31 October 2014Politics, policy and politeness. How many signs of our past have we turned into “polite meaningless words,” as our historical consciousness makes of the past too comfortable an evidence? Easter, 1916 or the October Revolution, was not meant literally, specifically, punctually: they conveyed processes rather than events, freedom rather than destinies, action rather than observation. On our October, 1984, Satwant Singh and Beant Singh pressed just their triggers, once, twice, but they triggered the complex acceleration of a poisonous turn of events. The chronology of events has become a familiar story for us, but the impatient backward look of the present often forgets the underestimated open-endedness of each incident. Indira Gandhi’s assassination was not simply the consequence of the Operation Blue Star – five full months passed between the two events, and thousands of mindful and patient decisions could have been taken by hundreds of administrators, party leaders, NGO voices, and ordinary citizens, to bridge the gap with the actual, existing spirit of cutural tolerance shared by the millions. Communal agendas are not a structural necessity in a parliamentary democracy; they are the easy game of a political culture understanding governance as reaction, and vision as planning. The thirtieth anniversary of the 1984 Sikh riots, to recall and always vivify our awareness of the tragic risks of uninspired reigns. And to realise that real foresight is a vital ingredient in the synthesis of a society. This week on LILA Inter-actions, Hartosh Singh Bal returns on the recent controversy of the ban of the film Kaum De Heere, to understand today’s climate of ideological filtering as a tragic parody to a genuine culture of dialogue. Vikram Kapur reflects on the incredible gravity that just a few days can have on the lives of millions, for decades, and he finds in the idea of memorials, the many peaceful ways to live with our past. Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations. |

|||||||||

A Requirement for CoexistenceHartosh Singh Bal |

The Memorial or the StreetVikram Kapur |

||||||||

Requested file could not be found (error code 404). Verify the file URL specified in the shortcode. |

Listen |

Listen |

Requested file could not be found (error code 404). Verify the file URL specified in the shortcode. |

