Photo: By Chatnam House (Britain, Gandhi and Nehru) [CC BY 2.0 (via Wikimedia Commons)

LILA: Thank you for agreeing to be a part of this quarter of Inter-Actions on ‘Language’. As the release of this issue times with Gandhi’s birth anniversary, we would like to engage you in a conversation about MK Gandhi’s language and style. Economy of language was one of the most remarkable features of Gandhi’s communication. He had a characteristic style that helped him successfully connect with the life and aspirations of common people, helping them understand and participate in the processes of governance. How do you understand Gandhi’s use of language today? How would you comment on the style that he employed to articulate organic ideas and connect with ‘others’?

Gopalkrishna Gandhi: I can offer some thoughts on the style of speaking that Gandhi employed. Towards this, I give below some edited excerpts from the Alladi Memorial Lecture in Hyderabad (October 2017). The lack of what may be called word-power, word-voltage or word-art makes Gandhi’s literary style frugal rather than prodigal, sparing rather than demonstrative, prudent rather than indulgent. Nourishing rather than lavish, it seeks to convey rather than impress. Under-statement with Gandhi is not a device, it is his bani. Non-exaggeration in words is a branch of the tree of his non-violence.

Here I must say something I always find hard to say because it invariably causes disappointment and almost a hurt sense of disbelief. ‘Enough for everyone’s need, not for anyone’s greed’, are not Gandhi’s words. ‘An eye for an eye will end up making the whole world blind’ – again, are not Gandhi’s words. That witty line ‘Western civilisation is a good idea’ – I am sorry to have to say – was never uttered by Gandhi. The so-called Seven Sins were not written by Gandhi, only cited by him. And the now most frequently quoted and celebrated “Gandhi quote” – ‘Be the change you want to see’, is not a Gandhi quote.

Anyone familiar with his bani would know that Gandhi could be brief as in an honest-to-goodness telegram but not as in a clever-clever commercial ad. These examples of ‘not-Gandhi Gandhi quotes’ are embroidered versions of his thinking. They are not un-true to his spirit, but they are not Gandhi’s words. We will not find Gandhi in one-liners. We will not find him at the end of short-cuts. We will find his thoughts in his own quite simply exceptional or exceptionally simple words.

Gandhi’s literary bani has the strengths of his personality. It is frugal, it is focussed – qualities that are valuable in themselves. In its keenness to gain the maximum effect in a given space, it also shows legal conditioning. In its desire to convey quickly and persuade swiftly, it shows political urgency. In its desire to describe the issue, define the ‘problem’ and state his conclusion, it shows a prescriptiveness. This can lead, at times, to a certain abruptness. Young K R Narayanan asks him what one is to do through non-violence when the choice is not between two wrong paths but two right paths. A good question by any standards. The answer is brusque. But, to Narayanan’s equally sharp question on how a Harijan who goes abroad can serve his country and his community, the reply is brilliant, if also diplomatic: “When abroad, you will say it is a domestic question which you are determined to solve yourselves”.

Gandhi also uses, to achieve his purpose, a technique that startles. This may be called a technique of messaging, a precursor to the modern tweet. This is his genius for coining names for journals, institutions, movements, agitations. They are all brilliant passwords. Take, for instance, his description of the Great Salt March as an occasion for Right to put Might in its place. Right against Might as a three-worded gentle inversion of the classical ‘Might is Right’ has the rhyme retained, with the message turned on its head.

