|

9 January 2015

What means, today, a home? No one, anymore, is really safe from the experience of the departure, of expatriation or of the diaspora, out of necessity, or, if the distinction is not yet fully blurred, out of one’s will. Where else to say this than in India, home or origin for one of the world’s widest and most successful diaspora? Translocality has been realised and kept alive by the multiplicity of cultures in India for centuries, where the movement of an individual, of a family, of a community, can be wisely understood as a wager on the future – diaspora, or when space can open to time. 9 January 2015 is the centenary of a return, that of Gandhi from South Africa, yet the Indian Government has made of this ‘Pravasi Bharatiya Divas’ a day of recognition for all those who left their motherland. The inclusive symbol is strong: Indian origins would still be Indianness, even when distance, in the miles and the years, looks like it could possibly mean only oblivion and separation. Or is it yet another story, inventing this sense of an extraordinary cultural faithfulness to dissimulate the economic and financial dependency on this diaspora, which had not found the necessary opportunities at home? For this dialogue on the translocal, T.P. Sreenivasan connects the numerous dots of cultural and inter-cultural victories, to discover the positive role of the Indian diaspora in the strengthening of diplomacy and geopolitics. Meena Alexander engages the introspective journey to visualise the many moving landscapes and translations that have come to make of her a migrant writer.

Debate

Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations.

|

|

All major nations, particularly those which have contributed to the migrant population around the world, have a diaspora policy, which has assumed the dimensions of diaspora diplomacy in the recent past. India is no exception.

Initially, India had taken the position that Indian migrants should owe their loyalty to the countries of their adoption. But India would remain alive to their welfare and interests. Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi was the one who hit upon the idea of seeking investment, scientific knowledge and human resource from the Indian communities abroad.

In return, Rajiv Gandhi pledged support for them, in the event of any problems. The coup in Fiji was the first occasion when India openly protested against discrimination shown to Indians. India imposed trade sanctions against Fiji, took up the issue at the UN and got Fiji expelled from the Commonwealth. Earlier, India merely accepted the returnees and resettled them. India has now made it clear that it will stand by its diaspora at all times. India has also elaborated its diaspora diplomacy, which includes various concessions to enable them to enter India, own properties here and enjoy almost all the privileges of its citizens, except voting rights.

On the side of the diaspora, there have been several measures to develop and strengthen India, such as remittances, investments and even return of technical personnel. More importantly, the Indian communities in countries like the US and the UK began influencing their Governments in favour of India, like in the case of the India-US nuclear deal. In the US, the India Caucus in the House of Representatives and the Friends of India in the US Senate are essentially creations of the Indian diaspora. India’s diaspora policy enjoys consensus among all the political parties in India.

Signing the India-US nuclear deal

The Indian diaspora consists of people who left India on their own in search of promised lands. India neither encouraged nor discouraged them. But now that there are about 30 million of them in different parts of the globe, India had to develop regulations to assist them and also enter into agreements with host countries to protect their interests. The presence of the diaspora began to have a bearing on the bilateral relations with the countries concerned. There is recognition today that the contribution of the diaspora has a positive impact on these relations and that good relations between the two countries will be beneficial to the diaspora. The Government and the diaspora have, therefore, a mutual interest in promoting good relations with the host countries.

The case of the Indians in the Gulf illustrates this point. It was merely a matter of demand and supply when Indian workers began to go to the Gulf. Though we had historical links with the Gulf, India and the Gulf were focused on the West and not on each other. The difficulties that arose were on account of unscrupulous agents misleading the job seekers and not because of any prejudices against the Indians. Indian workers have a fairly positive image in the Gulf. But it is inevitable that these countries would like to replace foreign workers with their own. The present trend of unskilled and semi-skilled Indian workers being replaced by white-collar workers and executives will ensure that the total number of Indians in the Gulf will not decrease in a hurry.

Another way to ensure continuation of the Indian populations abroad is to develop our relationship with those countries in such a way that those countries have a stake in India’s development. India’s growth and its ability to assist these countries with trade and security matters will deepen their relations with India. Considering the history of our relations with the Gulf, cooperation in such areas is logical, because the countries have cordial relations.

