It was the winter of 2016. I had just stepped out of a tutorial session at my University in London, when some of my fellow students approached me rather excitedly. There was a palpable sense of purpose among all the Indian students that afternoon.

“Are you coming?” one of them asked me.

“Where?” I responded.

“To the protest, of course!”

As it turned out, some students and academics from London School of Economics, King’s College, School of Oriental and African Studies, Birkbeck, Cambridge University, Portsmouth and Southampton had organised a gathering outside the India House near my University in solidarity with the students of Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). The participants were protesting the arrest of three JNU students who had allegedly raised and instigated “anti-India” slogans at a gathering on their campus. The organisers of this protest were standing for the right to free speech, especially in a diverse democracy like India.

I had only attended one other protest before this, though my attempt to join it had failed miserably. In February 2011, a solidarity march had been organised in Delhi to demand justice for Arushi Talwar, a teenage girl who was found murdered inside her house under mysterious circumstances. We arrived at the protest venue a little later than the reporting time, but managed to join a group of people walking along the designated path. As we began to walk with them, however, we noticed an overwhelming presence of the colour saffron – on people’s clothes; flags; handkerchiefs; banners. It didn’t take us long to realise we had unwittingly joined a right-wing religious procession, and immediately uprooted ourselves from the venue. We tried to hide our embarrassment behind the fact that Jantar Mantar is a hub of protests in Delhi, and reasoned that it would certainly be easy to get lost amongst the various causes being raised here. By then, we had lost all hope to join the correct movement and carried on with our day instead.

I saw the opportunity I was presented with in London as a way to redeem myself from this experience. So, when my fellow Indian students asked if I was going to join the protest that rare sunny afternoon, I agreed. I didn’t know what we would achieve by gathering many miles away from the controversy, but it seemed important to show solidarity – it was (quite literally) the least we could do.

By the time we reached the venue, the protest had already gathered some momentum. Some people were distributing placards; others were documenting the gathering through pictures and videos; a couple of leaders were passing a megaphone between them and shouting slogans that others were religiously repeating. Even though I had joined the correct protest this time, I still felt uncomfortable in its midst. There was a strong sense of agitation among the crowd, which, I thought, gave an ugly nature to an otherwise well-meaning gathering. To demonstrate, one of the slogans that caught on with the crowd was “Narendra Modi, murdabad,” the literal meaning of which is “Death to Narendra Modi”, though it can also be translated as “Down with Narendra Modi.” I stopped repeating the slogans after this. The protest ended in an hour or two, and everyone dispersed to carry on with their day.

This experience, however, left a deeper mark on my mind than the previous one. It made me reflect on the language of protest as is practiced so often today. What is the language we use when we engage in acts of protest? What is the best way to express dissent or demand rights? Can gathering in protest be effective in anything more than generating solidarity? How can the act of protest be taken forward to make it truly and effectively subversive?

James Scott, one of the most notable contemporary anthropologist and political scientist to study the “weapons of the weak” – tools used by minority and suppressed groups to navigate through the hegemony – stated in his book ‘Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts’ (1990):

“That first declaration speaks for countless others, it shouts what has historically had to be whispered, controlled, choked back, stifled, and suppressed. If the results seem like moments of madness, if the politics they engender is tumultuous, frenetic, delirious, and occasionally violent, that is perhaps because the powerless are so rarely on the public stage and have so much to say and do when they finally arrive.”

The aggression that comes out in such cases, though not practiced or encouraged as a sustainable model of protest, is justified. The aggression here is not rhetorical but sincere, and therefore effective in building empathy amongst its audience and participants. The violent language used by the protestors we discussed earlier, however, hardly comes from those who have historically had to whisper. Their anger stems from a collective feeling of injustice, and is a vicarious reaction, not a considered, thought-out response.

To what degree is such hyperbolic anger effective? Or, could it be that this misplaced emotion actually becomes counter-productive?

