LILA: You have closely studied the impact of the modernist development paradigm on the villages of North India. Your paper titled ‘Emergent Ruralities’ draws a very interesting comparison between two villages of Haryana between 1988-89 and 2008-09, tracing the social and economic transformation as a result of the green revolution and industrialisation. What is the difference in the approach that you bring when compared with a vertically specialising economist or sociologist studying this phenomenon?

Surinder Jodhka: One of the issues that has plagued the study of agrarian life in India is that one tends to think of agriculture as a sui generis process – either you think in sectoral terms, like the economists do, or in evolutionary-developmental terms, where it is seen as a stage in the evolution of societies. The primary problem here is the preconceived view of the rural and agrarian which comes to us from what one would call a post-enlightenment framing of the world – that you have different levels of evolution and the modern life is what everyone is trying to achieve in one form or the other. The rural gets essentialised in this view, often conflating it with agriculture – it is assumed that everyone living in the village is engaged in agriculture, and that rural is nothing but agriculture. Even somebody like Gandhi, in a way, is negotiating a similar narrative when he claims that India is a land of villages, where ‘the rural’ as a specific entity is taken for granted. This has empirically never been the case. If you look at social life, it has always gone together. The moment agricultural societies come into being, they also produce certain kinds of state systems; the state systems in turn begin to shape agriculture, and the town becomes an essential part of the same social formation.

When I was doing my study in the 1980s, we were thinking along similar lines, but when I revisited these villages in 2008-09, my perspective underwent a complete shift. As a result of the neo-liberal rural and urban economic imagination as well as a more democratic political imagination that emerged during the Nehruvian era, we were talking about caste much more by 2008-09; we were talking about inequalities in a language very different from simple class/land-based inequalities; and with globalisation on the rise, we were also thinking of the economy much more globally. Labourers were beginning to find opportunities outside the village and did not like to remain tied to agriculture, which to some extent empowered Dalits and helped them move out of the village. The green revolution also enhanced the demand for labour and set in motion a process of change wherein labour from Bihar and eastern U.P. started to migrate to Punjab and Haryana in a bid to run away from local contexts of hierarchies. Until the 1980s, this was seen purely in class terms, but by 2008-09, it began to be seen through the lens of caste as well, as evidenced by the rise of Lalu Prasad Yadav in Bihar. So such a study helped me decentre agriculture from the notion of rural. That became possible only by looking at the larger process through which we visualise rural economy, life, occupation etc.

Besides caste, the question of gender also acquired centrality in social sciences during this period. Gender is indeed an important aspect of rural life. As a male researcher, it was hard for me to speak to rural women, and some people even criticised me for being gender blind, which I do not deny… But I spoke to lots of people, and question of gender did come-up. For example, during the 2008-09 fieldwork I observed that in many landed families the daughters were being allowed, perhaps also encouraged, to study even if took them away from the villages. If they showed enough promise and capability, they were allowed to stay in hostels as well. That was also the time when the question of honour killing became a major problem, and it was very easy for me to understand why. These were young girls who were very aspirational and had done well for themselves, while their brothers hadn’t. So this new question of compatibility and new imagination of sexuality started to come up. These young, independent women wanted to choose their own partners instead of having their families decide whom they would marry, even if the chosen person wasn’t from their own caste or wasn’t acceptable to the family. So that was a very important thing that came out.

These kind of multifaceted realities of rural life I was able to bring out because I was not constrained by the earlier economy-centric frameworks. I think such an open-ended and grounded perspective makes a lot of difference, and when I look back, as you are asking me to do, those are the things I would want to talk about.

LILA: A very interesting insight to come out of this study was also about ‘ontological insecurities’ emerging amongst the people of these villages due to the flux in social structures. What does ontological insecurity mean and how does it play out?

