LILA: Thank you for participating in this conversation. We would like to talk with you about your time as the editor of the arts page in Economic Times, which is an interesting period to unpack and understand the relationship between media and public intellectual engagement. Can you tell us of the kind of pages that were curated as part of this project, especially in terms of how it started and what the vision behind it was?

The idea of The Economic Times [ET] having an arts page, of course, antedates my joining the paper. Around the year 1989, I think, the Times of India Group, began sensing a change in the winds of financial policy, the pressure exerted by the International Monetary Fund on the Indian economy, and correctly anticipated that economic liberalisation was around the corner. The Economic Times was a staid and dull paper then. It had mostly stocks pages, corporate profiles and government pull-outs, and was useful only for some bankers, academics and those who played the stock market. So, the Times Group – Bennett Coleman & Company Ltd. – decided to revamp ET to prepare for the anticipated liberalisation. They pulled in T.N. Ninan from the India Today group [or was it Business World?] to be the new Editor of ET. They looked at various good, workable models for financial journalism from around the world, and found the model of the Financial Times, London to be the most attractive. It is a pink paper which also covers non-financial subjects, has fantastic weekend spaces and, of course, the daily arts page. So, that was the module on which the re-vamped ET was built. It was a clever and far-sighted move, because, while the actual liberalisation happened only in 1991, already by 1990 the paper was ready for it. They had in place a stable of extremely good and dynamic young editors looking at various areas, including science and technology, public health and education. The intent was to not get confined to just the financial space, but look at the media landscape more broadly.

I joined ET as the Arts Editor in 1991, after a long, deliberate hiatus from mainstream journalism. What I inherited then, was a thrice-a-week arts page – Monday, Wednesday, Friday (later rescheduled to Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday) – and a Sunday page that was supposed to be more relaxed. The excellent template had already been laid by Shikha Trivedy and, later, Vikram Sundarji. The format too was already set, because ET had been re-designed for an online printing process (among the first such papers in India). So there was a predetermined design for each page. Even before I joined, I had researched the scope of an arts page in a hardcore financial newspaper in India and who its readership might be. The layout of the page wasn’t very appealing to me because it was rigidly formatted and seemed dry and lacking in suppleness or playfulness. The articles and visuals seemed too fixed and pre-set, leading to a repetitive look.

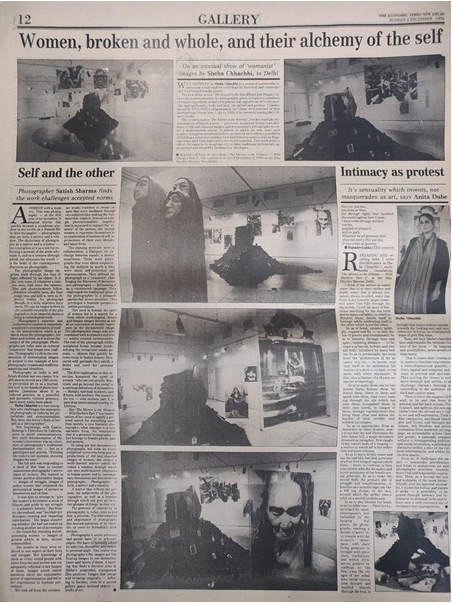

ET was considered an elite and ‘high end’ paper then, read by captains of industry, bankers, corporate honchos, academics, researchers, et al. But, in my survey I found that it had a wider, eclectic readership – it was also read by trade union members, activists and scholars because it carried information and figures that were useful across the board, for a wide range of people. So, very slowly after I came in, I decided to do two things – one was to cover the arts/culture terrain from a critical, subversive perspective [content that would be unfamiliar and, perhaps, even uncomfortable to its corporate readership] that would speak directly to the ‘activist’ reader; and, secondly, work against the grain of the design itself so that the ‘high profile’ reader would get attracted to a desired for internationalist look.

It had to be done slowly. It led to a few stand offs with the extremely talented design team, who thought I was intruding into their territory. But having apprenticed with the legendary Indian designer Dashrath Patel in graphics and book and poster design for over a decade by then, I had enough bandwidth to hold my own and explain my intent. Slowly everyone got the point of what we were trying to do and the initial friction settled into creative camaraderie. While one could make a difference with the content straight off, it took about six months before these four pages a week began to stand out as special statements. It became a thought-out package that combined content with form and style of writing.

