LILA: Let us begin by situating the question of language and people in the context of India. While the last Census (2011) recognised a total of 121 languages in the country, the People’s Linguistic Survey of India, which was initiated in 2010, estimates the same to be around 780 on the basis of a “people’s perception of language.” Please tell us more about this – what is meant by a people’s perception of language, and how is it qualified and utilised in a study as vast as the PLSI?

GN Devy: There are three things that we take into account.

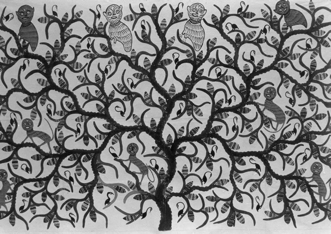

The first is the biological natural evolution. The homo sapiens came to be a distinct species because of the peculiar structure of the human brain, which is described as the recursive brain, that is, it can think about thought. Because of this unique capacity, it became possible for human beings to speak out and articulate their thoughts. This is the origin of speech, which creates an image of reality apart from reality itself. For instance, there is a tree. When I use the term “tree”, the object tree is already there but the word tree comes into existence. Now this new coinage starts circulating and connecting one member of the species to another member of the species. The homo sapiens became ‘people’ and not just ‘a group of animals’ because of language. When ‘animal-members’ become ‘people’, they start developing collective memory, which is a surplus, over and above the sum total of memory of every individual member of the species. It is neither yours nor mine, but something over and above what is yours plus mine. That surplus of memory is the foundation of our ‘being people’. It keeps us bound together through shared ideas, shared meaning of words we utter, shared implicit concepts and therefore a shared worldview. So a given people have a preference for the language they use, but it must be remembered that it is the language that makes them a people. So the people’s attitude to their language is invisibly guided by the language that people use.

The second is located in our contemporary situation. The Census of India has been counting ‘mother tongues’. Please remember that what the Census describes as ‘mother tongue’ is not always and necessarily a ‘language’. In the last count in 2011, the census accepted 1369 mother tongues, and further grouped the mother tongue in categories called ‘languages’ which were 121. So speakers claim that there are 1369 mother tongues and the state claims that there are 121 languages. These two attitudes govern the behaviour of language in our country. Government is interested in foregrounding a significant diversity but not all of it. Yet the people have been going out in every census to say that our mother tongues are a lot more in number than what the government will accept. This shows the people’s attitude to languages.

Thirdly, language is a very fundamental tool in maintaining one’s livelihood practice and whenever there is not enough livelihood available in a given language people cross the linguistic borders and enter the borders or zone of some other language. For instance, you speak English for your work, which may not be your mother tongue, but has to be spoken for work purpose. This does not mean that people like to forget their own languages. This only means that language is a pragmatic choice that people make in order to remain alive, in order to survive.

LILA: This seeming dichotomy between the actual utility of a language versus the established identity of a language is what I would like to explore with you. The reason for a difference in numbers from the Census of India and the People’s Linguistic Survey of India is largely bureaucratic. But in the midst of such exercises and questions of livelihood, what happens to languages and their true identities? Do you think people’s sense of identities dependant on language also gets affected in this process?

GND: See, people think that government policies will do something for the languages. But if you see the way languages behave and the way people handle languages, it should become obvious to any good observer that governments have very little to do with language growth or language decline, because government do not make them, people do. Language is till now the most democratic among the social systems that humans have invented. Languages allow access to just about anybody despite their age, social status and education. No fee is levied for speaking a given language. In the history of human languages, the role that the governments have played in regulating them is very minimal. Humans have been using languages for approximately the last 70,000 years whereas language policy as an entity is barely 150 years old. Prior to that, languages were born, they developed, they declined, they perished – all of that has been happening in the human history; and whether there are governments in the world or not, humans will still use languages.

Another assumption is that if languages are taught in school, they might remain in life for much longer. There have been mighty languages in the past that have been taught in schools, for example Latin or Sanskrit, which have perished. On the other hand, the languages surrounding Latin and Sanskrit which were not taught in schools and were called vernaculars or barbaric and prakrit and apabhramsh languages, respectively, by the Latin and Sanskrit speakers grew into modern European languages like Italian, Spanish, French and Portuguese and the modern Indian languages like Bengali, Gujrati, Marathi, Hindi, Punjabi and so on.

The closest one can get to this is by using the example of the ozone layer in the atmosphere. The governments do have a lot to do with the ozone layer but the governments anywhere in the world are far too insignificant to do anything with or about language. That, if languages are taught in schools, they will remain in life for much longer, is an assumption. So what you mention is indeed a dichotomy; but it is not foundational to the being of languages. If I were genuinely interested in understanding what is happening to languages then I would not spend too much time debating the role of governments, though I shall not ignore it entirely.

