I went through a strange crisis this year. It wasn’t directly related to the health scare amidst the pandemic or the subsequent economic uncertainty. It was a little more managerial – a crisis of organising the sudden excess of time on my hands. Not that I was able to complete all my tasks with surplus to spare; my list of chores remained as unending as ever. The problem was that all time – whether surplus or not – seemed the same. Irrespective of what filled my day, my physical interactions were restricted to the same walls, the same furniture, the same space and the same people. With little external activity and stimulus, I began to inescapably obsess over where our lives were headed – what would the near future look like? How would we get there? And what would we do once we arrived?

To figure these questions out, I decided to do what this age allows us to do best – reach out to random people on the internet and gather their insights. I designed a survey to understand how people were adapting to this time, and whether or not their ideas about life, work, their dreams and their plans to achieve them had changed, and invited friends and strangers online to share their responses.

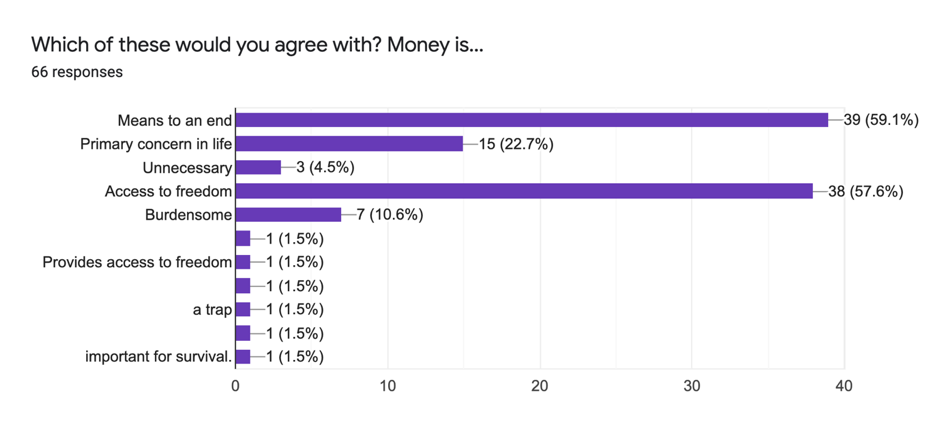

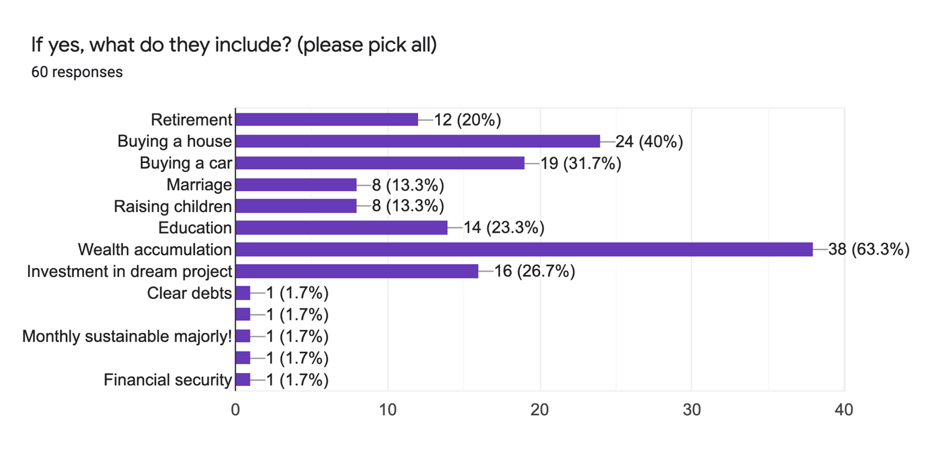

In one section of the survey, I inquired about their relationship with the concept of money: what did money mean to the respondents? The most popular answers: “means to an end” and “access to freedom.” In another section, I asked what this end was – what was it that people were so diligently saving all this money for? The popular answer, by a margin: “Wealth accumulation.”