SJ: In the last part of Emergent Ruralities, I talk about the phenomenon of ontological insecurities. That was a very important opening for me into the question of religiosity in the villages. I observed through this study that human beings are not really working in agriculture or the rural economy only for their livelihoods. They also want some kind of meaningful community with which they can relate. And, they also develop their own aspirations, individually and collectively.

By 1990s and 2000s, what begins to happen is that land holdings start becoming much smaller. Land is generally divided across all brothers in most of India. On an average, families in rural households have at least three to four siblings. So, even if you have 50 acres of land, it would be left to less than 15 acres by the time the next generation comes. This was very significant. In two to four decades, the land for a large landholder went from, say, 80 or 90 acres to just seven or eight acres per brother. This also has a gender effect in terms of the sex ratios becoming a problem. Given the growing value of small families, farmers wanted to have only one son and did not seem to mind if they had no daughters because this helped them keep the holding size stable.

And then you also have the new global consciousness emerging at the same time. A farmer’s life is very difficult, unromantic and rough. So now, there is a generation which doesn’t see its future in the village and wants to move out. They would go to Spain, France, England, Canada, wherever they could get in and find some job.

Now, for those who have no aspiration to go beyond the village, the village social life becomes very fragmented; so much that they don’t even trust their brothers. In the paper, I also write about how two brothers going to the same place will go in two different vehicles. There is no community life anymore. So, you start looking for a new community where you can feel comfortable. That is the ontological insecurity, because people become very competitive. Money culture comes up, so if one brother is slightly richer, he would want to show off his wealth by buying his child an expensive car or mobile phone, and then the others will obviously not feel good about it and only get envious.

So there is this thing happening which is more existential. There is an attempt, then, to come together. Members of dominant castes who are left with very little land see their existence as not being very different from those from the lower castes. In some cases, they also make friends with members of the lower caste if they went to school together. So, they all decide to sit together in the tractor and go to the Sirsa [Dera Sachha Sauda]. At Sirsa, they are away from the village and away from the local caste atmosphere. They feel like brothers who can sit together and eat together. This sense of community and bonding, which all of us need, starts to emerge through these friendships and new kind of relationships. That’s how Baba Ram Rahim becomes useful to people. People think it’s a religious thing, but it’s more than that.

LILA: Let us talk about the rise in aspiration first. While you talk about how the rural has never existed in isolation, you only observe these aspirations during your second visit to the villages in 2008-09. How does this come to be, and what kind of impact does this have on the village economy?

SJ: This is a very important point because in the 1980s, the people who came from big landed families were looked up to by everyone. You would have seen in Punjabi music videos, when a Sardar or Jatt comes in a tractor, the symbolism of the tractor is very prominent. There was a sense of pride in “Sadda Pind” – “Pind” is a place where authenticity is. Then, by 1990s, you have the shift where the urban middle class becomes the norm. With liberalisation, the valued jobs become those outside the state sector as people are offered much higher salaries than that of an IAS [Indian Administrative Services] officer or a professor. I remember there was also a big movement where people started to migrate to the United States to become software or computer engineers, and study Masters in Business Administration. This was also the time when rural begins to feel a new crisis.

This crisis is at three levels – first is that the state doesn’t need agriculture any longer because it is opening up and you can import things if you require. While the green revolution period had positioned agriculture as the saviour, now it becomes a burden, which is finally translating into the passage of the three recent farm bills. It starts right then in the 1990s, when they wanted farmers to be more independent because they were beginning to be seen by the state as “a burden”. Agriculture was not talked about in a celebratory way by the state anymore, and also with the rising middle-class salaries, people coming from rural areas into the city started looking up to the middle class as role models.

Now, this was a different kind of middle-class. Earlier, the Nehruvian middle-class had been sarkaari babus, but these were middle classes in the corporate sector who were global fliers working in Singapore and simultaneously in London and California. They had an office coming up in Gurgaon; Bangalore came up as a global city, and the mobile phone began to connect people to different kinds of mediatisation. Politics was mediatised, culture was mediatised, your religiosity was mediatised, which led to the making of a new kind of self; a self that was very aspirational in every sense of the term.