LILA: Why I am interested in discussing this aspect is also because today we see that the natural progression is not so natural anymore. There is a kind of a violent intervention that is being made…

GND: Yes, that is so.

The very first thing that we need to note is that language is not an organic system such as plants-system or animal-system, but a social system like the church-system or the caste system. A social system is something that the humans have created even if not entirely rationally. We normally know its origin and we know its ultimate aim. These are systems on which human societies have reasonably full control, unlike the organic systems. So when one speaks of the life of a language, life is used as a metaphor. But to think of its growth and its decline, it is far more profitable to think of language not as a life-system but merely as a social system and then ask questions like why these systems are collapsing. What are the fundamental reasons for the collapse? I think that way one gets a better view of why a given language replaces another language or why one language suddenly develops the energy leading to its growth.

LILA: That is a very valid point. And none of these systems exist in isolation, so how they interact with each other would also influence their trajectories. While conducting research for the People’s Linguistic Survey of India, did you observe such interactions? Are there any subsequent insights you can share with us about such dynamics?

GND: The reason for carrying out this survey was that in the 1961 census, a list of 1652 mother tongues had been released. In the 1971 census, I saw that the list had come down to 109 only. So I was very curious as to where these other 1543 languages had gone. This was when I was a bit young, in my late 20s. So I decided for myself to take up the mission of identifying where the people who spoke these languages were, and how they were living. I noticed that most of them lived in tribal areas. Now this led me to a new question – why is it that in India there is the Dravidian family of languages in the south and Indo-Aryan family of languages in the north? Of course there are other families of languages also; but why is it that the two did not merge to make a single language family, though they have coexisted side by side for several thousand years? Once again, that actually brought me to the observation that it is in the middle part of India that we have a dominance of tribal communities that speak different languages. As I started my exploration of their language, I realised that there were many other things about the Adivasis that one needed to know – such as their worldview and the level of wisdom that they held within themselves.

These were realisations for me. Previously, I had studied in a good State University when I was in India. Then I went to England and studied there; and I had returned home as a modernised rational man, completely steeped in Modernist literature. My contact with the tribal communities made me think again on practically everything and also taught me great humility. I realised that I knew practically nothing about these people and therefore nothing properly about Indian history, society, cultural systems and cosmos. Through several decades of thinking about these questions and working with these communities and their languages, I noticed that their languages were disappearing very fast, faster than they needed to. I also noticed that other languages, which are non-tribal, were also on a fast track of self-destruction. Then I started looking around at other countries to see the situation there and it dawned upon me that there is a crisis among languages all over the world. I realised this somewhere around the ‘90s. This was also the time when UNESCO started sending the alarm about the declining languages. I was not associated with UNESCO at that time. My realisation came from my contact with tribal communities. When I started thinking about the epidemic scale of language decline in the world, I realised that there is a deep structural change in the human brain that has started occurring in a greater speed than before. The part of the brain that analyses language and makes sense of our existence, which is called the Broca’s lobe, has developed a great fatigue. The human brain is now in a mood to refuse to use sound based communication, i.e., language, and is rapidly moving towards visual communication, which is image based. In other words the world was on the verge of becoming silent. Humans are in the grips of a strange kind of aphasia. This was the realisation: after 70,000 years of using sound based social system of meanings, humans seem to have given up on that and are deserting it very fast. Increasingly fewer and fewer languages, and in those languages far fewer words, will be used. Individuals will learn to manage their lives with fewer words. Even today we are doing that. If we were to do a documentary on a typical individual from morning till night and note down the number of words she/he uses in comparison to what was in practice 50 or 100 years back, then it will be found that language stock in use is extremely limited today. More people are speaking English Language all over the world but collectively they are speaking much less English than was spoken in any other phase of the English language in the past. The same is with any other language. There is no growing language in the world. All languages today are diminishing languages, whether they are small or big languages.

LILA: Do you think this kind of development has a connection with increasing intolerance and problems of diversity?

GND: What you think is the cause is the consequence. It is not because of the intolerance and rise of dictatorship that languages are declining. It is because languages are declining that humans have entered a phase of intolerant state and non-Democratic societies and are entering an era of increasing contempt.

