted. Let us explore this fallacy from the following three dimensions.

First, the unique variability of water availability in time and space. Roughly, over two-thirds of the gross annual precipitation in India are concentrated during one-third of the year, a period we refer to as the monsoon season. Moreover, nearly two-thirds of this gross precipitation are concentrated over a third of India’s total geographical spread – the Ganga basin. It is indeed surprising that while we do know that there are sharp spikes in rainfall and associated run-off during some parts of the year, we continue to claim the rivers’ natural pathways for human habitation and other development needs. The rivers need their own room, and if people encroach upon it, floods show no mercy while forcibly evacuating them.

Rivers’ merciless defences

Second, floods in the Himalayan foothills are not just about water. The images of floodwaters either in Srinagar or Uttarakhand are not blue. They are indeed more mud than water. And this is another unique feature of our floods. The Himalayas are the youngest mountain ranges in the world, geologically speaking, and have folded as the sea-shores of north India and south China collided. The mountains are nothing but high-altitude sea-beds. Heavy, seasonal rains over the Himalayas are akin to pouring a bucket of water over a sand-castle. Yes, forest cover does play a role in reducing the impact of a deluge, but much like a week-old algal bed over the sand-castle. The sediment that flows down is a problem today but we forget that this is how the Gangetic plains were created in the first place, enabling one of the world’s oldest civilisations to flourish.

Third, floods remain a civilisational paradox for human societies. While floodplains provided the best conditions for early human civilisation by dramatically reducing efforts in growing food (and offering leisure to pursue other intellectual growth opportunities), it also generated a sense of mastery over the very same natural factors. Success of small interventions for irrigation and management of flood waters provided the basis for large-scale, serious engineering features that have become the norm today. Large human settlements have formed, with scant regard for the natural drainage channels or numerous water-bodies in the region. Roads have been constructed that impound water and alter the natural drainage systems. Creating reservoirs over riverbeds appear to be a sound option for generating much needed water and power for such habitations, strengthened as they are by the training and experience derived largely from the west. And quarterly profit statements of infrastructure companies take precedence over inevitable disasters that occur a few years later. Of course, the disaster management machinery kicks in then shifting the focus to the impact of a disaster rather than its making.

In order to extricate ourselves from the vicious cycle of faulty planning based on technological arrogance, we need to understand the origin of our ignorance. The influence of western education might provide a start. Such as, describing floods as natural disasters. Examples are all over. We associate ‘drainage’ with both riverbeds as well as sewer systems. In many modern habitations, Delhi being a prime example, these are barely distinguishable. We routinely confuse wetlands with wastelands, which are either ‘reclaimed’ as land or left to be truly wasted. Srinagar has reportedly reclaimed 60 percent of its water bodies for urban development.

Drainage, riverbeds and sewer systems:

popular echoes of our confusions

However, it does not explain all. Embankments were created along the river Damodar during British India, leading to widespread waterlogging and malaria. Lessons were learnt, and the very same embankments were dismantled with no further embankments being created till the end of the British rule in India. It was scientists and engineers in independent India who resurrected the notions of active flood control, supported by a centralised planning mechanism. As the lone crusader for rational approach to floods in India, Dr Dinesh Mishra, states that floods were like a domesticated cat which lived in harmony with households. We have now turned it into a tiger, and wonder how to live with it.

We are indeed riding a tiger in our dealings with modern floods in the sub-Himalayan regions, and catastrophic outcomes are only to be expected as long as our notions of disasters persist.

|

One of the major causes of the ‘extreme weather events’ of the present millennium – the floods of Mumbai in 2005, Uttar Pradesh in 2011, Assam in 2012, Uttarakhand in 2013, every year in Bihar and the most recent ones in Jammu and Kashmir this year – is but one thing: ‘development.’ The private and governmental ‘developers’ adopted various strategies: the destruction of natural ecosystems, like the mangroves along Mithi River and Mahim Creek in Mumbai, forests in Assam, mountain ecosystems in Uttarkhand, forest lands in Uttar Pradesh, forests in the middle hills of Nepal and the wetlands and the Dal lake in Kashmir; the creation of settlement in low-lying areas, like Dharavi, Bandra-Kurla Complex, and Chembur in Mumbai and Hazuri Bagh, Rajbagh and Jawahar Nagar in Kashmir, and the exceeding of the carrying capacity of a place. Development is not merely an economic-political term, it is, in the final analysis, an ecological one that presupposes an anti-ecological relation on the part of humans to the non-human world. Since all catastrophic floods are about the relation between the humans and water, we might do well to ponder briefly over this particular relation.