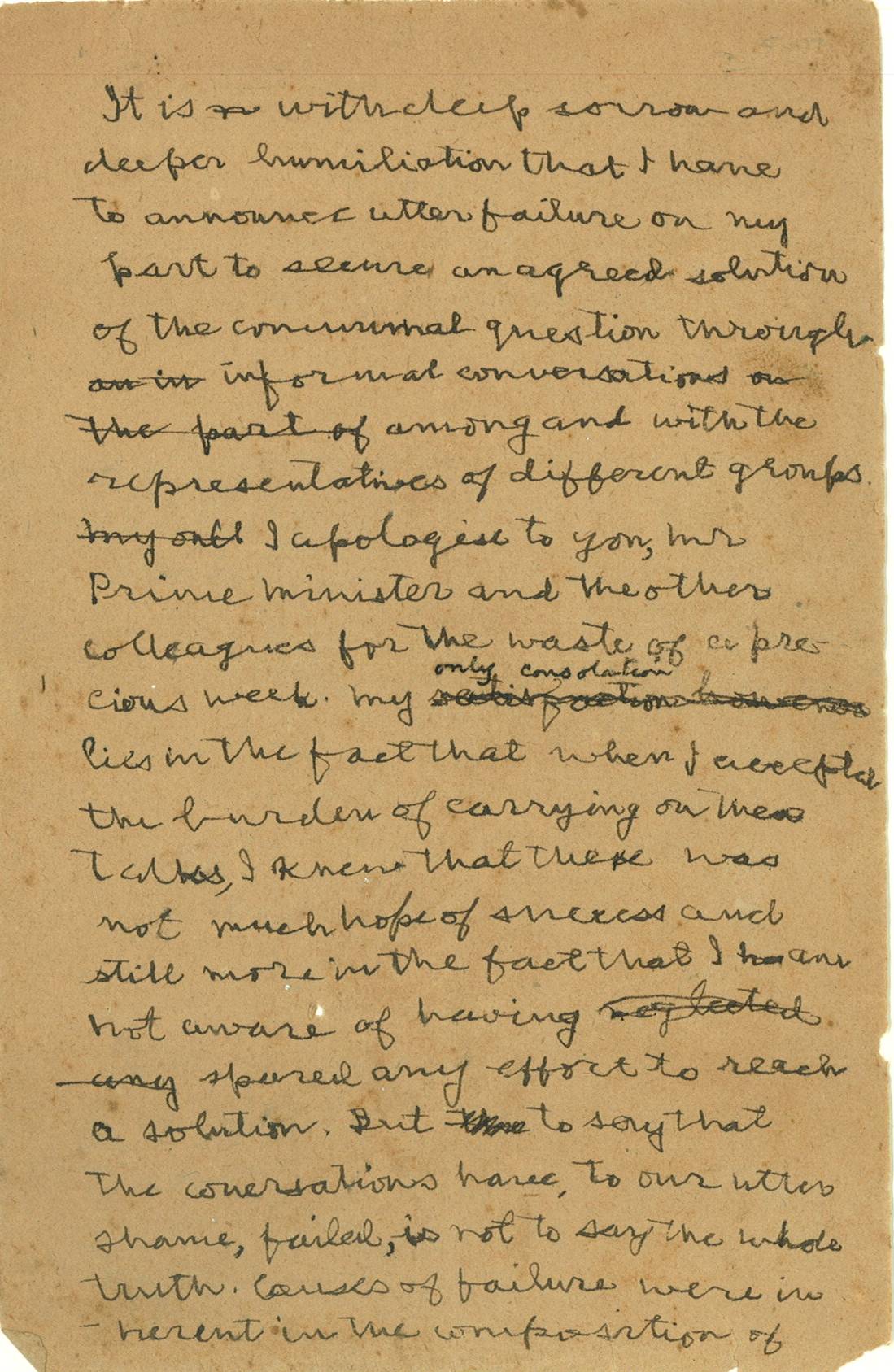

Writing for an article or drafting a speech saw Gandhi’s drafting abilities reach the acme of his style. His speeches at the Round Table Conference in London in 1931 show him at his best. The one towards the end, when he announced the talks’ failure is a masterpiece of his bani. It has courtesy, it has strength. It has modesty, it has self-respect. It should be read by all who value integrity of expression, of form and content. It was written in the wee hours of the morning after no more than a couple of hours of sleep. The revisions in it were minimal.

LILA: As an academician, a diplomat and Gandhi scholar, do you think we can develop an idiom of balance, irrespective of linguistic differences, to objectively discuss the adaptability of Gandhi’s ideas for our times? Can the particularities of different languages help in this regard? What are your comments on this, considering the multilingual Indian context?

GG: I am not sure if ‘we’ can or even should ‘develop’ any suggested idiom or style for this purpose. That would be paying a compliment to style-prescription, a form of uniformisation. A speaker’s or writer’s style has to come from her or his (to adapt a Blake image) ‘furnace of the brain’. But, yes, adopting something one admires is always an option and learning from Gandhi’s prudent choice and use of language would be to the good. I would urge reflection on ‘choice of language’. An adept though he was of English, he consciously strove to speak and write in what he recognised as Hindustani in which he was no stylist, not even particularly proficient. But he was effective in its use, in its deploying. And he could, even in his bare-bones economy of words, be something of a stylist. Take one of his better known lines in Hindustani, addressed to his political heir, Jawaharlal Nehru. Gandhi found, towards the very end of his life, when he was himself recovering from the ordeal of a fast that, unbeknownst to him and to most others, Jawaharlal had also undertaken simultaneously. One could call it a fast in solidarity. When Gandhi learnt of it, he wrote to Nehru:

Upavas chhoro.

