LILA: Some of your most extensive engagements have been with the Dalit community. Whether it is your photo essay on the denial of social justice, or your work with and for the ‘manual scavengers’ in Mumbai, you have brought a palpable sense of their lived experiences and struggles to public attention. You mentioned that your entry into the manual scavenger community was by complete accident. Can you tell us about how you came to develop a relationship with the community that allowed you to enter their space and capture their stories?

Sudharak Olwe: I come from a background where my grandparents were Hindus but from the lowest caste, usually referred to as Dalits. They converted to Buddhism around 1956. So, Ambedkar’s influence was always around us while growing up. When the ideas of Ambedkar come into your lives, an assertion and understanding of caste and its divisiveness also come in. We realised that for the last 2000-2500 years there has been continuous discrimination against Dalits, and that education alone would change this situation. My father was a poet and the first generation in our family to get an education. I tried to do Engineering but couldn’t, and then went into Fine Arts. I would say, as my family had already crossed a threshold, and also because I am from Mumbai, which is more of a cosmopolitan city, I never had to experience any grave atrocities and never knew of the situation in the villages. I had read enough to know what was still happening in the villages, but it did not affect as much. But my career as a news photographer spanning over 15 years, gave me an understanding on a range of issues like caste discrimination, rural politics, commercial sex workers, urban infrastructure and so on. Meeting people, interacting with them and learning filled the gap. I was processing all these within me and understanding how the society works, in what forms divisions exist, the problems women face, etc. When I was with the Times of India, I was photographing mostly film stars and businessmen, going to their houses and their parties and seeing them. But I soon realised this was not what I wanted to do. At the same time, people started coming to me saying that the road outside their house was in a bad condition or they did not have water connections and asking if I could take pictures and publish that in the newspapers. Thus, I started doing a lot of that. During those days, an acquaintance requested me to come along with him and see the working and living conditions of conservancy workers. When I went to their colony for the first time, I realised they were my own people; they were all Dalits. Many from the same village, from the same community.

