Civilisation, the culture of making settlements and cities (the Urban), began almost 10,000 years ago. In the beginning there was ‘space’ – vast and ample ‘space’. Space where flora bloomed and fauna roamed in gay abandon. Everything was ‘outdoors’, or perhaps there was neither ‘outdoors’ nor ‘indoors’, as there weren’t any ‘doors’ in the first place. Till one day the human-being decided to build its own built-form in the name of safety, security and shelter. The human being, the maker, creator and perpetrator of all things that didn’t occur naturally, carved out tiny spaces, enclosed and covered from the existing vast and ample space interfacing the terra firma with the rest of the universe. Architecture happened.

Are the built and the un-built, the tangible and the intangible, the tactile and the non-tactile, in conflict perpetually, or are they in tandem eternally? Is it a duality that is played out or a synchronous co-existence? Architecture and Urban Design have battled and lived with these thoughts ever since we attempted to read, analyse and infer the physical form of the human dwelling and the human settlement. The ‘built-form’ and the ‘unbuilt-form’ are like the yin-and-yang of the habitable space as they shape and define each other in abstract unison. The Architect or the Urban Designer consciously builds and non-builds, to suit and support human functions through these forms, by interlacing activity and behaviour between the space and the person.

The human being, neither a lonely predator nor a member of an unquantifiable herd, is a pack animal who loves to live in recognisable groups of recognisable characteristics and bonds of faith and fraternity, love and loyalty. From a sizeable group of a clan, to smaller packs of large families, to nuclear units, and finally to the individual, the human being has disintegrated its togetherness into the mess that modern urban life is much about. Yet the natural, primordial needs of a ‘community’ could not fully disappear.

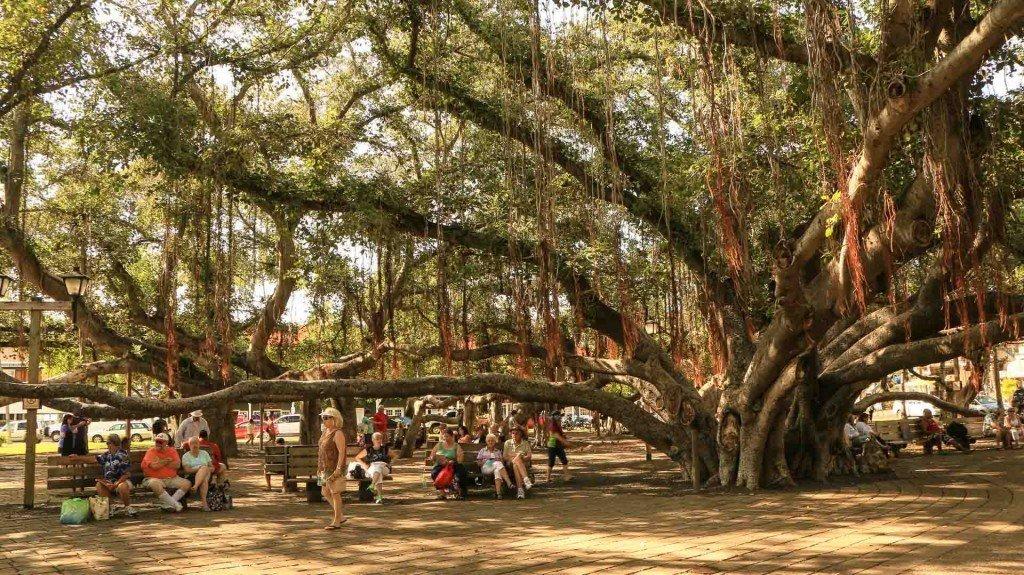

The space where the community comes together, to interact, celebrate, contemplate, perform, protest or simply hang-out, is generally the public precinct, which forms the better part of Public Spaces/Places in any city or town at all times in the history of human settlements.

Public Spaces may have a sense of enclosure, therefore, girdled by built form; having a non-wearable surface, therefore, paved; having a predominance of civic activities and sparingly green. These Urban Spaces are often in the Urban Designers’ domain.

Public Spaces may also be un-enclosed, by merely having a fence/compound-wall; having a soft and green surface, with some paved paths; having leisurely activities and predominantly green. These Urban Open Spaces are often in the Landscape Designers’ domain.

So, Public Spaces are traditionally open spaces within an urban environment, spaces that are meant to be outdoors, accessible and social. They can be hierarchically classified in accordance with their proximities and usage to individuals and communities; and range from a compact cluster court to a sprawling town plaza, from a narrow bazaar street to a royal market square, from a tiny tot-lot to a vast esplanade or maidan. It is a bit difficult to precisely define their characteristics and yet they are vaguely and intuitively recognised by most. One could do away with definitions, which, in their quest to be absolute or perfect and precise, often complicate things to such an extent that they vilify the meaning and stop making sense altogether.

The space where the community meets and interacts is just a community space; once expanded it becomes the Public Space in a settlement. This space need not be linear, and it does not need to have a “here to there” orientation. A community or Public Space should be multi-directional, multi-use and multi-dimensional; quite in contrast to the uni-directional street. Yet, streets are one of the undisputed ‘public precincts’ that have retained their plurality in the wider sense of the term.

