LILA: The Kugali Anthology of best African stories is a crowd-funded project – the first of its kind. How did the concept take shape to create an independent platform involving artists from the international diaspora?

Kugali:Wow, I don’t know how to say this in just a few sentences. You’ve just asked me for the story of Kugali’s evolution as a company. We started out as a podcast that searched for the best African stories in gaming, animation, TV and comics and told the world about them. We added a blog, YouTube channel and eventually a website that was basically a wiki or database for all this content. That website has long since been changed to focus on just our own offerings. We eventually started putting out Kugali Magazines, which were monthly publications that featured three comics along with interviews with the comic creators. It wasn’t hard to get a few creators to agree to this, as we had already been interviewing creators and promoting their work for free for over a year. The Anthologies are basically bigger versions of the Magazines. Thrice as big. As a small startup, we needed crowdfunding to achieve this dream. We’re constantly looking for ways to help people discover these stories, because that was how we started. We wondered whether anyone in Africa was doing anything as good as the things we had grown up watching, reading, playing and if so, why hadn’t we heard about them? We’re launching the Kugali Comic Club soon, an online subscription service that delivers new digital comics every week to reach those people who can’t order physical books.

LILA: African literature portrays an extensive blend of colourful beliefs, superstitions, practices, myths, hearsays, and tales. Do you differentiate based on their contemporary appeal and usability or use every component boldly?

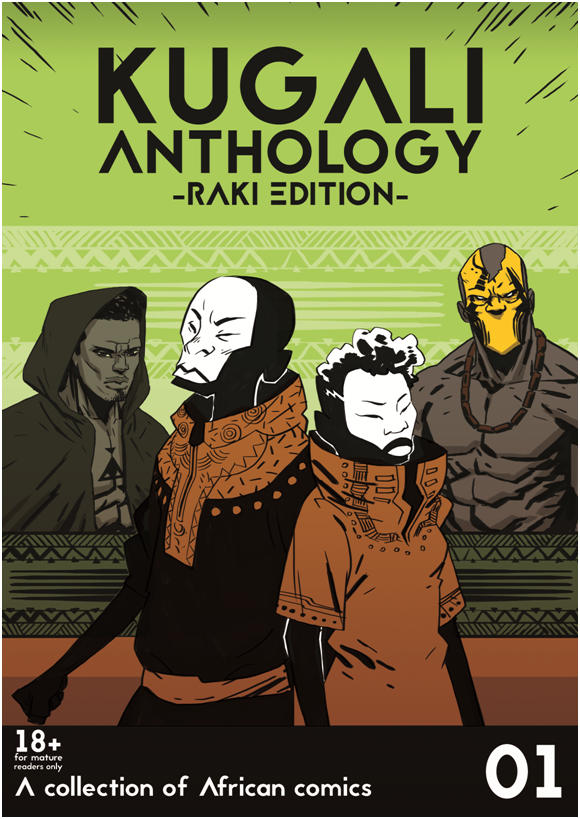

Kugali: Not all of these beliefs, superstitions and myths are suitable to be used in Children’s stories, so anything we think will make parents of young children uncomfortable goes into the Raki edition of our Anthologies. The Raki editions are the no holds barred comics where we let the creators put in whatever they want. It could be gory, it could have sexual content, it could ask difficult questions or it could contain spiritual beliefs that are contrary to the most widespread religions of our time. The Standard edition Anthologies contain stories that are family friendly. There is no overlap between the stories featured in both editions. They are completely separate comics.

LILA: Some African words are more common today and have a familiar warmth about them even to outsiders. Do you use/ plan to use terms that relate to a specific topic or idea from your rich languages to establish a stronger connection with ‘Mother Africa’?

Kugali: Having lived all my life in Nigeria, I’m not aware of any Nigerian terms that people outside Africa would be familiar with except “jollof” and “juju”. I know most other African countries know a lot of our terms because Nigerian music, movies and now comics are almost ubiquitous across the continent. In our comics, characters speak exactly as people from whatever region the story is set in would actually speak. So in a Nigerian comic, for example, you would get a mixture of English, pidgin English and whatever language is spoken in a specific locale. Just as anime fans worldwide have become familiar with many Japanese phrases just by encountering them regularly in anime, we wish for readers to become acquainted with our unadulterated lingo.

LILA: Is there any particular practice that is on the verge of oblivion now, but you would like it to survive, even in a change of form? Have you used anything similar in your stories?

Kugali: The only thing that comes to mind is the fact that most educated children of upper class and upper middle class parents can barely speak the languages their parents are fluent in. Many of us start our education in Nigeria and finish it somewhere in the Western World. Even I, who schooled entirely in Nigeria, was taught completely in English. So in my formative years, no one spoke Yoruba to me, even though the adults around me spoke it to each other. I understand basic phrases now, but I can’t speak it fluently. When we get to the point where we can make animated shows and movies, I’d love some of them to be entirely in the creator’s local language, and people have to watch it with subtitles, just like most anime fans prefer to watch their anime in Japanese and read the subtitles. When your language becomes “cool”, it’s easier to get kids to learn it.

LILA: How have the main set of practices or beliefs taken shape in the next generations who are outside Africa as birth citizens or young migrants, and how do you connect as they are probably the most significant part of your readership?