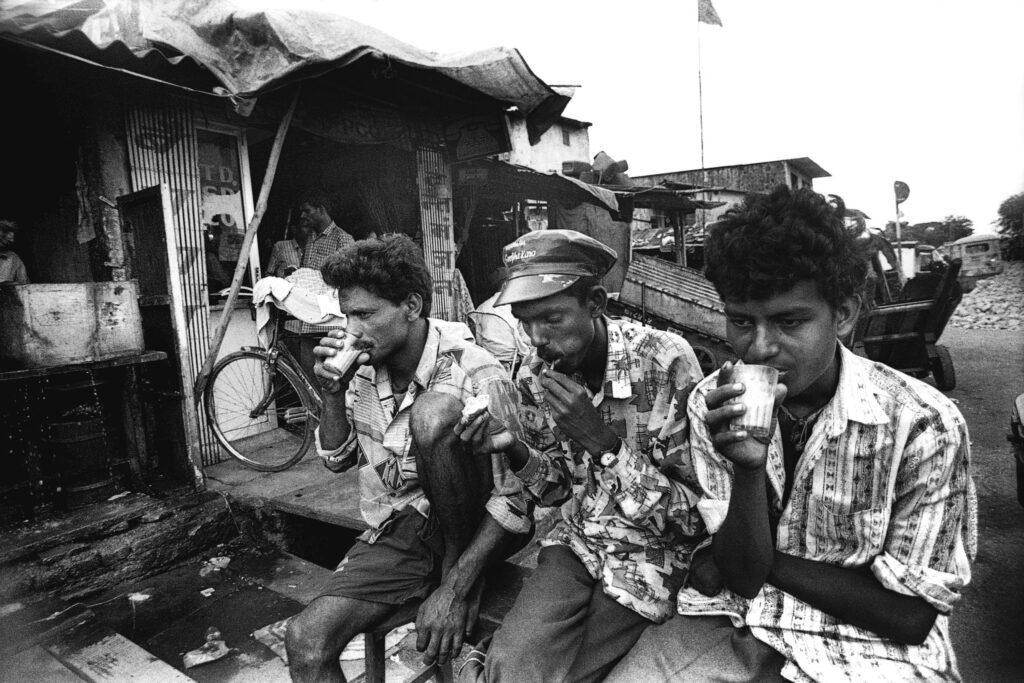

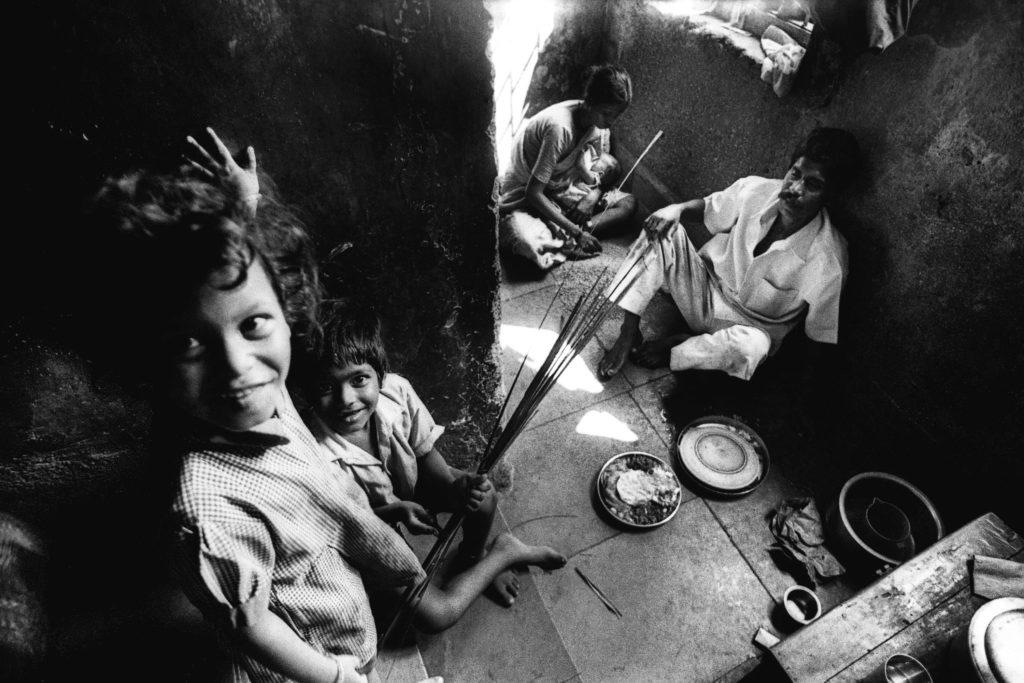

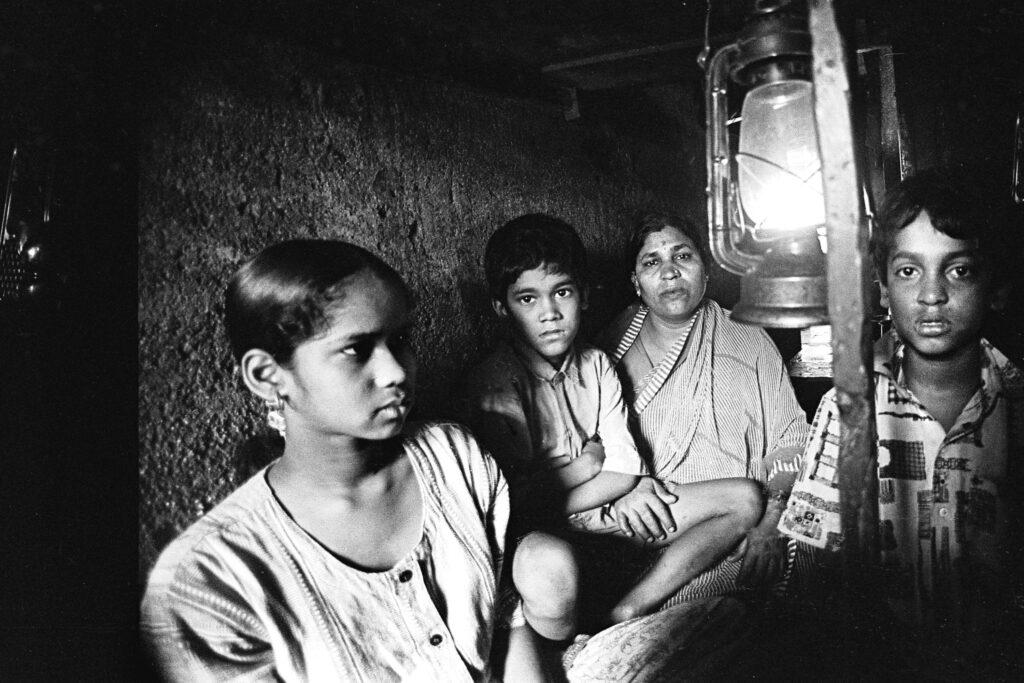

For the next one year, I went to meet them regularly, to listen to their stories and get a deeper understanding of their lives. They were doing such important work for the society, but their life had only misery and sadness. Their houses were in very bad conditions, the workers’ health was precarious. They would get up at 5 am and finish their work by 7-8 am. When the city wakes up, nobody gets to see these people. I have asked many whether they knew who cleaned the city, and the answer has often been ‘No’.

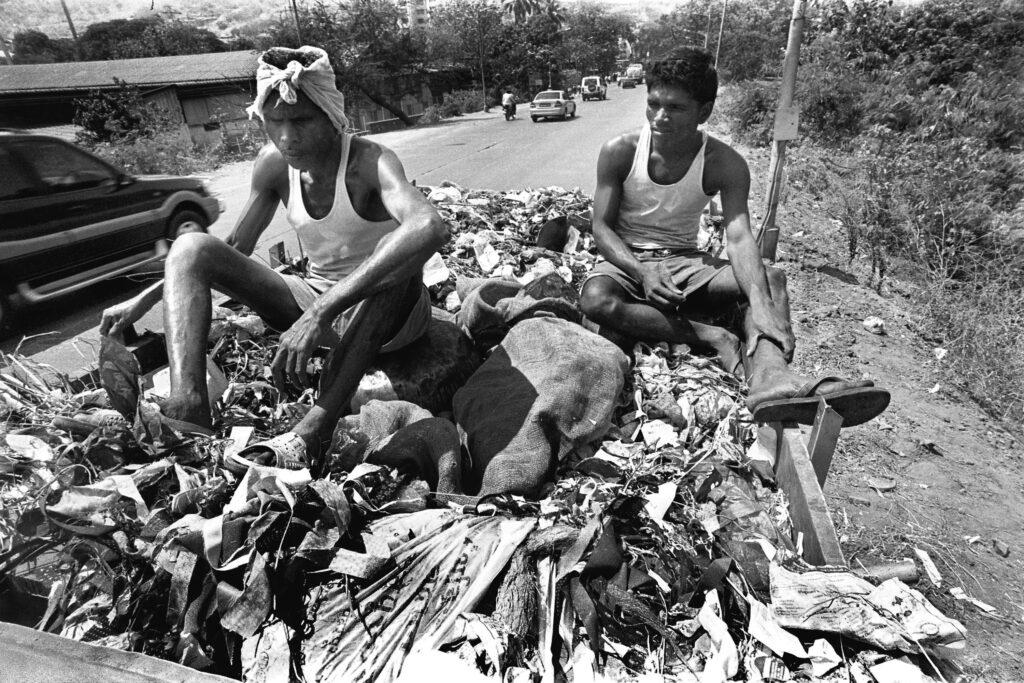

So, I started photographing them. They would tell me, nothing would change, and I would say, let me at least try. In 50 years, hardly anybody had seen their images in the newspapers. Reports about their deaths used to appear in some small corner of the newspaper and these were hardly spoken about by anyone. The Bombay Municipal Corporation has a huge trade union with influential people, but nobody had done anything for them because of their caste. These workers come from the lowest caste, and they don’t even have the right to ask any questions. A conservancy worker is the last step in the long hierarchy of the organisation, everyone above them will tell them what to do, but they do nothing to bring about some kind of change in their working conditions. The discrimination for the lower caste is so ingrained in the society still, that they are treated as second class citizens. They receive the worst kind of equipment. Though those are meant for their safety, the quality is so bad that if anyone uses them, he’ll surely die. So, it is actually safer for them to go without all the gear, and clean the sewage drains with their bare hands. I started taking pictures of them and their work, but I didn’t know what to do with them. Eventually I started exhibiting these images, and people were surprised to see the conditions in which these people were working. Many of them even denied it. When I told them, I had taken the pictures myself, they would say, “the city isn’t like this.” I would tell them, “You create garbage every day and have no civic sense. But person cleans it up for you because he is a Dalit and has no other way to earn a living.” Such dialogues started through these exhibitions, and I began to exhibit more frequently.