LILA: In this context it is interesting to look at the work that the Adivasi Academy and also the Bhasha Institute have been doing because it’s not just a collection of information that you have published or an archive that you put in files and then you keep it. There is some kind of translation of it that you want to see in the public space. Can you tell us about how you view this because otherwise all these projects are like archival projects. They think that it is important to record and then store them somewhere. But how do you use this to then respond to the context that we are in today? Especially because the last few books are now coming out in 2020…

GND: Trained professionals dealing with psychology, linguistics and neurology consider it their duty to contribute to that field of knowledge. The Bhasha Centre was not explicitly created for adding the knowledge stock of either Psychology or Sociology. It was created explicitly with the idea of enhancing the quality of life particularly of the marginalised communities. Therefore, we were not interested in documenting in order to attain very high standards of archiving. Of course, that has its own use. We were interested in reinventing our knowledge or experience about the life of the communities. We were interested in mobilising them around the question of language and identity and giving them a sense of pride about who they are, bringing them to think on equal terms with the rest in the world. So our aim was to build a collective confidence in social ownership of the language institutions and culture. All that we did was for the sake of the people. Besides, I always very firmly believed that this work needs to be done by the people themselves and not by some outside consultants or external scholars. Of course I have no allergy towards such experts or consultants since they too are knowledgeable persons; but I was trying to develop a different method of knowledge creation. If people could generate knowledge about themselves, it would be more authentic and it could circulate in the community more easily since University books will not always circulate among very poor communities. This knowledge circulates in the community and thereby increases the community’s desire to own its cultural practices. It makes the community think about the desirability of their cultural practices. This is a sustainable way of going about it. Once you tell people to mobilise their culture and language, they invest more in their cultural-language as well . Over a period, the given community should adopt a degree of desirable modernity and not blind imitation of the modern of the west. This is what we did. Very consciously we chose our path differently.

The linguistic survey was done without any government help. I was very proud that it was being done by the people and for themselves. Now there is a tangible body of knowledge produced by these communities, and we have published volumes for all states except Andaman and Nicobar Islands and we will be bringing it out in the next month or so. This is a massive document which will help people in the future to understand the linguistic heritage of India and all of it is generated by ordinary people. It is only some of the colleagues in this experiment who were experts but a majority of them belonged to a class that one can describe as not starkly illiterate but reasonably uneducated. This vast body of knowledge was produced by this reasonably uneducated group of individuals.

LILA: I also want to understand the methodology of developing this because now you have moved to Dharward where you are helping fight the case for M.M. Kalburgi. The violence that we saw used against him was also used against other such rationalists and their institutions. When communities try to reclaim their position in society or create a strong identity that cannot be oppressed, there is often a violent opposition or reaction to that. I’m interested in knowing your methodology in this context also, because your work is moving towards that direction, though violence is not so predominant where someone is trying to preserve languages or continue the historical process of cultures and their development.

GND: I have firm views about dissent as a social norms, the need for law and order, about what justice is and should be. When I see that there is a need for my intervention anywhere, I do intervene to the extent that it is possible for me. So my taking interest in the cases like the murder of M.M. Kalburgi, Gauri Lankesh and others arises from my sense of justice. This is something that comes naturally to me. It was not a conscious decision or a career plan and I will continue to do so till I have energy and I am alive. That is one part of my life. In the past, I have fought for tribal rights, rights of nomadic communities and so on. That is one part of my being and I ascribe that to the influence of my predecessors like Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Mahatma Gandhi Arvind Ghosh, Jawaharlal Nehru and Tukaram and so on.

There is also another thing which is that I have been trying to develop a method of knowledge generation because I feel very deeply disturbed by the present situation in the field of education. I have studied in India and England. I have spent time doing literary research in the United states; which is why I feel that what humans consider knowledge itself is a problem area for me. I have written on this question, in a book called Crisis Within Knowledge. The essence of what I wrote was that all of us believe that knowledge will bring us greater freedom. I believe that knowledge will not bring freedom to you but freedom will bring knowledge. That means setting political systems in order, resetting the social relationships, revisioning what we do with the institutions of profit and institutions of labour and labour practices, particularly in the case of women. We also need to reset our ideas of happiness. What constitutes happiness and what the ultimate aim of human life is, and therefore what the meaning of human existence is. I tend to think that it is necessary to grapple with all these are questions. Nobody has asked me to do that. None of the positions I held or the work I did in my professional life I requires this kind of questioning and thinking; but from very early in my life I have been struggling with these questions. I do not claim that I have found the final answers, but I feel it was necessary for me to revision what knowledge is and therefore to establish a new method of knowledge generation. I firmly believe, what comes out of experience qualifies to become knowledge, and so also what comes out of labour qualifies to be knowledge. I’m not adhering to any theory of Karl Marx, Gandhi or Ambedkar. They were surely all great persons; but I don’t think I am sufficiently influenced by anybody to become a poor copy of anybody.

LILA: I want to come back to something that you had written recently in the Telegraph, where you wrote that the reason for the protests we saw over the last three months was not for one or two causes, but a result of revisiting what it means to be a people in this country. At this moment when we have arrived at this realisation and have also been hearing your thoughts on people-driven movements, could you also share your insights on the way for a people’s governance to be brought into operation…

GND: Yes. These are three levels of being here.

The first is to be a people, that is, to be linguistically composed as a community.

The second involves the nation, that is, to be linguistically composed and then territorially affiliated.