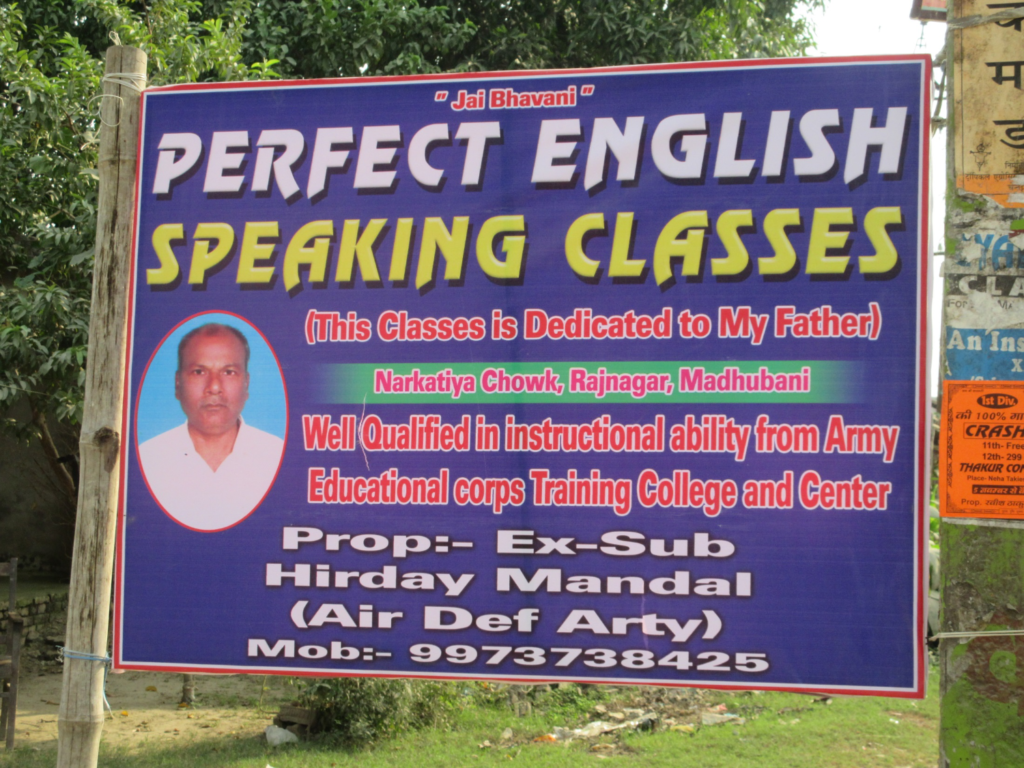

We also observed this in Madhubani, in Bihar, in 2016-17, and it was very interesting because everyone was mobile. This mobility made them feel like everything was possible. I think that was the moment caste became something else. Individuals and communities no longer felt tied to their caste occupations or constrained by their origin. This was a new aspirational revolution where young people began to move away from these structures.

LILA: At the same time this aspiration started to grab people’s imaginations, the empirical evidence from your research showed, a large number of labourers on the field remained Dalits and about 92% of the land holders were still dominant and upper caste people. How does that contradiction play out?