||||||

|

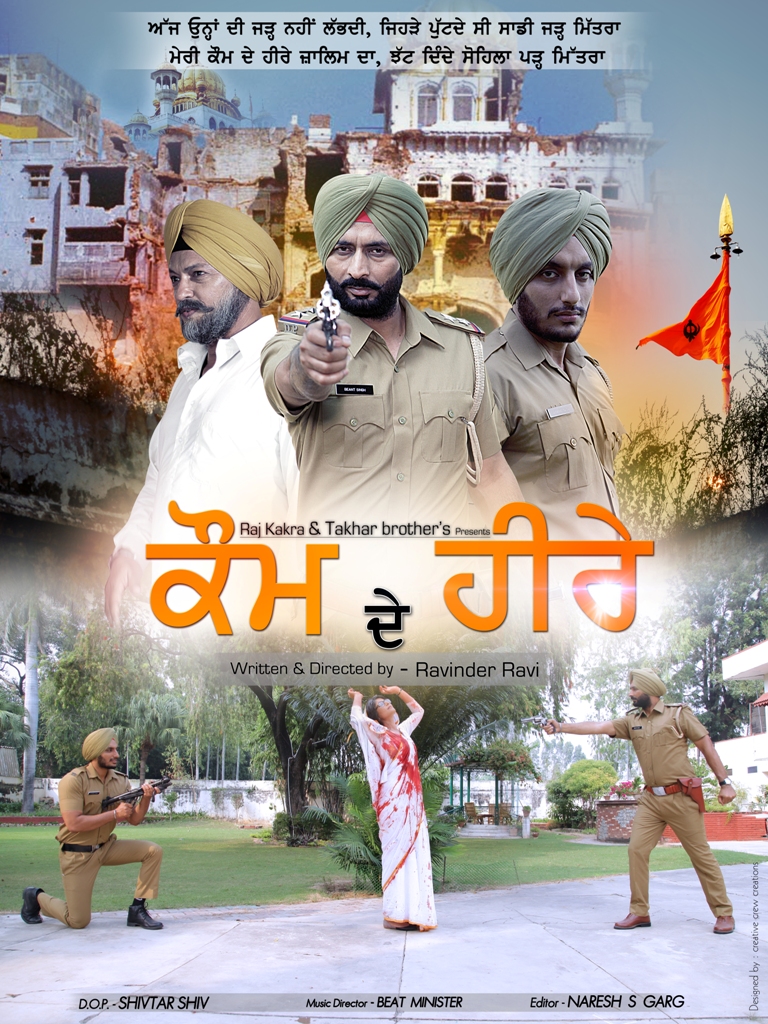

In a recent piece explaining the need for an initiative to defend free speech in India, I mentioned the case of the Punjabi film Kaum De Heere (Diamonds of the Community), based on the October 31 assassination of Indira Gandhi by two of her guards, who were devout Sikhs. I had written, “While the title of the film was provocative, it was also not far from the facts. In June 1984 Indira Gandhi had sent the Army into the Golden Temple complex, the holiest shrine of Sikhism. The two guards were not alone in their anger, and have been posthumously hailed as martyrs by the Sikh clergy at the same shrine.” The film, cleared by the censor board, was barred from release the night before the screening was to start in cinema halls across the country. Kaum De Heere

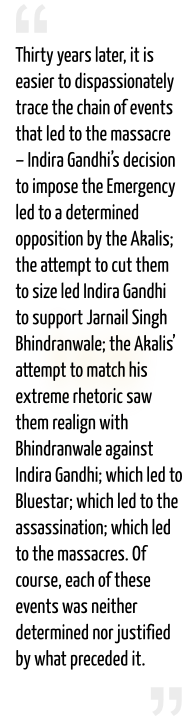

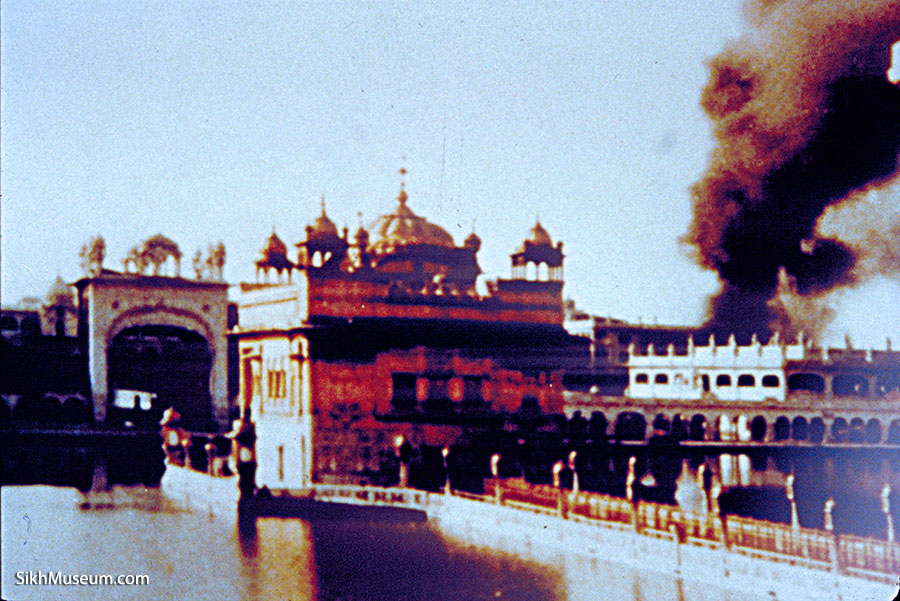

As we approach the 30th anniversary of the massacre of nearly 3000 Sikhs in Delhi, I think it is essential that people actually consider the premise suggested by the title of the film. The massacre is almost always invoked with Indira Gandhi’s assassination, as part of the chain of action and reaction that allowed Rajiv Gandhi to say “when a great tree falls, the earth shakes”. Thirty years later, it is easier to dispassionately trace the chain of events that led to the massacre – Indira Gandhi’s decision to impose the Emergency led to a determined opposition by the Akalis; the attempt to cut them to size led Indira Gandhi to support Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale; the Akalis’ attempt to match his extreme rhetoric saw them realign with Bhindranwale against Indira Gandhi; which led to Blue Star; which led to the assassination; which led to the massacres. Of course, each of these events was neither determined nor justified by what preceded it. For a large portion of the Sikh community, the tragedy of the massacre is made starker by what preceded the assassination, especially the scar inflicted by the ill-planned Operation Blue Star. It is necessary for others to understand, even if they may choose not to sympathise, the concerns that separate the views of a significant portion of a community from the rest of the country. This is where films such as Kaum De Heere come in. The ban was invoked after the censor board had cleared it. The reason cited for the ban was its potential impact on law and order, not the content. It would suggest that we are a nation where a point of view that might seem uncomfortable to many must not be expressed. But if we do not make an attempt to understand a point of view because it is a source of discomfort, how do we come to terms with events that actually happened, whose resonance is felt today? Operation Blue Star