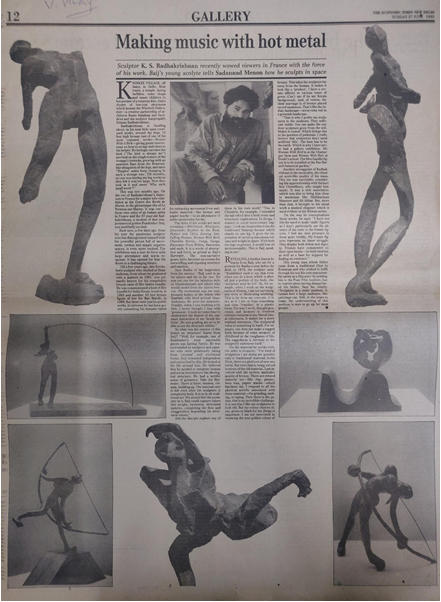

The other thing with Economic Times was that those days, it was published out of seven centres around the country – Delhi, Bombay, Ahmedabad, Kolkata, Kochi, Madras and Bangalore. Ninan was good enough to sanction my travel to all these centres and reach out to artists, writers and critics I knew there, seeking their contributions. Soon, the arts page in ET stood out as a national page for the arts, unlike in Times of India, Indian Express, Telegraph and such, whose arts sections remained city-centric because of geographical or locational reasons. ET tried to make a difference by looking at the national landscape – from literature, to visual arts to performing arts, photography, architecture, crafts, heritage and policy issues.

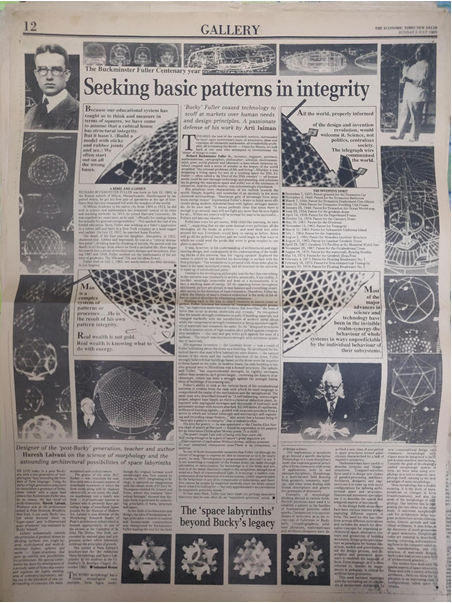

By 1993, the ‘Thursday Arts page’ had morphed into India’s first broadsheet page for ‘Design’. It was the first time in mainstream Indian media that design issues were being debated, with some of the best known names in the field from NID, IDC and abroad, contributing. A year or two later, we also creatively re-jigged the ‘arts’ space to include hard-hitting pieces on problems posed by big dams, by nuclear technology, by restrictive education, the eroding of the electoral process and so on.

LILA: It must’ve been interesting to find out that there was an eclectic audience that subscribed to ET. Did this change the conceptualisation of the art pages for you, from what you had inherited?

Sadanand Menon: Yes, it did, in the sense that it suited my temperament and my own political outlook. After the economic liberalisation happened, it was very clear that ET was going to be pro-corporate, pro FDI and pro-divestment of PSUs. Editorially, it was asking for removal of all trade restrictions for a free and liberal economy; it was on the side of tax cuts for the big fat companies. But ET also had a very interesting stable of editors. Out of the nine, at least three were pro-Left, two or three were somewhere in the centre, and one or two were conservative. But it carried opinion pieces by a large number of Left-liberal economists.

I myself was inclined towards a progressive and Marxian ideology. I would pitch for artists, artworks, events and trends that had a critical content and sought out cultural work which had transformative political intent.My contributors and writers were also more or less selected on that basis. The edit meetings at ET were quite fascinating because it was always a tussle of ideas. Slowly, probably for the first time, the other editors took note of what was happening in the arts pages and either supported it or wanted to contend with it quite aggressively. That sort of confrontation was good. It helped considerably that I had some extraordinary support from my own editorial team – from assistant editors to sub-editors to writers – a very young set of colleagues, still learning on the job, but who had implicit trust in what we were doing. It is no surprise that each of them, in the past twenty-five years, has gone on to win accolades and awards in various branches of the media.