A decade later, the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan started. It was a very good initiative, but it did not look at the workers’ condition and the root cause of their misery – casteism. We all saw the Prime Minister washing the workers’ feet, but that was a pitiful thing, as if cleaning a worker’s feet would clean the entire country. Respect for the workers will start once we pay them and respect them as they should be. They don’t need sympathy. We need solid transformation and a complete shift in attitude to change the conditions of these workers.

We produce unbelievable amounts of garbage. Bombay produces 11,000-12,000 tonnes of garbage every day. It is the same case with most other cities, like Delhi, Hyderabad, etc. It’s the same people in the same working condition. They pick up dead cows and dogs with their bare hands, and nobody says anything about it. These images were a way to show the people what was really happening. I never knew what would happen with these images, but something came out of it. Ratan Tata saw these images and requested the Tata Trusts to engage with the workers. They released funds for new equipment, and the campaigns for workers’ dignity started. This is a very small step. The society at large has to change and own up to its past mistakes. Each citizen has to make it a point not to litter, and request anyone who is littering, not to. We need behavioural changes, even though there is a law against littering, not a single punitive action is taken. Because of all of this garbage, the large under-ground sewage pipes are blocked, many of which are decades old. And then this worker steps into the hole to clear the sewage and many of them die. No one is bothered; even the contractors just vanish.

The people who are giving you entry into their houses and giving you permission to take their photographs are the most important people. So the first thing is to ensure a sense of dignity at all levels. You come into their lives, understand them, and then you visualise and bring it out in your photographs. Talking is very important in this process, to build trust. Even the smallest things matter here. For instance, if somebody has offered you a glass of water in their house, and you haven’t even touched it, you have already disconnected from them. They know you’re not drinking because you don’t consider it to be clean, maybe because they come from a different caste. So hold that glass, ask them for some water, and most importantly, show them the highest level of respect. We shouldn’t enter their homes with an air of superiority, that we have come from a particular organisation, or social group or more privileged background. It is only when you let go of such airs that you can really enter. It is also important to be empathetic, and not sympathetic. It shouldn’t be that somebody’s poverty becomes your aesthetic. We also don’t go to them with promises. I make it very clear that I don’t stand to gain anything from these photographs. I just tell them about the kind of exhibitions I put up, and that I don’t know where these photographs will go, who will view them, and what will come of it. So you be completely honest with them, and ensure that the sense of equality and friendship remains. Honesty in your approach and your work is what will bring change.

LILA: There is also The Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and Their Rehabilitation Act, 2013 which has now been put in place. Has that brought about any difference?

Sudharak Olwe: The problem is not the law, but the political will. First we have to work on the issue of caste. If you see the statistics of death amongst manual scavengers, it looks like that of the Kargil War. Every second day one person dies. As soon as the worker dies, the body vanishes; there is no police, no FIR. The contractor manages to give some money to the family of the deceased, and the case is not registered. You have to understand the families, the community are extremely disenfranchised, illiteracy is also an issue. They do not know what to do. This status quo is maintained as it serves the higher powers well. There is no accountability. This is happening every day.

LILA: You have also started something called the Photography Promotion Trust that works with the children of conservancy workers to teach them photography skills. Many of these students have now gone on to get jobs at media outlets and popular newspapers. Can you tell us about the early days of this project, especially with respect to implanting an idea for change. It is often more difficult to make people believe in change than actually bring it…

Sudharak Olwe: So even when I started visiting the conservancy workers regularly, they used to tell me not to come and waste my time. But I would say no, we will surely do something somewhere. So I kept visiting them for 12-13 months. They would tell me there’s nothing you can do for us; instead, do something for our children. I didn’t know what to do. I am a photographer, I only knew photography. I had just come back from the National Geographic All Roads festival, and I had met many photographers, like Shahidul Alam and Reza Deghati, who are all pioneers in social documentary. So I learnt from them and decided to do something. We chose 20 children from the conservancy workers’ community, mostly from families where the fathers had a drinking problem or other health issues, and started doing photography workshops with them. These went on for 12 years. These were all young teenagers, between the age of 12 and 16. As the workshops continued, some of these students started getting assignments and jobs at different publications like the Times of India, Hindustan Times, Indian Express, etc. After about a decade of these workshops, we partnered with the Xavier’s Institute of Communication and asked them to give us a certificate and a space, which they did. Those certificates really worked to boost the students’ job opportunities.