Indian diaspora in the Gulf:

Opportunities for cooperations

Diaspora diplomacy was not an important factor in Indian foreign policy till recently. Our strengths in the initial stages were India’s cultural heritage, the nature of our freedom struggle through non-violence, our democracy and the global leadership we gave in non-alignment, disarmament, equitable economic development and human rights. India’s idealistic approach to foreign policy was widely admired. Subsequently, India’s low growth and alleged closeness towards the Soviet Union became challenges, but after the end of the cold war and India’s economic liberalisation and significant growth, India returned to its prominent position in the world. India’s soft power, our cultural heritage, Bollywood and the diaspora skills won us extra points during the various stages of our development.

Our diaspora diplomacy, including our declared activism in the event of any problems for Indians abroad has not hurt our foreign policy in any way. There is worldwide recognition that the sending state has the responsibility to protect their people. In any event, our support is conditional to their being innocent. We expect the diaspora to obey local laws and we do not intervene unless the cases are genuine. We also have not bent our foreign policy in order to expand the diaspora. The policy is more regulatory than promotional. The economic dynamic of the diaspora does not in any way put pressure on us to change our international stance. If anything, India’s stock has only risen in the international community on account of the principled support we extend to the diaspora. Even in Fiji, though the indigenous Fijians were initially surprised at India’s sanctions, they felt later that Fiji would not have returned to democracy, had it not been for our position. The present elected Government in Fiji has significant support among the Fiji Indians as it was elected on a common roll without any weightage to any of the races.

India’s links with the diaspora have grown in the recent years, because the Government of India and the Indians abroad have rediscovered each other from the days of Rajiv Gandhi. Today, the diaspora is anxious to participate in the economic development of India as they feel that they should repay in some way for the sense of protection the Government has given them. Institutional arrangements like the Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs (MOIA) and the annual Pravasi Bharatiya Divas will also play a catalytic role. India-Diaspora relations are certainly in a win-win situation for both sides today.

|

I have travelled right from childhood. After the Bandung conference, my father was posted by the Indian government to Sudan. I turned five on the Indian Ocean. I have written poems about this experience, including ‘Water Crossing’ which appeared in my most recent book of poems Birthplace with Buried Stones (2013) and a long poem called ‘Indian Ocean Blues’ which will appear in the forthcoming book Atmospheric Embroidery (2015.) I feel that this experience of early crossing has marked me deeply and I keep returning to it in my imagination. A space of fluid borders where one world has vanished and another has not yet come into being. Perhaps it is for this reason that in New York City, where I live, I often write on the subways and in buses; I also write in transit lounges and in planes. It is possible to do this with the crafting of poems since it is an art of small lines and images, etching on a tiny tablet of ivory as it were. Rather than the large canvas that a novel needs.

A ship arrives in Port Sudan

I turned five on the steamer as my mother and I traveled from Bombay to Port Sudan, to meet my father. I still think that having my birthday on the deep waters of the Indian Ocean has marked me in ways utterly beyond my ken. It has left me with the sense that home is always a little bit beyond the realm of the possible, and that a real place in which to be, though continually longed for, can never be reached. It stands brightly lit at the edge of vanishing. I think of Mallarmé who evoked the image of l’absente de tous bouquets, the quintessential flower absent from all bouquets. For me, that is what home is. And our migrations become the music, wave after wave of it, that gives it a fragile and precarious shape.

Can one find a home in language? I feel so. At least, that is what I have tried to do. I left India too young to attain literacy in my mother tongue, Malayalam, a great Dravidian language with proud traditions of literary culture. I speak it fluently and the rise and pour of that language have shaped the kind of poet I am. I learnt Hindi as a child, and as I grew older, English took its place in my mind, and became for me a language of crossing and of delivery.

The English I use bends and flows to many other languages. For me, it is the language of Donne and Wordsworth as well as a postcolonial tongue, and it exerts an intimate violence, even as I use it, make it mine. Yet surely each language, each script, exerts its pressure. It seems to me that a poet works with words as a painter works with colour – as matter, she cannot do without, this living material into which she must translate what would otherwise remain inchoate.