SJ: That’s where persistence comes into the picture. That’s the next phase of the story – the reproduction of caste. When you look at the results of high-end competitive exams in the northern region, the top 100 students are always Guptas, Agarwals or Sharmas – the typical names of North Indian upper castes. At the same time, the Patidar Patels, Jats and Marathas are coming to the streets, asking for backward caste status. What has happened is that these are aspirational people who have been uprooted from their earlier identities of being children of farmers. They continue to have their flights of land, but they want to come to the urban economy. Some of them made that jump between the 1960s-1980s by taking up all the new State sector jobs, which ranged from State administrative officers to bus conductors and constables. But their children are more aspirational. They have engineering, business administration and all those degrees, but by the time they enter the job market, the space is already saturated and, in some cases, even shrinking. There aren’t too many new jobs, and those that are available go to the already-established middle classes, which are all urban upper caste people who have social and cultural capital. In my own work on corporate hiring, we saw how caste gets reproduced in different ways when hiring managers assess the soft skills of the candidates. If you grow up in an English-speaking family, for instance, you grow up in a particular manner that shows that you belong to a certain class/caste – what we call Habitus. You inhabit that space. Due to a lack of these soft skills amongst the aspiring groups, when they apply for jobs, they get peripheral jobs like that of security guards, or at the most, supervisor of security guards, and not the mainstream corporate jobs.

So when the top-end jobs don’t go to them in spite of qualifications, they realise that they can get into educational institutions like the Indian Institute of Technology instead. I talked to one of the Jatt leaders when they were agitating, and I asked “yaar itna shor kyu macha rahe ho, kuch milega toh nahi, OBC [other backward castes]mien jobs toh hai nahi” (why are you making such a fuss? It’s not like there are jobs waiting for you in the OBC quota), and he immediately started counting the number of OBC qouta seats that were vacant in IITs, which the Jatts could get. They know that there are no government jobs but at the same time they will get admission in high-end government-run institutions, because they don’t find any other channel to stabilise at a higher level within the urban economy. These are dominant castes which are upper caste in the rural sphere so they don’t want to settle for jobs that are low paying and carry low status. They realise that this would not really take them very far, and that is when this whole thing becomes very critical.

LILA: In recent times, we’ve seen a lot of news about an increase in atrocities against the Dalit community. Would you draw a correlation between this phenomenon and the one you just described?

SJ: That is a different story, a more complicated one. In rural India, for example, we pick up cases of violence because they’re reported in the media. And they deserve to be taken up; they are very significant because they reflect not just the local relation, but also the larger power structure. As we were discussing earlier, status hierarchies haven’t really gone away; landlessness is still kind of localised among Dalits and lower sections of OBCs; and there is a process of democratisation with fragmentation of these social ties – some of it gets resolved through the dheras and satsang but most of it becomes conflictual because there is a section among Dalits that is no longer submissive.

Despite the atrocities, I personally feel that there has been a kind of democratisation at the local level in the larger society. If one was to look at this sociologically or historically, there has already been a considerable renegotiation of relations. In the 1980s, for instance, if a Dalit got elected as sarpanch, they would still easily sit on the floor, but when a Dalit becomes a sarpanch now, they are far more assertive; some would even behave like the ‘Choudhury’ [upper caste]. The Dalits don’t really behave like Dalits, as they did in the past and the dominant castes are no longer dominant, as they used to be in the past (until 1980s). There is plenty of literature on how the rural power structure has changed. Also, there is a new kind of criminal economy that has evolved in parts of India. Anthropologist Lucia Michelutti in her work on this criminal politics talks about how caste matters, but not always. Sometimes even a smart Dalit can become a leader of the gang. He could also be a brahmin, like we saw in the case of Vikas Dubey from Uttar Pradesh.

LILA: Is this shift in identities and situating yourself within a transformational society a transitional phenomenon, where we might see another structure emerge? Where do you see this going?

SJ: I don’t really know, and I would not want to speculate on this because one needs to think of it empirically. Our sociological wisdom suggests that the shift happens from a communitarian life to an associational one, where people join collectives voluntarily. The rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party is an example of this, because it provides people a different kind of collective life – of being Hindu. Somewhere, this process is linked to the growing fragmentation of ascription-based collectives. You don’t really have that kind of education to think of Aristotle’s civic society. They’re looking for something which binds them together and brings value to their lives. In this particular case, you are also giving people a very concrete handle to hate somebody. It is much easier for people to come together through hate – when there is a common enemy, we can all be together and celebrate our togetherness.