What is important here is that we did not start with the intent of making them photographers. We wanted to understand who they were, where they came from, and we wanted to give them a role model – that if I can do this, so can you. But for that, you need to work hard, study and dedicate time. So it wasn’t about literacy but about building trust, confidence and a bonding amongst the community. If one of them didn’t have a lens, the other would lend it, and in this way there was a bond that was formed amongst them. We did many workshops around the country as well. But the last two years we have not been doing them, because I’ve been traveling a lot. But the diploma course is established at XIC now. One of the students from the recent batches has gone for a Masters at Sophia College now. So that is still happening.

Why it was important to start this was to break that vicious cycle of inheritance of the occupation; the notion that members of this community alone were to do conservancy work. And I think we were able to do that to quite an extent. The numbers aren’t very high, but I think 20 is enough to initiate that change. Now these children are all photographers. The caste stigma isn’t there because they work at a reputed newspaper; they can walk into anybody’s house with their camera, which becomes their face. This small camera is able to give them that power.

At a later stage the Photography Promotion Trust also moved on to accommodate general photographers. They all wanted to be fashion photographers and ‘page 3’ photographers. So we would tell them that’s also good, it helps you earn money, but social photography is important. You can do it in your spare time, but you must do this. For maybe some small events or exhibitions, or even just to grow your own understanding. We started meeting photographers and started doing workshops with them. So that’s how PPT started, first with children of conservancy workers, and then now with general photographers. We also now invite photographers, artists, et al. and exhibit in public places. For the last 18 years, we’ve always exhibited on a street at Kala Ghoda on some social issue. For instance, the bridge that collapsed in Mumbai recently really troubled us and made us think about what was wrong with the city. Around 20 photographers from PPT documented the crumbling infrastructure of this city and the people most affected by it. Through this project we were asking, “Whose city, whose right?” Another project we did was on the unequal water distribution in Mumbai. Again, the 20 students worked on this project and exhibited their photographs. We don’t know where it will lead us to, but we document the issues of the city, and of the people. We also did a project called ‘Love in the City’ for Godrej. There’s not a lot of open and public space in Mumbai, so you will find couples meeting at Nariman point, Marine Drive, etc. and we photographed them. These students are all very creative, hardworking and honest with their frames. They could go close and capture these moments. We did this project with Godrej to show that there is no space in the city, no gardens, etc. We keep doing small projects like these and exhibit them. You can read about all the other social impact projects on the ppt website: photographytrust.org

LILA: You mentioned that for 12 years you have been doing these workshops with the children. At what point did they start getting projects? As I imagine that must’ve been a major motivating factor to continue learning as well, for the children…

Sudharak Olwe: After about 3-4 years of attending the workshop, they started getting wedding photography assignments and would say, “Sir, we have an assignment today, we’ll come tomorrow.” We would joke, telling the students, now they are in more demand than us. Nowadays everyone from that first batch is busy. New batches also keep coming in. Also, now the classes are open for all, and are also taught by different people. So students come from different cities like Delhi, Pune, Hyderabad, etc.

The PPT is now also working with photographers from different cities who want to work on social documentaries. For instance, one of the students from the last batch, Nilesh Gawde, a software professional from Pune had worked as an industrial photographer. As part of the workshops, I took him to shoot in Beed, Marathwada. There, sugarcane-cutting contractors were unwilling to hire women because they would menstruate, and so women had started getting hysterectomies done just to get employment. After 3-4 days of working there, I asked Nilesh what he thought. He said, “Sir, I never knew that such a problem even existed.” He continued to work on this issue, and recently even did a story for a French magazine on it. It is our attempt to open them up to such issues and show them the possibilities of the different kinds of stories that need to be told. It is very important for such stories to be told.

Similarly, when parts of the Konkan region was flooded last year, one of the photographers from our workshop, Abhijit Gujjar, documented it all from the first day to the last, and released the pictures everywhere. He realised that these were stories that could be told. He is getting featured in newspapers like The Hindu, and in the Associated Press, and is also able to build a livelihood out of this. So it is really important to open them up to such possibilities.

Another aspect of the workshops is that I never do them alone. There is always someone with me. Sometimes I give a young photographer a chance to take the workshop, while I just watch and guide from the side. In such a process, this young photographer gets trained to continue these workshops, and so on and so forth.