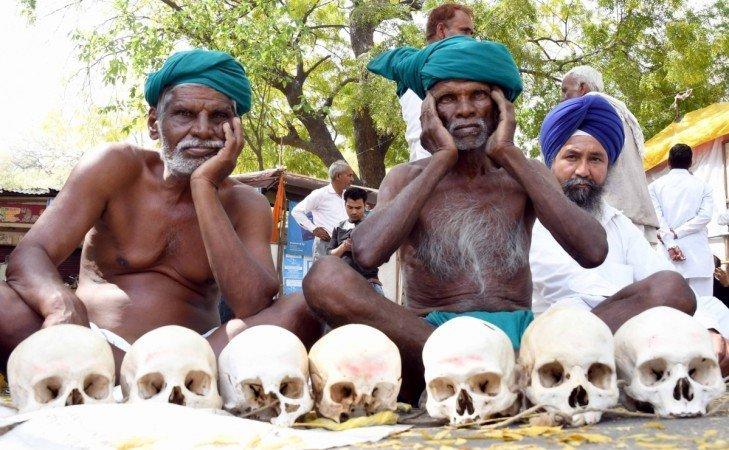

The News Minute, earlier this year, carried an interesting comparative analysis of the protests carried out in New Delhi by farmers from Tamil Nadu and in Mumbai by the farmers from Maharashtra. The report suggested that one of the reasons for the failure of the former protest, and unprecedented success1 of the latter, was the language used. The farmers from Tamil Nadu used a lot of paraphernalia – such as skull and bones of farmers who had died due to adverse conditions, and running naked in front of the Prime Minister’s residence – in their protest. These visuals seemed to take the focus away from the actual message, and onto the aesthetics used to convey it. This form of protest also projected an off-putting hostility on the movement, which, though justified, became counter-productive to inviting support from empathisers. Their language was one of anger and blame, deeply founded in the suffering they had been through, and the threats that remained. The negativity that this language carried, in a way, restricted the possibility of productive engagement, and hence, resolution. This is not to say that the protesters did not want to resolve their issues – that would be a mindless suggestion – but their language of pain, suffering and blame seemed to have overshadowed their call for help.

On the other hand, the protest in Maharashtra, while having an advantage of numbers and home ground, was also peaceful, disciplined and compassionate. Even as there was a strong, assertive quality to the demands being made, which were also based on the pain and suffering of the farmers, the protest itself managed to remain free of the baggage and heaviness that their counterparts carried through their histrionics. In addition, the protestors tried to contain the trouble caused to the residents of the city as much as possible, which resulted in them gaining the support of even the city-dwellers, who were otherwise unaffected by their cause. I think this was the most significant victory of this protest.

This victory was made possible because of an intense connection to the space and time of protest. Without getting consumed completely by their own troubles and problems the protesters in Maharashtra marched to Azad Maidan a night before an important Board exam scheduled for school students in the city, to clear the routes and ensure a hassle free morning for the examinees. Despite their difficult circumstances and agonising journey ahead, the protesters were considerate in their actions, which won the hearts of the locals, and opened up their cause to the ‘others’.

India’s struggle for independence also holds a bank of lessons for effectively expressing dissent. Like in the case of the farmer protests, it was the direct voice and numbers of the oppressed that carried the impact. In contrast to middlemen and activists becoming the voice of the oppressed in a vicarious way, which is what we see as a common practice today, directly hearing the stories, concerns and demands of the affected makes these movements more organic and hence truthful. This is not to say that other groups and organisations shouldn’t associate with such movements – in fact the protest in Maharashtra was joined and supported by many urban and rural intellectuals who contributed to its success by providing diverse insights – but passing the microphone (or megaphone, if that is the preferred instrument of amplifying the movement’s voice) will do good by creating a more open and empathetic space of dialogue and action.

A wonderful reference point for this methodology is the work done by KHOJ, an international artists’ association based in New Delhi that undertakes collaborative art and cultural projects with refugees, migrants and locals living in surrounding areas. Through interactive public events – that involve delicious food, interesting stories and beautiful public art – KHOJ provides a platform for collaborators to showcase their rich culture, and invite others to engage with it. Such practices are a creative way to protest and counter the racism and exclusion that these migrants and refugees often face. They subvert the basis for discrimination itself to build empathy in this multicultural space.

A similar strategy was also employed by Gandhi in his arguments for freedom from colonial domination – using the Bible to evoke the idea of equality and subvert the notion of the ‘white man’s burden.’ 2

Introducing such subversive and novel ideas, however, requires a careful and considerate use of language. It is easy to get lost in jargons and categories that are so casually and irresponsibly thrown around during these protests. Words like ‘capitalist’, ‘communist’, ‘liberal’, ‘conservative’ are used without a deep understanding of their history and context, to brand individuals and ideas as so distant from your own, that they are coloured untrustworthy and/or ludicrous. If the premise of an argument itself is the complete and total rejection of a school of thought, there remains no scope to engage in discussion, break down differing ideas, and co-create a unique and contextualised solution.

Right after the protest in London, some of us had gathered at a coffee shop close-by to recuperate from the exhaustion of standing and shouting for hours. When I raised concern about using words such as murdabad in a peaceful protest, some of the left-wing ideologues were appalled to hear my reasons. They could not believe that someone would think that any idea other than that of the left was worth even listening to, forget protecting. It was only after a long discussion, that they were able to at least consider my position, if not accept it.

There have and always will be merits and limitations to ideas and theories, which are further subject to the context of their creation and their usage. A nuanced discussion of these ideas, which is relevant to the current times, and does not blindly accept or reject ideas based on these constructed categories, will always be the most effective way of communication. Who wants to listen to or engage with someone that only complains and outright rejects opposing views?

Unfortunately, this last suggestion, though seemingly intuitive, is the most overlooked strategy in protests. It is understandable that emotions often run high when faced with the kind of atrocities and injustices we see today. It is also easy to get lost in the anger and hurt that one feels when encountering these atrocities and their stories. However, like Scott mentioned earlier, it is only the first declaration that, on account of coming after years of oppression, is justifiably aggressive (and maybe even effective). All subsequent bawling only adds to and gets lost in the noise already pervading our lives. If we truly want to address issues concerning our times, we need to elevate from the shrieks and evolve a language that can initiate an interaction between people holding differing views.

1 There have been many debates and discussions about the merits of the relief provided to the farmers. The unprecedented success referred to here is the sheer attention and direct dialogue with the government that this protest initiated.

2 A detailed account of this is available in Apoorvanand’s article in the Basic Conversations section of this issue.