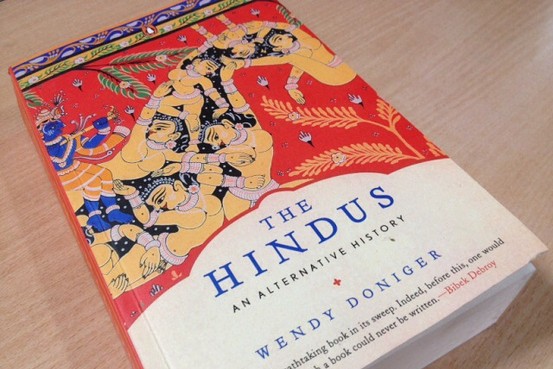

Misconceptions between communities will not disappear if we fail to face up to uncomfortable facts. Much of the recent history of friction between communities in India is the result of this failure of mutual understanding, the absence of any possibility of dialogue. This is evident from incidents ranging from a scuffle over a religious procession, to the demolition of the Babri Masjid. In a society like ours, where plurality is a given, not just in the country as a whole, but in most towns and villages of the country, the failure of such dialogue is tragic. Censorship, which is what the ban on the film really amounts to, is only a way of postponing the strife that discussion would temper. It allows rifts to grow as different versions of the past take root and grow. It is only if we allow people exposure to different views of the same event – views that may even seem unpleasant – that we can encourage a dialogue allowing for mutual understanding, even in the absence of mutual agreement. Traditional norms of tolerance, which allow different standards of behaviour within different communities, had been mediated by centuries of coexistence in a fixed setting. Given the mobility and urbanisation of our times, these norms no longer suffice. Today, it is a given that issues that divide communities will always fall under that convenient label that the Indian law and order machinery so easily invokes – ‘sensitive’. The very term then precludes possibilities of a public conversation. But consider what happens when the state does not intervene, as is the case with the recent film Haider. There are few topics as divisive as Kashmir in our country, but from the role of the Army to the question of disappearances, much that has never been part of widespread public conversation is now so because of the movie. Wendy Doniger’s The Hindus: An Alternate History –

A climate of censorship Or consider the case of the more prominent restrictions on books over the recent past – The Satanic Verses, Shivaji: Hindu King in Islamic India or Wendy Doniger’s The Hindus: An Alternate History. There is reasonable ground to argue that the consequences that followed from the publishing of Rushdie’s book were the result of Rajiv Gandhi’s opportunistic and unasked for decision to ban the book. The hooliganism of those opposing Laine’s was reduced to a whimper when the Supreme Court finally lifted the ban. In the case of Doniger’s book, it was widely available without any significant repercussions, before the publisher, Penguin India, capitulated in a craven manner. In each case, the dialogue that would have taken place in the public sphere, whether it was prompted by Islamic fundamentalists in case of The Satanic Verses, or by Hindu fundamentalists raging against Doniger, may have given us a chance to confront the streams of rhetoric that become ghettoised within communities. The case for censorship can muster little evidence; rather, the facts indicate that censorship eventually only furthers the strife that it seeks to avoid in the name of a hurt feeling or a perceived offence. Silence does not serve the cause of the plurality; discussion and engagement, however acerbic, do. In our republic, the need for a largely unfettered freedom of expression is not just driven by idealistic fervour, it is a pragmatic requirement for coexistence. |