There is also more to this. We went to Bundelkhand to do a workshop with an organisation called Vanaggana, that works on the issue of violence on women. When we went there, and got a sense of the place, the people and their issues, we decided not to do a regular photography workshop. Instead, we organised six cameras for the six people who worked on the field, and taught them how to document evidence, things like going to the villages, checking whether the case was registered or not, and taking the required photos that can be used in court. The culmination of this project was that a local newspaper called Khabar Leheriya started using their photographs. I then asked Kodak to give them cameras so they could continue. Now, all of them are working in different spaces – some have become teachers, some have started other organisations. So photography became a way to trigger them and help them learn. That small camera became an immense source of power for them.

LILA: I had also read sometime back about a sanitation worker who at that time (around 2 years ago) was doing his PhD from TISS, and already held 5 other degrees, but chose to keep working as a sanitation worker to give back and help his community. Even through your workshops, you are talking about how photography gives a new lens to the students through which to understand the world. Have these exposures also helped the children of conservancy workers raise the cause of their parents’ working conditions? Especially since the law has not made much of a difference…

Sudharak Olwe: Yes, I know about Sunil Yadav. He took over his father’s job and tried to also get a higher post but was not successful, he worked hard on his education too. Discrimination is very much present in this society. Hence, education is very important. There is no alternative to education. But if you look at the state of conservancy workers across the country, it is difficult. You might know the Dom community, or the Mehtar community. If you go to their community, you will not find a single person who is a graduate, because their job doesn’t provide the stability to go to school. You will not be able to tell that they are people of today and extremely marginalised.

The children of conservancy workers are now aware, mindful of the work their parents do. Atul, one of the children from the first batch who is now a photographer has been vocal about his parents struggles and started conversations through his photographs of his father working in hard conditions. Following this he also earned a scholarship to study in Sophia College. For their parents, their time has now passed for change. Now it is about respect and acknowledgement and the children are able to provide that.

And now these children will never go back to doing what their parents did, that chain or cycle of oppression has been broken and I think that makes a lot of difference, more than any law can.

LILA: Today we see more awareness and more organisations working on issues of conservancy workers. Like you said, small things are happening which will also lead to some change. So now there are NGOs, trade unions, and even spaces like the Tata Trusts taking on the issues faced by conservancy workers. Can you tell us about your project with the Tata Trusts, and how projects of this nature might be able to bring different degrees of transformation?

Sudharak Olwe: As I had mentioned above, when Ratan Tata saw the pictures, they moved to start a project to give dignity and respect to the workers and also published a book of the photographs. But the work is now very slow, under Mission Garima. I cannot see effective change. I was recently watching a film in the theatres and an advertisement came on from the BMC – about the conservancy workers and how we should respect them. The video was a total sham. The worker had gloves and proper boots and jackets and tools, and they were all smiling. There is no such thing in reality. The workers use cardboard and pieces of plastic to scoop out waste. In the gullies, they are in knee-deep filth. Which boots can protect them then? It shows all public bins have garbage bags. Which ones do in reality? Also, the main issue of caste itself and the discrimination is completely ignored. The video was an attempt by the BMC to stay relevant and be seen as ‘progressive’ but is really a disservice to the workers. While we need to recognise and respect the workers – IT IS IMPORTANT – the people know WHY we need to respect them, WHY they are so disenfranchised. This ‘why’ is missing. I will reiterate – not sympathy but empathy is needed.

There are many agencies now working in the field of sanitation in India. Even international ones. But they are so far from the ground realities. Policy making can be done only when you are with the people. Listening to them, understanding the caste dynamics of the community and region. Many of these people sit in their offices, working on funding and grants and try to make sense of the issue without even understanding the people they are ‘trying’ to work for. There is a misplaced importance and also ignorance. Most of the agencies and their waste management solutions are market driven and not human centric.