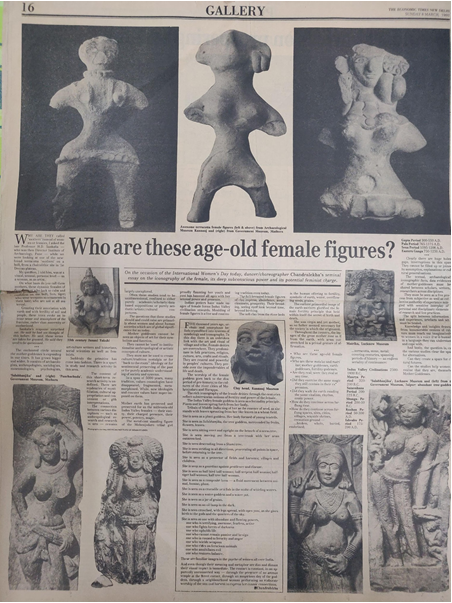

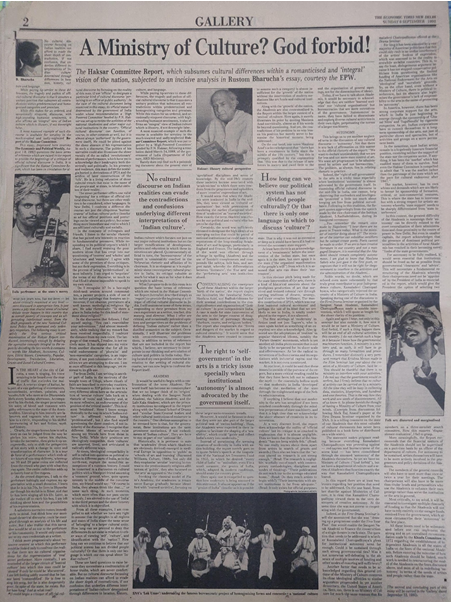

I also adopted a consciously cross-disciplinary strategy for seeking contributions – historian Romila Thapar, being familiar with pottery, wrote a terrific piece on ceramist Gauri Khosla; art historian Geeta Kapur did a deeply insightful piece on filmmaker Kumar Shahani; dancer Chandralekha did an inspiring piece on excavated terra-cotta female figurines; poet Pria Devi wrote an evocative piece on the ravages of plastic tourism at the Gangotri glacier; dramaturg Rustom Bharucha did a clinical dissection of the Haksar Committee Report; and so on. We were constantly looking for ‘experts’ from one field who wouldn’t hesitate to come out of their own discipline and explore a related space. The results were astounding in the kind of richness of insights that emerged.

LILA: How do the newsrooms then compare to those of today? It seems like most media houses today have a singular political or ideological mandate, without even an internal diversity of perspectives… How does this compare to the way you described debates in the newsroom?

Sadanand Menon: I don’t think you can even begin to compare the two, because it was a particular period in Indian media history when debate, discussion, diversity, contention was at the core of the editorial raison d’etre. Besides, almost every paper had arts pages and arts editors who were well known and distinguished in their own line – the Telegraph had a 12-page weekend pull-out that was edited by Chidananda Dasgupta, the well-known filmmaker, writer, and film critic; the Indian Express had an 8-page weekend pull-out that used to be edited on a turnkey basis by Tarun Tejpal and his team; the Times of India Bombay had Shanta Gokhale as their arts editor, and so on. They all brought a distinct approach to the coverage of the arts. This began to change somewhere around 1994 when the effects of liberalisation began to sink into the media.

Among the first effects was the arrival of big advertisements. There would be these fantastic, eye-catching half-page advertisements, mostly for cosmetic brands, created by a group of people – visualisers, copy editors, designers, photographers – all working with a big budget, and the article and layout that would appear above it on the news page would be no match for it visually. Gradually, the advertisers began imposing demands. Their logic was that if they were paying several lakhs and placing an ad which pitched for the ‘good life’, they didn’t want the mood spoilt by an article above it that talked of starving peasants or poverty. Not only the advertisers, but even the in-house management team would tell us to carry ‘sunshine stories’; that the news should be like froth, ‘what rises to the top’; or that the paper should be ‘cuddly’ like a ‘teddy bear’, so that you ‘felt like taking it to bed with you’. Whatever was prickly could be tucked inside.