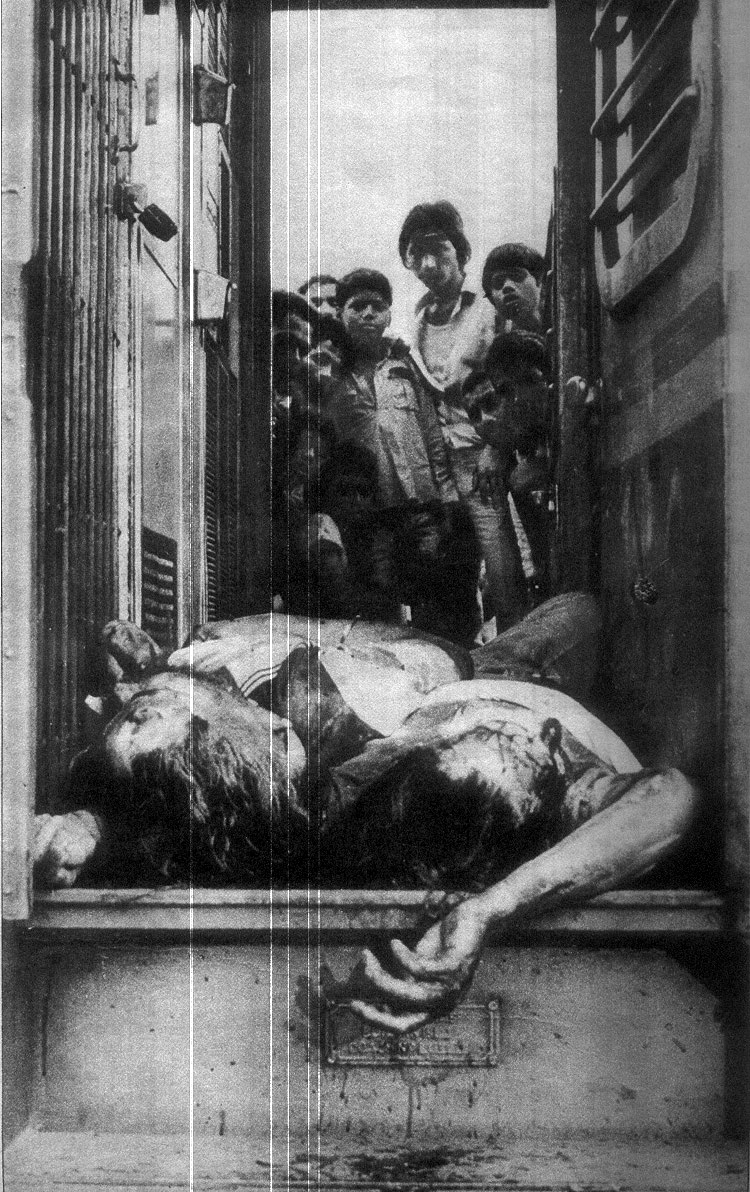

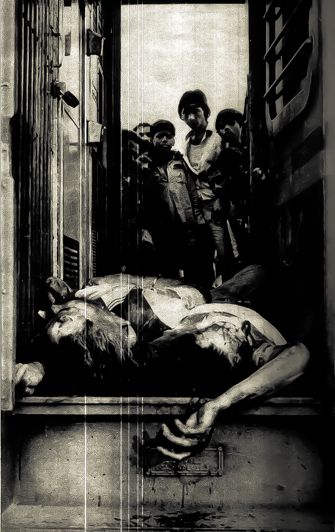

On October 31, 1984 politically motivated communal violence in India was catapulted to a whole new level in the aftermath of Indira Gandhi’s assassination by two Sikh bodyguards. The assassination kicked off an orgy of violence against Delhi’s Sikhs, going on for three whole days. By the time the dust had settled, 2733 men, women and children had been slaughtered, according to official estimates. The riots killed any lingering hope one might have had that the Prime Minister’s murder would signal an end to the burgeoning Sikh militancy in Punjab, in the same way Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination of 1948 shocked the nation out of its madness after Partition. As evidence has shown, the riots were instigated by certain members of Mrs Gandhi’s own party, the ruling party at the time, in a misplaced bid to exact revenge from an entire community, for the death of their beloved leader. Beyond the inevitable destruction and mayhem, all they ended up doing was radicalising an entire generation of Sikhs. The Sikh militancy received a major boost and large swathes of North India remained under its yoke for the better part of the next decade.