I was intrigued and amused by these responses. Not only did the end turn out to be money itself, but most likely, the respondents hadn’t even noticed this to be the case! The accumulation of wealth for its own sake, in this survey, overtook goals like investing in your dream project, ensuring funds for education or even the conventionally popular option of pursuing a comfortable retirement. Perhaps the belief was that once wealth is accumulated, any of these options can be made available. Money was indeed the means to an end, just an end that was yet undefined.

Even so, there remained a fly in my soup. Despite listing many options, why did the most popular answer evoke a lack of clarity about these goals? Was it a problem of excessive choice, a lax or uncertainty about the future (especially given our current circumstances), or was it something deeper that reflected our psyche in this hyper-active capitalistic world? As I thought about this, I realised the key to answering these questions lay in better understanding one of the most common yet misunderstood resources – time.

The comfort with ambiguity that is apparent in these responses comes, perhaps, from a definitive faith or trust in an imagined future – one where we have accumulated enough wealth to think about what we want to do with it. This ‘future’ time is characterised by all our hopes and dreams; perceived as a resource available in infinite quantities. The present, on the other hand, is seen as being more limited; one which needs to be constantly invested in productive activities in order arrive at the promised future. But does this future always arrive?

Social anthropologist Kostas Retsikas argues that empirically, we never really experience a drastically different future. Instead, we keep returning to a slightly different present. In his 2015 study on welfare programmes in Indonesia, he observed that the incremental monetary benefits that the poor reap through various mechanism of microfinance fuel the belief that enough cycles of credit and debt can eventually bring them out of poverty. “The capacity [of the poor] to honour [loan] obligations is itself held as capable of extending obligations into infinity: the chance of acquiring a higher value loan in each new round of credit/debt circulation is deemed as absolutely necessary for creating enough ‘lift’ to elevate the poor out of poverty, transposing them to prosperity,” he observes. “Nevertheless, achieving such incremental ‘lift’ requires the unending return of value as credit/debt.” The mark-up that these organisations receive in loan repayments are further made available as higher loans, which would carry even higher mark-ups, and so the cycle of credit and debt goes.

As a result of this process “the time the poor have at their disposal acquires meaning through the pursuit of money.” In this meaning-making exercise, an unwitting hierarchy of activities is created. “These instruments obliterate everything creative that cannot be turned into something productive and suppress everything energetic that cannot be made into something advantageous,” claims Retsikas. “This obliteration is the horror that lies at the heart of promises of progress and development.”

These observations apply not just to poverty-reduction programmes but, through the capitalist logic, to all our lives. Without an end in mind, the accumulation of money becomes an infinite quest for us all. More often than not, the more money we have (or even somebody else has), the more we want. This is not a fault in the market’s logic of time and labour. Internally, this logic makes sense. The fallacy lies in assuming that the logic of the market applies across all sectors of our life – personal, social, psychological and political.

It is this very logic that turns the surplus time on my hands into a crisis rather than a boon. With the logic of the market deeply ingrained into my mind, the never-ending list of tasks haunts me even after a long, productive day. “What if I don’t get a chance to finish this item on my list again?” remains a constant question on my mind, even when I’m trying to unwind. Sometimes, I give in. It helps me control the urge to procrastinate. Other times, when the pause is not one of avoidance, this backfires, landing me in a fit of anxiety and self-doubt.

Time starts to be measured not by the manner in which it is spent, but the output it produces – much like the way labour is evaluated in the market. Any moment one doesn’t spend creating something or being productive in every way imaginable is considered a waste. The mere fact of having time on our hands brings with it the burden of spending it the ‘right way’.

The irony here is that there may not be a universal ‘right way’. There are enough neurological and psychological studies to show that the needs of each individual vary greatly from one another on matters of physiology, psychology and society. Everything from how much time we spend with people, to how much time we spend sleeping impacts our energy levels and the way we are able to go about our day and take on (ad)ventures of varying degrees. The needs, as the oeuvre, of each individual can present a multitude of possibilities — possibilities that are currently curbed by the obscure logic of time in our socio-economic bubble.

Outside of structurally changing the way we design engagement in this age, I’ve realised the only way out of this cycle is to reclaim our own time – the time I spend all by myself; the time that feels not necessarily productive, but enriching; a time driven by me and not the market. At least this way I am able to add that incremental difference of experience and perspective in life, which can accumulate to become much more beneficial in the longer run.