Bahut varsh jiyo.

Aur Hind ke Jawahar baney raho.

‘End your fast.

Live many a year.

And be Hind’s Jawahar forever.’

This is rhymed prose, un-intentionally perhaps, but unmistakably so, with an o-ending to each of the three lines. Each last word is of four syllables. The whole passage is metred, with five feet in the first two sentences, ten feet (exact double) in the last. Drawn in markings, it would make a very symmetrical kolam:

And each line concludes with an exhortation: chhoro – terminate or end, jiyo – live, raho – abide. Or, in other words: do, accomplish, be. With the last one – raho or ‘be’ – being, in content, a summiting. The shortening of Jawaharlal to Jawahar is also significant. The full name would have stretched the metre to breaking, and the meaning to an absurdity. He meant Jawahar in this line to mean Jawahar the man and Jawahar the gem.

Does that make Gandhi something of a metrical writer, a versifier? No! It does not. But it certainly points to an inherent sense of rhythm in his style, a natural bent for metre which in turn points to a natural sense of measure, of an inner order of which ‘non-spillage’ of ideas or expressions was part. And, so one notices in Gandhi’s sparseness its own Attic aesthetic. Does that make Gandhi a poet hidden in a prose-writer? In a Tamil response: Sariya pochchu, No! Not at all. But it does make him a user of words a notch beyond the routine, beyond the utilitarian, beyond what may be called the purely functional. He uses his words with an eye and an ear to their sound, even, surprisingly, to the music in them. A literary aesthete in the style of Tagore he is not; owner of a distinct and impactful style, he is. Gandhi economised his use of words to sharpen his message, he did not prune their register to crop grace out.

LILA: Speaking about ‘registers’, what could be a Gandhian strategy that an Indian writer could adopt today to connect with the country’s diverse demography, and communicate effectively, especially with the youth whose pursuits and goals are increasingly defined by capitalist and consumerist industries and not by their own rich cultural backgrounds?

GG: By using what used to be called ‘the Indian vernaculars’ more and more, by which I mean a vocabulary the average Indian would be familiar with. Part of a simple literary style’s attributes has to do with the accessibility of its vocabulary. Gandhi’s Gujarati leaned towards the language of daily speech, inclusively, rather than that of the library, exclusively. Opening his South African memoir at random, on page 172, we find the following words of what may be called Hindustani (Persian, Arabic or Urdu admixed) origin: shahar, khabar, jang, lalach, nuqsan, nasib, marhum, bahosh, bahadur, salah, qaum, darya. He could have, instead of these, used nagar, samachar, yuddha, lobha, nashta, svargiya, sachetan, sahasi, mantrana, samaj, samudra. Why did he not do so? One reason, of course, is that the words he did use were in the standard Gujarati register. He did not import them into his writing. He was using what was being ordinarily used. But the same register also had Sanskritic synonyms for those very words which he could have easily used, instead. Did he not know them? Of course, he did. On the same page he uses other Sanskrit-origin words with the same ease: sabha, dhan, akshar, sankhya, pratipaksha, pradhan, shanta, dhiraj, varga, kutumba. The point is that his style of vocabulary was not ‘extreme this or that’, not ‘one way or the other’. It was as he was, in a contemporary phrase – inclusive, instinctively inclusive. He could move from one register to another depending on his instinct to pick the most effective, the simplest, the most natural conveyance. He was no pedant; he was, simply, himself, Hindustani, Indian. One might add – us zamane ka, Hindustani, Indian. Today, one would, looking over the shoulder, say us samay ka Bharatvasi.

LILA: Do you think there is a transformative role that the study of Gandhi’s language can play in the society today? In this age of advanced technology, how would you envisage a public movement for that?

GG: Reflecting

on Gandhi’s style of speech should be part of studying his ideas and it only

follows that anyone thinking of the ‘daridra’, even when hyphenated from

‘narayan’[1], would find it invaluable.

Directness, with the brevity and urgency of a telegram or – now – the tweet, cannot be part of the tools of a ‘movement’

but can be a methodology to turn to. JP did that to great effect in the early

1970s. Those diametrically opposed to Gandhi, though co-opting him, (and,

likewise, doing the same with Ambedkar) are employing the ‘direct’ approach

with social media dedicated to their service.

LILA: How do you see the future of Gandhian Studies? How can the academic centres studying Gandhi communicate and connect with the modern society at large, plant the seeds of his ideas and grow them?