LILA: At the dawn of modernisation and economic liberalisation, it was envisioned that caste would fade away with economic and subsequently social progress. From what we have spoken about so far, it seems that this has at once happened and not happened. Where do you stand in this debate about the relevance of caste today?

SJ: The concluding chapter of my book ‘Caste in Contemporary India’ attempts to answers this question. My take is that the way we theorise caste itself is wrong. Caste is not about a low stage in human evolution or simply a past tradition. Neither is the modernisation thesis right, which states that caste will eventually disappear with economic growth, or it would have disappeared by now had it not been for the quotas. Both these formulations are embedded in an orientalist view of India which assumes that there is something exceptional about India, most notably present through the institution of caste. For me, caste is a good way of thinking about ascription-based hierarchies, which have been present in most, if not all, societies and they continue to exist even today, even in so-called advanced countries like the USA.

Wherever you have a plurality of ethnic groups, they tend to be seen vertically or hierarchically, not horizontally. All societies change, but the new inequalities always have the pre-existing inequalities built into them. The new inequality that emerged with capitalism will not be, like Marx had said, radically different from pre-existing inequalities; they would instead carry those inequalities within them. A student of mine has done a PhD thesis on Agarwal Banias in Delhi. This group invested everything they had into converting their status from a mid-level caste to an upper caste through mobilising all kinds of ascription-based resources, like becoming active in caste associations, etc. Thus, caste is virtually everywhere. Ascription is virtually everywhere, and you don’t get out of ascription just because of a mechanical process of evolution or economic modernisation. Urban social life is also hierarchical, perhaps more than the rural life.

There is a myth created by the enlightenment that societies change from ascription to achievement-based societies. The ideology of European individualism is an attempt to tell us that we are not good enough; we are incapable of any kind of rationality because we are still not individuals; that as Indian scholars, we believe in societalism and our personalities are shaped by our caste and a protective sense towards our social structures. We need to abandon this enlightenment view of history or enlightenment view of the orient and the accompanying binaries. Caste should not be seen from a kind of teleological perspective that it is a particular phase in history. Caste is a form of inequality; a form of visualising differences which are ascription based.

LILA: For the individuals and organisations deciding market policies – for instance the recent farm bills that have been passed – how can insights like these help inform the direction and approach that the policies must take?

SJ: In the classical economics paradigm, if you want growth, some degree of income inequality is inevitable, but beyond a point it begins to work negatively. But inequalities will not reduce simply by reducing income inequality. Inequality is a thing that people love because of ascription. It isn’t impossible to get rid of inequalities or reduce them. If you have more people in the market as consumers, you have a larger field to find meritorious people in your population. So, again, it comes back to a very classical way of thinking about human development, that you need to expand the capabilities of your citizens, like Amartya Sen’s resilience model. You need to invest in your people, and that is something which only the State can do. The market by itself will not do this.

What we are seeing is that the market has captured the State, and instead of expanding the market and helping people develop and get free, the State is actually going the other way; it is basically working with the corporates. Take the example of the farm bills. They actually are likely to create space for the corporate interests to benefit from the vagaries of weather and crop patterns. They’ll obviously buy all products at much cheaper rates because there’s no support price. So all these vulnerable sections need to be supported by the State, and the State is the only agency that can do it; no one else will do it. This would actually benefit everyone, including the larger market economy.

This is where aspiration becomes very important. Aspiration, in some sense, motivates you to work harder. Many of these young people who became global entrepreneurs are kids of school teachers and low-level government employees. They did not grow up with riches, and now their starting salaries are more than the salaries of their fathers at the time of their retirement. They are successful because they’re willing to work hard. That is the aspirational revolution, and it’s something we are losing out on – our demographic dividend. We can only benefit from this only by expanding our economy. Our most valuable resource is our population. They need to be cultivated. So you need to invest much more in education, in health and other infrastructure which would benefit everyone.