The riots may have lasted barely three days. Their after-burn, however, continues to linger thirty years later. Today, the story of 1984 is not the story of the assassination or the Khalistan cause that fizzled out in the mid-nineties. Today, 1984 lives through its victims; through the ageing widow who runs from pillar to post to get justice for a husband brutally murdered thirty years ago; through a generation of adult men and women forced to grow up without knowing a father; through the silent anger of an aggrieved people defeated by an intransigent justice system in their bid to get the guilty of the time placed behind bars… Today, 1984 is akin to a festering wound that continues to run, a rambling narrative that drones on without any sign of a fitting closure. It may be invisible but it is not forgotten. It cannot be. Far too many people sleep with anger as a result of it. This anger lends it the potential of returning in a frightening incarnation. Memories of terror

History is useful in explaining the past. It can tell us how and why tragedies such as the events of 1984 unfolded. It is useless, however, when it comes to putting the ghosts of such outrages to rest. We might have a voluminous history of fomenting communal violence. But we lack a similar legacy of repairing the social cleavages that such violence opens up. Our oft-repeated reaction to such events is silence. Part of that comes from political expediency. The Delhi riots of 1984, just like the Gujarat riots of 2002, were politically motivated. The political fraternity is understandably hesitant to prosecute itself. Furthermore, silence has its uses. Right after certain events occur, such as the riots of 1984, nerves are too fraught and memories far too raw for a constructive dialogue to take place. Hence, silence is necessary to give the inner ferment time to settle. With the passage of time, however, the silence begins to rankle. The continued absence of reflection and self-examination ensures that the hurt churns inside the body politic and keeps us divided as a people, while laying the groundwork for the next generation to grow up chock-full of the hatred and distrust that bedevilled their forefathers. The Hindu-Muslim riots that accompanied Partition took place more than sixty years ago. Their shadow continues to dog relations between the two communities to this day. The possibility of memorials

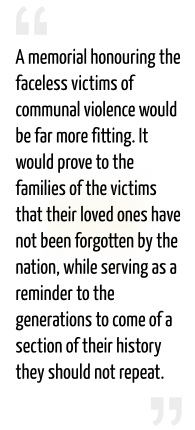

So, how do we put such events to rest? Punishment meted out to their perpetrators, however late, would be a start. But in the case of 1984 riots, many of the perpetrators are already dead. Other kinds of solutions must be found. A memorial honouring the faceless victims of communal violence would be far more fitting. It would prove to the families of the victims that their loved ones have not been forgotten by the nation, while serving as a reminder to the generations to come of a section of their history they should not repeat. Furthermore, it will give all communities a reason to unite behind something, since even the most parochial individual should have no issue with honouring the victims of violence. Such a memorial, however, will truly resonate with the body politic only if it is free from the rotten stench of politics. If it is appropriated by a political party or the other, then it will, invariably, bear the stain of a self-serving ideology, and become just another bone of contention. God knows we have enough of those already. Let the memorial be constructed by a non-governmental entity made up of committed individuals who come together with the sole purpose of building such a memorial. Once they have built it, they should leave its maintenance in the hands of an able group of administrators, and then disband. Moreover, it would be best if the money to construct the memorial was raised through small and large contributions from the people. Then only will it be a true people’s memorial. William Faulkner

The Nobel Prize-winning American writer William Faulkner once said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” When it comes to communal violence, we in India have lived that maxim to the letter. Now, let us make a break from it and put events such as the riots of 1984 where they truly belong. They deserve to be marked in a memorial that honours their dead rather than replayed in the streets.

|

||||||||

|

Hartosh Singh Bal is the political editor of The Caravan Magazine. As a journalist, he wrote for The Indian Express, Tehelka, Mail Today, and he was the political editor of OPEN Magazine. He is also the author of Waters Close Over Us: A Journey Along the Narmada (HarperCollins India, 2013) and the co-author of A Certain Ambiguity: A Mathematical Novel (with Gaurav Suri; Princeton University Press, 2007). He is a trained engineer and mathematician.

|

Vikram Kapur is Associate Professor of English at Shiv Nadar University, Greater Noida. Educated in English and Mass Communication from the US, he received his Ph.D in creative and critical writing from the University of East Anglia, UK. He taught journalism and creative writing in both countries. He wrote two novels, Time is a Fire (Srishti, 2002) and The Wages of Life (Srishti, 2002). He has published numerous short stories, and has authored many articles for various newspapers and magazines in the US and India. Details available here.

|

||||||||

Disclaimers: The opinions expressed by the writers are their own. They do not represent their institutions’ view.

LILA Inter-actions will not be responsible for the views presented.

The images and the videos used are only intended to provide multiple perspectives on the fields under discussion.

Images and videos courtesy: Photos of the Week | Sikhsiyasat | Angry Brown Girl | Quotes Pictures | Sikhsiyasat | Sikh Museum | Hindu Human Rights

Voice courtesy: Samuel Buchoul

Share this debate… |

… follow LILA… |

||||