GG: ‘Gandhian Studies’ are part of curricula and course options in many institutions of learning. But his ideas and methods of communication are alive outside of those centres, earnest and often rewardingly energetic as these are. And this ‘outside’ is the large arena of social and economic action, of which the recent-most example was the ‘long march’ of peasants from Nashik to Mumbai. Whether the marchers mentioned Gandhi or did not, is immaterial. Their largely ‘silent’ protest was in itself a language, a vocabulary of which no-violence was the greatest feature. I have said, as the reader may notice, no-violence rather than non-violence. This is to free that vital concept from the hide-bound doctrinaire ism-ism of ‘non-violence’.

The paragraph in his autobiography that describes the ‘turning point’ in Gandhi’s life, transforming him from a barrister no one noticed to a leader none could ignore, is worth our attention. The ‘train incident’ as it is called, in Pietermaritzburg, has been vividly portrayed by biographers, illustrators, film-makers. Its dramatic core has been mined to the full, over-mined. But the protagonist himself devotes no more than half a dozen almost incidental lines to the episode’s factual re-telling. In a chapter in his autobiography (written as we know, originally by him in Gujarati) that is called Pretoria Jatan, or On The Way To Pretoria, he says matter-of-factly that, after he refused to leave his first class compartment, the disapproving railway official got a constable to move him.

Sipai avyo.

Tene hath pakadyo ne mane dhakko marine niche utaryo.

Mahadev Desai has rendered that, accurately, as

The constable came.

He took me by the hand and pushed me out.

That is about all there is, in Gandhi’s words, of the actual ‘assault’. No drama, not to talk of melodrama. No tossing out, pitching out, hurling out, throwing out, tumbling down, no abusive words flung at him, no stoic silence in return described. Nothing of any hurt sustained, either or attire dirtied, torn. No description of trauma, shock, rage. No ‘hu-ha’. Just those two austere lines. Typical Gandhi. Factual as factual can be. Actual as actual can be.

But – and this has gone un-noticed – there is style, one may even call it the technology of art. Unintended again, perhaps, but there.I cannot but point to the three yo-s in it.

Avyo

Pakadyo

Utaryo

With another o between them, exactly as in the sequence of happenings – dhakko. That nine word line with its emphatic yo ending words – avyo pakadyo dhakko utaryo – gives in Gujarati Marconigram the entire episode, the experience, the outrage which not only saw a lawyer fall down and a leader rise in his place but road-signed the commencement of global de-colonisation itself. Truth does not need dramatization. It only needs narration. Truthful narration. A banyan grows from but one seed.

LILA: How do you think Gandhi would have responded to our times–what language would he have used, being the extraordinary tactician that he was?

GG: How would he have responded to our times? Exactly as he did in his times. As a communicator he would have been classical, modest, clear and altogether masterful.

Classical in the sense of being:

- Derived, taken down, transcribed, imbibed, assimilated, absorbed from old tradition.

- Unsparingly adherent to the given matrix.

- The result of lessons, both pedagogically received and self-taught.

- Learned through ardour and effort, not ‘picked up’.

- Self-denyingly conservative in form but audaciously original in content.

Modest in the sense of being:

- Free of all opacity.

- No sententiousness.

- Avoiding of hyperbole.

- Zero rhetoric.

- Absence of ornamentation (no gamaka, rarely a neraval and no kalpanasvara)

Clear in the sense of being:

- Direct.

- Using, invariably, the first person singular.

- Propositional, even when propounding a theory.

- Moderate in the employment of quotations.

- Economical if also telling and educative in the use of legal and Latin phrases.

And altogether masterful by

- Packing large messages, deep thoughts, into few words.

- Appealing to the reader’s veracity, not vanity.

- Stressing his own vulnerabilities.

- Claiming no infallibility.

- Stating his intention to proceed with or without the reader by his side.

Gandhi wrote because he needed to, not because he wanted to put pen to paper. He wrote because writing was part of the activities that grew around his convictions. To describe him as being an extraordinary tactician is correct, but only partially so. He was an extraordinary technician – of India’s complex circuitry.

[1] daridra-narayana (literally, ‘the Lord in the form of the poor) is an axiom enunciated by Swami Vivekananda, espousing that service to the poor is equivalent in importance and piety to service to God. He referred to feeding the poor as “Narayana Seva” and urged his followers to do “Daridra Narayana Seva“—service to the poor as service to God. The term was popularized by MK Gandhi.