The ET sold at Rs. 5 a copy. The management philosophised that those who could afford such an expensive paper would be readers from an elite background, who had a certain vanity about themselves – about being a person of the world, knowing your art, your cinema and your music, etc. The arts pages were cynically meant to cater to this vanity. But post-liberalisation, with the arrival of big advertisement in media, the cover price of the paper began to be sliced. Simultaneously, attracted by these advertisers, the competition in the market also began to grow. It was no longer just Economic Times – there was also Financial Express, BusinessLine, Business Standard – and all this competition led to a price war. This peaked somewhere around 1994, with ET drastically slashing its price to Re. 1 per copy. When they did that, a kind of a turnaround in their attitude towards the nature of the paper also happened. They decided that, while a Rs. 5 per copy newspaper was for the elite and catered to their vanity, a Re. 1 per copy was something that everybody could buy; it would be more popular and be consumed by a lay readership. These new readers would not be the gallery going typesor be aficionados of classical music or dance. So, if the arts pages had to continue, they would have to dumb down and become more like an ‘entertainment’ page – going to popular culture, mainstream cinema, Bollywood, etc. Even the excellent science and education pages in ET were deemed to be redundant and, one by one, they started pruning these. The management was very clear that the focus had to be entertainment, whereas we, who were producing the pages, were very clear that it had to be serious and engaging with social issues and so on. This tussle lasted roughly a year before the interference became so much that I decided to move out.

Meanwhile, this also had a peculiar domino effect. All the other papers noticed the major track changes in the Times of India group and, probably, imagined there to be some great marketing wisdom, and profit-motive behind it. So, one by one, other papers also dropped their arts pages.

What happened in that period then, roughly between 1994-1996 was that, first of all, the arts pages were abandoned by the entire Indian print media. Secondly, we saw the last of this character in the editorial team called the ‘Arts Editor’. It is interesting that from 1996 till today, there hasn’t been any media house that has recruited an arts editor. The only paper today that retains a considerable amount of space for features is The Hindu, but even they don’t have an arts editor.

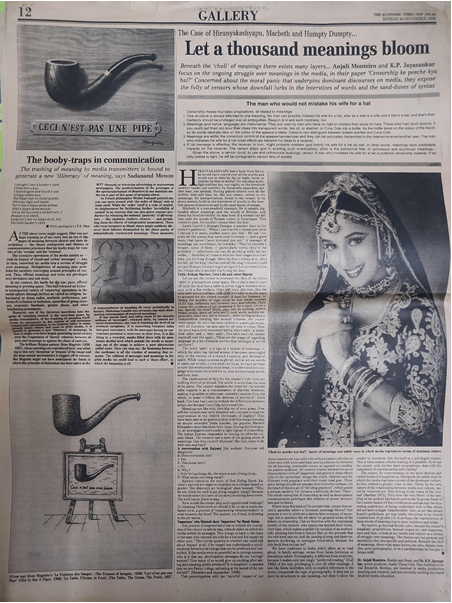

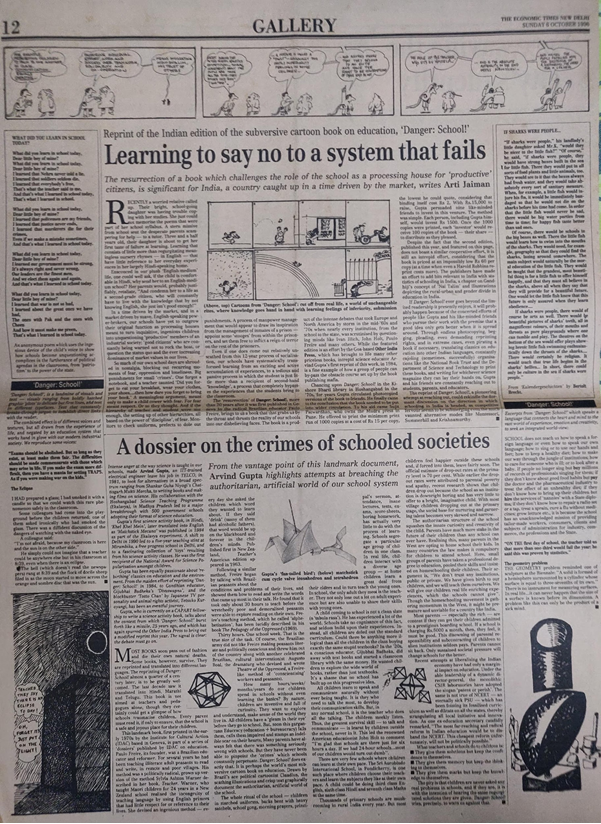

LILA: If we look beyond the market forces, what the art pages did was also present a uniquely non-violent way of discussing different political conflicts and social issues – for instance NS Madhavan’s story about the Babri Masjid, The Blue Pencil, or the full page cartoons from different cartoonists commenting on Jayalalitha’s censorship of the media. Do you think there is a space for such a medium to emerge again, looking at the quality of public debate these days?