The third is to be citizen, that is, to be linguistically composed, territorially affiliated and then be governed by a set of rules and regulations which have provision for punishing and no provision for rewarding (By nation I mean a group of people and not a piece of land).

Now to give an everyday example, if you have a lot of disturbed sleep, you wake up and remember what was going on in your mind when you were asleep. This memory is not a clear memory, it is like a memory of a dream. A given society sometimes becomes confused, creates a lot of noise and become somnambulist. I am not talking about physical rest but the sleepwalking tendencies that take over the society.

Sometimes, they remember a deeper layer of their being a people, and out of that they draw a solace and direction to reorganise themselves. If I had written a longer piece in the Telegraph, I would have added more. So, imagine that from this point on we will emerge as a more responsible democratic society. It is true that resting has become difficult because there are fears surrounding us and intimidations surround us. Previously unheard of things have been happening. It is also true that the constitution we thought was a very steady deck on which all of us were on a long democratic voyage is not so steady anymore, as it is being tinkered with. But this in my opinion is a passing phase and India, being what it has been, will go forward in the era to come as a very strong egalitarian, democratic nation. There are two great things about India. One is its ability to live comfortably in uncertainty about its many origins – where one begins the story is difficult to say. Everybody can begin their stories at different points and all of us know that all those stories are equally true or not. All of us are comfortable in not knowing the exact origin of India. That is a great blessing. The second great quality is that Indians have valued and maintained a continuity. So Indians are able to live comfortably in the middle of not knowing exactly where the country is going, but at the same time knowing that wherever it goes, it will maintain a continuity. This continuity is with the tradition that emerged over the last thousand years through writings of humanitarian thinkers, religious reformers, Freedom fighters and so on. We will maintain continuity despite temporary diversion.

LILA: You said it is not through knowledge freedom will be attained but through freedom that knowledge will come. I’m trying to understand this in a very practical way when you work with communities that have lost livelihood opportunities that can support their identities and their cultures and like you said now they have to adopt these things for practical purposes. In this place how important do you say is the role of livelihood in attaining that freedom? Is it a limiting question in terms of practicality because we know that unemployment is a serious problem today.

GND: Let us try to answer this in a relaxed manner. Around 1600 AD the East India company was set up. It was spread all over the world and by 1900, that is, roughly 300 years that it took for it to become a mighty empire. In 1900, nobody ever thought that the sun would ever set on the Empire. Now during those 300 years, particularly during the 19th century, many philosophers and social reformers on our side also thought that we must become like the colonisers and that it was the only way forward. Some 50 years later in the 1950s, 3/4th of the empire had gone. In another 70-80 years the company that had formed the empire itself was in a terrible shape. This is the story of about 450 years. You take it forward to another 70-80 years and make it a good 500 years story, and there is a lesson for us to learn from that. It is not that history will always repeat itself. The lesson to learn is that what may look threatened at one time and the one who may look intimidated at one time, may yet again resurrect itself. I will tell you why I am saying this. If we look at the ideas of development anywhere in the world, not just in India, but you take Canada, Russia, Argentina, whichever country you want, those ideas of development appear to lead to blind alleys. The visions say that there shall be either complete ecological disaster forcing humans to become aliens and asking them to migrate to some other planets or humans will have access to limitless energy and a life comparable to that of the divine beings (if they exist). But neither of these take humans forward as humans. On the other hand, indigenous knowledge is capable of helping humans to go ahead while retaining a reasonable balance between the ecological and the economical. That being so, as time passes, most of us will turn towards that wisdom. I’m not saying that all the wisdom in the indigenous world is ready made for our future use. It is not like a cupboard or locker that you can open, take the treasure and put to use. We will have to first come to terms with the indigenous people. There are, at the moment, all over the world roughly 37 or 38 crore tribal (indigenous people). That is about 4% of the world population. But possibly the secret for survival lies in the lifestyle of these 4% people. These indigenous people are not my monopoly of course, and I’m only making some observations based on my experience of the larger world, in India and outside India, on the one hand, and the indigenous and the nomadic communities, on the other hand, since I have observed them both at very close quarters. I am not speaking in terms of “those people” or “us and them” that is not the idea. I am only an observer. But as a vigilant observer, I can say that their small numbers do not matter. A day will come when the remaining 96% people will have to turn to them.

LILA: The latest COVID-19 pandemic has raised alarms about our lifestyles and forced us to rethink our course as a species. Do you think that day, when we must turn to the insights of the tribal communities, has arrived? Where do you see this transformation happen beginning – which parts of the world, and how?

GND: It is difficult to predict where the pandemic will lead us. Our first priority is the survival of the human species. The next priority is to reshape the human society so that continuous survival becomes possible. Time will tell if humans acquit themselves creditably during this moment of crisis. Let us hope, they do.