I recently did an exhibition for which I travelled to three states. In one of the villages I travelled to in Bihar, an organisation that I will not name asked conservancy workers to leave their jobs. It was frustrating to see that the entire community now has nothing to do. Children were playing, men had no jobs. So when the conservancy workers told the villagers they will not be cleaning their gutters and toilets anymore, the villagers decided to boycott them completely. They didn’t give them any work at all. The shopkeepers stopped giving them loans. So the husbands started going to the cities and cleaning the drains there. Some even died while doing this. The families of the deceased were still waiting for rehabilitation packages, which would give them Rs. 40,000. So they will go through the bureaucratic processes, after which some may get the money and others may not. But their status will still remain the same. Rehabilitation package has to be so good that they should not have to go back to the same work. So, unless we don’t establish their equality and assert their rights in society, there won’t be any lasting impact. Even today, the upper caste community in this village tells their children to stay away from the valmikis (low caste/Dalit) and not touch them or interact with them because they come from a lower caste. No matter what programmes we set up, this practice is still getting passed on to future generations. In many villages I saw that even though toilets were installed in the name of Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, they still don’t have water or drainage systems to support them. So, all these toilets are used as storage areas instead. Similarly, the government passed an Act saying manual scavenging is illegal now, but we are still seeing it everywhere around us. At least there should be some record of what is happening in front of our eyes. Because we don’t acknowledge that, we don’t even see the repercussions of these systems on our resources, like the pollution the current sewage systems create in the water bodies. This is also an engineering problem. In all the years since our independence, we have reached the moon and Mars, but we haven’t been able to fix our sanitation systems. Our cities are dirty and our villages are dirty. What are we doing?

LILA: From your experience, would you reflect on the medium of photography, and the power of the image to make change? What kind of image can bring such transformation?

Sudharak Olwe: I call my photos of the workers as not a pretty picture. They are not and they should not be. It is important that all persons living in a society accept and see the realities of life from all corners and many times these realities are not pretty or beautiful. They are hard hitting, gut wrenching, and they question the viewer and leave you with many questions yourself. This is the kind of images that are needed to make change. Questions bring out reactions, reactions start dialogue, dialogue leads to action.

LILA: If it is the direct depiction of poverty or injustice that attracts maximum public attention, would you consider it a danger if images tend to develop a sort of exotic life of their own, outside of the lived realities of individuals?

Sudharak Olwe: It is important, then, to look at the context of the images. Where they were taken and why. Who is looking at them and why. The purpose of documentary photography is that such photos do not have to be taken again. That the hard situation shown in the pictures is rectified, corrected so that the image is not made again.

LILA: Do you think at some point, there is a need for the Dalits to let go of their identity in order to be truly equal with everyone else in the society? Is the Dalit struggle itself a trap that does not allow one to transcend the caste barriers?

Sudharak Olwe: In a country where people will judge you and segregate you according to the language you speak, the food you eat, the name you have and the color of your skin – How is leaving your identity a solution? The society needs to leave its archaic belief system. The caste system has to be abolished. Equality for all people, all genders and religions has be established. Then there will be no identity to let go off; one can be free to choose who and how they identify themselves with. The trap has been designed by the upper castes. As Ambedkar rightly said, the caste system is not merely a division of labour. It is also a division of labourers. It is a hierarchy in which the divisions of labourers are graded one above the other. The struggle of the Dalit is a struggle for equality.

LILA: Because the Dalits themselves belong to different classes today, say, your class and education is very different from a Dom’s. Do you have some thoughts on the question of policies concerning reservation etc. given the above disparities?

Sudharak Olwe: My crossing the threshold is not a result of a fair system – it is because of factors like accessibility, me living in a city, the right time, and also luck and the CHOICE of my profession. The camera in my hand allowed me to cross obstacles. The camera is a powerful tool and even the most powerful people are afraid of it. It was what I used for my fight and journey. Most of the Dalits and lower castes do not have the luxury or accessibility I enjoyed. I have always been mindful of my privileges. Then as well as now. Equal opportunity in a society is possible when all people are treated equally, but that is not so. In our country, the social fabric is extremely complex and layered. Reservations are to correct the disparity and injustice of the past 2000 years. We have been independent for only 72 years–a very less time for the upliftment of the millions who have been denied education, water, dignity and justice.

LILA: What is your aspiration/dream for the Dalit movement, and how feasible is it to find its fulfilment given the reality around us?

Sudharak Olwe: My dream? The abolishment of the caste system and the complete rejection of patriarchy. The day when sewage workers stop dying in our gutters, that will be the first step towards that dream. The day when untouchability and casteism become a thing of the past, we will move closer. How feasible is it? That we cannot be sure, but what we need to do? Educate, organise and agitate.