Sadanand Menon: There is really no comparison, because at that time it was very clearly about being combative, being adversarial, being oppositional. There was no question of being soft and admiring. It was very clear that your role as a media person was to talk to power, whether it was by producing material on art, science, education, politics or finance. But post-1996, all that began to change.

It was also the era when electronic media was storming in, in a big way, and redefining what the print would be, with its 24/7 news reportage. At that time the leading channels still had a certain social aspect to them: they were covering rural distress, culture, health issues, etc. But slowly all that got bundled into this one blinding thing called entertainment. Even news coverage has got a sensationalist, entertainment format now. So the print media was left holding this baby with very little clue about what to do. By the time we entered the middle of 2000s – around 2004-05 – the digital media had taken over. Obviously, the print media is on the back foot now and is not able to contend with any of this. Thus, the idea of news content and the oppositional attitude is continuously getting diluted. The public discourse in the mainstream media is unabashedly flattened and uni-dimensional now. I am not saying this is across the board. There are exceptions everywhere. But the mainstream media is not the space to develop a nuanced public discourse anymore. There is no point lamenting over it. That’s the way it is.

Most of the oppositional discourse today is building on other platforms – like Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, etc. And, of course, on the new web portals. The more serious discourse, particularly in the arts, has been pushed into niche platforms. That is where the tragedy of the whole thing lies, because we have this huge mainstream media – around 1.7 lakh print publication in India, some 800 channels and over 500 broadcasting stations and all that. And when we realise that almost none of them gives space for a discourse around the arts, we surely are in a strange situation.

At the same time, in the last 25 years – from when the arts pages ceased to exist in 1996, to now – we have had a tremendous growth in the market for different art forms. So, for example, the Indian visual arts market may be worth around Rs. 2,000 crores, but it is not able to support good arts journals or magazines. You hardly have 2 or 3 arts journals of limited periodicity in the country. So you have this huge financial market without any monitoring, comment or critique. It’s the same thing with the publishing industry – a Rs. 30,000 crore industry with hardly two serious literary journals in the country. Performing arts too – music, theatre, dance – a big industry, with no journals to track the many developments happening there.

LILA: Well, one of the issues with such serious art or culture journals is that they tend to get limited by a niche audience, and are therefore not able to impact the larger public discourse. Since there seems to be a space emerging for such content to grow, do you think there is also a need to bridge the gap between different types of intellectual publications and the general public? How can we do this?

Sadanand Menon: In the larger landscape in India, most of the arts are seen as being elitist, too abstract, and cut off from people’s lives. Some things like the Kochi Biennale attract quite a few people, but it’s very slow. It’ll take maybe 10 more years for something to emerge out of that.

However, over the past decade and more, several universities across the country have established departments in ‘Arts & Aesthetics’ and considerable amount of new research has started emerging, contributing to new directions in the arts as well as a more informed and complex layer to the discourse around the arts.

My take on this, though, is slightly different. I was recently [May, 2019] at a very interesting roundtable in Singapore, which was looking precisely at the crisis of arts reportage in the media in South East Asia. There were art critics, writers, art editors from Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Philippines, Myanmar, Indonesia, Singapore and Japan. I was the only one from India. Almost all of them [except in Japan] have to deal with the issue of direct censorship in their countries. They are all ruled by oligarchic dictatorships or the military and they are all under threat most of the time, even if they are writing about the arts. Some of them have been to jail; some have been harassed and persecuted; some have been banned. But precisely because of that, their connect with their readership is much stronger. The readership needs them to speak a certain language of honesty and truth. And they have also become very innovative in the face of censorship – how to say things that dodge the censor and, at the same time, are obvious to the reader. This holds true for their artists too, who are constantly fighting to slip under the surveillance radar. So that is a very dynamic and, at the same time, very hostile situation, which we are yet to experience in India.

My hunch is arts writing and the need to engage with society and politics will increase and become relevant only when such a situation develops here. And as things are, it is going to develop soon. This whole pretence of a liberal atmosphere for the arts is just that – a pretence. The long, restraining hand is everywhere. I seriously believe that majoritarian communalism and the onset of an illiberal democracy in India almost coincided with the guillotining of arts coverage in the Indian media. It’s a research project for someone to do. There is also large-scale, prevailing illiteracy about contemporary developments in the Indian arts scene. Today you can name at least a dozen and more Indian visual artists who have done brilliantly, have had exhibitions in India and abroad, who are also selling very well, and have received critical acclaim abroad, about whom Indian media has not written at all, and the Indian audience and readership stays uninformed about it. So is the case with contemporary dance, or music. Many new things are happening, but without any requisite or reflective comment in the media.