Yes, streets are an intrinsic part of a human settlement, more intrinsic than any other element or component. Street life, street food, street bazaars, street art, street performances, street sports, all have evolved from this simple straight forward open space that no city can do without. Streets are positioned in arguments on urban social behaviour, urban aesthetics, urban health and even urban crime. Streets have been subjected to expressions of power, efficiency and development.

Perhaps in the past, sometime somewhere, the Street and the community or Public Space simply overlapped or juxtaposed. Two spaces and two activities quietly came together to co-exist and provide efficiency to space. As the street could never become a private precinct by the very nature of its purpose, it was an ideal place for the unintended and uninterrupted overlap. Two open community spaces, by virtue of a singular common property of being “public”, and nothing else otherwise, came to be identified as being one and the same. It was a mere marriage of convenience. But, where, why and how did the Street as a veritable Public Space emerge and settle down into the human settlement is a mystery.

Streets, those are crooked, with their twists and abrupt turns, narrowing down at times to a point of exasperation and opening out at other times to widths that refute the street to a square or a chowk. Streets, that are clinically straight and orthogonal, orderly turning at right angles (or some other specifically standard angles) and consistent to a width to be changed only if needed, but after a junction or a crossing then right up to the next. The ‘winding’ and the ‘streamlined’, the ‘organic’ and the ‘disciplined’, the ‘spontaneous’ and the ‘planned’; the argumentative street lives on.

From a no-street Catal Hu-yuk to the orthogonal Mohan-jo-Daro to the crooked streets of medieval towns to the puritan straight lines of modern settlements, the journey has been long and intriguing. And as long as the congestion of ‘flows’ in the street remained tolerable, the dual existence sustained its singular identity. However, as the pathway gradually got overloaded, crowded with various types of flows, higher densities and increased velocities; the strain between the two overlapping spaces begun to show. The street gradually developed the inability to accommodate the community space and vice-versa. The transformation was gradual and of varied kinds, but its evidences were there all over. The street was bi-furcated and tri-furcated further as footpaths, cycle tracks and bus lanes were detached from the vehicular carriage-ways. Curbs, verges and medians sprouted as separators and some sported railings as well. The horizontal divisions were staunchly in place and growing by the day.

Comparisons, equations and arguments on the ‘old streets’ and the ‘new streets’ echo every corridor of any school of architecture and so does the laments on the rapid demise of the street life, street culture and the good times of yester years.The idea of a street as “an extension of the house”, a space where the community meets, interacts and spends a good part of its public life seems to be a thing of the past and a popular past-time of the ever complaining modern urbanists.

Public Spaces began to be a burden on the urban planners as they now demanded their own defined space/s other than the Streets and obviously eating into otherwise buildable square-area. Do such spaces gradually become a burden, too heavy to carry a financial repercussion, for the real estate developer and planner, or have they quietly and succinctly morphed or metamorphosed, in keeping with the times and its way-of-life, into a formless virtual world of e-platforms and apps.?

Going back, perhaps the street was never really an extension of the house. The roof-top living, in old cities, truly bears that out. This reminds me of some existing old towns and cities, like Banaras, where hopefully till this day the young and the energetic continue to hop-skip-n-jump across rooftops in pursuit of a loose kite and manage to cover furlongs in the same vain. A spick-n-span roof-top precinct as the Public Space shared by all neighbours of the neighbourhood (mohulla); was vertically detached from a generally messy and smelly street (gully) cluttered with various overflowing titbits from wastewater to orphaned-animals to homeless-vagabonds.

We need to understand settlement planning and design as an effort and endeavour in achieving a habitable environment that is live-able and love-able, rather than simply and cheaply use-able and consume-able. Architecture and Urban Design cannot merely be a game of numbers and numerical value systems. The overarching dependency on statistical numbers and numerical values emerge from our obsession for the measurable. Floor Area Ratio (FAR), Percentage Ground Coverage, Dwelling Units per Hectare, Tender Costs and Lowest Tender (L-1), Proportionate Distribution of Land use, Minimum Right-of-Way (RoW) etc, and the continuous efforts to Quantitatively Standardise everything in the name of Quality Control result in Tables, Diagrams and Spread-sheets taking over Planning and Design processes. The din of the “Square or Cubic Meter” and the “Per Square or Cubic Meter” drown out all Subjective, Qualitative and Sensory aspects of human habitation.

The act of the Planner or Designer ought to be recognised as being beyond the mere numerical logic of juggling numbers of various kinds that are add-able, subtract-able, multiply-able and divide-able; numbers that are statistics-able, account-and-audit-able and Microsoft Excel-able. Our single-minded focus on the given quantitative brief has regularly made us ignore the impact assessment of our acts of planning and design on the being of the human habitat. If we pause a while in our mad rush to succeed and achieve our personal professional dreams and look at the urban forms that we leave behind as footprints in the evolution of human habitat, we will witness the gradual demise of the very reason of our existence and purpose.

With a heart laden with sorrow,

I indignantly shuffle to my burrow.

To quietly introspect,

Each space a suspect.

Heck! Is extent of design so narrow?