Kugali: Funnily enough, people of African descent are not the largest demographic of our audience. Different people have different practices and beliefs, and I can’t tell to what extent the children of African migrants adhere to their parents practices. To begin with, culture is fluid and even in our home countries, some of us continue with our parent’s traditions while some of us choose our own practices. Migrants anywhere in the world have usually been ashamed of their own heritage and tried to conform to the norm of the country they have moved to, however, there has been a huge global paradigm shift in recent years such that it is now cool to proudly wear your cultural heritage. Admittedly, this has made it easier for us to connect with Africans born and bred outside of the continent, as well as young migrants. Perhaps, to an extent, they have a romanticised view of “The Motherland” and our work helps to reinforce that view, but that is what Kung Fu movies, buddy cop movies and telenovellas have been doing for China, America and India respectively, so it is not a bad thing in itself. Like we say at Kugali, “Stories shape our society, so let’s shape our stories.”

LILA: What are the cultural differences you can spot based on different ecolinguistics while working together and how do you deal with them?

Kugali: This hasn’t affected our workflow at all. Everyone speaks English for work purposes. We have a Facebook community where we can discuss arts and culture generally, and that’s where the cultural differences can shine through. Once in a while, a creator from one country may need to confirm the pronunciation of a word or fact check a story he heard about another country’s people, and he or she would ask the community.

LILA: The storyline of ‘Monkey Meat’ effortlessly highlights the insignificance of human life where the apocalypse is said to have been set by an emperor who may have just “pushed the button” as an aftermath of a fight with one of his 3,000+ wives! However, in many other stories also, dark humour is placed with a futuristic approach. It might seem like an escapist treatment – a privileged choice as an artist not to deal directly with the contemporary society. Was it an intentional treatment?

Kugali: Most of our stories are from completely independent teams who didn’t know about each other until they became a part of our community. We don’t give anyone any specific guidelines and ask them to create something for us, so the similarities are purely coincidental. Maybe it also says something about us, because we handpick only the stories that align with our vision to tell authentic African stories. We don’t want people to read a story and immediately see it as popular comic they already know but with African characters. You would notice we hardly have any superhero stories, because the very concept of superheroes is not African. Heroes are universal, but the secret identity, spandex and capes tropes is particularly American.

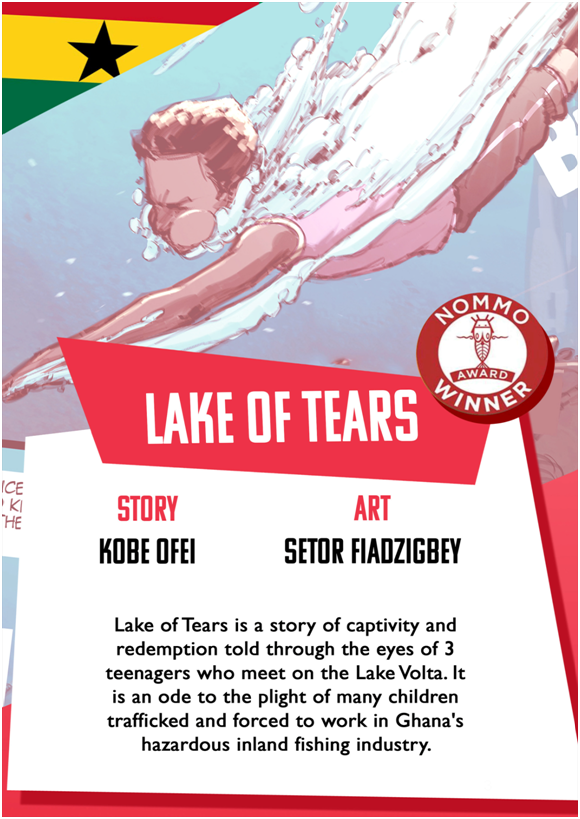

LILA: Do you plan to specifically work with more volatile social issues in future like you’ve done in ‘Lake of Tears’?

Kugali: We don’t have a specific mission to tackle social issues, neither do we wish to ignore them. We just want to tell the best authentic African stories that we can. As kids, when we fell in love with Samurai X, Voltron or Spiderman, it wasn’t because we could relate deeply to the stories, the ethnicity of the characters or any social issues. It was simply because we thought they were awesome. This didn’t stop them from tackling social issues when they wanted to. Samurai X talked about child soldiers in some of the stories and Spiderman always had social life and responsibility issues to worry about. There’s nothing inherently Japanese about a giant robot made of five robot lions defending the universe from intergalactic robeasts.

LILA: The augmented reality book sounds like a brilliant presentation. Tell us something about how it works?

Kugali: When someone installs our app, they can bring the actual characters into their homes and interact with them as the story is told. We wanted to add a layer of interaction that would make people move while experiencing the story instead of just staring at a screen. An example would be the way Pokemon Go made people walk a lot more to find rare pokemon. You’re not watching the story on your phone screen. Your phone screen is simply a point of focus that allows you to see the magical worlds of the creatures all around your home and a controller to help you interact with them. Magic will be real for the children who experience these stories.

LILA: Raki edition is separately done for a more mature set of readers. Is there any specific reason to choose the ‘comic’ form over the ‘graphic’ form of story-telling for this edition as well?

Kugali: The Raki edition was born when we asked ourselves whether we wanted our brand to be strictly child friendly. We unanimously decided that we didn’t want to place any limitations on any of our creators. We want people to tell the stories they want to tell, the way they want to tell it. So we had to make it easy for parents to know which stories were suitable for kids and which were not.