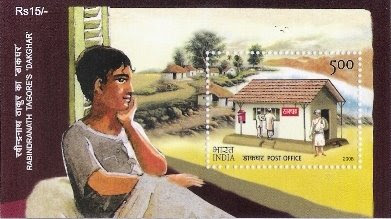

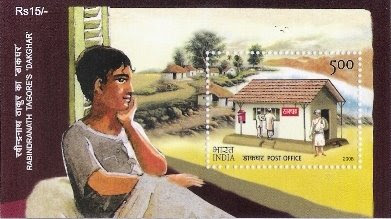

My earliest poems, which I wrote at the ages of ten and eleven, were composed in French. It seemed to me, after having been made to learn a few lines by Verlaine, by heart in school – I refer to Unity High School in Khartoum, Sudan – that French was surely the only language fit for the lyric. Mercifully, none of my earliest French poems survived. Soon enough, my affections shifted and I found in English a more capacious instrument for my longing. But those earliest longings, as they found expression in poetry, were flattened out, imitations of Toru Dutt and Sarojini Naidu, cut and pasted as it were, onto white paper. Indeed, I found in those early Indian women composers of poetry in English something of the circuitry of sense that a colonial childhood had instilled in me. And there was Verlaine, whose subdued, yet febrile lines, spoke very directly to me. And Rabindranath Tagore, whose poems in English translation from Gitanjali, The Gardener and Fireflies, I was reading. But it was the play The Post Office, telling as it did of the death of a young boy, that haunted me, and indeed haunts me still. Someday, I said to myself, I will make a poem and evoke the way in which, as children in India, my cousins and I put on the play for our immediate family. A Bengali play, translated into English and acted out in the courtyard of a Kerala house, in the constant presence of Malayalam, our mother tongue. Yet we spoke the words in Tagore’s own English translation, in our lisping Indian English.

Tagore’s The Post Office

All this was in India, but also in the Sudan where I spent a good part of each year, in the north of the country where the language was Arabic. As a teenager, I had a group of poet friends who wrote in Arabic, while my friends who translated a few of my English poems and submitted them to the local newspaper. My very first publications were in Arabic, the language of the place in which I lived, but a language that I could not read or write, though I could indeed speak it with a certain fluency. People would come up to me and say “I saw your poem in the newspaper”. And then add something like “I really liked it” or “I didn’t really get it. What was it about?” All I could do was shake my head and smile wistfully, making it clear that while I read and wrote English, I could not lay claim to the same talent in Arabic. So, my life as a poet began in translation, and that connection to a reading public alone could allow me a ‘real’ existence. It was that a translated life, held sway.

Poetry and place are bound up together. If poetry is the music of survival, place is the instrument on which that music is played, the gourd, the strings, the fret. I have sensed the truth of this, but certain difficulties befell me. To be a real writer – and I underlined the word real in red ink, in my own head – it seemed to me that I had to have grown up in one place, “one dear perpetual place.” Even if I did not have Yeats’ poignant phrase in mind, what I had was a vivid sense that every great writer I knew had a language each, and a place to which he or she was wedded. And the language bubbled out of place as water from underground streams the earth concealed. In this way, it was an outcrop of the region, desha-bhasha.

There was Kumaran Asan, who lived in Kerala and wrote in Malayalam; Tagore, who lived in Santiniketan and wrote in Bengali; Verlaine, who lived in France and wrote in French; Shakespeare, who wrote in English and lived somewhere in England, that tiny island floating on a map that I had seen several times in school but could never quite make head or tail of. Lacking just one single place to call my home and shorn of a single language I could take to be mine, and mine alone, I felt stranded in the multiplicity that marked my life. Its rich coruscating depths drew me, or so I felt, into grave danger. It took me quite a while to realise that I did not have to feel strung out and lost in the swarm of syllables. Rather, the hive of language could allow me to make a strange and sweet honey, the pickings of dislocation. I also understood dimly that I was not alone in this predicament, and that I could gain a great freedom and indeed find sustenance for my art by flowing as well as I could into the sea of migrant memory.

|

|

T.P. Sreenivasan is the Vice-Chairman and Executive Head of the Kerala State Higher Education Council, after a career of 37 years in the Indian Foreign Service. He is the former Permanent Representative of India to the United Nations, Vienna and Governor for India of the International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, and Ambassador to Austria and Slovenia (2000-2004), with previous postings around the world. He is the author of several books, and a regular commentator on politics and international relations in national and regional publications in Kerala.

|

|

Meena Alexander is an internationally acclaimed author and Distinguished Professor of English at Hunter College and at the CUNY Graduate Center, New York. Her works span over genres, combining over a dozen of publications in poetry, essay, autobiography (the praised Fault Lines, 1993), novel and literary criticism. She is the recipient of numerous awards, including the PEN/Open Book Award in 2002 for Illiterate Heart. Her latest book is Birthplace with Buried Stones (TriQuarterly Books/ Northwestern University Press, 2013).

|

|