The other significant factor is the de-skilling in arts writing that has happened in these 25 years. When the arts pages ceased, it also pushed out an excellent cadre of writers on the arts, who progressively wandered off into other aspects of writing. With no space to write on the arts during a boom period in Indian arts production, a vital historic continuity was snapped. Only this can explain a certain channel breaking news of Girish Karnad’s death as “the ‘Tiger Zinda hai Actor’ has passed away”.

I have conducted an elective course in ‘Arts and Culture Journalism’ at the Asian College of Journalism, Chennai, for 18 years. And I have always introduced the course as a ‘mythological’ course, since there is no real space for it in the media. Of course, some students have pursued this path diligently and have made their mark in the limited space available.

The bridge issue then becomes a difficult thing, if the audience is not interested and is not clamouring for it. I remember, over four decades ago, when I was working in the Indian Express, Madras, they had forgotten to renew their contract to the Tarzan comics – a daily, 4-frame comic strip on the last page. On a particular day, it stopped appearing. Within 3 days, over 40,000 letters poured in asking for the Tarzan comic to be restored. So the readership can respond like that. But there is no commotion demanding the return of any arts page. To be fair, when the ET arts pages were cut, there were over 700 ‘letters to the editor’ from artists across the country, seeking its restoration. But that did not have the necessary ‘critical mass’.

LILA: This kind of goes back to the point you were making earlier, of arts being considered something that is for the elite.

Sadanand Menon: Even then, the Indian elite can be a good 10 million people or more. That should be enough to make people rethink their strategies and policies.

LILA: Do you think people have lost that kind of attachment or investment in social issues? These days we mostly see heated, insubstantial discussions on television, all aimed at getting higher TRP ratings. What has happened to the media? Why has it lost the sense of responsibility to curate nuanced discussions in the public space…

Sadanand Menon: I won’t make any general comment on that. But one thing is clear, and I have been saying this for sometime now at different venues – since the time those arts pages were knocked out from the Indian newspapers, as far as I am concerned, that was the beginning of the squashing of democracy in our subcontinent. I personally believe that a society that is not able to look at the creative forms around it and respond to them outside of the market space is a seriously deficient society that is getting to be highly monolithic. For me all this represents not merely a deficit in art writing; for me it’s a democratic deficit.

Now, with the BJP government in power, which has made a pastime of capturing institutions, we have this amazing spectacle of spaces like the National Museum, the National Gallery of Modern Art, the Lalit Kala Akademi, Sahitya Akademi, and so on, being governed by people who hold one kind of political viewpoint. Either these institutions are being converted into mono-dimensional centres that promote only the majoritarian view, or they are being made dysfunctional. There is even the expressed fear that all these institutions are being deliberately devalued to facilitate eventual private take-over. This is happening without challenge. There’s no media space that can challenge it. We don’t have sufficient data or research to evaluate what the effects of this are on the institutions, or on art practices in general. So it is an assault on democracy as far as I am concerned. The media is a victim of that as well as a means.

LILA: We may not have data on how it is impacting, but we surely know it is impacting. What is the kind of resistance that can happen anyway? Is there a role the media can play in this?

Sadanand Menon: At the moment I don’t think the resistance can come from the media. It will come from the art community. I’m sure there is enough spirit, energy and talent in the Indian art community to speak back and fight back. The media will not be around to record it and transmit it, but nevertheless it’ll be happening.

What is also quite important in the current time is that reflection and theory around art production is going to increase. Much more sharp and critical, theoretical production is going to happen, I think. We have always seen in this field, that at some moments the artist and arts are ahead, and politics and theory follow, and at some other times, theory is ahead and the arts follow. I think today we are at that stage when more critical theoretical production is likely to happen, even as the arts get muted by censorship and other factors. Censorship today comes not just from the state; it also comes from the street. You get 10 people to stand with sticks in front of a gallery and say ‘down with this artist’, and they remove the work of the artist. The police won’t support you; the state won’t support you. Self-censorship comes from both these directions. Some artists will risk it and do what they want to do, but I think the more radical work will be theoretical in the next few years, and eventually that may become the bridge between the media and a new readership/viewership.