We often hear laments about the loss of our old way of life because of the rate at which technology has come into our lives. Looking closely, one would see that this sense of losing a life that was less dependent on technology is independent of the new technology interfaces themselves. The way technological platforms and tools are promoted also cannot be held responsible for this feeling of loss. The fact that something exists, does not mean that it must become a part of our lives in a consuming way. It is one’s choice to use or not use, or how much to use of, an available technology. If one has difficulty in making a choice in this regard, due to any reason, that predicament should not be blamed on technology.

Now, let us consider the anti-technology line that, as humans, we should distance ourselves from technology because it is unnatural. I hold this argument deeply flawed, and propose to investigate it briefly in this essay.

The lack of willful and explicit choices being made with regard to technology and the latest platforms and tools, is one of the fundamental problems that we face today. Development and proliferation of technology is a naturalistic process. From time immemorial, humans, as thinking beings, have understood the need to discover ways and means to bring ease and speed to life, and have built technological devices towards that. With the passage of time, and evolution of the notion of capital, this process got accelerated in a synthetic manner. And, this acceleration happens when there are already signs of a traction building up. This means that technology itself and the capitalistic applications of it are two different things.

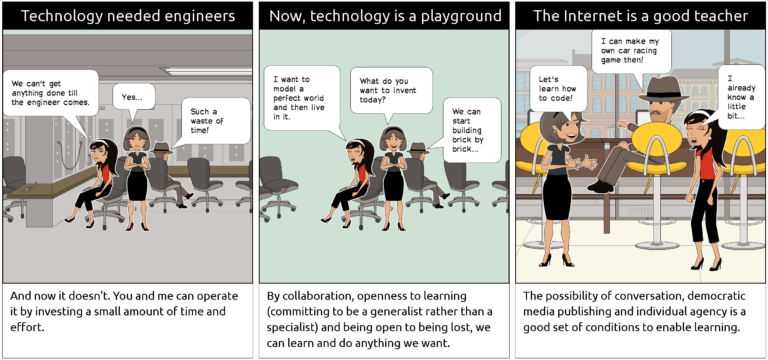

At no point in history has technology been so mature and offered us a potential to leapfrog the limitations of being human. It is high time we accepted that we have to make a conscious choice on this count, instead of claiming our engagement with technology as an involuntary and unwilling action, which we have no control over. In this context, the lack of a counter-thought process is glaring in its absence. We need a discourse that puts the ‘other’ (here, ‘technology’) in the centrality of our focus.

We cannot wish for a different world and at the same time be a consumer of the same system that we are critiquing. Functions and utilities cannot be argued from a philosophical perspective; they have to be countered by alternative functions and utilities only. The Do-It-Yourself (DIY) ethic was, in the beginning, an effort to break away from the consumer role by becoming a producer oneself. But, this was quickly appropriated by the market (IKEA, modular architecture etc.). The Internet has seen a similar transition – the interest in open source has moved from a consumer space to a professional space. Today, subscription-based web services and the cloud are offered to us as an easy-to-use alternative.

The lack of a viable alternative is the gap that we must talk about urgently. On the one hand, the cyborg imagination and Artificial Intelligence are the reigning fantasies, and on the other, we have a vacuum. It does not take much intelligence to know what is troubling for the humanistic process, but it takes some genius to even propose viable alternatives. One of the paradoxes that we encounter here is that the development of such alternatives will require the use of the same technologies that are being understood and propagated as problematic. And there is naturally a hesitation in using these.

That, an existing set of tools has to be used for the development of a new set of tools, has made the pro-tech/anti-tech war an evidently lopsided one. For instance, the huge social costs we are currently paying because of the dominance of social media have not been successfully negotiated by any of the communities voicing out their reservations against the phenomenon.

An organic engagement with technology would entail an imagination, articulation and manifestation of possibilities for a fuller and balanced adoption of technology. One positive aspect of the technophilic culture is the assumption of the responsibility to work on the ideas that one imagines. This means that the cultures of technology are constantly iterating on imagination, desire and capacity leading to a very rapid cycle of innovation. For instance, the Internet and the open source software movement have co-evolved across the last two decades and the movement today offers us a viable way of conducting our everyday exchange of data and trade. There are platforms for free trade which can be accessed by small and big producers equally (eBay, Amazon, Flipkart); there are platforms that allow small operations to work in a decentralised and remote manner (Slack, Skype, Email); there are platforms that let the creation of documents in a collaborative and transparent manner (Wikipedia).

This is not to say that the technological ecosystem is ideal and free of disparities and inconsistencies. The only thing that is said here is that the problems inherent in the current structures of technology can only be solved by a mass-participation and interest in the production of counter-technology, an alternative means to take care of the functions that technology fulfils today.