With economic liberalisation and the implementation of the New Economic Policy in the early nineties, water has become an industrial commodity. No more a part of the commons, water has now been brought to the market (national and international) to be bought and sold. True, the Industrial Revolution itself began in the eighteenth century, but the commodification of water in India occurred only in the twentieth century. Such an approach to one of the five natural elements was necessitated by the rarity of clean drinking water and the progressive degradation and loss of the water sources in the country. The problem has reached a crisis stage that has the potential to break out as a national or international water war.

Increasing needs for clean, drinkable water

contributed to the commodification of the element

We may want to compare this scenario with that of the pre-industrial state society. Significantly, the rise of the state society in Tamil Nadu, sometime during the beginning of the Christian era, coincided with water regulation, a sort of pre-modern developmental activity. Development is a typical enterprise of the state society based on a hierarchic relation between humans and the non-human world. Abandoning the earlier kinship relation to nature, Karikaalan, an eminent king of the country of Coozar, regarded water as “something to be tamed, managed, and harnessed.” Emboldened by this new attitude to water, he built, probably in 11 BCE, the first-ever diversionary dam across Kaaviri. One of the oldest such dams in the world, his kallaNai (Grand Anicut) is an engineering marvel, the prototype of all later water-diversionary and regulatory devices in India, as well as the first major monocultural (anti-ecological), large-scale irrigated agricultural endeavor. The dam divided Kaaviri into three streams – the Kollidam, Kaaviri and Vennaaru rivers – to irrigate about twelve lakh acres of land. His state saw water as a power that had to be enslaved (not unlike the 12,000 Sinhalese slaves he employed in the construction of the banks of the river) in order to increase state revenue necessary to maintain the huge governmental machinery and its exploits.

KallaNai: the world’s first dam

Besides being a radical politico-economic feat, the Grand Anicut brought about a paradigmatic shift in the social order itself. It gave the old primal social order a decent burial and effected the birth of a new one known as ‘the state.’ The new ‘dam’ (water regulator) set the earlier egalitarian tiNai societies (based on scrublands, mountains, arid tracts, riverine plains and seacoasts) in a hierarchic relation – a necessary condition for development – in which the riverine society gained ascendancy over the other four. In the case of South India, the hierarchisation of tiNai societies, brought about by a new water management project, coincides with the casteisation of the communities. Across centuries, several people did see social stratification as enslavement, but full-fledged emancipatory attempts were made only during the industrial society. Though social enslavement in South India is coterminous with the enslavement of water, no concerted efforts have been made yet to free the enslaved water and stand up for its status, rights and intrinsic value.

However, water was not always regarded as a slave, and what is worse, as a slave who could be traded in a market. In the primal era, before the emergence of the state society, water was a free being like the other four natural elements. In fact, humans and water stood in a kinship relation, and the river was looked upon as a mother. Nobody ever saw her as an avatar of a rebellious slave, as in the history of Carlota, a woman who led the Slave Revolt of 1843 in Cuba. When it rained in the mountains, the rivers swelled and the freshet was not seen as a catastrophe but as a source of nourishment and happiness. In fact, floods bonded the society better by gathering people near and in the free-flowing water to celebrate and worship her (as evident in the songs of Paripaatal). Floods were not catastrophic then, because those who lived along the banks of rivers were indigenous to those places and knew how they could symbiotically coexist with the living river, as peaceful and temperamental as themselves. They were not so foolish as to build their houses in low-lying areas and get washed away. It was only in the anarchic industrial era that rivers like Vaikai, in the words of A.K. Ramanujan,

carried off three village houses

one pregnant woman

and a couple of cows

named Gopi and Brinda as usual”

A River

Early societies, ancient wisdoms on nature’s behaviours

If water is a free being in the primal society, she is made a slave in the state society through developmental water management. In the industrial society, like ours, she is marketed and subjected to all forms of developmental persecution. Not being able to tolerate the human postures of development, water ultimately turns out to be a rebellious and catastrophic Carlota who menaces her captors and refuses to be repressed. Do we have the political will to set her free?

|